Margaret Helen Anderson Greville

Greville [née Anderson], Dame Margaret Helen (1863–1942), society hostess, had a difficult early life. She was born in London on 20 December 1863. Her mother, Helen (1835/6–1906), had married William Anderson, day porter at the Edinburgh brewery of William M'Ewan [see McEwan, William (1827–1913)]. M'Ewan supposedly put Anderson on night duty to facilitate his own access to Mrs Anderson, who was a cook. After the porter's death M'Ewan in 1885 married Helen Anderson and adopted her daughter, who was his presumptive only child. He was a plain, blunt man, and a domineering but indulgent father.

On 25 April 1891 Margaret Anderson married the Hon. Ronald Henry Fulke Greville (1864–1908), elder son and heir of the second Baron Greville. He was a suave and genial captain in the Life Guards, but she so disliked army society that after a few years she threatened to leave him unless he sent in his papers to enable her to launch her social career in London. Her husband complied, and became a reputable if unexciting Unionist free-trader MP for East Bradford (1896–1906). Their marriage was her grappling hook onto society, where her father's money and her own persistence secured her a permanent place. After 1901 she was one of the pretty young hostesses who entertained Edward VII. Her energetic worldliness proved well attuned to the temper of the court. ‘I don't follow people to their bedrooms,’ she told the marquess of Carisbrooke, ‘it's what they do outside them that is important’ (Chips, ed. James, 336). Her success with the old king provoked resentment: the diversions provided for him by Lord and Lady Savile at Rufford Abbey and by the Grevilles at Reigate Priory earned them the sobriquet of the Civils and Grovels.

M'Ewan in 1906 bought for the Grevilles the Surrey estate of Polesden Lacey. The original Grecian villa built under the supervision of Thomas Cubitt in 1824 had recently been extended by Ambrose Poynter for Sir Clinton Dawkins. Its interior was sumptuously refitted for the Grevilles by Charles Frédéric Mewès and Arthur Davis, the architects of the Ritz Hotel, in a manner reviving the Windsor Castle style of the 1820s. Polesden Lacey is a consummate display of Edwardian opulence and eclecticism: the woodwork in the hall was made from the altarpiece of a Wren church in the City of London; ‘the Drawing Room is a sumptuous mock-Louis-Quatorze confection in white, gold and red with wall mirrors, ornate pilasters, imported French Rococo fireplaces and Italian ceiling paintings’ (Pevsner, 415). Maggie Greville inherited some good English pictures, and bought others herself. Although only 22 miles from London, the house was surrounded by sylvan gardens and commanded glorious views over the Dorking valley. Polesden Lacey's parvenu luxuries and spacious seclusion were mistaken for aristocratic elegance by middle-class politicians such as Sir Robert Horne.

The premature death of Ronnie Greville from throat cancer in 1908 required little adjustment in his widow's life. Early in her widowhood Maggie declined a proposal from Sir Evelyn Ruggles-Brise, and after hesitation she decided not to marry Sir John Simon in 1917. By the death of her father in 1913 she inherited an estimated £1.5 million including two-thirds of the voting shares in William McEwan's brewery, a private company which merged with William Younger to form Scottish Breweries Ltd in 1931. McEwan board meetings were held at Polesden Lacey, where she treated the directors with such autocratic harshness that they would leave her room trembling. She had a highly materialistic outlook, and was implacable in her pursuit of material gain. She also inherited M'Ewan's Mayfair home, which formerly had been the town house of the earls of Craven. Its upstairs drawing-room floor was fitted with priceless Louis XIV boiserie producing an effect ‘of great beauty, very perfect in taste’ (Repington, 2.482).

Maggie Greville was first cousin to George Younger and Robert Younger, who were both raised to the peerage in 1923, and as a rich brewer was herself created DBE during the former's chairmanship of the Unionist Party (1922). ‘Appropriately she looked a rather blousy old barmaid’, according to Sir Oswald Mosley (Mosley, 79). Kenneth Clark characterized her guests as ‘stuffy members of the government and their mem-sahib wives, ambassadors and royalty’ (Clark, 269). She shunned bohemians, and admitted only the most plutocratic Americans to her salon. Though Edward VIII ostracized her as a bore, her appetite for royalty remained insatiable. ‘One uses up so many red carpets in a season’, she declared (Pearson, 134); another boast was that in the course of one morning three kings sat on her bed. During a visit to India as the guest of the marquess of Reading in 1922 she chaperoned Edwina Ashley, who accepted a proposal from Lord Louis Mountbatten in Greville's sitting room in the viceregal lodge. The future George VI spent part of his honeymoon at Polesden Lacey in 1923.

In addition to cultivating monarchs Maggie Greville was assiduous in entertaining foreign ambassadors. This brought her one innocuous advantage: red carpets and special trains during her inveterate travels. There was a less innocent consequence of her attentions to diplomatists. Harold Nicolson complained in 1939:

The harm which these silly selfish hostesses do is really immense. ... They convey to foreign envoys the impression that policy is decided in their own drawing-rooms ... They dine and wine our younger politicians and they create an atmosphere of authority and responsibility and grandeur, whereas the whole thing is a mere flatulence. (Nicolson, 396–7)

After she had decried Churchill in 1942, the diplomat Charles Ritchie similarly deplored her ‘trivial but not harmless gossip’ (Ritchie, 145). Her waspishness was such that Lady Leslie exclaimed, ‘Maggie Greville! I would sooner have an open sewer in my drawing-room’ (Lees-Milne, 1.109). The earl of Crawford described her in 1933: ‘Full of stories, and if with a spice of scandal so much the better; very anti-semitic—a real good sort; but I should love to see her in a temper’ (Vincent, 551). ‘There is no one on earth quite so skilfully malicious as old Maggie’, Henry Channon wrote approvingly in 1939, ‘she was vituperative about almost everyone’ (Chips, ed. James, 208). Loyal in her friendships, she was unforgiving to her enemies, especially her rival Emerald Cunard. ‘You mustn't think that I dislike little Lady Cunard, I'm always telling Queen Mary she isn't as bad as she's painted,’ she catted to Carisbrooke (Chips, ed. James, 336). She found Hitler charming and Mussolini pompous.

During the blitz Greville shut her Mayfair house and lived mainly in Claridges and the Dorchester hotels. After a long period of disablement, during which she continued to entertain gamely, she died on 15 September 1942, at the Dorchester Hotel, and was buried on 18 September outside the walled rose garden at Polesden Lacey. In her will (for which the executors included lords Ilchester, Bruntisfield, and Dundonald) she left Marie Antoinette's necklace to Queen Elizabeth, £25,000 to the queen of Spain, £20,000 to Princess Margaret, and £10,000 to Osbert Sitwell. Polesden Lacey was bequeathed to the National Trust.

‘She was so shrewd, so kind and so amusingly unkind, so sharp, such fun, so naughty’, wrote Queen Elizabeth after Greville's death, ‘altogether a real person, a character, utterly Mrs Ronald Greville’ (Bradford, 111). Sir Cecil Beaton was less enamoured: ‘Mrs Ronnie Greville was a galumphing, greedy, snobbish old toad who watered at her chops at the sight of royalty ... and did nothing for anybody except the rich’ (Buckle, 215–16).

Richard Davenport-Hines

Sources

K. Clark, Another part of the wood (1974) · C. Ritchie, The siren years (1974) · S. Bradford, King George VI (1989) · J. Lees-Milne, Ancestral voices (1975) · C. À Court Repington, The First World War, 2 vols. (1920) · H. Nicolson, Diaries and letters, ed. N. Nicolson, 1 (1966) · ‘Chips’: the diaries of Sir Henry Channon, ed. R. R. James (1967) · R. Buckle, ed., Self-portrait with friends: selected diaries of Cecil Beaton (1979) · J. Pearson, Façades: Edith, Osbert and Sacheverell Sitwell (1978) · The Crawford papers: the journals of David Lindsay, twenty-seventh earl of Crawford ... 1892–1940, ed. J. Vincent (1984) · R. Feddon, ‘Polesden Lacey, Surrey I’, Country Life, 103 (1948), 478–81 · R. Feddon, ‘Polesden Lacey, Surrey II’, Country Life, 103 (1948), 526–9 · O. Mosley, My life (1968) · B. Nichols, All I could never be (1949) · S. Keppel, Edwardian daughter (1958) · Surrey, Pevsner (1971) · earl of Portsmouth, A knot of roots (1965) · m. cert. · d. cert. · B. Masters, Great hostesses (1982) · P. Ziegler, Osbert Sitwell: a biography (1998) · National Trust, Polesden Lacey (1999), 56 · The Times (4 Sept 1906), 1a · The Times (19 Sept 1942)

Likenesses

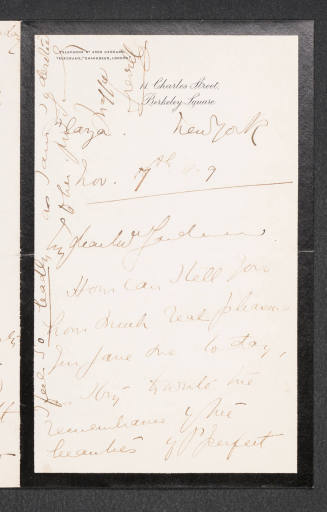

E. A. Carolus-Duran, oils, 1891, Polesden Lacey, Surrey [see illus.] · H. Schmiechen, oils, 1899, Polesden Lacey, Surrey

Wealth at death

£1,623,191 17s. 0d.: resworn probate, 5 Jan 1943, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Richard Davenport-Hines, ‘Greville , Dame Margaret Helen (1863–1942)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2006 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2113/view/article/51986, accessed 8 Aug 2013]

Dame Margaret Helen Greville (1863–1942): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/51986

[Previous version of this biography available here: September 2004]