Malvina Hoffman

Hoffman, Malvina (15 June 1885-10 July 1966), sculptor, was born Malvina Cornell Hoffman in New York City, the daughter of Richard Hoffman, a pianist, and Fidelia Marshall Lamson. Her early years were spent in a handsome brownstone on West 43d Street in New York City. Her father, born in England, was an internationally recognized pianist who first came to the United States as an accompanist to Jenny Lind, the Swedish soprano. Richard Hoffman's home was filled with works of art and artists, inspiring his daughter's interest in art.

Hoffman attended classes at the Woman's School of Applied Design and the Art Students League while still in her teens. She studied painting privately with John White Alexander. In 1906 she began to study sculpture with Herbert Adams and George Grey Barnard at the Veltin School. The young artist received private instruction in sculpture with Gutzon Borglum before traveling to Paris in 1910. That summer Hoffman worked as an assistant in the Parisian studio of American sculptor Janet Scudder. For the following two years she also benefited from critiques by Auguste Rodin. In 1911 she completed her first figure group, Russian Dancers (Detroit Institute of Arts), which was based on Anna Pavlova and Mikhail Mordkin, whom Hoffman saw in a London performance the previous year.

Hoffman spent the winters of 1911 through 1913 in New York City, attending anatomy classes at Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons. In order to overcome the prejudices against women artists, she developed superb technical skills and produced many anatomical drawings. In 1914--until the fall, when she returned to the United States--Hoffman resided in Paris, where she met Gertrude Stein, Henri Matisse, Romaine Brooks, Frederick MacMonnies, Mabel Dodge (Mabel Dodge Luhan), and Constantin Brancusi. Her study with Rodin developed into a lasting friendship, and he was a dominant influence on her early work. She also became acquainted with dancers Anna Pavlova and Vaslav Nijinsky, who were to inspire many sculptures of dancing figures. In 1924 Hoffman's polychrome portrait mask of Pavlova (1924; Metropolitan Museum of Art) won the Watrous Gold Medal of the National Academy of Design.

Dance was a major theme in the oeuvre of Hoffman. Her inspiration stemmed principally from Anna Pavlova, whom she first saw perform with Sergei Diaghilev's Ballet Russe in 1910. The bronze group Bacchanale Russe (1912; Metropolitan Museum of Art) depicts Anna Pavlova and Mikhail Mordkin in the opening moments of "The Bacchanale," a dance choreographed by Michel Fokine. Energy emanates from this sculpture, which depicts both dancers raising their arms to grasp a billowing drapery as they begin their pas de deux. Hoffman captured brilliantly a single moment in the dance. When she modeled this sculptural group, Hoffman acknowledged her study with Rodin, who inspired her interest in depicting figures in motion. She presented a more realistic likeness of her subject than did Rodin, but the attention to movement and the attempt to capture a fleeting moment can be compared to the French master's depictions of dancers. In 1917 the Bacchanale Russe was exhibited at the National Academy of Design and won the Shaw Memorial Prize. It was enlarged to a "heroic-size bronze" and acquired by the French government for the Luxembourg Gardens in 1918--the only work by a woman in either the garden or the interior galleries of the Luxembourg Museum. The sculpture was seized by the Nazis in 1941.

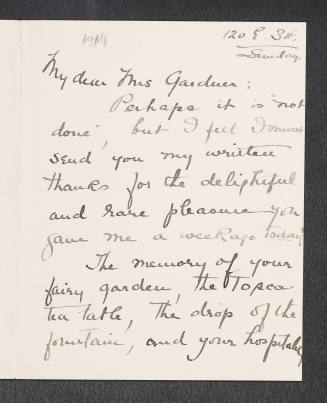

Hoffman made studies of Anna Pavlova as early as 1910, but she did not meet the famous Russian ballerina until 1914. The two women became close friends, and Hoffman made hundreds of sketches of the dancer. In addition to many studies of Pavlova with her partners, Hoffman also represented the dancer in a solo role. Pavlova Gavotte (1915; Metropolitan Museum of Art) is a fluid and sensitive depiction of a trained body in motion. Hoffman's technical proficiency allowed her to capture a realistic likeness of the gesture and movement of the renowned dancer. In her autobiography Hoffman recalled Pavlova's posing for this sculpture in her small studio on Thirty-fourth Street in Manhattan: "Once inside the studio she would disrobe and reappear 'in costume,' as she insisted on calling it . . . a snug little suggestion of short tights, long-heeled golden slippers, and the famous yellow poke bonnet with long streamers. . . . The diaphanous clinging yellow satin dress, which I added as drapery after the nude figure was completed, served to accentuate the grace and rhythmic silhouette of her figure" (p. 144).

In June 1924 Hoffman married Samuel B. Grimson but continued to use her own name professionally. They were divorced in 1936; they had no children. Active as a sculptor for more than forty years, Hoffman produced fountains, statuettes, and architectural sculpture. She was renowned for her portrait studies. Among her portraits are those of Ivan Mestrovic, Katharine Cornell, and Ignace Paderewski.

Hoffman's proficient naturalism and her penetrating study of character found its best expression in a major commission from the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago: studies of the ethnic groups of the world. A series of figures, referred to as the "Living Races of Man," was to be displayed in the Hall of Man in the Field Museum. With her husband, Hoffman traveled around the world in 1931 and 1932, gathering information for her commission. By 1933 she had cast 102 original bronzes and had created other full-length figures and sculptural groups related to the Field Museum bronzes. Examples of Hoffman's ethnographic works were exhibited in a number of American cities following the acclaim she received for her remarkable commission.

When the Hall of Man opened at the Field Museum in 1933, about eighty of her sculptures were exhibited; by 1935 all of them were on display. In her world travels, Hoffman had been assisted by anthropologists who found "pure" ethnic types to be her models. The sculptor tried to create likenesses that exemplified the diverse races, but she always considered her assignment "art" rather than "anthropology." Her ethnographic portraits lack much of the spontaneity and suggestion of character that viewers sense more readily in Hoffman's busts of her friends.

Ni-Polog (1931; Metropolitan Museum of Art), a portrait of a Balinese temple dancer, is a small study (one-third of life-size) related to her life-size portrait for the Races of Man series in the Field Museum. The sculpture features variations in the patination to emphasize the black hair contrasting with the warm brown flesh. In her book Heads and Tales (1936) Hoffman mentioned her trip to Bali and her completion of a head of Ni Polog, who is shown in a photograph (p. 258). While in Bali, Hoffman also worked on a full-length statuette of the same Balinese dancer in elegant regalia.

Hoffman mastered marble carving, plaster casting, and the building of armatures. She experimented with lost-wax casting in her own studio and wrote a book about sculpture techniques. She was elected to membership in the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1937 and was made a fellow of the National Sculpture Society. In 1939 Hoffman exhibited a sixteen-foot relief of dancing figures at the New York World's Fair. After 1940 she continued to make portraits. In 1948 she was given a commission for a World War II memorial. In 1964 she was awarded the National Sculpture Society's Medal of Honor. She died of a heart attack in her studio at 157 East 35th Street in New York City.

In the latter part of the twentieth century Malvina Hoffman's sculpture has been received as competent academic work in an age identified with modernism. Her reputation has benefited from the critical attention given to women artists of the past and present.

Bibliography

Papers of Malvina Hoffman are at the Archives of History of Art, Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, Los Angeles. Her autobiography is Yesterday Is Tomorrow: A Personal History (1965). She was also the author of several books with technical information about the creation of sculpture, among which are Heads and Tales (1936) and Sculpture Inside and Out (1939). There are no monographs on Malvina Hoffman, but see Linda Nochlin, "Malvina Hoffman: A Life in Sculpture," Arts Magazine 59 (Nov. 1984): 106-10, and "Malvina Hoffman," in Janis Conner and Joel Rosenkranz, Rediscoveries in American Sculpture: Studio Works, 1893-1939 (1989).

Joan Marter

Back to the top

Citation:

Joan Marter. "Hoffman, Malvina";

http://www.anb.org/articles/17/17-00415.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 15:22:39 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.