Madge Kendal

Kendal, Dame Madge [real name Margaret Shafto Robertson; married name Margaret Shafto Grimston] (1848–1935), actress, was born on 15 March 1848 at Grimsby, Lincolnshire, the youngest of (allegedly) twenty-two children of William Robertson (d. 1872) and his wife, the actress Margharetta Elisabetta Robertson (d. 1876), née Marinus, whose parents had moved to England from their native Netherlands. Well educated and literary in his tastes, William Robertson gave up his apprenticeship with a Derby solicitor to join the family's Lincolnshire theatrical circuit, of which he became manager in the early 1830s. By then he had met and—in 1828—married Miss Marinus, who on 9 January 1829 gave birth to their first child, Thomas William Robertson, who became the founder of the naturalistic school of drama in the 1860s. In his apocryphal phrase, T. W. Robertson was ‘nursed on rose-pink and cradled in properties’, as evidently were his siblings, certainly Madge, who appeared on the stage as a babe in arms.

Early days on the stage

Madge Robertson's first known speaking part was as Marie in Edward Stirling's nautical drama The Struggle for Gold, on 20 February 1854 at the Marylebone Theatre, of which her father was then co-lessee with J. W. Wallack. Five days later she appeared as the blind Jeannie in an adaptation of Dickens's The Seven Poor Travellers, in a cast consisting largely of members of her family.

In 1855 the Robertsons repaired to Bristol, where they were engaged by J. H. Chute. As Eva in an adaptation of Uncle Tom's Cabin, Madge revealed an exceptional singing ability in her rendition of ‘I see a land of spirits bright’ and other songs, though sadly diphtheria and the removal of her tonsils prevented her voice from reaching its potential. Nevertheless, when Chute opened the new Bath Theatre in March 1863 with a production of A Midsummer Night's Dream, Madge was cast as Second Singing Fairy—‘Over hill, over dale’, ‘I know a bank’ in Mendelssohn's settings—alongside Ellen Terry as Titania and Kate Terry as Oberon. Throughout her apprenticeship in Bristol and Bath, Madge, already tall for her age, was rigorously coached by her father, who taught her the value of contrast by the repetition of Viola's tender and pathetic ‘She never told her love’ from Twelfth Night and Queen Constance's vehement ‘Gone to be married, gone to swear a peace’ from King John.

A developing reputation

Technically skilled beyond her years, Madge Robertson made her London adult début with Walter Montgomery at the Haymarket Theatre and created a favourable impression as Ophelia (29 July 1865), Blanche in King John (10 August), and Desdemona (21 August). She returned to the provinces initially with Montgomery and in 1866 for William Brough at the Theatre Royal, Hull, where Samuel Phelps had been engaged for three nights during fair week. The stock company's Lady Macbeth being unwell, Madge was thrust into the role, and met her Thane for the first time after her delivery of the letter scene, not having had the benefit of rehearsing with him. The young actress's technique stood her in good stead and Phelps subsequently invited her to appear as Lady Teazle to his Sir Peter in Sheridan's The School for Scandal at the Standard Theatre, Shoreditch. In old age Madge Kendal drew upon her youthful experience to give an imitation of Phelps as Macbeth.

After provincial and metropolitan engagements (for F. B. Chatterton at Drury Lane, E. A. Sothern at the Haymarket, and John Hollingshead at the new Gaiety Theatre) Madge Robertson joined J. B. Buckstone's company, initially on tour and thereafter at the Haymarket, where she remained until 1874. On 7 August 1869, at St Saviour's Church, Manchester, she married an actor from Buckstone's company, William Hunter Grimston, whose stage name of Kendal she adopted professionally. The couple had wrung from William Robertson his reluctant consent to their marriage on the condition, which they consistently observed, that they would always act together—in Shaw's words, ‘a Perpetual Joint’ (Dame Madge Kendal, 70).

William Hunter Kendal (1843–1917), actor and theatre manager, was born in London on 16 December 1843, the eldest son of Edward Hunter Grimston and his wife, Louisa Rider. Grimston, whose maternal grandfather was a painter, showed early talent in that art, but was intended for medicine until his regular visits to the Soho Theatre to sketch the performers led to his appearance on stage in A Life's Revenge (6 April 1861), using the stage name Kendall (he subsequently dropped the second l). Kendal remained at the Soho Theatre for two years before seeking experience in the provinces, notably Glasgow, where he remained for four years. In 1866 he joined J. B. Buckstone's company.

At the Haymarket, Madge Kendal enjoyed a string of successes, notably as Lilian Vavasour in Tom Taylor's New Men and Old Acres (25 October 1869), Lydia Languish in The Rivals (24 October 1870), Rosalind in As You Like It (9 October 1871), and Mrs Van Brugh in W. S. Gilbert's Charity (3 January 1874). Following engagements at the Opéra Comique and the Court Theatre she joined the Bancrofts at the Prince of Wales's Theatre, where her roles included Dora in Diplomacy (12 January 1878), adapted from Sardou's Dora by B. C. Stephenson and Clement Scott. Her husband having refused to play Bassanio in The Merchant of Venice, Madge Kendal—true to her father's injunction and in keeping with the spirit of the caskets—declined the Bancrofts' invitation to play Portia, thereby leaving the way clear for Ellen Terry to play the role.

A tall, very good-looking man, W. H. Kendal had a gift for light comedy but was stilted and unnatural in more serious roles. His repertory, which was almost invariably determined by the opportunities offered to his wife, included Colonel Blake, resplendent in a full-length bearskin coat, in J. Palgrave Simpson's A Scrap of Paper, Orlando, Captain Beauclerc in Diplomacy, William in William and Susan, W. G. Wills's customized rewriting of Douglas Jerrold's Black-Eyed Susan, and Aubrey Tanqueray to his wife's Paula in Pinero's The Second Mrs Tanqueray. Kendal's real skills were managerial and financial. His wife recalled that, at the end of each season during their partnership with Hare at the Court in the 1870s, Kendal invested his share of the profits, always leaving enough over for some jewellery for her and a painting for himself. With his flair for art Kendal assembled a fine collection of contemporary paintings, which was housed in their increasingly grand dwellings—Taviton Street, Harley Street, and Portland Place, plus The Lodge, Filey, Yorkshire. Madge Kendal gave Hugh Walpole's portrait of her husband to the Garrick Club, of which he had been a member (he was also a member of the Junior Carlton, Beefsteak, Arts, Cosmopolitan, and AA clubs).

From 1879 to 1888 the Kendals shared the management of the St James's Theatre with John Hare, with whom Kendal had previously entered into a ‘silent’ partnership at the Court Theatre. At the St James's, Madge Kendal's successes included Lady Giovanna in Tennyson's The Falcon (18 December 1879), Susan in William and Susan, Kate Verity in Pinero's The Squire (29 December 1881), and a reprise as Rosalind (24 January 1885). Her Rosalind had always been noted for her vivacity, irony, and pathos rather than her tenderness and lyricism, but with advancing years impulse, spirit, and spontaneity had fallen victims to calculated points of business and over-deliberate delivery of speeches. Of Madge Kendal's acting at this time, W. E. Henley wrote: ‘How carefully she constructs a part, and how consummately she executes! Voice, face, presence, habit, disposition—everything is turned to account’ (The Stage, 17 April 1886).

A national figure

By the mid-1880s the Kendals were benefiting from the improvements in the status of the theatre to which they had significantly contributed. In Society in London (1885, 295), T. H. S. Escott wrote: ‘Mrs Kendal, one of the best artists of her sex on the London stage, is in private life the epitome of all domestic virtues and graces.’ W. H. Kendal epitomized the gentrified theatre of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century; of him Herbert Beerbohm Tree said, ‘when I look at Kendal I know acting is the profession of a gentleman’ (Dame Madge Kendal, 30). On 23 September 1884 Madge Kendal addressed the Congress of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science in Birmingham with a paper entitled ‘The drama’, in which she robustly proclaimed the advances in her profession, though she made some barbed allusions to certain fairly easily identifiable members of it of whom she disapproved. In 1886, like much of fashionable London, the Bancrofts interested themselves in the case of John Merrick, the Elephant Man, as a consequence of which Madge Kendal herself eventually achieved the status of a dramatic character, in Bernard Pomerance's 1979 play and the subsequent film. In February 1887 the Kendals were commanded to perform before the queen and court at Osborne, the first such entertainment since the prince consort's death. The queen sent Mrs Kendal a diamond brooch as an expression of her appreciation, and the actress received a similar token of esteem from Joseph Chamberlain at a farewell banquet on 16 July 1889, before an American tour. The Kendals spent most of the next five years in the United States, very much to their financial advantage.

When Madge Kendal returned to the London stage in the 1890s her accomplishments were relished by Shaw, who wrote in the Saturday Review of her performance in Sydney Grundy's The Greatest of These at the Garrick Theatre (10 June 1896): ‘her finish of execution, her individuality and charm of style, her appetisingly witty conception of her effects, her mastery of her art and of herself ... are all there, making her still supreme among English actresses in high comedy’ (Shaw, 2.157). This supremacy was put to the test when Herbert Beerbohm Tree invited Madge Kendal and Ellen Terry to appear together in The Merry Wives of Windsor, as Mistress Ford and Mistress Page respectively, at His Majesty's Theatre in 1902. Tree allegedly observed the on-stage reunion of the two actresses, hidden in a box. Madge Kendal always proclaimed the mutual affection between the two women from their teenage years in Bath, but her saccharine recollection of ‘Nellie’ buying apples and generously sharing them with ‘Madge’ turns sour when she describes Ellen Terry as ‘a real daughter of Eve’ (Dame Madge Kendal, 26). In the event, as Mistress Ford Madge Kendal shed some of her customary artifice and displayed an unwonted exuberance and apparent spontaneity, though whether this was in any way connected with the fact that for the only time since her marriage she was performing without her husband can only be a matter of speculation. The Kendals renewed their professional partnership for the remaining years of their careers until they retired from the stage in 1908, though Madge did return—as Mistress Ford—for the coronation gala of 1911.

Family life, retirement, and death

Though they were such a devoted couple, the Kendals' family life was deeply troubled, and in her memoirs Madge recurrently refers to herself as ‘Mater Afflicta’. The Kendals—or the Grimstons as they were always known in family and social life—became estranged from their four surviving children; William observed at the grave of their first-born, Margaret: ‘All the children that loved us, Madge, lie under this stone’ (Dame Madge Kendal, 85). Madge Kendal attributed her husband's death on 6 November 1917 to a broken heart and wounded pride caused by their children's behaviour, in particular the divorce of their youngest daughter, Dorothy, in 1913 from the manager Bertie A. Meyer. During her lengthy retirement and widowhood Madge Kendal, always resolutely Victorian in her appearance and opinions, maintained a public presence. She supported the Actors' Association, the Royal General Theatrical Fund, the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, and Denville Hall, the actors' retirement home, of which she became president. In 1926 she was appointed DBE and in 1927 GBE; for her eightieth birthday she sat for a portrait by Sir William Orpen and recorded a speech from As You Like It for the BBC; in 1932 she became the first woman to receive the freedom of Grimsby, which, after a lifetime's uncertainty, had been established as her birthplace; and in 1933 she published her memoirs, Dame Madge Kendal by Herself, written with the assistance of Rudolf de Cordova.

Dame Madge Kendal died at her home, Dell Cottage, Chorleywood, Hertfordshire, on 14 September 1935. By her own wish only her doctor and a nurse were present at her bedside, and her funeral—at St Marylebone cemetery, East Finchley—was private. The obituary in The Times (16 September 1935) spoke of Dame Madge's ‘very unhistrionic coldness of temperament and ... superficiality of thought’ as ‘the barriers between her acting and any form of greatness’. The actress and the woman are inseparable, and these characteristics also formed a barrier between Madge Kendal and her children, as a consequence of which, her closing years, her death, and her funeral were acted out in isolation from her family. Intentional or not, the ambiguity in the title of Madge Kendal's memoirs was sadly apt.

Richard Foulkes

Sources

Dame Madge Kendal by herself, ed. R. de Cordova (1933) · T. E. Pemberton, The Kendals: a biography (1900) · C. E. Pascoe, ed., The dramatic list, 2nd edn (1880) · J. Parker, ed., Who’s who in the theatre, 5th edn (1925) · B. Hunt, ed., The green room book, or, Who's who on the stage (1906) · The Era (1865–1935) · The Stage (1880–1935) · The Times (16 Sept 1935) · B. Duncan, The St James's Theatre: its strange and complete history, 1835–1957 (1964) · J. Gielgud, J. Miller, and J. Powell, An actor and his time, rev. edn (1981) · S. Hicks, Me and my missus (1939) · J. Gielgud, The Times (28 Jan 1978) · G. B. Shaw, Our theatres in the nineties, rev. edn, 3 vols. (1932) · M. Kendal, Dramatic opinions (1890) · B. Pomerance, The elephant man (1979)

Archives

V&A, theatre collections

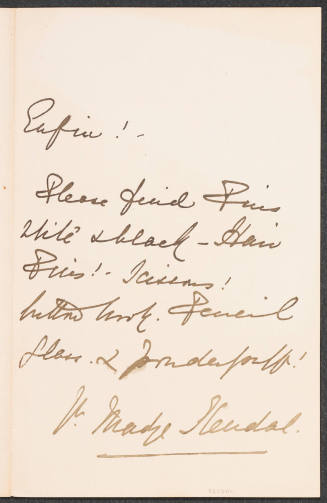

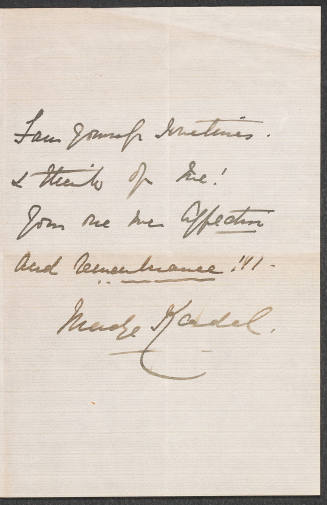

Likenesses

V. Prinser, oils, exh. RA 1883, Garr. Club · lithograph, pubd 1883 (after W. & D. Downey), NPG · J. Collier, group portrait, oils, 1904, repro. in G. Ashton, Shakespeare (1990) · W. Orpen, oils, c.1927–1928, Tate collection [see illus.] · Barraud, photograph, NPG; repro. in Men and women of the day (1888) · W. & D. Downey, photograph, NPG; repro. in W. Downey and D. Downey, The cabinet portrait gallery, 2 (1891) · H. Walpole, portrait (William Kendal), Garr. Club · photographs, repro. in Dame Madge Kendal · theatrical prints, BM, Harvard TC, NPG

Wealth at death

£4835 12s. 9d.: resworn probate, 30 Jan 1936, CGPLA Eng. & Wales · £66,251 17s. 9d.—William Kendal: probate, 27 Dec 1917, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Richard Foulkes, ‘Kendal, Dame Madge (1848–1935)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2013 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2113/view/article/34274, accessed 8 Aug 2013]

Dame Madge Kendal (1848–1935): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34274

William Hunter Kendal (1843–1917): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34275

[Previous version of this biography available here: January 2008]