Edward Alexander MacDowell

MacDowell, Edward (18 Dec. 1861-23 Jan. 1908), composer, was born in New York City, the son of Thomas MacDowell, a businessman, and Frances M. Knapp. MacDowell grew up in New York in comfortable middle-class surroundings, cultivating interests in literature, painting, music, and languages. His mother especially promoted involvement in the arts and, recognizing young Edward's talent, hoped her son would achieve fame as a concert pianist. MacDowell would indeed develop considerable pianistic talents, but he never really enjoyed performing.

When MacDowell was fifteen his mother took him to Europe to study at the Paris Conservatoire. Once enrolled he felt comfortable neither with the Conservatoire nor with Paris more generally. At the Conservatoire the large number of mechanical exercises required of him and the heavy emphasis on rote memorization were not to MacDowell's liking, though he excelled at both and ranked at the top of his class. MacDowell also disagreed with the concept of pedagogical divisions drawn between the realm of performance and that of theory and composition; they accentuated his ambivalence toward performing.

In Germany MacDowell found teachers as well as an environment that were more suited to his intellect and temperament. Consequently, after two years in Paris, MacDowell moved to Frankfurt am Main. There his talents were noticed by various conservatory masters, notably by the composer Joachim Raff. When Carl Heymann, a piano professor at Frankfurt, retired in 1880, he recommended that MacDowell succeed him. However, the conservatory board did not approve. MacDowell was then but nineteen years old.

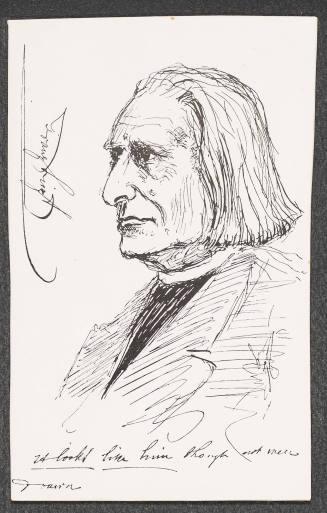

It was during his studies in Germany that MacDowell's composition talents became apparent. Raff was impressed with MacDowell's compositions and referred him to Franz Liszt. Liszt was also impressed and secured concert stages for MacDowell to present his works. Increasingly successful, MacDowell remained in Germany for eight years, writing music and teaching piano. In 1884 he married Marian Griswold Nevins (Marian Griswold Nevins MacDowell), one of his American students. They had no children. Liszt recommended MacDowell to the prestigious Leipzig publishing house Breitkopf and Härtel, which published several of his compositions, notably two piano suites, written in 1882 and 1884, and three orchestral tone poems: Lancelot and Elaine (1886), based on Tennyson's Arthurian poem, Hamlet, and Ophelia (both 1885). These works won the plaudits of European and American conductors and critics and established MacDowell as a composer of international renown.

The MacDowell's lived happily in a small cottage in the woods outside the city of Wiesbaden. They traveled widely and enjoyed the company of other Americans, notably the composer George Templeton Strong. With international fame secured, MacDowell returned to the United States in 1888, settling in Boston. For eight years he enjoyed great success there performing, teaching, and, most of all, composing. Particularly joyous and productive were the MacDowells' summers spent at a small home they bought outside Peterborough, New Hampshire.

MacDowell's compositions appealed to the tastes of the arts public in late nineteenth-century America. His orchestral works exude a fervent Romantic quality with lilting melodic lines and surging dynamics, all conveying rich emotional content. Often his orchestral tone poems were based on literary texts and poetry, particularly Keltic legends, which audiences found both pleasant and accessible. Harmonically, MacDowell's music fit within the norms of the late nineteenth-century symphonists. He did not venture heavily into the realms of dissonance that were beginning to create discomfort among some audiences and critics. Among the composers of the era, MacDowell ranked highly. One conductor, Anton Seidl, while director of the Metropolitan Opera, proclaimed MacDowell to be the superior of Brahms. While no one else placed him quite that high, MacDowell was warmly received and critically respected in both Europe and the United States, on a par with the likes of Edvard Grieg, Frederic Delius, and César Franck.

MacDowell was the best and most internationally renowned American composer of the late nineteenth century. While MacDowell's fame was considerable in his day, it has faded in the twentieth century for reasons that have little to do with any of the inherent qualities of his music. Several American critics and admirers tried to make a point of MacDowell's being a great American composer. Certain pieces, like his Indian Suite (1895) and Woodland Sketches (1896), refer to American events and scenery. He also marked some orchestral movements in English rather than in the customary Italian ("fast" rather than "allegro," for example). But MacDowell repeatedly rejected the idea that his music was specifically American. He felt that the issue of national identity was peripheral and, when imposed upon music, could distort listeners' responses. Americans, he contended, mistakenly believed that Europeans looked down on them. Nationalism in the arts, to MacDowell, created conflicts and allegiances for which there was no musical basis. Nationalism, he wrote, "has no place in art for its characteristics may be duplicated by anyone who takes the fancy to do so." He wanted Americans to progress in all areas of musical composition and performance and worked in all ways to foster this by advising young American colleagues and reviewing their work. But although MacDowell was supportive of many young artists, he would never lend his name to concerts devoted solely to American music. He believed himself to be a composer who simply happened to be American.

MacDowell's unwillingness to assert himself as a distinctly American composer contributed to the decline of his music's popularity in the early twentieth century. Had MacDowell also lived longer and written in cognizance of changing aesthetics, as he always did, his development would have cast his work differently. But as he died in 1908, the work of an artist appeared embedded in a bygone era and faced the music of overtly nationalistic rivals of subsequent generations like Charles Ives, Aaron Copland, and Roy Harris. Their precepts placed MacDowell ever further into the background, making him seem a mere curio of a former age. The composer and critic Virgil Thomson predicted that in time MacDowell's music would rebound and rank above Ives's as the greatest the nation has produced, but never in the twentieth century did such a reassessment occur.

The fate of MacDowell's music, savaged by fundamentally artless forces, was sadly mirrored elsewhere in the last decade of his life. In 1896 Columbia University president Seth Low persuaded MacDowell to move from Boston to New York and become the university's first professor of music. His teaching was highly successful, though some students found him overly refined and intellectual. New York City's rapid pace wore on him, however, and he was cut down by some nasty university politics. For three years he was Columbia's only music professor, and every detail involved in the creation of a new department fell on him: purchasing pianos and stationery, designing a curriculum, handling all correspondence, and, of course, doing virtually all the teaching. Had MacDowell had an experienced assistant and consistently sympathetic administrators, matters might have gone better. But in 1901, when Low left Columbia to become the city's mayor, Nicholas Murray Butler succeeded to the presidency. Butler and MacDowell clashed over the composer's conception of an interdisciplinary fine arts program. MacDowell felt that education in the arts was as necessary for undergraduates as training in mainstream letters and sciences. Butler, however, preferred traditional, discrete departments and resisted the idea of instituting an undergraduate requirement in fine arts. Butler also expressed his approval of the policy that relegated professors in the arts to non-voting status. These stances won Butler the political support of the most solidly entrenched in established departments, and he had his way, instituting his preferences while MacDowell was on sabbatical. Upon his return MacDowell expressed displeasure over the state of affairs at Columbia to students. After Butler had disregarded all his inquiries, MacDowell made the same problems known to several New York papers. Butler seized upon this as evidence of unprofessional behavior, and he discreetly leaked memoranda implying that MacDowell had been derelict in meeting his teaching duties. Hurt and angered by such academic warfare, for which he had neither taste nor temperament, MacDowell resigned from Columbia in February 1904.

MacDowell was greatly depressed over the Columbia debacle. This depression was aggravated by a deep malaise that came from being struck by a cab on Broadway. These injuries and depression triggered in MacDowell a general aphasia and with it a physical and emotional decline. Photographs of MacDowell taken in 1898 and 1906 reveal rapid aging. Learning of MacDowell's decline, Mayor Low sent Marian MacDowell $2,000 and confessed to her, "I feel partly responsible for this." "O! If we had never left Boston!" MacDowell lamented to his wife. His decline proceeded unabated. Doctors were powerless. Even visits to his beloved Peterborough home could not rally him. Scarcely a month after his forty-sixth birthday MacDowell passed away in New York City. Marian MacDowell maintained the Peterborough home and soon began a colony for artists there. She ran it until after World War II, and the MacDowell Colony continues to be a monument to its namesake and a haven for unfettered work in the creative arts.

Bibliography

Two biographies based on personal memories and journalistic sources appeared shortly after the composer's death: Lawrence Gilman, Edward MacDowell (1906), and John F. Porte, Edward MacDowell (1922). One biography of recent vintage in Alan Levy, Edward MacDowell: An American Master (1998). Two contemporaries wrote personal memories of MacDowell's life and work: T. P. Currier, Edward MacDowell (As I Knew Him) (1915), and W. H. Humiston, MacDowell (1924). Marian MacDowell similarly published Random Notes on Edward MacDowell and His Music (1950). Some sentimental works have appeared on MacDowell: Elizabeth Page, Edward MacDowell, His Works and Ideals (1910); Opal Wheeler, Edward MacDowell and His Cabin in the Pines (1940); and Abbie Brown, The Boyhood of Edward MacDowell (1924). W. J. Baltzell edited some of MacDowell's writings about music in Critical and Historical Essays: Lectures of Edward MacDowell Delivered at Columbia University (1912). Beyond these works there are but chapters in texts and sections in musical dictionaries and encyclopedias, the best of which is the New Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Systematic work on MacDowell has been meager, in part, because MacDowell's papers were closed until 1992. They were finally opened that year at the Library of Congress.

Alan Levy

Back to the top

Citation:

Alan Levy. "MacDowell, Edward";

http://www.anb.org/articles/18/18-00767.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Mon Aug 05 2013 16:37:20 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.