Nellie Melba

Melba, Dame Nellie [real name Helen Porter Mitchell] (1861–1931), singer, was born on 19 May 1861 in Richmond, Australia, the eldest of seven children of David Mitchell and his wife, Isabella Ann Dorn, both of Scottish descent. Her father had emigrated to Australia in the gold rush of 1852 and became a successful builder. Nellie (as she was known from childhood) learned to play the piano and first sang in public at an age which in her memoirs she gave as six. She was educated at a local boarding-school and then at the Presbyterian Ladies' College in Richmond. Her first professional teacher of singing was Mary Ellen Christian, a former pupil in England of Manuel García. The second, Pietro Cecchi, an Italian tenor with a high reputation as a teacher in Melbourne, she somewhat belatedly acknowledged as the one who did most to lay the foundations of her career.

That honour has been most widely given to Mathilde Marchesi, who took Nellie as a pupil at her Paris studio in 1886. Nellie had left Australia after a failed marriage in December 1882 to an adventurer, Charles Armstrong; they separated by mutual consent after little more than a year of marriage, during which their only child, a son, was born (they were divorced in 1900). She had then begun to study singing in earnest with the fixed idea of becoming a professional. Cecchi believed she had a great future, and after some concerts in Melbourne several discerning listeners expressed their high opinion. Unfortunately, this was not shared at first by experienced British musicians, including Sir Arthur Sullivan, for whom she auditioned in 1885 shortly after arriving in London. Sullivan offered the prospect of a small part in The Mikado after a further period of study. Instead, she went to Paris with a letter of introduction to Marchesi, reputedly the best and most influential teacher of the day.

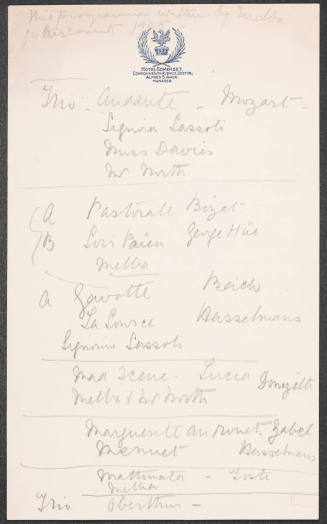

The story of Nellie's audition has become famous. ‘Salvatore!’ the teacher cried out to her husband, ‘J'ai enfin une étoile!’ Apparently, the pupil's brilliance was such that she went straight into the advanced opera class and was then sent out to launch her career after no more than nine months of tuition. Her professional name was to be Nellie Melba (partly in honour of Melbourne, the city close to her birthplace). Her operatic début occurred on 13 October 1887 at the Théâtre Royale de la Monnaie in Brussels. Her performance as Gilda in Rigoletto won enthusiastic reviews and was followed by appearances in La traviata and Lucia di Lammermoor. All three roles of this first season were to remain central to her career. The success in Brussels led to an engagement at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, where her introduction to the London public on 24 May 1888 in the title role of Lucia di Lammermoor gave little indication of the illustrious career she would eventually have in that house.

Melba's début at the Paris Opéra was a different matter. Here, on 8 May 1889, she sang the role of Ophélie in Ambroise Thomas's Hamlet and enjoyed an ovation that made her famous overnight. Her reviews told of an incomparably lovely voice with exceptional resonance in the middle register; the brilliance of her technique in florid work was admired, so too the touching simplicity of her manner and enunciation. After that, she returned in triumph to Covent Garden where she had acquired a powerful friend in Lady Gladys de Grey, later marchioness of Ripon, who had influence with leading figures at the opera house and in London society. In this second season Melba opened with Gounod's Roméo et Juliette, singing with the brothers Jean and Edouard de Reszke. This association flourished throughout the 1890s, which in both London and New York were subsequently dubbed ‘the golden age of opera’. The three singers also appeared together at St Petersburg by invitation of the tsar in 1891. In these years Melba also sang at La Scala, Milan, and in the opera houses of Palermo, Monte Carlo, Berlin, Vienna, and Stockholm and elsewhere in Europe. More important for the development of her career was her American début with the Metropolitan company on 4 December 1893. The event itself appears to have been a succès d'estime rather than a popular sensation, and it was a performance of Roméo et Juliette a little later in the season that established Melba in succession to Adelina Patti as the leading prima donna of the time. The performances she gave in these years of her absolute prime were recalled by one of New York's sharpest and most respected critics, W. J. Henderson, when he wrote of Melba shortly after her death. The quality which distinguished her from other sopranos singing in her repertory, he said, was ‘splendour’: ‘The tones glowed with a star-like brilliance. They flamed with a white flame. And they possessed a remarkable force which the famous singer always used with continence. She gave the impression of singing well within her limits’ (New York Sun, 28 Feb 1931).

An exception to that last point of Henderson's was Melba's single appearance, on 30 December 1896, as Brünnhilde in Wagner's Siegfried. The role, written for a powerful dramatic soprano, lay beyond her capabilities. The experiment was potentially ruinous, and, though the reviews were by no means uniformly bad, Melba herself was unsparing: ‘I've been a fool,’ she said. The ‘case’ became a famous one (in some quarters Jean de Reszke was wrongfully blamed as having provided encouragement), and yet the folly may not have been so unaccountable as it seemed. Melba had sung other Wagnerian roles, Elsa in Lohengrin and Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, with considerable success. Her voice at this time, by all accounts, was ample in volume with strong middle notes. In London she had sung the heavy role of Verdi's Aida, and the critics observed that her voice easily dominated the great ensembles. The Siegfried Brünnhilde, whose appearance is confined to the third act and for whom the writing lies higher in the voice than in Die Walküre and Götterdämmerung, may quite reasonably have seemed to provide an attractive, almost cautious, way into the repertory. It was not one she tried a second time.

Melba's most frequent role at the Metropolitan was that of Marguerite in Gounod's Faust, and her last appearance in the house was as Violetta in La traviata. The other major contribution she made to opera in New York was to give a needed boost to Oscar Hammerstein's venture with his Manhattan Company as a rival to the Metropolitan in 1907. Melba sang in sixteen performances, and on her last appearance was called before the curtain twenty-three times with applause continuing for forty minutes.

The opera that evening was Puccini's La Bohème (which, incidentally, was followed by the mad scene from Lucia di Lammermoor sung by Melba alone, who then had a piano brought on stage and accompanied herself in Tosti's ‘Mattinata’). The role of Mimì in La Bohème became closely identified with her throughout the remainder of her career. She sang it first in 1899 at Covent Garden, having argued strongly in its favour with a management opposed to the inclusion of such a new and plebeian opera into the ‘grand’ (summer) season. Increasingly in the new century she was criticized as a reactionary force in music. Yet she had taken part in several British premières (Goring-Thomas's Esmeralda, Bemberg's Elaine, Leoncavallo's Pagliacci, Mascagni's I Rantzau, and Hélène, the title role of which was written for her by Saint-Säens), and Bohème itself was still struggling for recognition when she took it up. She studied her role with Puccini in Italy (as she had previously done with Verdi for her Desdemona in Otello, and with Gounod, Massenet, and Delibes in Paris). It is doubtful whether she ever endowed her Mimì with the emotional warmth and fragile youthfulness the part needs, but always, even into her sixties, she brought her special purity of tone and an unforgettable top C from off-stage at the end of act I.

That note is preserved on a gramophone record of 1907, the only one Melba made with the great tenor Enrico Caruso, her partner in many stage performances. Exquisite in itself it is part of a recording in which the listener may be, initially at least, at a loss to see how it, and many of her other records, can support Melba's reputation. She recorded a repertory that for those times was quite extensive, from 1904 to 1926, though with varying success. The fine definition, purity of tone, and technical accomplishment can be recognized easily enough, but the terms of Henderson's memoir, quoted above, and especially his word ‘splendour’, may not be the first that come to mind. Even so, her records exercise a fascination and bring flashes of understanding. It is even possible, with modern reproduction, to sense something of the house-filling power that she reputedly had at her command. They can even breed affection. Tosti's ‘Serenata’, recorded in 1904, gives some notion of the thrill, in quality and ‘attack’, that her high notes could create. She can be unexpectedly moving in a simple song such as ‘Come back to Erin’; and a strangely preserved ‘distance test’ made for a recording session in 1910 suggests how excitingly full the voice could have sounded on record had the conditions been more propitious. Limitations of sensibility and in the range and depth of vocal colouring are evident too, yet it remains one of the paradoxes of the gramophone's history that this artist, so often characterized as coldly perfect, should exhibit evident faults and yet surprise her listeners by something so strongly individual, and beautiful in its individuality, that the response is emotional and warm.

Melba's personal reputation was more equivocal. An astute businesswoman, driving hard bargains with management and ruling the roost to the detriment of all foreseen rivals at Covent Garden, she could also be generous to needy causes and individuals, and she raised over £100,000 for the Red Cross during the First World War. In his memoirs, the singer Peter Dawson, a compatriot, writes that she was known in the profession as ‘Madame Sweet and Low’ (referring to ‘a sweet voice but low language’) (Dawson, 138). Honoured by people of wealth and title, she was a shameless snob, yet she would remember a flower-seller from years ago and would ask the stage hands at the opera house in Sydney, ‘Like to hear me sing, boys?’ (Hetherington, 171). Pathologically critical of other sopranos, she wrote to the choirboy Ernest Lough a letter saying that she had been trying all her life to sing ‘O for the wings of a dove’ as well as he had done at the age of fourteen.

Though her personality was too hard to be the subject of popular romantic fiction, much was made by gossip-writers of Melba's affair with Louis Philippe, duke of Orléans, who was her lover from 1890 until scandal threatened to ruin both of them two years later. A film of her life, Melba (1953), starred the young American soprano Patrice Munsel; and, more memorably, her private secretary, Beverly Nichols, wrote an infamous novel called Evensong (1932), made the following year into a film with Evelyn Laye as the vain and vindictive ageing prima donna, Irela, clearly based on his employer. But such was Nellie Melba's popularity that a number of dishes were named after her. These include Melba toast, Melba sauce (a raspberry sauce for desserts), and peach Melba. The third of these, involving both peaches and ice-cream, was created in 1892 by Escoffier, then the chef at the Savoy Hotel in London, for a party in her honour.

In the later years of her career Melba became an artistic anachronism. She enriched her concert repertory by the addition of a few French art songs, but her programmes still resorted predictably to the jewel song from Faust and ‘Home, sweet home’. In 1921 a newspaper headline ‘The diva to go home’ was gleefully greeted in the Musical Times. Feste, a pseudonym of the editor Harvey Grace, quoted the words and wrote: ‘By all means. Why not? As the Diva has melodiously declared (only too often), there's no place like it’ (MT, 409). She retired from opera eventually with a performance at Covent Garden on 8 June 1926, singing in scenes from Roméo et Juliette, Otello, and La Bohème. Some of this was recorded, including her farewell speech, in which she declared that Covent Garden was her artistic home and thanked Mr Austin, the doorman. On her return to Australia she settled at Coombe Cottage, Coldstream, near Lilydale, where she taught privately for a while, struggling courageously with illness. She died in Sydney on 23 February 1931; her death was front-page news. In Britain, where she had become a national institution and had been made a DBE in 1918 for contributions to the war effort, The Times devoted a leading article to her. In Australia, where relations had not been altogether smooth despite her bringing over an opera company of her own for several seasons, her funeral was grandly Victorian. The cortège travelled from Sydney to Melbourne where more than 5000 people passed before her coffin in the Scots church and more than 500 wreaths covered the catafalque.

J. B. Steane

Sources

N. Melba, Melodies and memories: the autobiography of Nellie Melba (1925) · J. Hetherington, Melba: a biography (1967) · W. R. Moran, ed., Nellie Melba: a contemporary review (1985) · W. J. Henderson, The art of singing (1938) · J. P. Cone, Oscar Hammerstein's Manhattan Opera Company (1964) · H. Rosenthal, Two centuries of opera at Covent Garden (1958) · G. Fitzgerald, ed., Annals of the Metropolitan Opera (1989) · private information (2004) · The Times (24 Feb 1931) · MT, 62 (1921), 409 · P. Dawson, 50 years of song (1951) · R. Fawkes, Opera on film (2000) · New York Sun (28 Feb 1931) · J. A. Simpson and E. S. C. Weiner, eds., The Oxford English dictionary, 2nd edn, 20 vols. (1989) · DNB · CGPLA Eng. & Wales (1931)

Archives

FILM

BFINA, documentary footage

SOUND

BL NSA, performance recordings · BL NSA, documentary recording · BL NSA, news recording · BL NSA, oral history interview

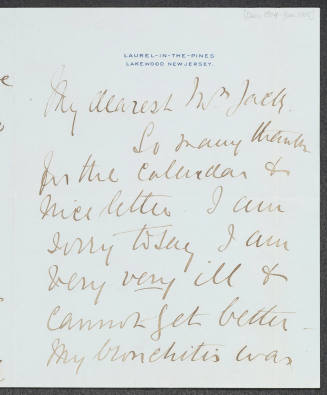

Likenesses

B. Mackennal, bust, 1899, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne · H. W. Barnett, photograph, in or before 1903, Royal Opera House, London [see illus.] · R. Tuck & Sons, postcard, c.1904, NPG · R. Bunny, portrait, repro. in Hetherington, Melba, frontispiece · photographs, Royal Opera House, London · photographs, Metropolitan Opera House, New York · photographs, NL Aus. · postcard, NPG

Wealth at death

£43,095 19s. 9d.: Australian probate sealed in England, 22 Aug 1931, CGPLA Eng. & Wales · approx. $1,000,000: wire service

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

J. B. Steane, ‘Melba, Dame Nellie (1861–1931)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/34978, accessed 6 Aug 2013]

Dame Nellie Melba (1861–1931): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34978