Pierre Monteux

Monteux, Pierre Benjamin (4 Apr. 1875-1 July 1964), conductor, was born in Paris, France, the son of Gustave Elie Monteux, a shoe salesman, and Clémence Brisac, a piano teacher. Monteux's honors included commander of the Légion d'honneur and knight of the Order of Orange-Nassau. His early musical education was at the Paris Conservatory, where he studied violin and composition. In 1896 he shared the conservatory's premier prix for violin with the young French violinist Jacques Thibaud, who after the turn of the century became one of the most well known violinists of his generation. During his student years Monteux played a viola with the orchestra at the Opéra-Comique, participating in the premiere of Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande in 1902, and with the Concerts Colonne, one of the main subscription concert series in Paris at the time. He later became chorus master and assistant conductor of the Concerts Colonne. In 1894 he became a member of the Geloso String Quartet and remained with that ensemble until 1911. Between 1908 and 1914 he conducted the Casino Orchestra in Dieppe. In 1911 Monteux was engaged by the Russian impresario Serge Diaghilev to conduct concerts of his Ballets Russes. As a result of his association with the Ballets Russes, Monteux's international reputation as a leading exponent of contemporary music, especially by French composers, was established. Notable premieres conducted by Monteux during this period include Debussy's Jeux (1913), Ravel's Daphnis et Chloé (1912), and Igor Stravinsky's Le sacre du printemps (1913), a premiere infamous for the riotous audience reaction to the unusual music and choreography. During this early period of his life Monteux was married twice: first to a pianist from Bordeaux (name unknown), and then to Germaine Benedictus, with whom he had three children.

Following wartime service in the French Thirty-fifth Territorial Infantry, Monteux came to the United States for the first time, in 1916-1917, on a tour with the Ballets Russes. From 1917 to 1919 he was engaged by the Metropolitan Opera in New York City as conductor of the French repertory. While at the Metropolitan in 1918 he conducted the American premiere of Rimsky-Korsakov's last opera, The Golden Cockerel (1909), and the ballet version of Henry F. Gilbert's The Dance in Place Congo (1913).

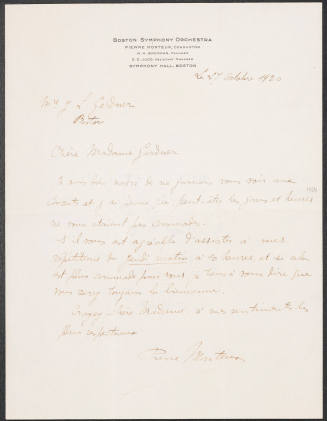

After a brief period as guest conductor, Monteux was engaged as conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1919, a position he held until 1924. He came to Boston in the midst of an acrimonious strike by the musicians, and after almost thirty players walked out, he had to rebuild the orchestra nearly from scratch. While in Boston, Monteux worked to acquaint his audience with both new works and music outside the Germanic repertoire that had previously been the standard fare in Boston under a series of German-born conductors. Though he was well liked personally in Boston, the music he performed was not always given the same respect. He laid the groundwork, however, for his successor, Serge Koussevitzky, who was also a devoted proponent of new music. In 1924 he moved to Amsterdam to become the principal guest conductor, under Willem Mengelberg, of the Concertgebouw Orchestra. Monteux married Doris Gerald Hodgkins, of Hancock, Maine, in 1928; they had no children.

In 1929 Monteux founded the Orchestre Symphonique de Paris, which presented concerts, including many premieres, until the onset of World War II in 1938. Like many European musicians, Monteux then found a position in the United States that provided a haven from the upheavals in Europe. In 1936 he was engaged as conductor of the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, a position he held until 1952. He became a U.S. citizen in 1942. Monteux's tenure in San Francisco propelled the orchestra's rise to international stature, enhanced by forty recordings and a successful national tour in 1947.

Following his retirement from the San Francisco Symphony, Monteux performed widely in the United States and Europe as a guest conductor, often conducting opera. In 1961 he signed a twenty-five-year contract with the London Symphony Orchestra. With this orchestra, he conducted the fiftieth anniversary performance of Le sacre du printemps in 1963.

Monteux was involved throughout his career with the education of musicians. He was the first in a generation of French-born musicians, including the pianist E. Robert Schmitz, who built their reputations on profound musicianship, restrained yet vigorous performances, and a commitment to the musical education of both aspiring musicians and audiences. In 1932 he established the École Monteux in Paris to coach young conductors, and he continued this work during his summers in Maine after immigrating to the United States. His students include Neville Marriner and André Previn.

Monteux disliked recording because of the lack of spontaneity inherent in the process. However, Monteux's recordings, while not plentiful, are among the finest ever made of the French repertory. His aesthetic restraint and thorough preparation of his orchestras resulted in sensitive, energetic, and authoritative readings of the scores.

In performance, Monteux was, as Stravinsky once said of him, "the [conductor] least interested in calisthenic exhibitions for the entertainment of the audience and the most concerned to give clear signals for the orchestra." For all of his precision, however, it was the lyricism and grace of Monteux's performances that remain their most memorable characteristic.

Bibliography

Most of Monteux's personal papers and scores were destroyed during World War II. His career is covered in two books by his wife, Doris G. Monteux: It's All in the Music (1965, with discography by Erich Kunzel), and, under the pseudonym Fifi Monteux, Everyone Is Someone (1962). Other books with information on Monteux during his years in San Francisco include L. W. Armsby, We Shall Have Music (1960) and David Schneider, The San Francisco Symphony: Music, Maestros and Musicians (1983, with a foreword by Edo de Waart). Evaluations of Monteux may be found in the following general surveys: David Ewen, Dictators of the Baton (1948), Hope Stoddard, Symphony Conductors of the U.S.A. (1957), and Harold C. Schonberg, The Great Conductors (1968). Monteux's career and recordings are sympathetically surveyed in Samuel Lipman, "A Conductor in History," Commentary 77 (Jan. 1984): 50-56, and J. Canarina, "Pierre Monteux: A Conductor for All Repertoire," Opus, Apr. 1986, pp. 14-19. The following is a list of CD reissues of recordings by Monteux made during the 1950s and 1960s: Beethoven, Symphony no. 3 (Philips 420 853-2); Berlioz, Overture: Béatrice and Bénédict (RCA GD 86805); Chausson, Poème de l'amour et de la mer (EMI mono CMS7 63549-2); Debussy, Images and Le Martyr de St. Sébastien (Philips 420 392-2); Franck, Symphony in D Minor (see Berlioz); d'Indy, Symphonie sur un chant montagnard français (see Berlioz); Massenet, Manon (see Chausson); Ravel, Boléro, Ma Mère l'Oye, La Valse (Philips 420 869-2); Ravel, Daphnis et Chloé, Pavane pour une infante défunte, Rapsodie espagnole (Decca 425 956-2); Rimsky-Korsakov, Scheherazade (Decca 421 400-2); and Tchaikovsky, Swan Lake (Philips 420 872-2). An obituary is in the New York Times, 2 July 1964.

Ron Wiecki

Back to the top

Citation:

Ron Wiecki. "Monteux, Pierre Benjamin";

http://www.anb.org/articles/18/18-00858.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Mon Aug 05 2013 17:06:17 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.