Anna Pavlova

Pavlova, Anna Pavlovna [formerly Anna Matveyevna Pavlova] (1881–1931), ballet dancer, was born in St Petersburg on 31 January/12 February 1881 according to an entry in the register of the St Petersburg military hospital; she later changed her second name to Pavlovna. Her mother, Lyubov Fyodorovna Pavlova, a laundry maid, was married to a reserve soldier, Matvey Pavlov; but Anna was most probably the illegitimate daughter from an earlier relationship with a reserve soldier or minor official. There is also the suggestion that she was partly Jewish, which would have reinforced the social stigma of her birth in imperial Russia. Pavlova spent her childhood with her grandmother at Ligovo, outside St Petersburg, but in 1890 she was taken to see The Sleeping Beauty, the newly created ballet by Marius Petipa and Pyotr Tchaikovsky, at the Maryinsky Theatre. The production, music, and dancing captured Pavlova's imagination, and from then on she was determined to become a ballerina, although she had to wait two years to qualify for Imperial Ballet School. Ironically, having wanted to be Princess Aurora (a role she first danced in 1908), she never found this a character to which she was totally suited.

Early success

At the age of eleven Pavlova made her first recorded appearance at the Maryinsky in The Magic Fairy Tale, choreographed by Marius Petipa for pupils of the school. In 1898 she made her official début in the pas de trois from Pharaoh's Daughter, some six months before graduating in April 1899, when she danced in Aleksandr Gorsky's Clorinda and Pavel Gerdt's Imaginary Dryads. Her rise through the company was swift and measured. She began as a coryphée and was promoted annually so that in 1906 she had reached the rank of ballerina.

Apparently frail in physique, Pavlova looked different from other dancers of the day (who tended to be stockier and more muscular than later dancers). Almost immediately she was singled out from her contemporaries for being graceful, soft, and feminine. It was these qualities rather than an outstanding technique that attracted attention. She was not a virtuoso dancer in the popular Italian style of the day, but she could be dramatic, poetic, flirtatious, or comic as roles required. She also performed lively character dances. On stage she hid her technique, but her line was impeccable and her arabesque and pas de bourrée unsurpassed. Dance was her religion: she was totally dedicated to the art. Like most dancers she worked on her technique throughout her career. In 1903 she and the ballerina Vera Trefilova travelled to Milan to study with Caterina Beretta, and in 1906 she engaged Enrico Cecchetti as her private teacher knowing that he had helped other dancers, most notably Olga Preobrazhenska, overcome their weaknesses.

Among Pavlova's first successes were her Zulme in Giselle in September 1899 and her first created role, Hoarfrost in The Seasons in February 1900. In 1902 she consolidated her success by dancing Nikiya, the temple dancer heroine of La bayadère, and in 1903 the title role in Giselle. These ballets suited her, and used both her dramatic ability and outstanding ethereal lightness. Giselle was a ballet she continued to dance throughout her career. Although she would have liked to dance Nikiya in the West, La bayadère seemed too quaintly old-fashioned for audiences in the 1920s. As Nikiya and Giselle, Pavlova caught the attention of the ageing Marius Petipa, whom she asked to coach her in his ballets. Although at the end of his career, Petipa was still willing to adapt roles to show off the talent of dancers he wanted to encourage, and for her début in the title role of Paquita, he created a new variation to music for the harp by Riccardo Drigo.

Pavlova also worked with the next generation of choreographers, particularly the reformers Aleksandr Gorsky and Michel Fokine, both of whom welcomed her ability to act through dance. Both introduced a new plasticity to their dances, and Pavlova was a noted exponent of this new free-flowing style. In Gorsky's revised versions of established ballets, which replaced balletic clichés with an attempt at dramatic logic, Pavlova was called on to perform at the imperial theatres in both St Petersburg and Moscow. For Gorsky, Pavlova danced Kitri in Don Quixote and Bint-Ana in Pharaoh's Daughter. For Michel Fokine (also one of her regular partners at the Maryinsky) Pavlova created Armida in Le pavillon d'Armide, the Sylph of the Waltz in his first Chopiniana (which inspired his subsequent Les sylphides), and several other roles. Fokine's solo The Swan, danced to an extract from Camille Saint-Saëns's Carnival of the Animals, became Pavlova's signature work from the time she first danced it at a gala in December 1907. This minute dance encapsulates a whole history. Although it is based on classical steps, a series of pas de bourrée broken by an occasional attitude, the dancer's arms are expressive rather than formally academic, and thus it has been seen as a synthesis of traditional and modern. This was a synthesis that was symbolic of Pavlova's approach to her career.

In St Petersburg, Pavlova surrounded herself with influential supporters, as was necessary for the advancement of a ballerina. Most significant among these men was the aristocratic balletomane Victor Dandré, who set her up in an apartment with a ballet studio on the Angliisky Prospekt. Dandré was a member of the St Petersburg city council, but in 1911 he was arrested on a charge of appropriating vast sums of government money. He forfeited bail when Pavlova returned from America, and went with her to London. Pavlova remained loyal to Dandré, who became her manager (there is no evidence that they were ever married—indeed, her private life remains something of an enigma), setting up her tours and encouraging her to dance popular, easily accessible ballets for new audiences rather than to create more avant-garde works.

International career

Pavlova had embarked on her international career in 1908. After performing at Riga in Latvia in February, she undertook a tour of Scandinavia in May. It was in Stockholm, where she gave six performances, that she realized the value of her art. As she noted in her brief memoir, Pages of my Life, she was overwhelmed by crowds at her hotel after her performances and at the railway station to see her depart. She asked her maid, ‘But what have I done to move them to so great an enthusiasm?’ Her maid replied, ‘Madam, you have made them happy by enabling them to forget for an hour the sadness of life.’

In 1909 Serge Diaghilev invited Pavlova to be ballerina of the group he was taking to Paris. She agreed, but having previously committed herself to a spring tour of central Europe—Berlin, Leipzig, Prague, and Vienna—arrived in Paris only in June, when the season was already under way. She nevertheless scored a great success with Vaslav Nijinsky in Les sylphides and with Michel Fokine in Cléopâtre. Although Diaghilev had plans to work with her the following year, it is said that her conservative outlook clashed with the impresario's thirst for modernity. She refused the title role in The Firebird because she found Igor Stravinsky's score ugly. She had anyway become too involved in her own tours, and returned to the Ballets Russes only for its second London season at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in 1911. Here she had the chance to be seen with Nijinsky in Giselle, Cléopâtre, Le pavillon d'Armide, Les sylphides, and the pas de deux L'oiseau d'or. This was the season in which audiences had the opportunity to compare two great ballerinas, Pavlova and Tamara Karsavina. Perhaps it was their fellow dancer Lubov Chernyshyova who explained most clearly the contrast between the two artists. Karsavina ‘was the most beautiful woman, all warm, wonderful woman. But Pavlova, when she danced—not woman at all—spirit!’

By this time Pavlova was a star in London in her own right. In 1909 she had travelled from Paris to London, where, partnered by Michel Mordkin, she danced for the king and queen. On 18 April 1910 Pavlova opened at the Palace Theatre, London, in a programme of divertissements as part of a variety bill. The dancers' repertory included pas de deux and duets for Pavlova and Mordkin: the exuberant and frenzied Bacchanale to music from Glazounov's The Seasons, the flowing Valse caprice to music by Anton Rubinstein; and solos for Pavlova: Le papillon, La rose mourante, and of course The Swan, all of which were acclaimed by the public. Pavlova's season in London was sandwiched between trips to the United States of America. During the first of these she made her début there in Coppélia at the Metropolitan Opera House, New York, and made brief visits to Boston and Baltimore. In the autumn Pavlova and Mordkin embarked on a nationwide tour with a full corps de ballet for which Mordkin staged Giselle and an exotic new work, The Legend of Aziade.

For her initial overseas tours Pavlova received leave of absence from the imperial theatres, between which she would return to the Maryinsky stage. At the start of her second American tour she requested leave for two years, and when it was refused she paid a large forfeit to break her contract. Nevertheless she returned to St Petersburg to dance in 1911 and 1913 and became cut off from Russia only by the First World War and the revolution. From 1912 she made London her base, living at Ivy House, Golders Green (on the edge of Hampstead Heath), which she purchased in 1914. Having already used English children for her production of Snowflakes (a version of ‘Land of snow’ from The Nutcracker) at the Palace Theatre in 1911, she began to train English recruits. After teaching her pupils at Ivy House she started employing English dancers for her company, including Muriel Stuart and Hilda Butsova (Boot), both of whom took over some of her own roles.

Popularizing classical ballet

Anna Pavlova played a major role in popularizing fine classical ballet, introducing much of the work of Petipa (sometimes in the form of later revisions) to audiences outside Russia. These, rather than the innovations of other contemporary companies, are the ballets that have stood the test of time and are now danced by classical companies throughout the world. Much has been made of Pavlova's alleged artistic conservatism. It is true that she was not at home with music by Stravinsky, and the designs for many of her productions were merely routine, but she had helped Michel Fokine establish his programme of reforms, employed Leon Bakst as designer when she could, and at the end of her career invited Georges Balanchine to choreograph for her company. She recognized the taste of her audiences and tailored her programmes accordingly, demonstrating to them Russia's rich choreographic heritage. Many of her productions were staged by her ballet masters or her partners, who had to adapt large, spectacular works to the resources of a relatively small touring company. Even when the resources of Charles Dillingham's New York Hippodrome were available to Pavlova in 1916, so that she could mount a production of The Sleeping Beauty, it was only as one turn in The Big Show, and this ballet seems to have been too sophisticated for American taste at that time.

For twenty-two years Pavlova toured unceasingly, dancing in major cities and smaller towns, sometimes in venues at which ballet was unknown. She danced in opera houses, on open-air stages, and in public spaces such as bullrings in Mexico. Conditions were often difficult, and although her partners and company sometimes complained, Pavlova's missionary zeal carried her on. Having sailed to the United States in 1914 at the outbreak of war, she performed in North America and Cuba until 1917, when she embarked on a two-year tour of South America and did not return to Europe until 1919. Pavlova's punishing itinerary for 1914–16 is reproduced in Keith Money's Anna Pavlova: her Life and Art (1982). In 1922–3 Pavlova took her company to east Asia; in 1926–7 to South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand (where the meringue-based dessert crammed with fruit and cream was created and named for her); in 1928–9 she went on what proved to be her last world tour. Over a period of eight months Pavlova travelled extensively, dancing in South America, Egypt, India, Burma, Malaya, Australia, and elsewhere.

Much of Pavlova's work had instant appeal, and she was ideal as a representative of ballet for inclusion at London's first ‘Royal variety show’ on 1 July 1912; but she also presented some considerably more sophisticated programmes for opera house stages. In the 1920s these included dances learned on the company's world tours, and introduced a serious multiculturalism not found in other companies. Although most of her ballets were arranged for her company by others, Pavlova created a number of her own solos to considerable effect. She also choreographed a one-act ballet, Autumn Leaves, to music by Chopin in 1920, in which she played a chrysanthemum buffeted by the north wind; it is eventually picked, but then tossed aside by a poet. The ballet reflected her use of images drawn from nature, which also featured in the solos she made for herself.

Pavlova was one of the first great theatre artists who appreciated the value of film. Although dissatisfied with most of the results, she persevered with the new medium, recording some of her divertissements as well as providing glimpses of some of the larger works she presented. These were made by professional cameramen in Hollywood or for newsreels, or as home movies, and a compilation (assembled by Dandré) was released as The Immortal Swan in 1935. Pavlova also appeared in the feature film The Dumb Girl of Portici (1916), which she made to fund her company's tours in the United States of America. This is, in some senses, the best record of her artistry. Her joyous tarantella on the seashore and her helplessness and horror when trapped in a rat-infested prison indicate her range as an artist.

Final years

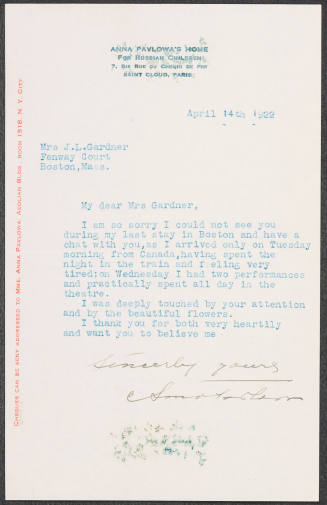

Off-stage Pavlova accepted her role as a public figure and was always immaculately turned out. Her image was frequently used for advertising purposes by companies wanting to sell, for example, shoes, pianos, or face creams. Pavlova expected members of her company to create a good impression. She demanded much of her dancers, but she was also concerned for their development and welfare, and the parties she gave her whole company each Christmas became legendary. Although in most photographs she is fashionably attired, when relaxing away from the public gaze she frequently wore trousers. Pavlova's life centred upon the stage, but she had outside interests. She was actively involved in charity work, establishing and funding an orphanage at St Cloud outside Paris for destitute Russian children, and she was passionately fond of animals and birds; her menagerie at Ivy House included dogs and swans. She was also a talented sculptor.

It seems that Pavlova could never have been happy without performing, and as a result of her constant work burnt herself out. Her autumn tour of Britain in 1930 ended with a final performance at Golders Green Hippodrome, in which she danced in Amarilla, Gavotte, and The Swan and performed the grand pas from Paquita. After a short break in the south of France she travelled to the Netherlands for the start of her next tour. On the journey she caught a chill; she contracted pneumonia, which turned to pleurisy, and died at the Hôtel des Indes in The Hague on 23 January 1931. She was cremated at Golders Green, London. Her partner, Victor Dandré, outlived her.

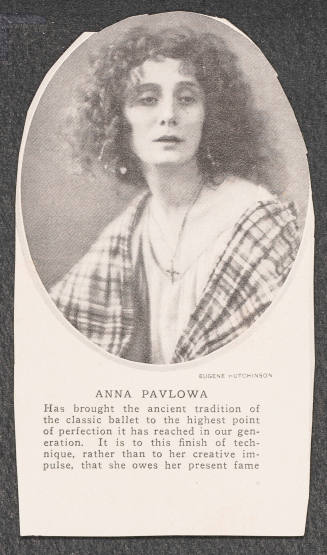

During her lifetime Anna Pavlova was the best-known ballerina in the world. She toured worldwide, and, internationally, her name and the key roles that she danced became synonymous with ballet. As an indefatigable ambassador for her art, she made it her greatest legacy to inspire a whole generation to study ballet, to dance, and to choreograph. Frederick Ashton, for example, repeatedly described how she ‘injected him with the poison’ that made him want to be a ‘ballerina’ and then to dance and choreograph. He drew inspiration from his recollections of her performances for many of his creations. Pavlova was slim and ideally proportioned, which gave the illusion that she was taller than her height of 5 feet 3 inches. With her small head on its slender neck and her dark hair drawn back, her physical appearance came to typify what the public expected of a ballerina. Her dancing had a stellar quality that convinced an uninitiated audience that they were in the presence of theatrical greatness.

Jane Pritchard

Sources

H. Algeranoff, My years with Pavlova (1957) · V. Dandré, Anna Pavlova in art and life (1932) · M. O. Devine, ‘The swan immortalized’, Ballet Review, 21 (summer 1993), 67–80 · M. Fonteyn, Pavlova: portrait of a dancer (New York, 1984) · A. H. Franks, ed., Pavlova: a biography (1956) · W. Hyden, Pavlova: the genius of the dance (1931) · J. Lazzarini and R. Lazzarini, Pavlova: repertoire of a legend (New York, 1980) · K. Money, Pavlova: her life and art (1982) · T. Stier, With Pavlova round the world (1929) · V. Svetlov, Anna Pavlova (1931) · O. Verensky, Anna Pavlova (1973) · DNB

Archives

Museum of London, costumes and other material

FILM

BFINA, version of The immortal swan · Museum of Modern Art Film Archive, New York, The dumb girl of Portici, Universal Studios (1916) · Museum of Modern Art Film Archive, New York, The immortal swan, (1935) · Pathé archives, newsreel material

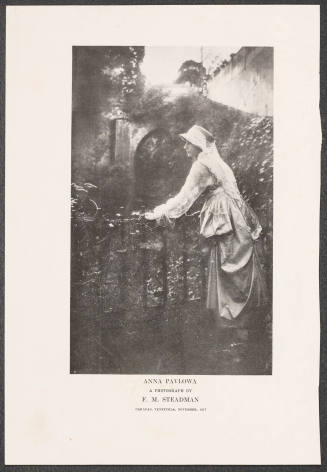

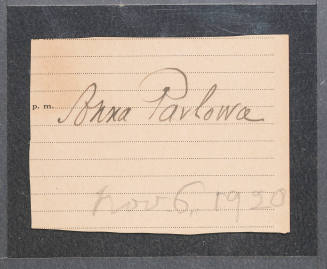

Likenesses

J. Lavery, portrait, 1911, Tate collection [see illus.] · V. Gross/Hugo, portrait · M. Hoffman, sculptures · Javovleff, portrait · J. Lavery, portrait · Legat, caricature · Schuster-Woldan, portrait · V. Serov, Russian Museum, St Petersburg · Sorine, portrait · Steinburg, portrait · A. Stevens, portraits · photographs

Wealth at death

£14,147 18s. 7d.: administration, 24 April 1931, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Jane Pritchard, ‘Pavlova, Anna Pavlovna (1881–1931)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/37836, accessed 6 Aug 2013]

Anna Pavlovna Pavlova (1881–1931): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/37836