Ronald Storrs

Storrs, Sir Ronald Henry Amherst (1881–1955), colonial governor and Middle Eastern specialist, was born at Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, on 19 November 1881, the eldest son of the Revd John Storrs (c.1825–1928), who at the time was vicar of St Peter's, Eaton Square, London, and became dean of Rochester in 1913, and his wife, Lucy Anna Marie Cust (d. 1923), sister of the fifth Earl Brownlow. Educated at Temple Grove School, East Sheen, Surrey, and then at Charterhouse School where he held a classical scholarship, Storrs took a first-class classical tripos at Pembroke College, Cambridge, in 1903. Storrs and Mark Sykes then both studied Arabic at Cambridge under Professor E. G. Browne. Although Storrs had an undergraduate education only in Eastern languages and literature, service in the Egyptian civil service between 1904 and 1909 led to his appointment in 1909 as oriental secretary at the British agency in Cairo under Sir Eldon Gorst.

Highly regarded by Lord Kitchener when he was consul-general in Cairo, Storrs was intimately involved from the time of the initial approaches to the British government by Abdullah, son of Hussein, the sherif of Mecca, about the likely British attitude to the Arabs exercising their rights in their own country. Abdullah suggested a relationship between Britain and Arabia in which the Arabs would have internal self-rule and Britain would administer foreign relations, an idea Storrs liked and which was compared to the relationship between Afghanistan and Britain. Storrs helped to change a reply to Abdullah from giving the assurance that Britain would protect the Arabs against invasion from abroad to pledging British support for the emancipation of the Arabs. When he was appointed minister of war Kitchener wanted Storrs's assistance in London, but as this was not allowed by government regulations Storrs returned to Cairo and from there inspired and manipulated British policy in the Middle East. Even with the appointment of Sir Henry McMahon as high commissioner in Egypt in December 1914, Storrs and his fellow British officials in the protectorate continued to look upon Kitchener as their chief.

At this time Storrs incorrectly advised Kitchener that Muslims would oppose a Jewish Palestine because they blamed Jews for the war; the evidence is that Muslim opposition went back much earlier and arose from Jewish colonization in the area. The intelligence operation in Cairo run by Storrs and Gilbert Clayton was flawed in that the men had only a limited understanding of the local population, failed to grasp that Middle Eastern Muslims were not prepared to be ruled by non-Muslims, and relied on uncorroborated information. Storrs's particular scheme was to replace the Ottoman empire in the Arabic-speaking Middle East by a new Egyptian empire, and it included the expectation that Syria could be incorporated into British Egypt as the Syrians were thought to prefer the British to the French. Kitchener developed a Middle East policy based on Storrs's proposal. When Mark Sykes, then a member of the committee on Asiatic Turkey, went to Cairo in the middle of 1915 to sound out British officials as to their reaction to a division of Arabia between Britain and France, he was won over to Storrs's Egyptian empire scheme. Sykes was converted to a policy favouring Hussein as having political power over the Arabs. Storrs also wanted the annexation of Palestine and its incorporation into Egypt.

Storrs was implicated in the controversies over the subsequent Hussein–McMahon correspondence which forms the basis of the Arab claim that Britain promised an independent Arabia after the end of the war in return for assistance in driving out the Turks by the raising of the Arab revolt. On 14 July 1915 Hussein sent a messenger to Cairo with a note. It arrived five weeks later. McMahon's initial reaction was favourable. Storrs, who did the translation, was not so impressed. Hussein explained that the Arabs had decided to regain their freedom; they hoped for British assistance. Emphasizing the identity of British and Arab interests, the sherif proposed a defensive and conditionally offensive alliance. The terms included British recognition (acknowledgement) of the independence of the Arab countries, from Mersina and along the latitude of 37° to the Persian frontier in the north, bounded in the east by the Gulf of Basrah, in the south by the Indian Ocean with the exception of Aden, and in the west by the Red Sea and the Mediterranean up to Mersina. Storrs noted that the sherif had no mandate from other potentates, knew that he was demanding more than he could expect, and that the boundaries should be reserved for subsequent discussion. These points were taken up by McMahon in his advice to the Foreign Office. It is difficult to ascertain what transpired in these negotiations as the position in the Arab movement of Muhammad al-Faruqi, the intermediary through whom the sherif's communications were made, is unclear, as is the extent to which he and Storrs were able or willing to translate and interpret the messages for their superiors. Storrs admitted to being under pressure, and having for an assistant someone whose Arabic was only fair. Storrs's own knowledge of written Arabic was limited. He was frequently away and others did the work then, and often the messages were verbal and not recorded.

Storrs was part of the Arab bureau formed in Cairo in December 1915, to which T. E. Lawrence was attached in January 1916, and a shared interest in classics led to a lasting friendship between the two men (Storrs was the principal pallbearer at Lawrence's funeral in 1935). On 10 June 1916 Hussein raised the Arab revolt, but the momentum seemed uncertain and in October 1916 Storrs secured permission to take Lawrence as a companion on a mission to Jiddah to reorganize it.

In Seven Pillars of Wisdom Lawrence wrote of Storrs as being the most brilliant Englishman in the Middle East and described his love of music, literature, sculpture, and painting, but also suggested his limitations:

His shadow would have covered our work and British policy in the East like a cloak, had he been able to deny himself the world, and to prepare his mind and body with the sternness of an athlete for a great fight. (Lawrence, 57)

Lawrence recorded that on board ship, en route for Jiddah, Storrs discoursed with Aziz al-Masri, an Arab leader, on Wagner and Debussy while sitting in a red leather armchair and that the great man's sweat turned the seat of his trousers a vivid scarlet. A portrait of Storrs by John Singer Sargent is reproduced in the publicly circulated 1935 edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdom. According to Harry Luke, his successor as oriental secretary in Egypt, Storrs had ‘a surprisingly cosmopolitan outlook on life, to which were added a discriminating taste, a Voltairian cynicism, a lucidity of thought ... and a wide but critical and discriminating appreciation of the good things of this life’ (DNB).

In 1917 Storrs served as assistant political officer to the Anglo-French mission of the Egyptian expeditionary force and was also attached to the secretariat of the British war cabinet. At the end of 1917 he was appointed military governor of Jerusalem and served in that capacity until 1920 when he became civil governor of Jerusalem and Judea (1920–26). The Zionists did not like him and he was the focus of an anti-British propaganda campaign. Although the model of what Zionists hoped for from a British administrator, a man who shared their cultured interests in fields of literature, music, and languages—something regarded as unusual in British leaders at that time—Storrs was also vain and arrogant. But, above all, he believed in fairness, and in that he was the model British civil servant. This attitude is evidenced as late as 1940 when he wrote in his updated account of Zionism, Lawrence of Arabia: Zionism and Palestine, of the need to see that ‘both halves of the mandate are faithfully and practicably maintained’ (p. 128). When the war cabinet's Middle East committee sent a Zionist commission, led by Chaim Weizmann, to Palestine in January 1918 to see to the implementation of the Balfour declaration, Storrs, speaking ‘as a convinced Zionist’, thought the commission ‘lacked a sense of the dramatic activity’: the Balfour declaration hardly opened for the inhabitants of Palestine ‘the beatific vision of a new Heaven and a new Earth’ (Ovendale, 44). Members of the Zionist commission successfully opposed the appointment of Storrs as chief administrator.

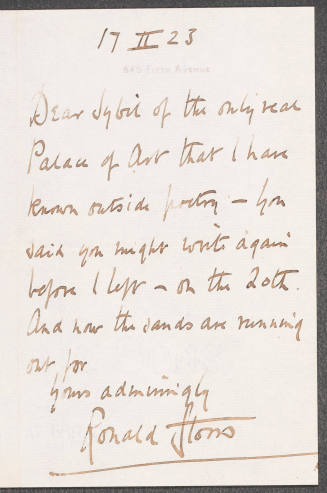

As civil governor Storrs left much of the administration to subordinates and instead concentrated on a cultural and aesthetic transformation of the city, founding Pro-Jerusalem, a society for the protection and preservation of antiquities, and brought in Charles Ashbee, the architect, as town planner. The informed in the city were, however, conscious that Storrs pretended to be a better linguist than he was, and thought that he could not be wholly trusted and was open to trickery—which he used, for example, to secure the removal of an ugly partition in the church of the Nativity at Bethlehem. Storrs gave a much more favourable account of the latter action in his best-selling memoirs, Orientations (1937). This work provided a wonderfully vivid personal account of a critical juncture in the history of the Middle East.

Appointed in 1926 as governor of Cyprus, Storrs was quoted by Greek Cypriots as saying: ‘A man is of the race of which he passionately feels himself to be.’ There is a photograph of Storrs as governor of Cyprus in H. D. Purcell's Cyprus (1959; between pages 224 and 225). As governor he secured the cancellation of Cyprus's share of the Turkish debt, but countered demonstrations in favour of enosis (union with Greece), by deporting ten ringleaders. In 1931 Government House and Storrs's art collection were burnt. At the end of his term, in 1932, Storrs was appointed as governor of Northern Rhodesia, a virtual exile which he did not enjoy. In his memoirs Northern Rhodesia is hardly mentioned, apart from the intolerable social protocol where the only black person a white man could shake by the hand was the Lozi (Barotze) paramount. He oversaw the transfer of the capital from Livingstone to Lusaka, but was not in the colony long enough to make an impression and in 1934 was invalided out of tropical service in circumstances that have never been explained.

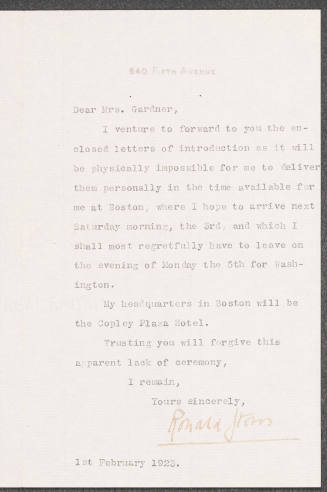

Storrs married Louisa Lucy, daughter of Rear-Admiral the Hon. Algernon Charles Littleton and widow of Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Arthur Clowes, in 1923. They had no children; she died in 1970. He served as member for East Islington on the London county council between 1937 and 1945, and with various music and church organizations, and made Ministry of Information broadcasts between 1940 and 1945. He was appointed CMG (1916), CBE (1919), and KCMG (1929); he was knighted in 1924. He was a knight of justice of the order of St John of Jerusalem, a commander of the Crown of Italy, and received the order of St Saviour of Greece. He was awarded honorary doctorates by Aberdeen University and Trinity College, Dublin. He died at St Stephen's Hospital, Chelsea, London, on 1 November 1955, after an illness.

Ritchie Ovendale

Sources

R. Storrs, Orientations (1937) · D. Fromkin, A peace to end all peace: creating the modern Middle East, 1914–1922 (1989) · B. Westrate, The Arab bureau: British policy in the Middle East, 1916–1920 (1992) · R. Ovendale, The origins of the Arab–Israeli wars, 3rd edn (1999) · R. Storrs, Lawrence of Arabia: Zionism and Palestine (1940) · R. Adelson, Mark Sykes: portrait of an amateur (1975) · H. Luke, Cities and men, 3 vols. [1953–6], vol. 2 · C. Sykes, Cross roads to Israel (1965) · B. Wasserstein, The British in Palestine: the mandatory government and the Arab–Jewish conflict, 1917–1929, 2nd edn (1991) · L. H. Gann, A history of Northern Rhodesia: early days to 1953 (1964) · H. D. Purcell, Cyprus (1969) · R. Stephens, Cyprus, a place of arms: power politics and ethnic conflict in the eastern Mediterranean (1966) · D. Stewart, T. E. Lawrence (1979) · T. E. Lawrence, Seven pillars of wisdom: a triumph, new edn (1962) · E. Samuel, A lifetime in Jerusalem: the memoirs of the second Viscount Samuel (1970) · Viscount Samuel [H. L. S. Samuel], Memoirs (1945) · J. Bowle, Viscount Samuel: a biography (1957) · M. Yardley, Backing into the limelight: a biography of T. E. Lawrence (1986) · P. Knightley and C. Simpson, The secret lives of Lawrence of Arabia (1971) · J. Kimche, Palestine or Israel: the untold story of why we failed, 1917–1923, 1967–1973 (1973) · CGPLA Eng. & Wales (1956) · DNB

Archives

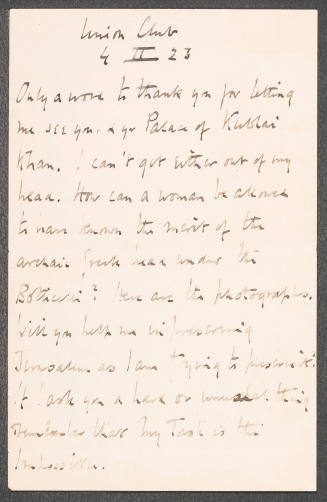

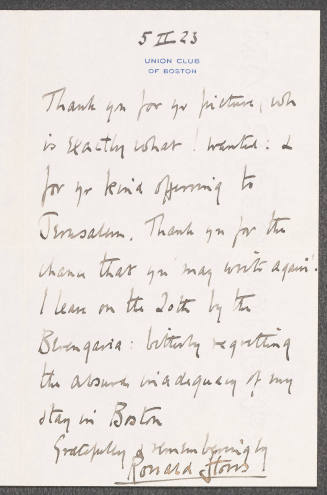

NRA, priv. coll., corresp. and papers relating to Middle East and T. E. Lawrence · Pembroke Cam., corresp., diaries, and papers, mainly relating to Middle East · St Ant. Oxf., Middle East Centre, notes and lecture on T. E. Lawrence :: BL, corresp. with Society of Authors, Add. MS 63334 · Harvard University, near Florence, Italy, Centre for Italian Renaissance Studies, letters to B. Berenson and M. Berenson · King's Lond., Liddell Hart C., corresp. with Sir B. H. Liddell Hart · Parl. Arch., letters to Herbert Samuel · Ransom HRC, corresp. with T. E. Lawrence · St Ant. Oxf., Middle East Centre, corresp. with Humphrey Bowman · St Ant. Oxf., Middle East Centre, corresp. with H. St J. B. Philby · TNA: PRO, Kitchener MSS, 30/57 · U. Durham L., Sudan archive, Gilbert Clayton MSS

FILM

BFINA, documentary footage

SOUND

BL NSA, performance recording

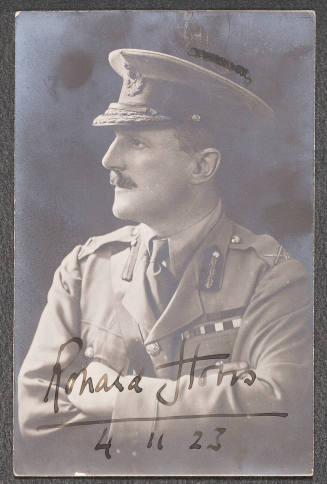

Likenesses

photograph, 1916 (with King Hussein), repro. in Storrs, Orientations, facing p. 213 · W. Stoneman, two photographs, 1919–31, NPG · J. S. Sargent, engraving, 1920, Bodl. Oxf. [see illus.] · J. Epstein, drawing, 1935, NPG · E. Kennington, drawing, repro. in Storrs, Orientations, frontispiece · J. S. Sargent, charcoal drawing, repro. in Lawrence, Seven pillars, facing p. 62 · photograph, repro. in Purcell, Cyprus, following p. 224 · photograph, repro. in Storrs, Orientations, facing p. 560 · photograph (as elderly man), repro. in Lawrence, Seven pillars, following p. 352 · photograph, repro. in The Times (2 Nov 1955)

Wealth at death

£57,869 17s. 9d.: probate, 21 Jan 1956, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Ritchie Ovendale, ‘Storrs, Sir Ronald Henry Amherst (1881–1955)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/36326, accessed 6 Aug 2013]

Sir Ronald Henry Amherst Storrs (1881–1955): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36326