Dorothy Whitney Straight

Straight, Dorothy Payne Whitney (23 Jan. 1887-13 Dec. 1968), publisher, educator, and philanthropist, was born in Washington, D.C., the daughter of Flora Payne and William C. Whitney, then secretary of the navy. Her father had added a fortune made in urban railways to his wife's dowry and with other socially prominent New Yorkers founded the Metropolitan Opera. Dorothy therefore enjoyed a materially and culturally rich childhood, whose comfort was marred by the death of her mother when Dorothy was six and of her father when she was seventeen. She then came into her own fortune and the temporary custody of her brother Harry Payne Whitney and his wife Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, who sponsored Dorothy's debut but otherwise left her mainly to herself. For part of each year she traveled in Europe with a governess and a companion, visiting cathedrals and reading books. When she was in Manhattan, she filled her free time with meetings of women's clubs and charitable societies. After graduating from the Spence School, she took classes at Columbia University. She also saw suitors but took few of them seriously. As an orphan with her own money she enjoyed greater freedom than her peers. Little pressured to marry, she took up a variety of political causes, some traditional (like charities for children) and some less so (like woman suffrage). As an officer of the New York Junior League (a charitable society of women) she guided members toward greater community involvement, leading the society to provide clean tenement housing for working single women.

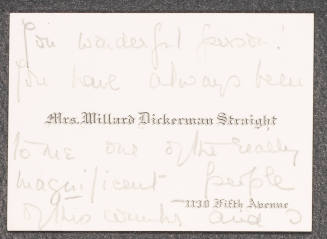

In 1905 she met Willard Straight at the house of her friend and his love-interest, Mary Harriman. Mary's father, E. H. Harriman, the railroad magnate, and Straight, a sometime diplomat and representative of American commercial interests, were working to build railroads in China. Straight came from Oswego, New York, went to Cornell, and was on his way up in Wall Street by virtue of his energy and intelligence, but he was not of the social class of Harrimans or Whitneys. Harriman kept him as a business agent but rejected him as a son-in-law. In 1909 Straight began courting Dorothy Whitney, who, unlike Mary Harriman, had no parents to keep her from him. In 1911 they married amid whispers that Straight was a fortune hunter.

As it turned out Dorothy Whitney Straight was fortunate in being able to make her own decision. Willard Straight was a good husband who shared her interests. Both were friends of once and would-be future president Theodore Roosevelt, and both supported him on the Progressive ticket in 1912. She continued to work for woman suffrage, sharing platforms with Carrie Chapman Catt and marching in parades. She persuaded her husband to speak for woman suffrage at the all-women Colony Club.

After reading Herbert Croly's 1909 book The Promise of American Life, the Straights invited him to visit them. They shared his belief that reformers must continuously press for political and social change that would tend toward more democratic government and more even distribution of wealth. Believing that a national journal could mobilize its readers to push politicians toward reforms of labor, commercial, industrial, and foreign policies, Dorothy Straight offered to underwrite such a magazine edited by Croly. The New Republic began appearing in 1914, featuring articles by Croly, Walter Lippmann, John Dewey, Learned Hand, Randolph Bourne, and Charles Beard. Willard Straight played the role of publisher and attended editorial meetings, but Dorothy Straight critiqued each issue as it appeared and suggested comments her husband might make. At least once when the magazine was ignoring an issue on which she felt strongly--in this case a campaign of slander against the New York City commissioner of charities, whom she supported--she asked Croly to lunch and persuaded him to cover the matter. As the New Republic matured, it became more independent of the Straights, but they stood by it even when Theodore Roosevelt attacked it for its radicalism.

When the United States entered the First World War, both Straights volunteered to serve. Dorothy became chair of several committees, chief among them the Council of Women's Organizations, a clearinghouse meant to coordinate the activities of women's volunteer groups. Willard became a major in the army. He survived the war, but not the peace: he died in the influenza epidemic of 1919 while attached to the U.S. delegation at Versailles.

Bereft, Dorothy slowly returned to her life. She reared her three children and attended to reform projects, including the New School for Social Research, which grew out of the New Republic, extending the magazine's project to, in one ally's words, "educate the educated." She helped to organize a national association of Junior Leagues and served as its first president. She continued to push Junior Leaguers toward more political activities, like disarmament. She drew criticism from some league members who, like many Americans in the postwar era, had tired of reform.

In 1925 she married an Englishman, Leonard Elmhirst, an agricultural economist whom she met at Cornell while planning a memorial for her husband. Like Willard Straight, Elmhirst had energy and big ideas (he was a friend of Indian reformer Rabindranath Tagore) and was slightly below her class: he thought her "too damnably rich." They moved to England and bought Dartington Hall, a Devonshire castle, which they transformed into an experimental school. The curriculum would grow from students' interests. Pupils would learn by doing and would be citizens of a self-governing and, with farming and handiwork, partly self-sustaining community.

The Elmhirsts ran the school themselves, teaching and administering until 1930, when they brought in a headmaster who made the school a little less experimental and significantly more prosperous. They had by then two children of their own. Dartington became, under the Elmhirsts' supervision, a thriving arts community. Dorothy continued to publish the New Republic until she gave up her U.S. citizenship in 1936 and put money for the journal in trust. She saw her lifelong reform efforts not as political maneuvering but as work, as she put it, "to make of our social life the rich product of a work of art." The institutions she built became important parts of the liberal political communities in the United States and Britain. She remained active in the affairs of the school she created. She died at Dartington Hall.

Bibliography

The bulk of Dorothy Whitney Straight Elmhirst's papers are in the Kroch Library of Cornell University, along with those of her husband Willard and her son Michael. The Willard and Dorothy Straight Papers are available on microfilm. Many papers relating to her later life are at Dartington Hall. The New York Public Library contains a run of the Junior League Bulletin. W. A. Swanberg, Whitney Father, Whitney Heiress (1980), discusses her earlier life in relation to her father. Michael Young, Elmhirsts of Dartington Hall (1982), focuses on her later life. Leonard Knight Elmhirst's little memoir The Straight and Its Origin (1975) is useful, as is Michael Straight's After Long Silence (1983). Louis Auchincloss, The Vanderbilt Era (1989), considers her first marriage in relation to the arranged marriages of her peers. Alvin Johnson's autobiography Pioneer's Progress (1952) is a participant's account of the early years at the New Republic and the New School for Social Research.

Eric Rauchway

Back to the top

Citation:

Eric Rauchway. "Straight, Dorothy Payne Whitney";

http://www.anb.org/articles/15/15-00956.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Tue Aug 06 2013 11:20:39 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.