William Howard Taft

Taft, William Howard (15 Sept. 1857-8 Mar. 1930), twenty-seventh president of the United States and chief justice of the United States, was born in Cincinnati, Ohio. He was the son of Alphonso Taft, U.S. secretary of war and attorney general in the Ulysses S. Grant administration, and his second wife, Louisa Maria Torrey. Taft attended Yale University, from which he graduated second in his class in 1878.

Becoming a lawyer was a natural next step for Taft, and he studied at the Cincinnati Law School where he graduated with the class of 1880. Admitted to the bar in Ohio, he combined politics with his practice. He campaigned for Republican candidates during the election of 1880 and served briefly as an assistant prosecuting attorney for Hamilton County. He was named collector of internal revenue in 1882, but resigned after a few months in the position. He was active in the 1884 campaign, speaking for James G. Blaine and acting as an election supervisor in Cincinnati. In June 1886 he married Helen Herron (Helen Herron Taft) of Cincinnati. They had three children, one of whom--Robert Alphonso Taft--became a U.S. senator.

In 1887 Governor Joseph B. Foraker named Taft to the superior court of Ohio. He won election to a five-year term in 1888. On the bench he wrote at least one opinion about a labor boycott that gave him a reputation as an anti-union judge. While still in his early thirties, he was mentioned for the U.S. Supreme Court. Taft was named solicitor general by President Benjamin Harrison (1833-1901) in February 1890. After a year in the post, where he won fifteen of the eighteen cases he argued before the Supreme Court, he was appointed to the federal circuit for the Sixth District, where he served from March 1892 until 1900.

During his years as a federal judge, Taft wrote a number of opinions in labor cases that evoked criticisms from labor unions when he ran for president. But while Taft shared the fears about social unrest that dominated the middle classes during the 1890s, he was not as conservative as his critics believed. He supported the right of labor to organize and strike, and he ruled against employers in several negligence cases. In the Addyston Pipe case (1898), Taft ruled against a combination of cast-iron pipe manufacturers in a manner that anticipated his support for the Sherman Antitrust Act when he became president.

Early in 1900 President William McKinley asked Taft to serve as the president of the Philippine Commission and "to go there and establish civil government." Taft spent nearly four years in the Philippines and became civil governor there in July 1901. The assignment revealed his talents as an administrator, and he demonstrated a fairness and lack of prejudice toward the Filipinos, though he did not believe they should have more than a limited amount of self-government. In 1902 he helped to negotiate with the Roman Catholic church an equitable solution to the complex problem of the lands that Catholic friars had owned in the islands. His tenure in the Philippines produced material improvement of living conditions in the archipelago, and he remained interested in the well-being of the Filipinos during the rest of his career.

With Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) as president after September 1901, Taft received two offers to leave the Philippines to become a justice of the Supreme Court. He declined both invitations but agreed to become Roosevelt's secretary of war in 1904. The president and the cabinet officer worked effectively during the following four years. Roosevelt sent Taft on a number of sensitive missions and often told the press that he could relax when he was away from Washington because Taft was "sitting on the lid." Taft played a role in the construction of the Panama Canal, in the response to revolutionary unrest in Cuba in 1906, and in the shaping of Far Eastern diplomacy. This collaboration increased the apparently warm feelings between Taft and Roosevelt as the election of 1908 approached.

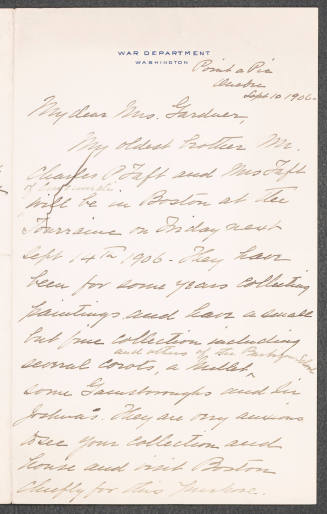

Since Roosevelt had said that he would not run in 1908, Taft's name was mentioned as his successor frequently during 1905 and 1906. Taft would have preferred an appointment as chief justice, and Helen Taft was more ambitious for the presidency than he was. Nonetheless, Taft did wish to become president, and he emerged as Roosevelt's designated successor during 1907 and 1908. Despite some personal reservations about the wisdom of the protective tariff policies of the Republicans, Taft gained a majority of delegates to the Republican National Convention. Financial help from his half brother, Charles Phelps Taft, underwrote the campaign. He was nominated on the first ballot, and James S. Sherman, a conservative congressman from New York, became his running mate. Taft campaigned effectively against his Democratic opponent, William Jennings Bryan, and won the contest with an electoral vote of 321 to Bryan's 162. He told Roosevelt that "you and my brother Charlie made that possible which in all probability would not have occurred otherwise."

The process of choosing a cabinet produced the first signs of an emerging quarrel between Taft and Roosevelt. The president-elect decided not to retain several of the members of Roosevelt's cabinet, and those that he did keep were not identified with the outgoing president's reform policies. For his own cabinet, Taft chose several corporate lawyers, including Philander C. Knox as secretary of state and George W. Wickersham as attorney general. By the time that Taft took office on 4 March 1909, coolness marked his relations with Roosevelt.

The public saw in Taft a large, genial president whose weight sometimes reached 300 pounds. He had a strong ability to judge character when his emotions were not at stake. Although inclined sometimes to procrastinate, Taft usually worked hard at his job. He was less successful in public relations. His handling of the press was inept, he traveled often for the sake of travel, and his pleasure in golf made him seem distant from his fellow citizens. He carried grudges; Theodore Roosevelt was quoted as once calling him "one of the best haters he had ever known." (Taft and Roosevelt: The Intimate Letters of Archie Butt, Military Aide, vol. 1 [1930]). A journalist said that Taft's "bump of politics" was "a deep hole." A serious illness that afflicted Taft's wife during the spring of 1909 took much of the personal gratification out of being in the White House.

In contrast to Roosevelt's expansive view of presidential power, Taft believed that the chief executive should not interpret the constitutional powers of his office too broadly. But he also saw his political task as extending and completing the regulatory program that Roosevelt had begun. These premises meant that Taft was not receptive to the use of presidential power in the areas of conservation and regulation in the ways that Roosevelt had made famous. As Roosevelt moved toward reform, Taft found himself aligned more with the Republican conservatives.

The Republican platform in 1908 had called for revision of the protective tariff. Taft called Congress into special session to deal with the subject. He had already decided not to endorse efforts to oust Speaker of the House Joseph G. Cannon, whom reform-minded "progressive" Republicans had attacked. The House passed a tariff bill that Taft could support. In the Senate, however, the Republican leader, Nelson W. Aldrich, made concessions to eastern protectionists and western backers of a tariff on cattle hides in order to find a majority for the bill. Progressive Republicans wanted Taft to denounce Aldrich. He declined to do so and sought improvements in the bill when it was in a House-Senate conference committee. The president decided that the resulting law merited his endorsement. The middle western progressives, including Robert M. La Follette (1855-1925) of Wisconsin and Jonathan P. Dolliver of Iowa, were outraged, but Taft believed that the Payne-Aldrich Tariff was the best that could be obtained. He went even further than that in a speech at Winona, Minnesota, on 17 September 1909, when he called the measure "the best tariff bill that the Republican party ever passed." Progressives talked of an anti-Taft candidate in 1912.

Even more ominous for Taft in a political sense was the quarrel that developed over conservation, the policy that Theodore Roosevelt had most warmly advanced. The secretary of the interior, Richard Achilles Ballinger, became involved in a dispute over Alaska coal lands with Gifford Pinchot, the chief forester and a close ally of Roosevelt. Taft sided with Ballinger in the quarrel and fired Pinchot in early 1910. Theodore Roosevelt began to question his selection of Taft as his successor.

Despite these political troubles, Taft's presidency saw a good deal of constructive achievement, including the Mann-Elkins Act to regulate railroads (1910), vigorous enforcement of the antitrust laws, and a program to increase governmental efficiency. In foreign policy he and Knox pursued what came to be called "Dollar Diplomacy" in Latin America and Asia. He encouraged American bankers and industry to invest in those regions, expecting this to lead to the establishment of stable governments there. Another foreign policy venture, a reciprocal trade agreement with Canada, went through the U.S. Congress only to have the Canadian voters overturn their government on the issue.

Despite his efforts to keep the Republican party together, Taft could not prevent the party's losses in the 1910 elections. The Democrats regained control of the House and cut the Republican majority in the Senate. Theodore Roosevelt had returned from an African hunting trip and advocated his "New Nationalism" in speeches during the campaign. The quarrel between the two leaders intensified. After the election they reached an uneasy truce, but their personal relations deteriorated as 1912 approached. Taft supported international arbitration treaties that Roosevelt opposed. Roosevelt called his former friend "a flubdub with a streak of the second rate and the common in him." The decisive moment came in late October 1911 when the Justice Department filed an antitrust suit against United States Steel. The bill of indictment accused Roosevelt of errors in his handling of the panic of 1907. Taft had not seen the document before it was released, but he paid the political price. An outraged Roosevelt told friends that he might enter the race against Taft in 1912. Pressure quickly mounted for him to do so. By early 1912 his hat was in the ring. However, the policies that Roosevelt espoused, including the authorization for voters to overturn state judicial decisions that they disliked, turned Republican conservatives against him.

By this time Taft believed that Roosevelt's philosophy of presidential power was fundamentally wrong, and that it was necessary to oppose him in the interest of constitutional government. The campaign that followed was bitterly contested. "I was a man of straw," said Taft during one primary, "but I have been a man of straw long enough." Roosevelt won a number of presidential primaries; Taft used his political strength in states where the party regulars determined the delegates to the national convention. As the convention in Chicago neared, the issue turned on contested delegations from southern states. The Republican National Committee, controlled by the president's forces, decided that 235 seats belonged to Taft. Roosevelt cried fraud and bolted the party.

Taft was then nominated on the first ballot, but it was an empty victory. Vice President Sherman was also renominated, but he died before the election. Nicholas Murray Butler replaced him as Taft's running mate. Later that summer Roosevelt organized the Progressive party and launched his candidacy. The Republican party was in disarray.

In the presidential race against Roosevelt and the Democratic candidate, Woodrow Wilson, Taft followed the custom that incumbent presidents did not campaign for reelection. It would not have mattered what he did. With the Republican party out of money, and their normal vote split between Roosevelt and Taft, a Democratic triumph was inevitable. Taft carried Vermont and Utah, for eight electoral votes. He finished behind Wilson and Roosevelt in the popular vote as well.

Taft accepted defeat gracefully. From 1913 to 1921 he was the Kent Professor of Constitutional Law at Yale. He also wrote extensively and lectured on the presidency. His book Our Chief Magistrate and His Powers (1916) set out his views about the extent of presidential authority. He also was a joint chairman of the National War Labor Board. His most enthusiastic commitment was to the League to Enforce Peace, an organization that lobbied for a League of Nations between 1916 and 1919. Taft became an important participant in the unsuccessful political struggle to ratify the Versailles Treaty and to ensure United States membership in the League of Nations.

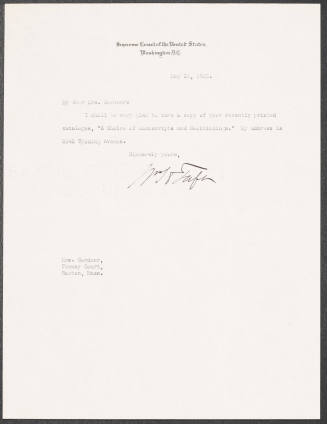

Taft never lost his desire to serve on the Supreme Court, and the election of a Republican president, Warren G. Harding, in 1920 gave him his chance. The president nominated him in June 1921, and the Senate confirmed him as chief justice of the United States with only four negative votes. Taft was in his element on the Court. He presided effectively over its deliberations and improved the way that the Court did its work. He persuaded Congress to establish a conference of the senior judges of the various circuits that the chief justice headed. The change promoted coordination of the judicial system. Enactment of the Judges Bill in February 1925 increased the ability of the Supreme Court to decide which cases it wished to hear. Taft also supervised the construction of the building in which the Supreme Court functioned after his term.

Taft's judicial record reflected his conservatism. He wrote the majority opinion in Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Company (1922), which overturned the law that taxed products made with child labor in interstate commerce. Taft argued that such use of the taxing power would "completely wipe out the sovereignty of the States." He also ruled that a labor union could be sued under antitrust laws and its funds seized when it committed illegal acts during a strike in United Mine Workers of America v. Coronado Coal Co. (1922).

The chief justice dissented when his colleagues invalidated a law setting a minimum wage for women in the District of Columbia in Adkins v. Children's Hospital (1923). He also upheld the power of the federal government to regulate interstate commerce in the case of Stafford v. Wallace (1922), and he endorsed the power of the president to fire members of the executive branch in Myers v. United States (1926).

By early 1930, Taft's health was failing; he retired from the Court on 3 February 1930. He died in Washington, D.C. Taft's presidency was not a political success, and he has been regarded as a failure between the more impressive administrations of Roosevelt and Wilson. Toward the end of the twentieth century, Taft's concern with the legal limits of his office was regarded with greater respect in light of the growing potential for abuse of presidential power. The actual record of progressive reform measures he achieved is more impressive than it seemed to his contemporaries. More of a judge than a popular leader, Taft was happiest during the years that he served as chief justice. The only person to hold both of these offices in the nation's history, Taft served the United States with efficiency and achievement during his impressive public career.

Bibliography

Taft's personal papers are at the Library of Congress and have been microfilmed. It is a large and well-organized collection. The Theodore Roosevelt, Elihu Root, and Woodrow Wilson papers at the Library of Congress have relevant materials on Taft. The Charles D. Hilles papers at Yale University contain the political files of Taft's presidential secretary. Taft's own writings are quite extensive. Among them, Present Day Problems (1908) is a collection of speeches and remarks during his race for the White House; Presidential Addresses and State Papers (1910) covers the early part of his presidency. Helen Herron Taft, Recollections of Full Years (1914), is a memoir by Mrs. Taft. The best biography is Henry F. Pringle, The Life and Times of William Howard Taft (2 vols., 1939). Ishbel Ross, An American Family: The Tafts, 1678-1964 (1964), provides an overview of the Taft clan. Paolo E. Coletta, The Presidency of William Howard Taft (1973), examines Taft's record in the White House, as do Walter Scholes and Marie V. Scholes in The Foreign Policies of the Taft Administration (1970). Other interpretations of Taft as president are Donald F. Anderson, William Howard Taft: A Conservative's Conception of the Presidency (1973), and Judith Icke Anderson, William Howard Taft: An Intimate History (1981). Frederick C. Hicks, William Howard Taft: Yale Professor of Law and New Haven Citizen (1945), and Alpheus T. Mason, William Howard Taft: Chief Justice (1965), are studies, respectively, of Taft's political retirement and then his service as chief justice of the United States.

Lewis L. Gould

Back to the top

Citation:

Lewis L. Gould. "Taft, William Howard";

http://www.anb.org/articles/06/06-00642.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Tue Aug 06 2013 11:26:05 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.