Daniel Berkeley Updike

Updike, Daniel Berkeley (24 Feb. 1860-29 Dec. 1941), book designer and printer, was born in Providence, Rhode Island, the son of Caesar Augustus Updike, a lawyer and state representative, and Elisabeth Bigelow Adams. Updike was an only child born into an old and well-connected New England family, but his father's death in 1877, when Updike was seventeen, prevented his going beyond grammar school in his formal education. Updike's intellectual and cultural character, however, was molded by his mother, an antiquary and scholar of French and English literature. Updike also came from an Episcopalian background, and his religion greatly influenced both his character and his later work as a printer.

Updike's first book-related job was as a temporary volunteer in the library of the Providence Athenaeum. Then, in 1880 Updike was offered a job, through the influence of a cousin, as an errand boy at Houghton, Mifflin & Company of Boston, Massachusetts. He worked at the firm for twelve years, moving up to the advertising department, where he prepared copy. Updike quickly began to direct how copy might be set up, inspired as always by a personal love of order. In his last two years with the firm, he was transferred to its Riverside Press at Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he learned about the mechanics of printing and displayed an aptitude for designing books.

During his years with Houghton, Mifflin, Updike took two leaves of absence, which he spent with his mother in Europe. These visits served to broaden his aesthetic background. While he was still working for the Boston publisher, he completed a book project with the intellectual and financial assistance of Harold Brown, a friend from childhood. The two, who shared a devout interest in the rituals of the Episcopal church, compiled On the Dedications of American Churches, which Updike also designed and saw through the Riverside Press in 1891.

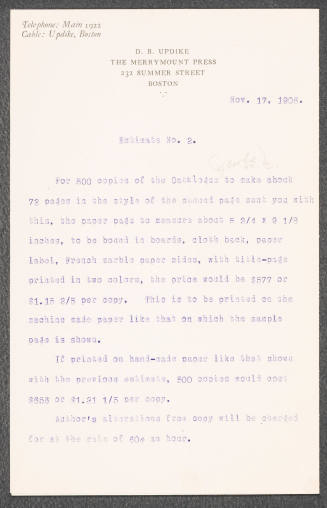

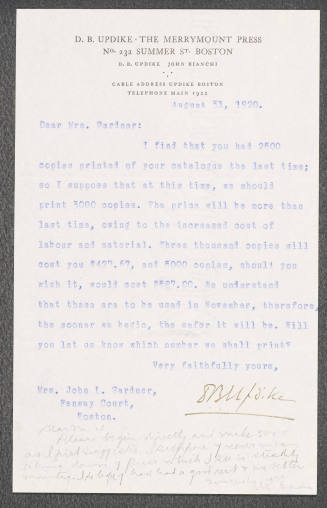

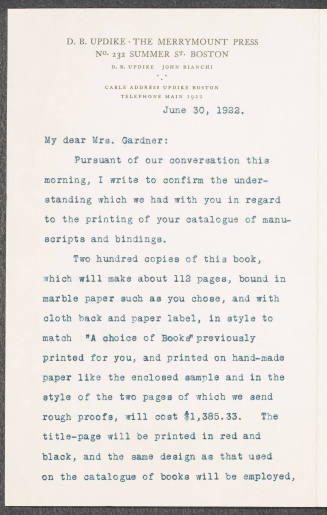

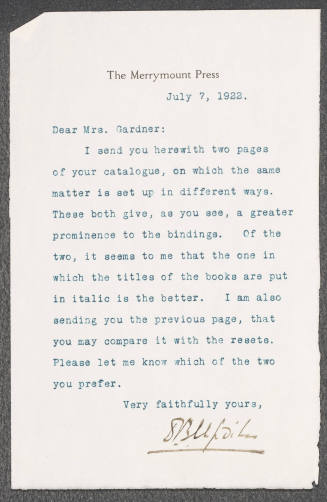

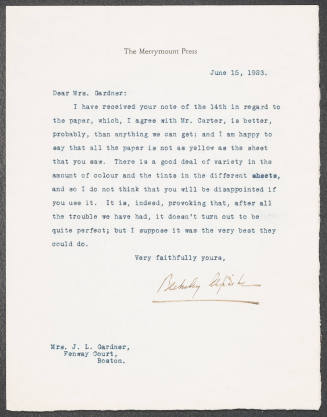

Updike decided to leave Houghton, Mifflin in 1893. That same year he founded the Merrymount Press, although that imprint did not appear formally on a book of his until 1896. The name of the press, which Updike himself explained, suggested "that one could work hard and have a good time" (Notes, p. 56). Although Updike moved the press around the Boston area over the course of about thirty years to accommodate its expanding business, employees, and equipment, he finally settled it at 712 Beacon Street.

Early in his career, and once again with the financial support of Harold Brown, Updike designed a monumental work--the Episcopal Altar Book--begun in 1893 and completed in 1896. He had architect Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue create the typeface, the ornate initials, and the decorative borders for the book. Likewise, Updike had printer Theodore Low DeVinne do the presswork, since Updike's Merrymount Press had not yet obtained the required equipment. The Altar Book was reminiscent of William Morris's Kelmscott Press style, but as Updike developed as a book designer and printer, he would abandon the style of the "revival-of-printing" movement, which had been inspired by Morris's beautifully printed books of the late nineteenth century, favoring instead legibility over ornamentation.

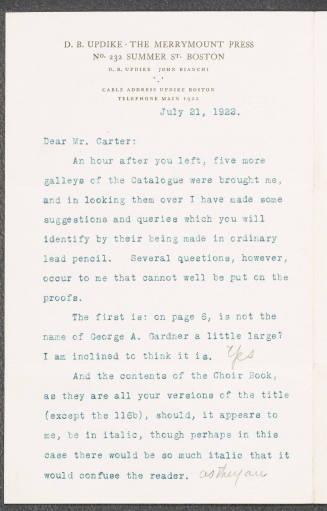

Updike continued to foster the growth of his business by adding to his knowledge of printing. In 1896 he chose John Bianchi, the brother of a former associate at the Riverside Press, to be the foreman of the Merrymount Press. Talented in his own right, Bianchi was made a full partner in 1915. Between 1896 and 1914 Updike journeyed to foreign places several times, going to printing houses such as Kelmscott and Caslon, acquiring type from foundries, examining books at the British Museum, and visiting printing centers such as Mainz, Parma, and Antwerp. He also improved his press by acquiring powered machinery, refusing to believe that high-quality books could only be handmade.

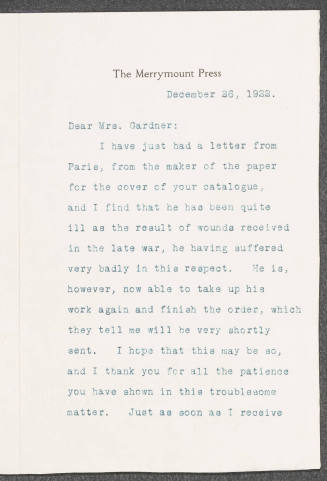

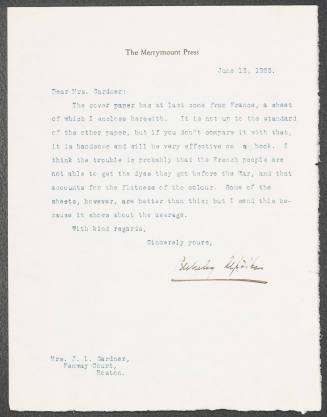

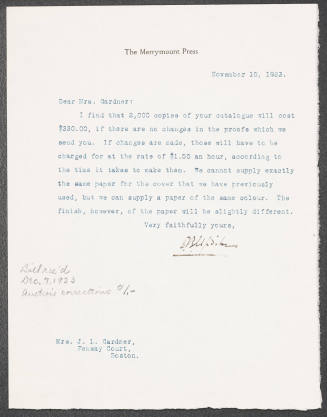

Throughout the history of Merrymount Press, Updike was supported by a clientele from his social background that requested and appreciated fine books. He also received the patronage of commercial publishers such as Thomas Y. Crowell and Scribners who asked him to design high-quality editions. Updike printed a great variety of texts, which included university catalogs, association reports, musical programs, book club keepsakes, advertisements, family histories, and serious literature. He took pains with all, believing that it was the guiding principle of his press "to do the ordinary work of its day well and suitably for the purpose for which it was intended" (Notes, p. 56). Among the serious literature bearing the imprint of Merrymount Press were various novels by Edith Wharton, printed from 1898 to 1907, and titles in "The Humanists' Library," printed from 1906 to 1914, which featured such authors as Leonardo da Vinci and Sir Philip Sidney.

In 1911 Updike was invited by the Graduate School of Business Administration at Harvard University to present a course of instruction to students of printing. For five years he gave lectures on type design and the use of type in various countries. Updike carefully recast his lectures and in 1922 published them as Printing Types: Their History, Forms and Use, an authoritative two-volume work on printing history that is still highly regarded. For his scholarship displayed in Printing Types, he was awarded an honorary master of arts by Harvard in 1929.

In 1930 Updike completed another important ecclesiastical book, his edition of the revised Book of Common Prayer, which was financed by J. P. Morgan, Jr. The prayer book, perhaps Updike's most significant achievement, reflected in its simple decoration and well-planned pages the functional style that Updike sought to achieve as a designer of books.

Updike never married. He died at his home in Boston. He was known as a scholarly printer who pursued high standards, promoted utility over decoration, and designed books by trusting his own taste and creative talent rather than yielding to the pressures of a patron. After Updike's death, Bianchi carried on the work of the Merrymount Press until 1949, when its operations ceased.

Bibliography

Updike's personal papers, correspondence, personal library, and the "Updike Collection of Books on Printing" are in the Providence Public Library. Updike wrote an autobiographical account and history of his press titled Notes on the Merrymount Press & Its Work (1934). He published his thoughts on the craft of printing in two other works besides Printing Types: In the Day's Work (1924) and Some Aspects of Printing Old and New (1941). Some letters of Updike were published in Stanley Morison & D. B. Updike: Selected Correspondence, ed. David McKitterick (1979). See also George Parker Winship, Daniel Berkeley Updike and the Merrymount Press (1947), for a critical biography. The American Institute of Graphic Arts published a collection of essays on Updike and his press written by friends and colleagues and edited by Peter Beilenson titled Updike: American Printer and His Merrymount Press (1947). An obituary is in Publishers Weekly, 3 Jan. 1942.

Charles Zarobila

Back to the top

Citation:

Charles Zarobila. "Updike, Daniel Berkeley";

http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-02294.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Tue Aug 06 2013 11:41:43 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.