William Foster Apthorp

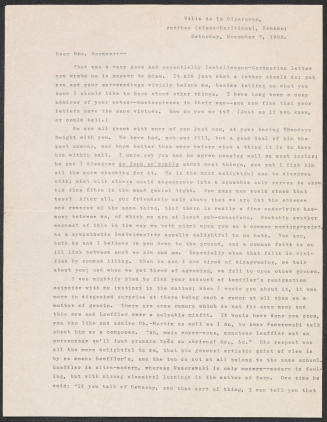

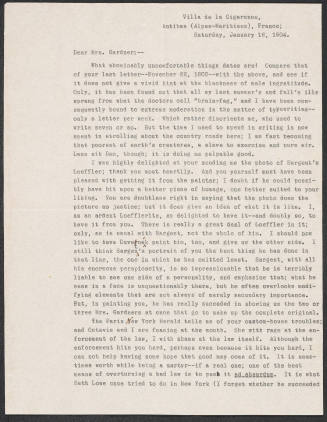

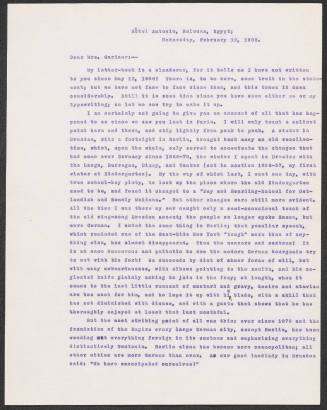

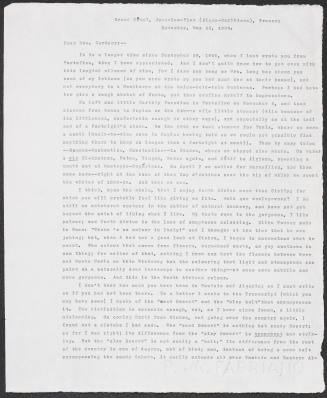

Apthorp, William Foster (24 Oct. 1848-19 Feb. 1913), music critic and writer, was born in Boston, Massachusetts, the son of Robert Apthorp and Eliza Hunt. Since before the American Revolution, Apthorp's ancestors had participated in the mercantile and intellectual life of Boston. After studying languages, art, and music for four years in France, Germany, and Italy, Apthorp returned with his family to Boston in 1860. Deciding upon a career in music rather than in art, he entered Harvard College and studied piano, theory, and counterpoint with John Knowles Paine until Paine's departure for Europe in 1867. Apthorp graduated in 1869 from Harvard College, where he had been conductor of the Pierian Sodality in his senior year. He also studied piano with B. J. Lang for several years.

Apthorp taught piano and theory at the National College of Music from 1872 to 1873, then taught piano, theory, counterpoint and fugue at the New England Conservatory from 1873 to 1886. He also held classes in aesthetics and the history of music in the College of Music of Boston University until 1886. In 1876 Apthorp married Octavie Loir Iasigi.

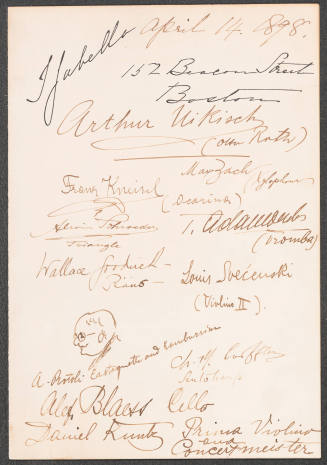

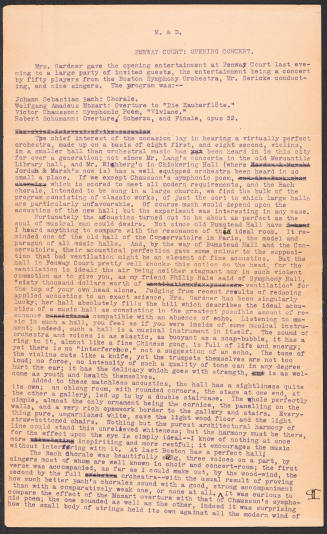

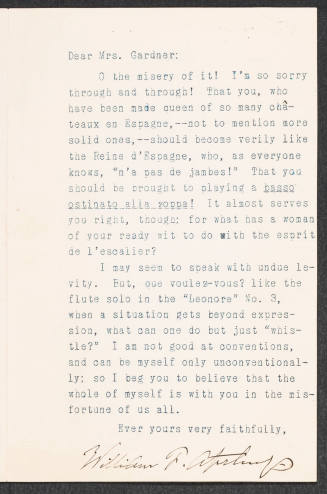

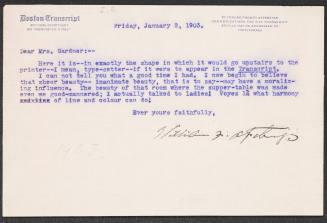

It was as music critic and writer that Apthorp achieved national distinction and influence. His most important positions in this area were as music editor and critic of the Atlantic Monthly from 1872 to 1877, music and drama critic of the Boston Evening Transcript from 1881 to 1903, and annotator and editor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra concert programs from 1892 to 1901. He also lectured in Boston, New York, and Baltimore; co-edited, with John Denison Champlin, Scribner's Cyclopedia of Music and Musicians (1888-1890); and contributed articles to diverse publications, including Dwight's Journal of Music and Scribner's Magazine. He published a prodigious body of work in books, translations, and editions from 1875 to 1903, the year of his retirement. Thereafter, he lived in Vevey, Switzerland, until his death there.

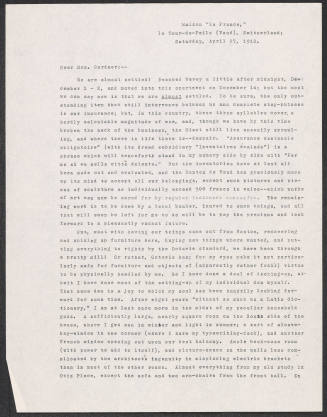

An issue of considerable cultural significance in the later nineteenth century was the extent to which European "new music" would be supported by the American public. Apthorp's writings reveal, with few exceptions, his active leadership in fostering its acceptance. He wrote perceptively not only about compositions by Bach and Beethoven, but also about the contributions of more recent and then controversial composers including Berlioz, Liszt, and Wagner. As compiler of an annotated list of Richard Wagner's published works (1875), translator of selected letters and writings of Hector Berlioz (1879), editor of the songs of Robert Franz (1903), and as an annotator who clarified the large-scale structures or instrumental resources of unfamiliar works with reference to the musical scores, Apthorp performed a vital service by disseminating to American readers source material and musically informed commentary. His broad musical knowledge and experience also enabled him to assist the cause of American music through respectful treatment of works by contemporary American composers. Apthorp's proud advocacy of the "new spirit in music" may have contributed, however, to his exaggerated view of Mendelssohn's stylistic, and John S. Dwight's later critical, conservatism.

Apthorp wrote valuable historical and descriptive notes for the Boston Symphony Orchestra Programmes from 1892 to 1901; in the "Entr'acte" section of the program books, he penned short essays of general interest, some of which were reprinted in two volumes about music and musicians entitled By the Way (1898). In one of these pieces, on form, Apthorp described his particular admiration for the organic structural principles underlying the fugue and the sonata, but he avowed an open spirit in greeting newer compositional approaches. In Musicians and Music-Lovers (1894), Apthorp explained his individual conception of the music critic's role: he was not to judge but rather "to raise the standard of musical performance and popular musical appreciation." Citing his admiration for the French style of subjective critical advocacy appearing with the critic's signature, which he called "personal criticism," Apthorp expressed his hope to "set people thinking" by mediating as interpreter between the composer, or performer, and the public. He believed that the critic's highest function should be to let the public "listen to music with his ears."

Boston's active concert life assured Apthorp of ready access to instrumental music, about which he wrote more persuasively than he did about opera. In The Opera Past and Present: An Historical Sketch (1901), Apthorp noted a connection between the dramatic aims of the Florentine Camerata and Wagner and stressed Gluck's musicodramatic individuality, but he focused too exclusively on the prominence of the supernatural in German Romanticism to the detriment of other stylistic features.

In general, Apthorp's tendency to simplify complexities, disadvantageous in his historical essays, may have been a decisive factor in furthering his successful communication with the general public. He filled a constructive critical and educational role in his era by guiding readers toward greater understanding of unfamiliar musical works. Apthorp's writings encouraged recognition in American society for art music and musicians.

Bibliography

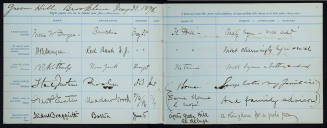

According to D. W. Krummel et al., Resources of American Music History: A Directory of Source Material from Colonial Times to World War II, Apthorp's miscellaneous letters and papers are located in the Rare Books and Manuscripts Division of the Boston Public Library and at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston; additionally, research files pertaining to a biographical study are in the collection of Joseph Mussulman. Works by Apthorp not mentioned by title in the text include "A List of the Published Works of Richard Wagner," in Art Life and Theories of Richard Wagner, selected and trans. by Edward L. Burlingame (1875); Hector Berlioz: Selections from His Letters, and Aesthetic, Humorous, and Satirical Writings, trans. with a bio. sketch by William F. Apthorp (1879); and Robert Franz, Fifty Songs, ed. William Foster Apthorp (1903). See also the entry by Richard Aldrich in The New Grove Dictionary of American Music, ed. H. Wiley Hitchcock and Stanley Sadie, vol. 1 (1986), p. 62. Obituaries are in the Boston Herald, 22 Feb. 1913, and the Boston Transcript, 20 Feb. 1913.

Ora Frishberg Saloman

Citation:

Ora Frishberg Saloman. "Apthorp, William Foster";

http://www.anb.org/articles/18/18-00031.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 10:20:08 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

William Foster Apthorp (October 24, 1848 in Boston – February 19, 1913 in Vevey, Switzerland)[1][2] was a United States writer, drama and music critic, editor and musician.

Contents

1 Biography

2 Books

3 References

4 Further reading

Biography

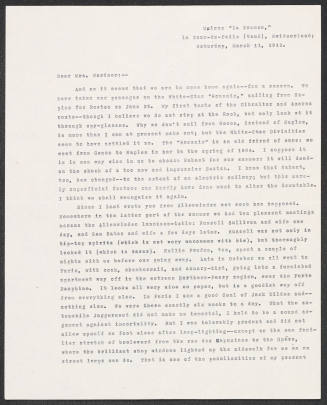

He was born in 1848. He was the "son of Robert East Apthorp and Eliza Hunt, grandson of John T. Apthorp and direct descendant of Charles Apthorp, named after his maternal great grandfather William Foster. Since before the American Revolution, Apthorp's ancestors had participated in the mercantile and intellectual life of Boston." (Saloman, Am. Nat. Biog., Vol. 13, p. 567) He graduated from Harvard in 1869 having taken musical classes with J. K. Paine. He then took piano from B. J. Lang for 7 or 8 years longer. "Coming from an old Boston family whose efforts in the cause of art have always been most intimately linked with its progress in the city, he has won a career not less worthy than any of his line." (Elson, Supplement, p. 3)[3]

In 1856, his parents took him to study languages and art in France, Dresden (Marquardt'sche Schule), Berlin (Friedrich Wilhelm'sches Progymnasium), Rome (École des Frères Chrétiens), and Florence (with classmate John Singer Sargent).[4] He developed into an accomplished linguist who could speak “all the leading languages of Europe.”[citation needed] He returned to Boston in 1860.[4] In 1869,[2] he graduated from Harvard College, where he studied piano, harmony, and counterpoint with the institution’s first professor of music, the composer John Knowles Paine. When Paine left for Europe in 1867, he took up the study of piano with B. J. Lang.[2] He studied music theory on his own.[4]

In 1872,[4] he began his career as a critic writing for the Atlantic Monthly, Dwight's Journal of Music, the Boston Courier, and the Boston Evening Traveller, and went on to help shape Boston’s musical tastes for 20 years as drama and music critic for one of Boston’s premier urban newspapers, the Boston Evening Transcript.[2] From 1892 to 1901, he was program essayist for the Boston Symphony Orchestra.[5] Apthorp also served at various times on the faculties of the National College of Music in Boston (harmony), the New England Conservatory of Music (piano, harmony, counterpoint, and theory), and the College of Music of Boston University (aesthetics and music history). He lectured at the Lowell Institute, Boston, and the Peabody Institute, Baltimore.[5]

He married Octavie Loir Iasigi in 1876. In 1903, failing eyesight prompted his retirement to Vevey, Switzerland.[4]

Books

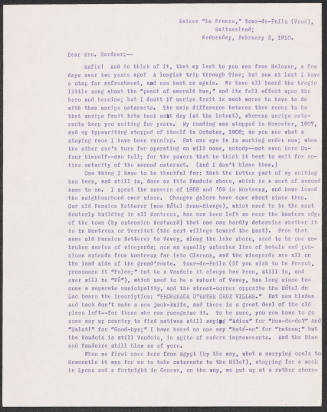

His books include:

Hector Berlioz: Selections from His Letters and Writings, with a biographical sketch (1879) A pioneer work in English on Berlioz.[5]

Aesthetic, Humorous, and Satirical Writings (1879)

Some of the Wagner Heroes and Heroines (1889)

Musicians and Music Lovers, and Other Essays (1894)

By the Way (1898)

The Opera, Past and Present: An Historical Sketch (1901)

A translation of several of Émile Zola’s stories (1895)

He also published editions of the songs of Robert Franz and Adolf Jensen, and co-edited, with John D. Champlin, Scribner’s Cyclopedia of Music and Musicians (1888–1890).

References

"Linked Authority File". March 26, 2011.

Wikisource-logo.svg Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). "Apthorp, William Foster". Encyclopedia Americana.

http://www.margaretruthvenlang.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=36&Itemid=129

Fannie L. Gwinner Cole (1929). "Apthorp, William Foster". Dictionary of American Biography. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

Wikisource-logo.svg Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Apthorp, William Foster". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

Further reading

Joseph Edgar Chamberlin, The Boston Transcript: A History of its First Hundred Years (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1930), 206

Joseph A. Mussulman, Music in the Cultured Generation, passim.; and Robert Brian Nelson, “The Commentaries and Criticisms of William Foster Apthorp,” Ph.D., University of Florida, 1991

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Foster_Apthorp I.S. 11/1/2018

The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd ed., s. v. “Apthorp, William Foster.”