Samuel Croxall

Samuel Croxall was born in Walton on Thames, where his father (also called Samuel) was vicar. He was educated at Eton and at St John's College, Cambridge, where he took his B.A. in 1711 and entered holy orders.[2] Soon after graduating he began to emerge as a political pamphleteer, taking the Whig side on the question of the Hanoverian succession. In 1713 he published An original canto of Spencer: design'd as part of his Faerie Queene, but never printed,[3] followed next year by Another original canto of Spencer.[4] Croxall's satirical target was the Tory politician of the day, Robert Harley, Earl of Oxford, and the choice of poetical model was also politically motivated. In 1706 the Whig turncoat Matthew Prior had used the Spenserian stanza in An Ode, Humbly Inscrib'd to the Queen on the conduct of the War of the Spanish Succession; at the time of Croxall's poems, Prior was negotiating an unpopular peace on behalf of Harley and so the style he had adopted was being turned against him. This was further underlined by Croxall's next political poem, An ode humbly inscrib'd to the king, occasion'd by His Majesty's most auspicious succession and arrival, once more using the Spenserian stanza and published in 1715.

As a reward for his loyal services at a time of disputed succession, Croxall was made chaplain in ordinary to King George I for the Chapel Royal at Hampton Court. Later that year he preached before the king at St Paul's Cathedral on Incendiaries no Christians (on the text of John 13.35) and came into collision with the new Prime Minister, Robert Walpole. Gossip had it that Walpole had stood in the way to some ecclesiastical dignity which Croxall wished to obtain and found himself the object of veiled references to corrupt and wicked ministers of state in the sermon. Since Walpole was a vengeful man, 'it was expected that the doctor for the offence he had given would have been removed from his chaplainship, but the court over-ruled it, as he had always manifested himself to be a zealous friend to the Hanoverian succession'.[5] Croxall continued his compliment to the king in his poem "A Vision", which places the new monarch within the context of the succession of kings and queens of England, presided over by the poets Geoffrey Chaucer and Edmund Spenser.

In 1717 Croxall married Philippa Proger, who had inherited her father's lands in Breconshire, including the family home of Gwern Vale; later he was to take up residence there from time to time.[6] During his continued stay in London he moved in the circle of the Kit-Cat Club, a grouping of Whig politicians and writers. One of their joint literary projects was the translation of the 15 books of Ovid's Metamorphoses under the editorship of Samuel Garth.[7] Among the other contributors were John Dryden, Joseph Addison, Arthur Mainwaring, Nicholas Rowe, John Gay and Laurence Eusden. Croxall's contribution was to translate the sixth book, three stories of the eighth book, one story of the tenth (the fable of Cyparissus), seven of the eleventh, and one of the thirteenth (the funeral of Memnon). As a translator of Ovid, he was still being talked of a century later in Leigh Hunt's reminiscences of Lord Byron. There he remarks of the arbitrary nature of the poet's tastes that 'It would have been impossible to persuade him that Sandys's Ovid was better than Addison's and Croxall's'.[8]

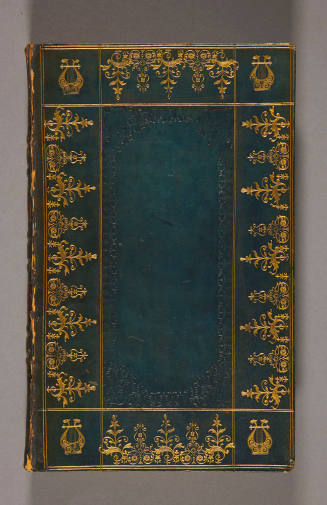

During the following years Croxall was engaged in several literary ventures on his own account. In 1720 he edited A Select Collection of Novels written by the most celebrated authors in several languages.[9] In its four volumes were eighteen complete or extracted works by such authors as Madame de la Fayette, Miguel de Cervantes, Nicolas Machiavelli, the Abbé de St. Réal, and Paul Scarron. So successful was this that he extended it to six volumes containing nine new works in 1722.[10] Further editions under different titles followed into which some English works were also introduced. But Croxall was to achieve even greater success with his other work of 1722, The Fables of Aesop and Others,[11] which were told in an easy colloquial style and followed by 'instructive applications'. Aimed at children, each fable was accompanied by illustrations which were soon to find their way onto household crockery and tiles. Several more editions were published in his lifetime and the book was continuously in print until well into the second half of the 19th century.