William Heinemann

Surbiton, Surrey, 1863 - 1920, London

Heinemann's earliest ambition was to be a professional musician, a pianist or possibly a composer, but he decided that he lacked the necessary talent to be a great artist and turned to his second love, literature. In 1879 he became an apprentice to Nicolas Trübner. At Trübners, Heinemann gained practical experience in every phase of publishing. After Trübner's death in 1884 Heinemann was largely responsible for the firm until it was sold to Charles Kegan Paul in 1889.

After leaving Trübners, Heinemann travelled on the continent and built connections with publishers in France, Germany, Scandinavia, Russia, and Italy. In 1890 he opened his own publishing firm on the second floor at 21 Bedford Street, Covent Garden. Heinemann's staff consisted of W. Ham-Smith, who had followed him from Trübners and who became the business manager, and an office boy. One year later a secretary, Miss Pugh, joined the staff.

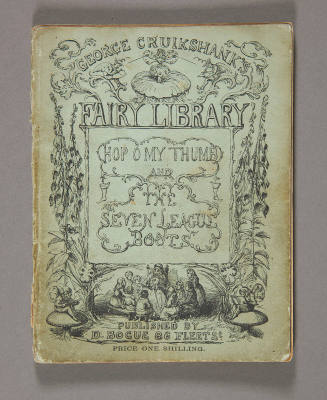

The first book published by the firm was Hall Caine's The Bondman (1890), which had been rejected by Cassell. This book had great popular success and put Heinemann on the road to fortune. Among the earliest publications was James McNeill Whistler's The Gentle Art of Making Enemies (1890). Heinemann, who was a friend of Whistler's, later published Mr and Mrs Joseph Pennell's Life of Whistler. The 1890–93 lists seem to be widely eclectic, but steadily a structure emerged, based on fiction aimed at subscription libraries, and book series such as The Great Educators, Heinemann's International Library, and Heinemann Scientific Books. Three authors contributed to the rapid establishment of Heinemanns: Frances McFall (Sarah Grand), Robert Hichens, and Thomas Beech (Henri Le Caron).

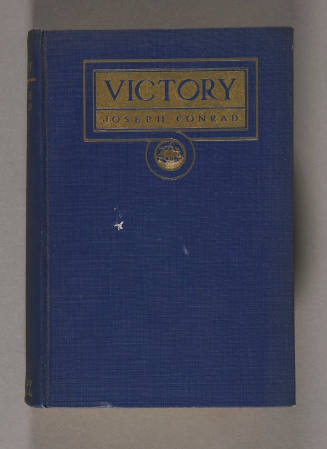

Two men in particular played substantial roles in the Heinemann firm: Edmund Gosse and Sydney Pawling. Gosse was a chief adviser, reader, editor, and author. Pawling joined the firm in 1893 as a full-time partner. In the 1890s Heinemann's fiction list included authors of the calibre of Robert Louis Stevenson, Rudyard Kipling, George Moore, Henry James, and H. G. Wells. The firm continued to attract a diverse group of skilled authors, among them E. F. Benson, John Masefield, D. H. Lawrence, Elizabeth Robbins, Mrs Dudney, Flora Annie Steel, Max Beerbohm, Joseph Conrad, William Frend de Morgan, and John Galsworthy. Between 1895 and 1897 Heinemann also published the New Review, under the editorship of W. E. Henley, and dramatic works including those of Sir Arthur Pinero, Somerset Maugham, Israel Zangwill, Henry Davies, and Charles Haddon Chambers. Heinemann's own plays—The First Step (1895), Summer Moths (1898), and War (1901)—were published by John Lane. On 22 February 1899 he married Magda Sindici, a young Italian author; he had published her first novel, Via lucis (1898), written under the pseudonym Kassandra Vivaria.

Although not all of Heinemann's authors were of the first rank, many became pillars of the firm's backlist, which was an essential ingredient for long-term prosperity. During his lifetime Heinemann's list came to include art books and books of exploration, medicine, and science. The Loeb Classical Library was published by the firm until 1988, when it was sold to Harvard University Press.

Heinemann's European connections, coupled with the advice and editorial expertise of Edmund Gosse, were reflected in the regular commissioning of translations of work by European authors. Stendhal, Victor Hugo, Flaubert, Daudet, Jules and Edmund de Goncourt, Goethe, Ibsen, and Björnstjerne Björnson were some of the authors included on the list. Another enduring contribution that Heinemann made to the British reading public was the commissioning of the translations of the Russian novelists Goncharov, Tolstoy, Turgenev, Dostoyevsky, and others by Constance Garnett, wife of the publisher's reader, Edward Garnett.

Throughout most of his professional life Heinemann had brushes with the Society of Authors, and he opposed the emergence of literary agents. Despite his opposition, however, Heinemann became one of London's most respected publishers, exerting considerable influence on the industry. He played a great part in founding the Publishers' Association of Great Britain and Ireland in 1896, and was president of the association from 1909 to 1911. From 1896 to 1913 he was the British representative on the international commission and executive committee of the International Congress of Publishers; it was largely due to his initiative that the congress came into existence. Through the congress, Heinemann played a leading role in the protection of international copyrights and he influenced the American Copyright Bill of 1909. After his resignation from the congress in 1913 and until his death in 1920 Heinemann was president of the Associated Booksellers of Great Britain and Ireland.

Heinemann's death was sudden and unexpected. On 5 October 1920, when his valet, George Payne, went to call him at half past eight in the morning at his home, 32 Lower Belgrave Street, London, he found him lying dead on the floor by his bed. At the inquest, his doctor said that he had been suffering from a chronic nervous disease, which eventually would have made him blind; the cause of death was a heart attack.

Heinemann's death provoked a crisis for his publishing firm. His marriage, which had ended in divorce in 1905, had produced no children, and his nephew John Heinemann, whom Heinemann had intended as his successor, had been killed in the First World War. Sydney Pawling, his business partner of twenty-seven years, could not afford to buy Heinemann's 55 per cent share of the firm. Liquidation of the company or its absorption by a rival was averted when the New York publisher F. N. Doubleday agreed to Pawling's plea that he buy a controlling interest in the firm and leave the company intact.

At his death Heinemann's estate was valued at £33,780 with a net worth of £32,578. He left £500 to the Publishers' Association as a reserve fund to meet any emergencies where the interests of British publishers were threatened; £500 went to the National Book Trade Benevolent Fund, of which he had been president. Sydney Pawling inherited his personal papers. Subject to the life of his mother and his two sisters, half of his residuary estate went to the Royal Society of Literature to establish the Heinemann Foundation of Literature, which was to give a prize of up to £200 for a work of worth. Although fiction was not excluded, Heinemann's intention was to reward classes of literature that were less remunerative—namely poetry, criticism, biography, and history. This prize continues to be awarded regularly.

Linda Marie Fritschner

Sources

‘Death of Mr Heinemann’, The Times (6 Oct 1920), 13 · L. Griest, Mudie's Circulating Library and the Victorian novel (1970) · W. Heinemann, The hardships of publishing (1893) · A. Hill, In pursuit of publishing (1988) · M. S. Howard, Jonathan Cape: publisher (1974) · ‘International Publishers' Congress: the Copyright Convention’, The Times (17 June 1913), 7 · ‘Literature gifts endowment’, New York Times (14 Oct 1920), 12 · J. London, ‘London book talk’, New York Times Book Review (20 Oct 1920), 19 [obit.] · V. Menkes, ‘William Heinemann’, British Book News (Oct 1989), 688–92 · ‘Scholarship fund for literature’, The Times (12 Oct 1920), 10 · J. St John, William Heinemann: a century of publishing (1990) · F. Warburg, All authors are equal (1973) · F. Whyte, William Heinemann: a memoir (1928) · CGPLA Eng. & Wales (1920)

Archives

Heinemann Ltd, London, archive · Hunt. L., letters · Iowa University Libraries · National Library of Canada, Ottawa · Newcastle Central Library · Stanford University Library, California :: BL, corresp. with Lord Northcliffe, Add. MS 62174 · NYPL, Berg collection · Richmond Local Studies Library, London, corresp. with Douglas Sladen

Likenesses

G. C. Beresford, photograph, 1920, Heinemann Ltd, London [see illus.] · photographs, Heinemann Ltd, London

Wealth at death

£33,780 19s. 4d.: probate, 12 Nov 1920, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Linda Marie Fritschner, ‘Heinemann, William Henry (1863–1920)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2009 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2113/view/article/33800, accessed 8 Aug 2013]

William Henry Heinemann (1863–1920): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33800

[Previous version of this biography available here: September 2004]

William Heinemann (18 May 1863 – 5 October 1920) was the founder of the Heinemann publishing house in London.

Heinemann was born in 1863, in Surbiton, Surrey. In his early life he wanted to be a musician, either as a performer or a composer, but, realising that he lacked the ability to be successful in that field, he took a job with the music publishing company of Nicolas Trübner.[1] When Trübner died, Heinemann founded his own publishing house in Covent Garden in 1890. The company published many translations of the classics Great Britain, as well as such authors as H. G. Wells, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Rudyard Kipling.[1]

William Heinemann died in London unexpectedly on 5 October 1920.[2] He had no children and his presumptive heir, his nephew John Heinemann, had died in the First World War. Heinemann's share of the company was bought out by Frank Nelson Doubleday, the New York publisher.[1]

He bequeathed funds to the Royal Society of Literature to establish a literary prize, the W. H. Heinemann Award, given from 1945 to 2003.[1]

Notes[edit]

^ Jump up to: a b c d Fritschner, Linda Marie (2004). "Heinemann, William (1863–1920)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

Jump up ^ Hall Caine: Portrait of a Victorian Romancer by Vivian Allen, Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1997, pp.373-384 (Wikipedia)

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated9/5/24

Partick, Scotland, 1872 - 1948, Monte Carlo

Berdychiv, Ukraine, 1857 - 1924, Bishopsbourne, England

Philadelphia, 1855 - 1936, New York

London, 1809 - 1885, Vichy

Pesitza, Hungary, 1867 - 1935, Vevey, Switzerland

Speldhurst, England, 1864 - 1950, Zurich Switzerland

British, 1864 - 1912

Schleinitz, present day Unterkaka, 1816 - 1895, Leipzig