Richard Bentley

active London, 1829 - 1898

LC Heading: Richard Bentley (Firm)

LC name authority rec.: n79018629

LC Heading: Richard Bentley and Son

found: MWA/NAIP files (hdg.: Richard Bentley (Firm); variant: R. Bentley; note: London publishing firm; 1829-32 firm known as Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley; located in Great Marlborough St. and later New Burlington St.; later name Richard Bentley and Son)

Biography:

Bentley, Richard (1794–1871), printer and publisher, was born near Fleet Street in London on 24 October 1794, the youngest but one of the children of Edward Bentley (b. 1753), publisher and principal of the accountant's office in the Bank of England, and Anne Nichols, daughter of a confectioner living opposite Islington church. Though not related to seventeenth- and eighteenth-century publishers with the same surname, Bentley grew up from the cradle among printers, publishers, and authors. His father and maternal uncle John Nichols (1745–1826) jointly owned and published the General Evening Post; Nichols also published and wrote for the Gentleman's Magazine and composed antiquarian compilations. From 1803 Bentley attended St Paul's School, where he became close friends with Richard Harris Barham, later minor canon of St Paul's Cathedral, author under the pen-name Thomas Ingoldsby, and Bentley's literary adviser.

After leaving school Bentley worked for a time in his uncle's Red Lion Court office, learning the craft and business of printing. Then in 1819 he joined with his older brother Samuel Bentley (1785–1868) in a printing business, located first in Dorset Street, Salisbury Square, and afterwards in Shoe Lane. This firm, the first to pay artistic attention to wood-engraved illustrations, became arguably the finest printers in London. Established in business, Bentley married Charlotte, daughter of Thomas Botten; their eldest surviving son was George Bentley (1828–1895), afterwards his father's partner and successor.

Henry Colburn, an opportunistic and unscrupulous publisher, had the Bentley firm produce his books; by the late 1820s his printing bill was running at more than £3000 annually, and he was about to dispose of his business. To protect the firm's investment, Richard agreed on 31 August 1829 to sell his interest in the printing business to his brother, and by the terms of an agreement on 3 June 1829 to become Colburn's partner. Bentley brought £2500, took ‘upon himself all the active part of the business’, and was to receive two-fifths of the profits, while Colburn, reserving to himself certain properties, brought the rest of his investments and copyrights and was to receive three-fifths of the profits, guaranteed to be at least £10,000.

From the beginning the partners' working relationship soured; among other causes of friction, according to his office manager, Edward Morgan, Colburn's accounts were so ‘carelessly kept’ (Morgan), that it took over two years to ascertain a balance. Meanwhile Colburn and Bentley launched four series of books: a National Library of General Knowledge (25 August 1830–29 February 1831), which failed after 55,750 copies of fourteen titles had been printed; the Juvenile Library (April to October 1830), which lost £900; a Library of Modern Travels and Discoveries, which never got into print; and the Standard Novels, an enormously successful series of monthly one-volume reprints at 6s. each which began in February 1831 and concluded in 1854 with volume 126. The first inexpensive reprints of Jane Austen's fiction appeared in 1833 as numbers 23, 24, 28, and 30 of the Standard Novels. Many other novels in this series were written by American authors, and most incorporated authorial changes or additions that allowed Colburn and Bentley to claim that these editions reproduced ‘the texts finally approved by their authors’. Between 1829 and 1832 Colburn and Bentley had 107,070 books printed, exclusive of the Standard Novels, and had 31,845 of these remaindered or wasted (pulped). Among their best-sellers were Bulwer's Paul Clifford and Eugene Aram, Disraeli's The Young Duke, and four silver-fork novels by the prolific Catherine Gore. The firm also spent £27,000 ‘puffing’ their own publications in advertisements and in periodicals they owned.

In autumn 1831 Morgan concluded that Colburn's debts exceeded £18,000, and that a Mr Willis, one of the firm's employees, had appropriated more than £700 of the cash which retailers had remitted. Colburn sold or mortgaged his shares in several periodicals to keep the firm solvent, and from May until August 1832 Bentley, no longer on speaking terms with his partner, negotiated through Morgan what he characterized as ‘a kind of patchwork’ settlement (Morgan). On 1 September 1832 Bentley purchased Colburn's share for £1500, bought stock and copyrights for a further £5500, and bonded Colburn not to publish any new books within 20 miles of London. Colburn immediately violated the spirit if not the letter of the agreement; eventually Bentley received a substantial further sum to release Colburn from exile. Thereupon Colburn moved to 13 Great Marlborough Street, where he continued in business, imitating Bentley's Standard Novels and sometimes publishing Bentley's authors. Bentley meanwhile hired several of Colburn's former staff, including Morgan, who served him faithfully until he retired on 31 March 1858; also G. Dubourg, William Shoberl, Charles Ollier, Eliza Ketteridge, and John Pickersgill, brother of the portraitist Henry William Pickersgill RA (1782–1875). Within a few years, having made successful hits with Edward Bulwer's Last Days of Pompeii and William Harrison Ainsworth's Rookwood, Bentley proposed to buy the Monthly Magazine in order to compete with Colburn's successful New Monthly Magazine.

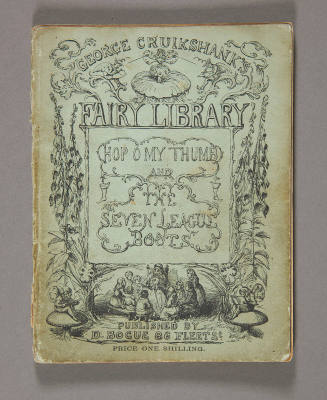

Over a weekend late in October 1836, Morgan, who disliked the Monthly (an ‘old harridan ... little better than a Fleet St. walker’), came up with a proposal for a new 2s. 6d. periodical ‘devoted to humorous papers by popular writers’. Bentley, ‘almost frantic with approbation’, at first adopted Morgan's suggestion for a title, The Wits' Miscellany. But after hearing objections from Dickens and his friends, the publisher switched to Bentley's Miscellany, prompting Barham's quip, ‘Why go to the other extreme?’ and Theodore Hook's observation that the title was ominous: ‘Miss-sell-any’ (Patten, Cruikshank, 2.51). On 4 November 1836 Bentley signed an agreement to hire Charles Dickens to edit the periodical at £20 monthly and for a further 20 guineas ‘to furnish an original article of his own writing, every monthly Number, to consist of about a sheet of 16 pages’ (Letters of Charles Dickens, 1.649–50). At the same time Bentley paid George Cruikshank £50 for the use of his name as illustrator, contracted to pay 12 guineas for a monthly etching, and subjected the artist to a £100 penalty should he draw anything for Colburn. The first numbers of the new magazine, which from February contained the instalments of Oliver Twist as Dickens's ‘original article ... monthly’, proved very popular, even though conservatives such as Barham disliked the novel's ‘Radicalish tone’ (Life and Letters, 2.24); sales rose and Dickens even received bonuses. But by autumn Dickens and Bentley were fighting over editorial prerogatives. Dickens threatened to resign on several occasions—Morgan thought that Dickens's ‘feelings of discontent’ could be attributed to ‘the meddling agency’ of John Forster (Morgan). But Cruikshank and Barham as intermediaries managed to reconcile the co-editors, and Bentley acceded to a total of nine agreements restating, in Dickens's favour, the terms upon which Bentley would purchase Boz's editorial services and Dickens's next two novels. The final break with the ‘Burlington Street Brigand’ (Letters of Charles Dickens, 1.619) came in February 1839, and at that point Ainsworth took over as the magazine's editor. Within a few years Ainsworth and Cruikshank too had severed relations with Bentley because of editorial and financial disputes, partly stemming from the very success of their enterprises, which were governed by contracts that did not allow sufficiently for additional remuneration and enhanced editorial control.

During the 1830s and 1840s Bentley was at the top of his form. A ‘serious-minded craftsman-booklover’ (Sadleir), Bentley offered good value and well-produced books. As his business prospered (in 1839 Bentley had amassed a nest-egg of about £6000), he enjoyed hosting Miscellany dinners at the Red Room at New Burlington Street, where ‘all the very haut ton of the literature of the day’ gathered, Thomas Moore recorded in his Journal (5.2023, 21 Nov 1838). Bentley was publishing leading British authors: Henry Luttrell, Moore, Isaac Disraeli and his son Benjamin, Theodore Hook, Frances Trollope, and Caroline Norton. He also had virtually a monopoly on American authors: the Standard Novels eventually printed twenty-one by James Fenimore Cooper. And with taste and discernment Bentley picked outstanding continental writers: Alphonse de Lamartine, the vicomte de Chateaubriand, Louis-Adolphe Thiers, François Guizot, Leopold von Ranke, and Theodor Mommsen.

But Bentley was also slow and often imitative of other publishers, and he had a strong bourgeois streak that prompted him to stand upon his proprietorial and editorial dignity, even when he lost contributors through his stubbornness. Moreover, he repeatedly overreached: symbolically, in obtaining in 1833 an appointment as ‘publisher in ordinary to his majesty’ (the firm never published anything for William IV or Victoria over sixty-five years); practically, especially in the 1840s and 1850s, when he tried to launch major periodicals. A 6d. weekly newspaper, Young England, which began on 4 January 1845, enjoyed the assistance of the Hon. George Smythe (the original of Coningsby) and Lord John Manners, to no avail; it failed after fourteen issues. A decade later, Bentley's Quarterly Review, a 6s. quarterly appearing one month before the venerable Quarterly Review to try to steal its market, started bravely on 28 February 1859 with John Douglas Cook, later successful as editor of the Saturday Review, as editor and Lord Robert Cecil as political editor. By 8 June, when he discontinued the venture, Bentley to his ‘extreme regret and mortification’ (Bentley to Cook, 31 May 1859, Gettmann, 146) had lost £640.

In the later 1840s Bentley became increasingly rash, ‘more self willed and impulsive’, says Morgan. Barham retired in 1843; lacking any steadying hand, Bentley found himself adrift in a cut-throat market with inadequate resources and many losing properties. The circulation of Bentley's Miscellany dropped by two-thirds; Mrs Gore thought the magazine nothing but ‘hashed mutton’: ‘your procession of authors’, she told Bentley on 2 May 1847, ‘wants an elephant at its head’ (Gettmann, 143–4). Competition from Routledge and Colburn forced Bentley to reduce the price of his Standard Novels to unprofitable levels. To stay solvent, he sold the Miscellany to Ainsworth for £1700 in October 1854 with the proviso that the transfer of ownership could ‘scarcely be known to the outer world’ (ibid., 24); he off-loaded 17,730 volumes to a Belfast remainder dealer for £525; and, his mind ‘clouded over with adversity’ according to Morgan, he beseeched his commercial authors to buy back their copyrights. The firm's debts to family members, authors, and suppliers were so great that its stock, copyrights, stereo plates, steel etchings, and bound volumes were sold in three auctions: 26–7 February 1856; 14 July 1856; and 18–22 July 1857. Nevertheless, Bentley's affairs remained in such bad shape that the printers William Clowes and G. A. Spottiswoode were appointed inspectors of the firm. Although their supervision nominally ended on 31 March 1858, some debts ran for decades beyond that date. Bentley suffered a further, grievous blow in 1857: he lost about £16,000 as a consequence of the Lords' decision to void British copyright in American authors.

The 1860s ushered in an upswing in Bentley's fortunes. Geraldine Jewsbury, who became a ‘decisive’ and enterprising publisher's reader for the firm at this time (R. Bentley, ‘Diary’, 3 March 1859), recommended Mrs Henry Wood's racy novel East Lynne; it went through four editions in six months in 1861. Bentley was still then so strapped for funds he had to publish on half-profits, however, so he reaped no huge gains. While in his dyspeptic moments Bentley believed that grasping writers were convinced that ‘Publishers drink their claret out of authors' brains’ (ibid., 24 Sept 1859), and that some of his printing industry colleagues conspired against him, he was still held in high repute by the Stationers' Company, which elected him upper warden on 6 July 1861. On 27 January 1866 Bentley purchased Temple Bar from George Augustus Sala for £2750; Edmund Yates edited it for two years, then George Bentley took over, merging it with Bentley's Miscellany, repurchased from Ainsworth for a mere £250. From the start, Temple Bar was a money-maker; but on the other side of the ledger, Bentley gained prestige while losing considerable money issuing Peter Cunningham's complete edition of Horace Walpole's Letters.

In 1867 a severe accident at Chepstow railway station left Bentley shaken and enfeebled. He relinquished management to his son and spent the next four years in fragile health, during which time he knitted up the ravelled ends of old friendships and revisited former triumphs. A reissue of Barham's Ingoldsby Legends with a specially commissioned frontispiece by George Cruikshank, to whom he was now reconciled, heartened the old man. On 10 September 1871 Bentley died at Ramsgate.

Bentley was remembered variously by his contemporaries. The Bookseller on 3 October 1871 eulogized his ‘fine taste’ and ‘integrity’ but added that ‘his judgment was at times warped by his predilections, and he frequently over-estimated the value of works offered him’. The American historian W. H. Prescott, who broke with Bentley in the 1850s, noted his ‘tricky spirit’ (Gettmann, 107), and Dalton Barham wrote to his daughter Caroline that Bentley was determined ‘to judge for himself in all matters of literary taste’ (Life and Letters, 2.108–9, 20 Oct 1840). Una Pope-Hennessy's oft-quoted assessment of Bentley's character, ‘purblind and mean of soul’, is certainly overwrought (Pope-Hennessy, 83). Because Bentley's quarrels with Dickens have been so frequently retold from Dickens's standpoint, Bentley's reputation has suffered, even though in those protracted contretemps Bentley had, as Dickens's biographer Edgar Johnson concedes, ‘the law on his side at every stage of their contention’ (Johnson, 1.252). Bentley's major contributions to nineteenth-century publishing are the Standard Novels—freshly revised texts of major contemporary authors made affordable for the middle class; Bentley's Miscellany and Temple Bar; the quality of his author list and of his book manufacture; his introduction of high-calibre international writers to British readers; and his founding of a family publishing firm that lasted through two further generations.

Robert L. Patten

Sources R. A. Gettmann, A Victorian publisher: a study of the Bentley papers (1960) · R. L. Patten, Charles Dickens and his publishers (1978) · E. S. Morgan, ‘A brief retrospect’, 4 July 1873, University of Illinois, Bentley MSS · R. Bentley sen., ‘Recollections of Edward Bentley [and early life]’, The archives of Richard Bentley & Son, 1829–1898 (1976) [microfilm] · R. Bentley, ‘Diary’, The archives of Richard Bentley & Son, 1829–1898 (1976) [microfilm] · M. Sadleir, XIX century fiction: a bibliographical record based on his own collection, 2 vols. (New York, 1969) · R. L. Patten, George Cruikshank's life, times, and art, 2 vols. (1992–6) · R. P. Wallins, ‘Richard Bentley’, British literary publishing houses, 1820–1880, ed. P. J. Anderson and J. Rose, DLitB, 106 (1991), 39–52 · The letters of Charles Dickens, ed. M. House, G. Storey, and others, 1 (1965) · J. Forster, The life of Charles Dickens, 3 vols. (1872–4) · E. Johnson, Charles Dickens: his tragedy and triumph, 2 vols. (1952) · G. Bentley, letter, The Times (8 Dec 1871) · GM, 5th ser., 1 (1868) · The Bookseller (3 Oct 1871) · The Bookseller (7 Sept 1898) · The life and letters of ... Richard Harris Barham, ed. R. H. D. Barham, 2 vols. (1870) · W. G. Lane, Richard Harris Barham (1967) · T. Moore, Journal, ed. W. S. Dowden, 5 (1988) · A. Ingram, Index to the archives of Richard Bentley & Son, 1829–1898 (1977) · M. Turner, Index and guide to the lists of the publications of Richard Bentley & Son, 1829–1898 (1975) · M. Plant, The English book trade (1939) · U. Pope-Hennessy, Charles Dickens (1946) · ‘Bentley, George’, DNB · ‘Bentley, Samuel’, DNB · ‘Nichols, John’, DNB · ‘Pickersgill, Henry William’, DNB · ‘Smythe, George Augustus Frederick Percy Sydney’, DNB · K. Chittick, Dickens and the 1830s (1990)

Archives BL, corresp., accounts, and papers, Add. MSS 46560–46682, 59622–59651 · Bodl. Oxf., corresp., diaries, and papers · Boston PL, corresp. · Hunt. L., letters · NL Scot., corresp. · U. Cal., Los Angeles · University of Illinois, Chicago :: Bodl. Oxf., letters to Benjamin Disraeli · Essex RO, Chelmsford, corresp. with G. D. Warburton · Harvard U., Houghton L., corresp. with W. H. Prescott · NL Wales, corresp. with Lady Llanover

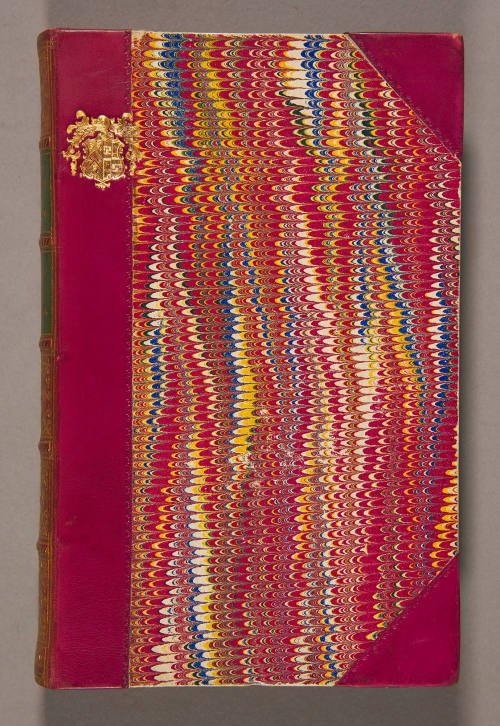

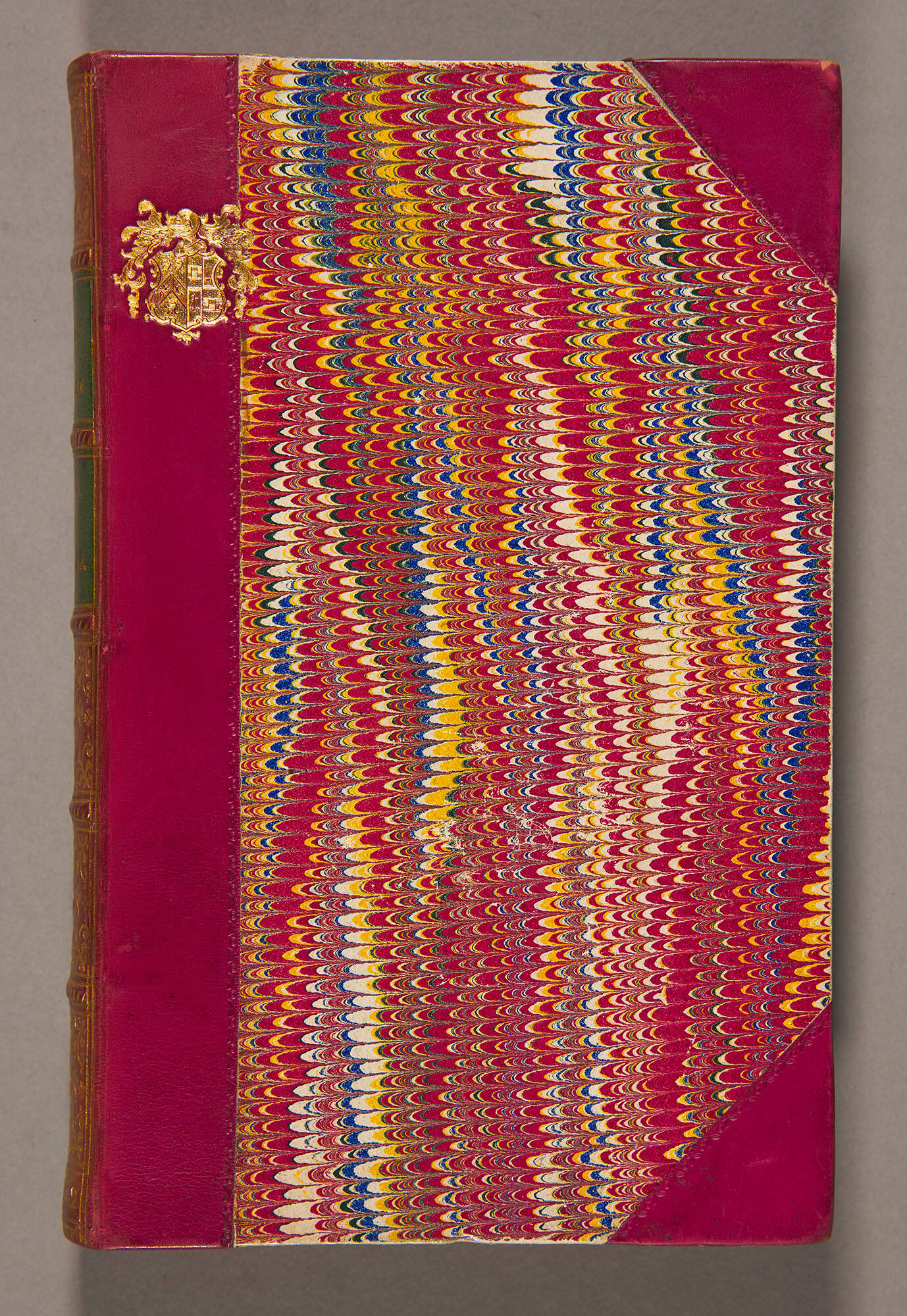

Likenesses C. Baugniet, lithograph, 1844, NPG [see illus.] · J. Heath, line engraving (after J. G. Eccardt), BM, NPG; repro. in The works of Horatio Walpole, earl of Oxford, ed. R. Walpole and M. Berry, 5 vols. (1798) · photograph (after oil painting), repro. in Gettmann, Victorian publisher

Wealth at death under £9000: probate, 20 Oct 1871, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–15

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Robert L. Patten, ‘Bentley, Richard (1794–1871)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/2171, accessed 6 Oct 2015]

Person TypeInstitution

Last Updated8/7/24

Terms

Canterbury, 1815 - 1886, London

Sussex, 1799 - 1870, Boulogne

Portsmouth, England, 1828 - 1909, Box Hill, England

Black Bourton, England, 1768 - 1849, Edgeworthstown, Ireland