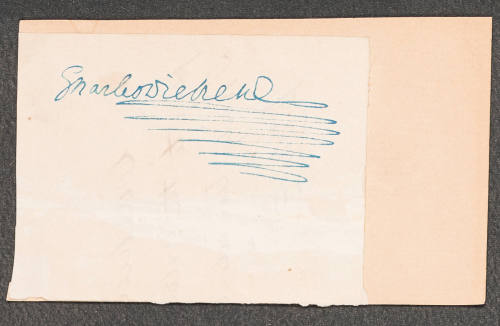

Charles Dickens

Portsmouth, 1812 - 1870, London

LC name authority rec. n78087607

LC Heading: Dickens, Charles, 1812-1870

Biography:

Dickens, Charles John Huffam (1812–1870), novelist, was born on 7 February 1812 at 13 Mile End Terrace, Portsea, Portsmouth (since 1903 the Dickens Birthplace Museum), the second child and first son of John Dickens (1785–1851), an assistant clerk in the navy pay office, stationed since 1808 in Portsmouth as an ‘outport’ worker, and his wife, Elizabeth, née Barrow (1789–1863).

Parents and siblings

Dickens's father, John, was the younger son of William Dickens (d. 1785) and Elizabeth Ball (d. 1824), respectively butler and housekeeper in the Crewe family, who had married in 1781. Old Mrs Dickens was fondly remembered by the Crewe children as ‘an inimitable story-teller’ (Allen, 12). On 13 June 1809 John married Elizabeth Barrow; her father, Charles Barrow, was a senior official in the navy pay office who shortly afterwards had to flee the country, having been detected embezzling public money. John's genial and convivial personality, his air of gentility, his financial improvidence, and his fondness for grandiloquent phrases are all mirrored in Mr Micawber in David Copperfield. Certain of these traits reappear in the character of Mr Dorrit (Little Dorrit) where, however, they are presented much less sympathetically. Elizabeth seems to have had, like her husband, a lively and irrepressibly optimistic temperament and aspects of her personality have traditionally been identified in both Mrs Nickleby (Nicholas Nickleby) and Mrs Micawber.

The couple's first child, the musically talented Frances Dickens, always known as Fanny, was born in 1810 and was a much loved companion during Dickens's earliest years. In 1837 she married the singer Henry Burnett (1811–1893) and remained very dear to Dickens until her untimely death from consumption in 1848; he commemorated their childhood companionship in his journal Household Words (6 April 1850) with a piece entitled ‘A Child's Dream of a Star’ (Reprinted Pieces, 1858). John's and Elizabeth's other children, born after Charles, were: Alfred Allen, who died in infancy in 1814; Letitia Mary (1816–1893), who married the architect, civil engineer, and active sanitary reformer Henry Austin; Harriet, born in 1819, who died in childhood; Frederick William, always known as Fred (1820–1868); Alfred Lamert (1822–1860); and Augustus Newnham (1827–1866). Alfred Lamert was the only one of Dickens's brothers to make a satisfactory career for himself (as a civil engineer); in adult life the marital problems and generally feckless behaviour of both Fred and Augustus created annoyances for Dickens (as did the continued financial irresponsibility of his father) but he seems always to have retained some brotherly affection for them—even for Augustus, who in 1857 deserted his blind wife and emigrated with another woman to Chicago, living openly with her there as ‘Mr and Mrs Dickens’.

Childhood and education

After a two-year spell back in London working in Somerset House (1815–16), John Dickens was posted first, briefly, to Sheerness and then to Chatham, where he settled with his growing family at 2 Ordnance Terrace, a six-roomed house, advertised as ‘commanding beautiful views ... and fit for the residence of a genteel family’ (Allen, 40). His income was rising but so were expenses. Two live-in servants were employed, one of whom, the teenage nursemaid Mary Weller, later gave Robert Langton her reminiscences of Dickens as a child. Dickens recalled his mother teaching him, ‘thoroughly well’, the alphabet and the rudiments of English and, later, Latin (Forster, 4). He and Fanny attended a nearby dame-school and later (1821?–1822?) he became a promising pupil at a ‘classical, mathematical, and commercial school’ run by the Revd William Giles, the son of a Baptist minister. By now the family had moved into a slightly smaller house, 18 St Mary's Place, perhaps as a result of John Dickens's increasing financial difficulties. These Chatham years were hugely important for the development of Dickens's imagination. His vivid, astonishingly detailed, memories of everything he experienced there, and of his voracious childhood reading (he was, Mary Weller recalled, ‘a terrible boy to read’; Langton, 25), richly fed his later fiction and inspired some of his finest journalistic essays. Being ‘a very little and a very sickly boy ... subject to attacks of violent spasm’ (Forster, 3), he was debarred from sporting activities, though he enjoyed games of make-believe with his friends and getting up magic-lantern shows, also performing (sometimes as duets with Fanny) comic songs and recitations with, according to Mary Weller, ‘such action and such attitudes’ (Langton, 26). John Dickens was proud of his children's singing talents which were sometimes publicly exhibited at the Mitre tavern in Rochester. This old city, which adjoins Chatham, with its ruined castle, ancient cathedral, and picturesque High Street, fascinated the young Dickens and was indeed ‘the birthplace of his fancy’ (Forster, 8). He loved dreamily watching the River Medway with ‘the great ships standing out to sea or coming home richly laden’ and all the other varied shipping described in the 1863 essay ‘Chatham Dockyard’ (The Uncommercial Traveller). Also, it was the little Rochester playhouse that gave him his earliest thrilling experiences of what became one of the master passions of his life, the theatre, as recalled, along with other aspects of the city, in another Uncommercial Traveller essay, ‘Dullborough Town’:

Richard the Third, in a very uncomfortable cloak, had first appeared to me there, and had made my heart leap with terror by backing up against the stage-box in which I was posted, while struggling for life against the virtuous Richmond.

He constantly read and reread the books in his father's little library—the eighteenth-century essayists, Robinson Crusoe, The Vicar of Wakefield, Don Quixote, the works of Fielding and Smollett, and other novels and stories (most notably The Arabian Nights and The Tales of the Genii). These books made up that ‘glorious host’ that, as he wrote in the character of the young David when incorporating this real life material into chapter 4 of David Copperfield, ‘kept alive my fancy’ when life turned suddenly very bleak. Indeed, these books became fundamental to his imaginative world, as is clearly attested by the innumerable quotations from, and allusions to, them in all his writings.

In 1822 John Dickens was recalled to London and the family squeezed itself into a smaller house at 16 Bayham Street in the very lower-middle-class suburb of Camden Town. This was a great shock to the young Dickens, who now began hearing much about his father's increasing financial problems. The abrupt termination of his schooling distressed him greatly. Money was found to send Fanny to the Royal Academy of Music but Dickens was left, as he once told his friend and biographer John Forster, to brood bitterly on ‘all [he] had lost in losing Chatham’ and to yearn ‘to [be] taught something anywhere!’ (Forster, 9). But he began also to be fascinated by the great world of London, transferring to it ‘all the dreaminess and all the romance with which he had invested Chatham’ and deriving intense pleasure from being taken for walks in the city, especially anywhere near the slum area of Seven Dials which invariably inspired him with ‘wild visions of prodigies of wickedness, want and beggary!’ (ibid., 11). Forster characterizes the boy's response to Seven Dials as ‘a profound attraction of repulsion’ (ibid.), a phrase that goes very much to the heart of the later Dickens's attitude towards grim, squalid, or horrific subjects. John's financial situation continuing to deteriorate, and a rather desperate attempt of Elizabeth's to establish a school for young ladies having failed utterly, he was committed to the Marshalsea debtors' prison on 20 February 1824 and was soon joined there by Elizabeth and the younger children. Employment had been found for Dickens by a family friend at Warren's blacking factory at Hungerford Stairs just off the Strand. There he pasted labels on blacking bottles for 6s. a week, lodging first in Little College Street with a Mrs Roylance (on whom he modelled Mrs Pipchin in Dombey and Son) and later in Lant Street, Borough, closer to the prison. The deep personal and social outrage, and sense of parental betrayal, that Dickens experienced at the time was a profound grief that he never entirely outgrew, and an intense pity (also intense admiration) for his younger self was to be a mainspring of his fiction from Oliver Twist to Little Dorrit. In the fragmentary autobiography he wrote in the 1840s, and which Forster incorporated into his biography, he wrote:

No words can express the secret agony of my soul as I sunk into this companionship [of ‘common men and boys’] ... and felt my early hopes of growing up to be a learned and distinguished man, crushed in my breast. The deep remembrance of the sense I had of being utterly neglected and hopeless; of the shame I felt in my position; of the misery it was to my young heart to believe that, day by day, what I had learned, and thought, and delighted in, and raised my fancy and my emulation up by, was passing away from me, never to be brought back any more; cannot be written. (Forster, 26)

John Dickens left the prison on 28 May, having been through the insolvency court, and having also received a legacy from his mother, but his son seems to have remained working at the blacking factory for another nine or ten months (Allen, 103). He was finally taken away when John for some reason quarrelled with the proprietor. Elizabeth tried to arrange for the boy's return, for which Dickens never forgave her. John, however, had retired from the pay office on health grounds and was now receiving an Admiralty pension, and said that his son should go back to school. Dickens then became a day boy at the grandly named Wellington House Classical and Commercial Academy in the Hampstead Road, later depicting it and William Jones, its brutal and ignorant proprietor, in David Copperfield (‘Salem House’) and ‘Our School’ (Reprinted Pieces, 1858). From the day that he entered Jones's school until the day he died he told no one, his wife and his friend Forster alone excepted, about his time in the blacking factory, or about his father's imprisonment. His parents seem likewise to have maintained a total silence on the subject. The first that anyone, the general public or even his own children, knew about these things was when Forster published passages from his unfinished autobiography in the first volume of his Life of Charles Dickens (1876). In March 1827 the Dickens family's finances were again in crisis and Dickens's schooling once more ended suddenly. At fifteen he began work as a solicitor's clerk, a humdrum occupation that he found unappealing, though his experiences at both the firms for which he worked (Charles Molloy of Symond's Inn, and Ellis and Blackmore of Raymond Buildings) provided good material for many passages of legal satire in his later sketches and fiction. During his leisure hours he greatly extended and deepened his knowledge of London, London street life, and London popular entertainments. A fellow clerk, George Lear, later recalled, ‘I thought I knew something of the town but after a little talk with Dickens I found I knew nothing. He knew it all from Bow to Brentford’ (Kitton, 131).

The young journalist, 1828–1836

By 1828 John Dickens, launched on a new career as a journalist, had established himself as a reporter on his brother-in-law's newly launched paper the Mirror of Parliament. Dickens evidently also decided to try for a career in journalism as being—potentially, at least—a good deal more rewarding than drudging on at Ellis and Blackmore's on 15s. a week (exactly Bob Cratchit's wages in A Christmas Carol). By fierce application, entertainingly recalled in David Copperfield, he taught himself Gurney's system of shorthand, and in November 1828 left the lawyers' office to share a box for freelance reporters in Doctors' Commons rented by Thomas Charlton, a distant family connection. It was probably some time during 1829 that he first met a diminutive beauty called Maria Beadnell (1810–1886) and fell headlong in love with her. This passion was to dominate his emotional life for the next four years, causing him much torment, not so much because of the objections that Maria's prosperous banker father no doubt had about entertaining a struggling young freelance reporter as a prospective son-in-law, but because Maria herself seems to have been of a flirtatious disposition, so that Dickens could never be sure of her real feelings towards him. His steely ambition to make a mark in the world in one way or another was given a keener edge by his passionate desire to make her his wife. He sought to improve himself by reading in the British Museum (Shakespeare and the classics, English and Roman history), having applied for a reader's ticket at the first possible moment, just after his eighteenth birthday. Aware that he had a definite histrionic talent, he also considered the idea of a stage career and obtained (spring 1832) an audition at Covent Garden, but in the event a bad cold prevented him from attending and shortly afterwards came an opportunity to develop his journalistic career. During 1830 or 1831 he had begun to get work, perhaps as a supernumerary, on his uncle's paper and then in 1832 he was taken on to the regular staff of a new evening paper, the True Sun. He rapidly acquired a reputation as an outstanding parliamentary reporter and, having inherited to the full his father's love of convivial occasions, pursued at the same time an energetic social life. In April 1833, anticipating a favourite activity of his later years, he organized some elaborate private theatricals at his parents' home in Bentinck Street. Shortly afterwards came the final cruel collapse of all hopes of winning Maria's heart. The intense pain this caused him left a permanent scar on his emotional life, although he was able to present Maria and his ardent youthful love for her in a comic-sentimental light in the Dora episodes of David Copperfield. Many years later he wrote to her that ‘the wasted tenderness of those hard years’ had bred in him ‘a habit of suppression ... which I know is no part of my original nature, but which makes me chary of showing my affections, even to my children, except when they are very young’ (Letters, 7.543).

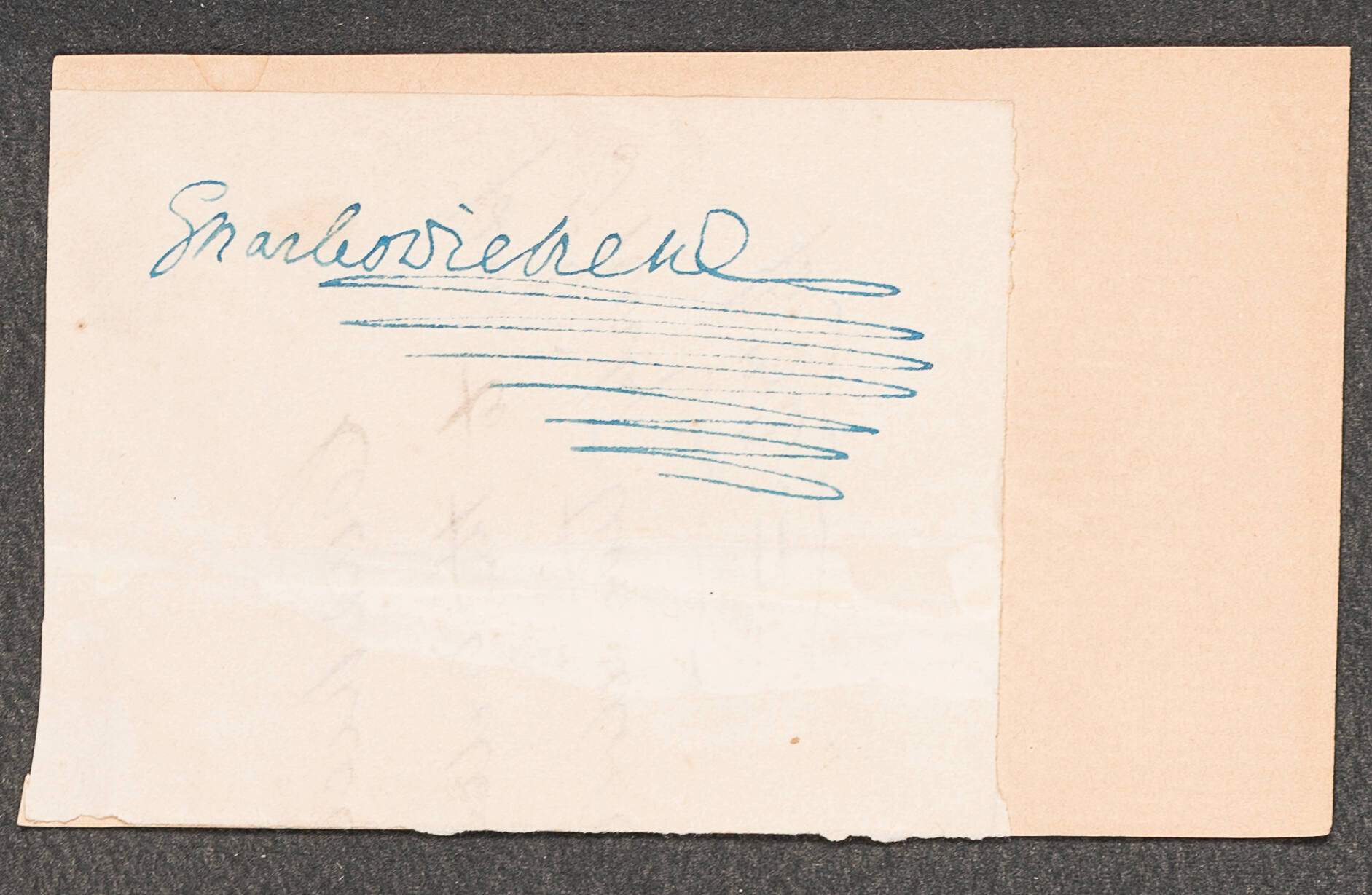

In December 1833 Dickens's first published literary work appeared in the Monthly Magazine; it was a farcical little story of middle-class manners called ‘A Dinner at Poplar Walk’ (later retitled as ‘Mr Minns and his Cousin’). Over the next year it was followed, in the same periodical (the owner of which, a Captain Holland, could not offer any payment) by several other stories in a similar vein, for the sixth of which Dickens first used the pen-name Boz (derived from his little brother Augustus's mispronunciation of Moses, his Goldsmithian family nickname). Dickens's appointment, in August 1834, to the reporting staff of the leading whig newspaper, the Morning Chronicle, at a salary of 5 guineas per week, placed his career on a firm footing and he was soon distinguishing himself not only as a brilliant shorthand writer but also as a most effective and efficient special correspondent, reporting provincial elections and other events, and being exhilarated by the keen competition provided by the Times correspondent. In September he began to contribute a series of ‘Street Sketches’, illustrative of everyday London life, to the Chronicle. These attracted favourable notice and his offer to write, for extra pay, a similar series, twenty ‘Sketches of London’, for the newly founded sister paper the Evening Chronicle, was welcomed by that paper's editor, George Hogarth. The first, ‘Hackney Coach Stands’, appeared in January 1835 and the last, ‘Our Parish (the Ladies' Societies)’, in August 1835. Dickens then began yet another series, twelve ‘Scenes and Characters’, in Bell's Life in London. The last of these, ‘The Streets at Night’, appeared in January 1836, to be swiftly followed by a collected two-volume edition, Sketches by Boz, published by John Macrone and illustrated by the renowned comic artist George Cruikshank. Dickens probably owed his introduction to Macrone and Cruikshank to William Harrison Ainsworth who had become a close friend, providing Dickens with his first entrée into literary circles. The two-volume edition of Sketches by Boz, for which Dickens specially wrote two non-comic pieces, ‘A Visit to Newgate’ and ‘The Black Veil’, was extremely well received. The sketches were praised for their humour, wit, touches of pathos, and the ‘startling fidelity’ of their descriptions of London life (Collins, Critical Heritage, 30). Meanwhile, he continued with all his routine journalistic work and coped as best he could with his father's recurring financial crises, helped by close friends like his fellow journalist Thomas Beard, who was to remain a lifelong and much loved friend, and the young lawyer Thomas Mitton, who acted as his solicitor for many years. He took lodgings for himself and his fourteen-year-old brother Fred in Furnival's Inn, Holborn. By this time he had become acquainted with George Hogarth's family and had become attracted to the eldest daughter, Catherine (1816–1879), though without the passionate intensity that had characterized his love for Maria Beadnell, and he became engaged to her during the summer of 1835. Catherine was small and pretty like Maria, with blue eyes and brown hair—also gentle, amiable, and proficient in many of the so-called ‘accomplishments’ expected of young ladies at this time.

Pickwick, marriage, and the coming of fame, 1836

In February 1836, just after the appearance of the two-volume Sketches by Boz, two young booksellers who were moving into publishing, Edward Chapman and William Hall, approached Dickens to write the letterpress for a series of steel-engraved plates by the popular comic artist Robert Seymour depicting the misadventures of a group of cockney sportsmen, to be published in twenty monthly numbers, each containing four plates. They offered Dickens £14 a month for the work, an ‘emolument’ that was, as he wrote to Catherine, ‘too tempting to resist’ (Letters, 1.129). He accepted the commission despite Ainsworth's warning that he would demean himself by participating in such a ‘low’ form of publication, but stipulated that he should be allowed to widen the scope of the proposed subject ‘with a freer range of English scenes and people’. He then, he later recalled, ‘thought of Mr Pickwick, and wrote the first number’ (‘Preface’ to the Cheap Edition of Pickwick, 1847). This appeared on 31 March 1836 and on 2 April Dickens and Catherine were married at St Luke's, Chelsea. They spent their honeymoon in the Kentish village of Chalk and then set up home in the new and more spacious chambers Dickens had taken in Furnival's Inn where he was already established. On 20 April Seymour committed suicide but the publishers boldly decided to continue the series, despite disappointing initial sales. Seymour was replaced, after the brief trial of R. W. Buss, with a young artist, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), who was Dickens's main illustrator for the next twenty-three years. In recognition of the fact that Dickens was now very much the senior partner in the enterprise, the number of plates was halved, the letterpress increased from twenty-eight to thirty-two pages, and his monthly remuneration rose to £21. With the introduction of Sam Weller in the fourth number sales began to increase dramatically and soon Pickwick was the greatest publishing sensation since Byron had woken to find himself famous, as a result of the publication of the first two cantos of Childe Harold, in 1812. By the end of its run in November 1837 Dickens's monthly serial had a phenomenal circulation of nearly 40,000 and had earned the publishers £14,000, an appreciable amount of which would have stemmed from the fees paid by advertisers who supplied inserts or took space in the ‘Pickwick Advertiser’ that eventually occupied twenty-four extra pages each month. The depiction of the benevolent old innocent Mr Pickwick and the streetwise but good-hearted Sam Weller as a sort of latter-day Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, the rich evocation of that pre-railway, pre-Reform Bill England that was so rapidly disappearing, the idyll of Dingley Dell, the sparkling social comedy and hilarious legal satire, the comic and pathetic scenes in the Fleet prison, the astonishing variety of vividly evoked and utterly distinct characters, the bravura wit and, above all, that ‘endless fertility in laughter-causing detail’ that Walter Bagehot later called ‘Mr Dickens's most astonishing peculiarity’ (Collins, Critical Heritage, 395)—all these things combined to give The Pickwick Papers a phenomenal popularity that transcended barriers of class, age, and education. Mary Russell Mitford wrote to an Irish friend, ‘All the boys and girls talk [Dickens's] fun—the boys in the street; and yet those who are of the higher taste like it the most. ... Lord Denman studies Pickwick on the bench while the jury are deliberating’ (ibid., 36).

Dickens could hardly have anticipated success on this scale or he would probably not have committed himself to so many other projects such as turning one of his sketches into a two-act ‘burletta’, The Strange Gentleman, as a vehicle for the comedian John Pritt Harley. It was successfully produced at the St James's Theatre (9 September 1836) and ran for fifty nights. He also wrote, under the pseudonym Timothy Sparks, an anti-sabbatarian pamphlet, Sunday under Three Heads, the precursor of many later attacks on what he saw as blatantly hypocritical and class-biased legislative proposals. By late October he had clearly decided that he would be able to live by his pen and resigned from his Morning Chronicle post. Dickens was, in fact, grotesquely over-committed to publishers who were all eager to sign up the dazzling new literary star. He accepted Richard Bentley's invitation to edit a new monthly magazine, Bentley's Miscellany, to begin publication in the new year, being already committed to write two three-volume novels for Bentley, as well as a third novel, Gabriel Vardon, the Locksmith of London, for Macrone, and another (as yet unnamed) work of the same length and nature as Pickwick for Chapman and Hall. He had been at work, with J. P. Hullah, on a rather vapid operetta, The Village Coquettes, which was produced at the St James's on 6 December but had only a short run, and throughout 1836 he had been publishing more sketches in the Morning Chronicle and elsewhere, including some of his finest work in this genre, such as ‘Meditations in Monmouth Street’. These sketches, together with earlier ones still uncollected, were gathered up in the one-volume Sketches by Boz: Second Series published by Macrone on 17 December. This volume ended with an item written specially for it, a Grand Guignol piece called ‘The Drunkard's Death’. About this time Dickens first met (probably through Ainsworth) John Forster, a young theatre critic, literary reviewer, and historian, who had moved to London from Newcastle and was already very much in the swim of the metropolitan literary world. Forster became one of Dickens's most intimate friends and his lifelong trusted literary adviser—even to some extent collaborator, since from October 1837 he read everything that Dickens wrote, either in manuscript or proof—as well as his chosen biographer. Forster's legal training and expertise made him an invaluable ally in Dickens's many disputes with publishers, the first of which was with Macrone to whom Dickens had sold the copyright of Sketches by Boz as part of a deal to release himself from the promise to write Gabriel Vardon. Macrone sought to profit from the success of Pickwick by proposing to issue both series of the Sketches in twenty monthly parts. Dickens strongly objected and tried through Forster's agency to dissuade Macrone. In the end, Chapman and Hall bought the copyright from Macrone for a substantial sum and themselves issued Sketches in monthly parts from November 1837 to June 1839, with additional Cruikshank plates and with pink covers to distinguish the work from Pickwick in its green monthly covers. At the conclusion of this serialization, the Sketches were published in one volume, described on the title-page as a ‘new edition, complete’.

The early novels, 1837–1841

The first number of Bentley's Miscellany, edited by ‘Boz’ and with illustrations by Cruikshank, came out in January 1837 and in February appeared the first instalment of Dickens's new story, Oliver Twist, or, The Parish Boy's Progress, which ran in the journal for twenty-four months (during the first ten of which Dickens was also still writing a monthly Pickwick). Oliver Twist was originally conceived as a satire on the new poor law of 1834 which herded the destitute and the helpless into harshly run union workhouses, and which was perceived by Dickens as a monstrously unjust and inhumane piece of legislation (he was still fiercely attacking it in Our Mutual Friend in 1865). Once the scene shifted to London, however, Oliver Twist developed into a unique and compelling blend of a ‘realistic’ tale about thieves and prostitutes and a melodrama with strong metaphysical overtones. The pathos of little Oliver (the first of many such child figures in Dickens), the farcical comedy of the Bumbles, the sinister fascination of Fagin, the horror of Nancy's murder, and the powerful evocation of London's dark and labyrinthine criminal underworld, all helped to drive Dickens's popularity to new heights. But there was mounting tension between himself and Bentley because of the latter's constant interference with Dickens's editorial freedom and his quibbles over the extent of Dickens's own contributions. Bentley also irritated Dickens by pressing for the delivery of a new novel (that is, the Gabriel Vardon originally contracted to Macrone, now renamed Barnaby Rudge; Dickens, having bought himself out of the arrangement with Macrone, had now signed a contract for the book with Bentley). Sometimes the relationship temporarily improved, as in November 1837, when Dickens agreed to edit for Bentley the memoirs of the great clown Joey Grimaldi (published with an ‘Introductory chapter’ and a concluding one by Dickens, and wonderful illustrations by Cruikshank, in February 1838), but at last came a complete rupture and Dickens resigned the editorship of the Miscellany in the January 1839 number. By the summer of 1840 he was fully committed to Chapman and Hall as his sole publishers, having gradually disentangled himself—with their help, and that of Forster—from all commitments to Macrone and Bentley, the latter now usually referred to by Dickens in very uncomplimentary terms (‘the Vagabond’, ‘the Burlington Street Brigand’, and so on). The promised Pickwick-style work for Chapman and Hall, now carrying the very eighteenth-century style title of The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, had begun its monthly part-issue in March 1838 and was completed in twenty numbers in October 1839. This story, which for thirteen months Dickens wrote alongside Oliver Twist, originated in his determination to expose the scandal of unwanted children consigned to remote and brutal Yorkshire schools; accompanied by Browne, he conducted an on-the-spot midwinter investigation just before beginning to write Nickleby. In this rambling, episodic, often wildly funny book, written very much in the mode of the Smollett novels Dickens had devoured as a child, the Yorkshire school setting is soon left behind, and the gallant young hero and his pathetic protégé, Smike, wander forth to undergo various adventures, both farcical and melodramatic; they are persecuted by Nicholas's wicked uncle and other villains, who also threaten the virtue of Nicholas's pure young sister Kate, but all is eventually set right by the benevolent Cheeryble brothers, though they cannot save Smike. The story is rich in unforgettable comic characters like the endlessly garrulous Mrs Nickleby and the strolling player Vincent Crummles and his troupe, and in places it resembles Sketches by Boz in its vivid evocation of particular London neighbourhoods.

Just before Dickens began Oliver Twist, he and Catherine had had their first child, Charles Culliford Boz Dickens (1837–1896), in January 1837, and had shortly afterwards moved from their Furnival's Inn chambers to a new house, 48 Doughty Street (now the Charles Dickens Museum); Dickens bought a three-year lease and paid £80 a year in rent. Staying with them was Catherine's younger sister Mary Hogarth, whose sudden death on 7 May, aged only seventeen (‘Young, beautiful and Good’ according to the epitaph Dickens composed for her headstone in Kensal Green cemetery), was a devastating blow to Dickens—so great, indeed, that he had to suspend the writing of both Pickwick and Oliver Twist for a month, a unique occurrence in his career. He had lost, he wrote, ‘the dearest friend I ever had’, one who sympathized ‘with all my thoughts and feelings more than any one I knew ever did or will’, declaring also, ‘I solemnly believe that so perfect a creature never breathed’ (Letters, 1.263, 629, 259). It was the third great emotional crisis of his life, following the blacking factory experience and the Beadnell affair, and one that profoundly influenced him as an artist as well as a man.

In all other respects Dickens's life, both professional and personal, during the later 1830s became steadily more prosperous. The sales of Nickleby ‘were satisfactory—highly so’ (Patten, 98) and Chapman and Hall were happy to fall in with his plans for editing a weekly miscellany to be called Master Humphrey's Clock, for which he would receive a weekly salary of £50 as well as a half-share of net profits. He formed close and lasting friendships with many leading figures in the world of the arts, notably the ‘eminent tragedian’ William Charles Macready (always a particularly loved and honoured friend), the painters Daniel Maclise and Clarkson Stanfield, the lawyer and dramatist Thomas Noon Talfourd, and the poet Walter Savage Landor; he was elected to both the Garrick and the Athenaeum clubs, invited to Lady Blessington's salon, and lionized generally. He also became acquainted with Thomas Carlyle, whom he greatly revered, and who profoundly influenced his thinking on social matters. He once said, ‘I would go at all times farther to see Carlyle than any man alive’ (Forster, 839). Carlyle's first impression of Dickens was that he was ‘a quiet, shrewd-looking, little fellow, who seems to guess pretty well what he is and what others are’ (Letters, 2.141). Maclise painted the twenty-eight-year-old Dickens's portrait as an elegant young writer and the portrait was engraved as the frontispiece to the volume edition of Nickleby. At the end of 1839 the growing Dickens family (Mary, always known as Mamie, was born in 1838, Kate Macready in 1839) moved into a much grander house, 1 Devonshire Terrace, Marylebone, near to Regent's Park. Dickens paid £800 for an eleven-year lease and an annual rent of £160. From 1837 onwards the family spent several weeks each summer at the little Kentish resort of Broadstairs, later described in Household Words as ‘Our Watering Place’ (‘Our English Watering Place’ in Reprinted Pieces, 1858). Here Dickens would entertain friends but would also continue working, dashing up to London from time to time for business or social occasions.

Master Humphrey's Clock began publication on 4 April 1840. Ini

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Terms

Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1817 - 1881, Boston

Kennoway, Scotland, 1798 - 1866, Belfast

Keinton Mandeville, England, 1838 - 1905, Bradford, England

Hampstead, 1811 - 1856, Boulogne

Warwick, 1775 - 1864, Florence

Chilvers Coton, Warwickshire, 1819 - 1880, London