Gilbert Abbott À Beckett

Hampstead, 1811 - 1856, Boulogne

Biography:

À Beckett, Gilbert Abbott (1811–1856), comic writer and police magistrate, was born at The Grange, Hampstead, Middlesex, on 17 February 1811, the third son of William A'Beckett (1777–1855), a reform solicitor, and his wife, Sarah Abbott. His forebears were an ancient Wiltshire family, who traced their ancestry back to the fourteenth century and claimed descent from St Thomas a Becket. He entered Westminster School on 10 January 1820, and remained there until August 1828. At this time, according to his son Arthur William À Beckett (À Beckett, 15), À Beckett quarrelled with his father and did not see him thereafter for more than two decades. On leaving school, he and his older brothers William A'Beckett (1806–1869), who went on to become chief justice in Australia, and Thomas, who also later emigrated to Australia, founded The Censor, a youthfully ebullient journal of ephemera, gossip, tales, and theatre notices. Appearing bi-weekly from 6 September 1828 to 4 April 1829, The Censor was the first of a series of short-lived periodicals of which À Beckett was proprietor and editor, including the Literary Beacon (1831), the Evangelical Penny Magazine (1832), The Thief (1833), and The Wag (1837). According to his enemy Alfred Bunn, who later attacked him as Sleekhead, À Beckett founded thirteen papers, ‘all total failures’ (Bunn, 6).

With Figaro in London, however, À Beckett developed a formula (modelled on the Paris prototype) which proved both successful and influential. Embellished by the cartoons of Robert Seymour, Figaro was dominated by gossip, humorous squibs, and above all circumstantial, opinionated, often scurrilous theatre reviews. Walter Jerrold referred to it as a journal of ‘ready fun and ... the daring of youth’ (Jerrold, Douglas Jerrold, 4), and by the time À Beckett handed the editorship over to his friend Henry Mayhew, three years after its first number had appeared on 10 December 1831, the weekly penny magazine had a circulation of 70,000 and was reputed to have brought its editor an income of more than £1000 a year. Its popularity fed directly into the far greater and longer-lasting success of Punch, for which À Beckett was the most prolific contributor from its first appearance in 1841 until the time of his death fifteen years later: Spielmann later wrote that in column inches, his copy must have neared the height of the Eiffel Tower (Altick, 44). He was also a leader writer for The Times and the Morning Herald, and as The Perambulating Philosopher he contributed regularly to the Illustrated London News.

During these years À Beckett was vigorously pursuing his interest in the theatre, not only as a reviewer but as a playwright: as house writer for the Coburg Theatre and as lessee of the Fitzroy. Some forty plays by his hand (several written in collaboration with Mark Lemon, first editor of Punch) were published, and a further twenty have been traced in the lord chamberlain's collection or in contemporary playbills. The earliest was The King Incog, performed at the Fitzroy on 9 January 1834; the last Sardanapalus, or, The ‘Fast’ King of Assyria, performed at the Adelphi on 20 July 1853. Others included The Revolt of the Work-House (Fitzroy, 24 February 1834); The Man with the Carpet Bag (Strand, 19 January 1835); The Chimes, adapted by À Beckett and Lemon from Dickens's Christmas book and performed at the Adelphi on 19 December 1844; and Timour, or, The Cream of Tartar, adapted from Monk Lewis's Timour the Tartar (Princess, 24 March 1845). À Beckett's characteristic mode was theatrical burlesque, and he is recognized as a ‘mainstay’ of that form in its heyday (Adams, 33). He also wrote Scenes from the Rejected Comedies (1844), a volume of parodies of plays by his contemporaries, including James Sheridan Knowles, Douglas Jerrold, Thomas Noon Talfourd, and Edward Bulwer-Lytton.

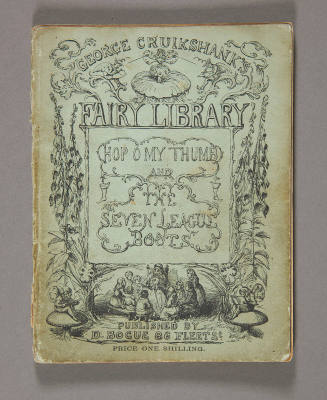

Working in collaboration with his associates on Punch, À Beckett wrote a number of volumes of burlesque prose, including The Comic Blackstone (1844), illustrated by George Cruikshank, which had originally appeared in Punch, The Comic History of England (1847), and The Comic History of Rome (1851), both illustrated by John Leech. Each of these was frequently reprinted throughout the rest of the century. He edited George Cruikshank's Table Book (1845), and along with Thackeray, Albert Smith, and the Mayhew brothers À Beckett was a contributor to The Comic Almanack (1835–53). Under the pseudonym Poz he wrote imitations of Dickens, Oliver Twiss, the Workhouse Boy (four weekly parts, 1838) and Posthumous Papers of the Wonderful Discovery Club (1838), a children's book illustrated by Leech, Hop o' my Thumb (1844), and a book of humour also illustrated by Leech, The Fiddle Faddle Fashion Book (no date).

At the same time as he was engaged in these literary and theatrical activities, À Beckett was building a legal career. He entered Gray's Inn on 25 April 1828 and was called to the bar on 27 January 1841, soon earning a reputation as an ‘excellent and upright lawyer’ (The Times, 3 Sept 1856). He worked for a time with the poor-law commission, writing well-received reports on the laws of settlement and removal and on the Andover workhouse scandal. On the strength of these reports he was appointed in 1849 as a Metropolitan Police magistrate, first for Greenwich and latterly for Southwark, where he was noted for his benevolence in distributing funds from the poor box to the deserving poor, and for his ‘acuteness, humanity and impartiality’ in rendering justice; ‘one of the best’ magistrates of his day, was the verdict of The Times in its obituary notice (ibid.).

À Beckett was a member of the Reform Club from 1841, and of the Garrick Club from 1842. On 21 January 1835 he married Mary Anne (1817–1863), daughter of Joseph Glossop, the builder of the Coburg Theatre. They had four sons, including Gilbert Arthur À Beckett (1837–1891), and two daughters. From 1845 to 1847 they lived at Portland House, Fulham, Middlesex, and from 1848 until his death in 1856 their address was 10 Hyde Park Gate South, Kensington Gore, London. Their style of living seems to have been beyond their means, because a number of surviving letters in the Punch archives are pleas to his publisher, Frederick Evans, for advances on wages due to him, and three years after his death his widow successfully petitioned the Royal Literary Fund for financial assistance, and was granted £60.

On 30 August 1856, while on holiday with his family in France, À Beckett died suddenly and unexpectedly of typhus at Boulogne, predeceased by one of his sons from the same fever. Expressions of admiration for his ‘great ability’ and grief at his death are to be found in the letters of Dickens (Letters of Charles Dickens, 4.137; 8.179–82) and of Jerrold (Jerrold, Douglas Jerrold, 2.636–42), whom À Beckett was visiting in Boulogne at the time. His remains were later removed to Highgate cemetery, where a monument was erected to his memory. Its inscription (reproduced in Illustrated London News, 13 June 1857) repeats Jerrold's praise in the Punch obituary (13 September 1856) of À Beckett as ‘a genial manly spirit; singularly gifted with the subtlest powers of wit and humour; faculties ever exercised by their possessor to the healthiest and most innocent purpose’.

Paul Schlicke

(Paul Schlicke, ‘À Beckett, Gilbert Abbott (1811–1856)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2009 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/26, accessed 16 May 2016])

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Haddington, Scotland, 1813 - 1889, London

Kennoway, Scotland, 1798 - 1866, Belfast

Portland, Maine, 1838 - 1925, Salem, Massachusetts