Ernest Francisco Fenollosa

Salem, Massachusetts, 1853 - 1908, London

LC Heading: Fenollosa, Ernest, 1853-1908

Fenollosa, Ernest Francisco, Tei-Shin, and Kano Yeitan Masanobu (Japanese names)

Date born: 1853

Place Born: Salem, MA

Date died: 1908

Place died: London, United Kingdom

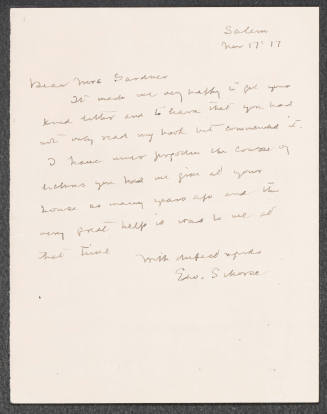

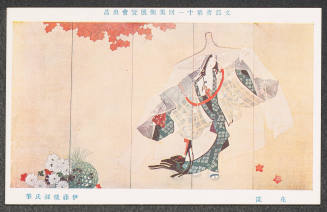

Curator of Oriental art at the Boston Museum of Fine Art, 1890-96. Fenollosa was the son of Manuel Francisco Ciriaco Fenollosa and Mary Silsbee (Fenollosa). He attended Hacker Grammar School in Salem, Massachusetts, and the Salem High School before graduating from Harvard in the class of 1874. He continued study at Cambridge University in philosophy and divinity. After a year at the art school at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, during which time he married Lizzie Goodhue Millett, he traveled to Japan in 1878 (at the invitation of American zoologist and Orientalist Edward Sylvester Morse) to teach political economy and philosophy at the Imperial University at Tokyo. He studied the indigenous ancient temples, shrines and art treasures, many of which were in a neglected state. He helped revive the Nihonga (Japanese) style of painting together with Japanese artists Kan? H?gai (1828-1888) and Hashimoto Gah? (1835-1908). After eight years at the University, he helped found the Tokyo Fine Arts Academy and the Imperial Museum acting as its director in 1888. He converted to Buddhism, and changed his name to Tei-Shin. He also adopted the name Kan? Yeitan Masanobu, suggesting that he had been admitted into the ancient Japanese art academy of the Kan?. Among Fenollosa's accomplishments were the first inventory of Japan's national treasures, and in so doing he discovered ancient Chinese scrolls brought to Japan by traveling Zen monks centuries earlier. The Emperor of Japan decorated him with the orders of the Rising Sun and the Sacred Mirror. In 1886 he sold the art collection he had amassed to Boston physician Charles Goddard Weld (1857-1911) on the condition that it go the the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. In 1890 he returned to Boston to be curator of the department of Oriental art at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. There Fenollosa organized the first exhibition of Chinese painting at the MFA in 1894 and developed the Department into a training center for generations of scholars. His public divorce and immediate remarriage to the writer Mary McNeill Scott (1865-1954) in 1895 outraged the Boston community, leading to his dismissal from the Museum in 1896. He was replaced by his student and fellow buying companion, Okakura Kakuzo (1862-1913). Fenollosa published Masters of Ukioye, a historical account of Japanese paintings and color prints which were exhibited at the New York Fine Arts Building, in 1896. In 1897 he journeyed back to Japan to be professor of English literature at the Imperial Normal School at Tokyo. After three years he returned to the United States to write and lecture on Asia. After his death, his wife compiled the two-volume Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art from his notes. His literary executor, Ezra Pound, compiled from notes and manuscripts, Cathay (1915); Certain Noble Plays of Japan (1916); and 'Noh', or, Accomplishment, a Study of the Classical Stage of Japan (1916). His last years were spent creating a collection for the Detroit railroad baron Charles Lang Freer, the basis of what is now the Freer Collection, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Fenollosa brought a curator's enthusiasm to the study of Asian art in the United States. He inspired Boston collectors to venture into the relatively new field of Far Eastern art, endowing the Boston Museum of Fine Art with one of the earliest and best Asian art collections in the United States. His books were widely read, but unfortunately are full of errors. Epochs, for example, was completed from notes after his death by his earnest, but less-knowledgeable, wife. The study of Japanese art in the United States was at such a dawning point that much information taken as correct by scholars has since been corrected. Assessments of Fenollosa's lasting contribution to the study of Asian art have varied greatly. Estimations that he both discovered the subject and that he made no important contribution to it exist. Fenollosa, together with Weld and another society physician-turned collector, William Sturgis Bigelow (1850-1926) formed what were known as the "Boston Orientalists."

Home Country: United States/Japan

Sources: Fenollosa, Mary McNeill. "Preface." Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art: an Outline History of East Asiatic Design. New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1912; Warner, Langdon. "Ernest Francisco Fenollosa." Dictionary of American Biography. vol. 6. New York: C. Scribner's sons, 1931, pp. 325-26; Kurihara Shinichi. Fuenorosa to Meiji bunka. Tokyo: Rikugei Shobo, Showa 43,1968; Chisolm, Lawrence W. Fenollosa: the Far East and American Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1963; Brooks, Van Wyck. Fenollosa and His Circle; with Other Essays in Biography. New York: Dutton, 1962; Tepfer, Diane. "Enest Fenollosa." The Dictionary of Art 10: 887; "Fun facts: 'The Boston Orientalists'. Boston Museum of Fine Art, http://www.boston.com/mfa/chinese/orientalist.htm .

Bibliography: Epochs of Chinese & Japanese Art: an Outline History of East Asiatic Design. New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1912; Instigations of Ezra Pound, Together with an Essay on the Chinese Written Character, by Ernest Fenollosa. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1920; 'Noh,' or, Accomplishment, a Study of the Classical Stage of Japan. New York: A. A. Knopf, 1917; East and West: The Discovery of American and Other Poems New York: T.Y. Crowell, 1893; The Masters of Ukioye: a Complete Historical Description of Japanese Paintings and Color Prints of the Genre School. New York: The Knickerbocker Press, 1896. (Dictionary of Art Historians)

Fenollosa, Ernest Francisco (18 Feb. 1853-21 Sept. 1908), educator, poet, and Orientalist, was born in Salem, Massachusetts, the son of Manuel Francisco Ciriaco Fenollosa, a Spanish musician who had come to the United States in 1838, and Mary Silsbee, who died when Ernest was eleven. After attending Salem High School, the sensitive and reserved young man entered Harvard College, where he studied with Charles Eliot Norton and founded Harvard's Herbert Spencer Club. He graduated first in his class in 1874 and was chosen class poet. He then began studies at Harvard Divinity School but did not take a degree. He became interested in the new "Art Movement" that was taking hold in Boston and in 1877 enrolled in classes at the newly opened school of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. In 1878 he married Lizzie Goodhue Millett, a childhood sweetheart from Salem; they had two children.

In 1878 Edward Morse, the marine archaeologist and Salem native, recommended Fenollosa for a teaching position in Japan. He joined Morse at Tokyo's Imperial University and began teaching political economy and philosophy, later adding logic and aesthetics. He remained at the university until 1886. Despite the general disrepute in which most Japanese held their traditional culture during the early Meiji Restoration push for modernization, Fenollosa quickly became interested in Japanese art. He began to campaign for its preservation, forming the Bijitsu-kwai (Art Club of Nobles) to restore national pride in traditional art and inspiring many Japanese artists to revive traditional practices. Fenollosa was particularly upset that Western artistic styles, rather than customary brush painting, were being taught in schools.

Fenollosa embraced Japanese culture. He became a Buddhist in 1885 and was formally adopted into the Kano family, known for its famous artists, taking the name Kano Yeitan, meaning "Endless Search." In 1887 he was appointed by the Japanese government to help form the Tokyo Fine Arts Academy and was sent to Europe and the United States to study methods of art education. The government also named him commissioner of fine arts and gave him the responsibility of registering all the art treasures of Japan, including temples. Fenollosa frequently instructed visiting Americans, among them Sturgis Bigelow, Henry Adams, John La Farge, Lafcadio Hearn, and Percival Lowell, on Asian art. With his visitors he made extensive tours of the countryside to unearth artifacts to purchase for their collections.

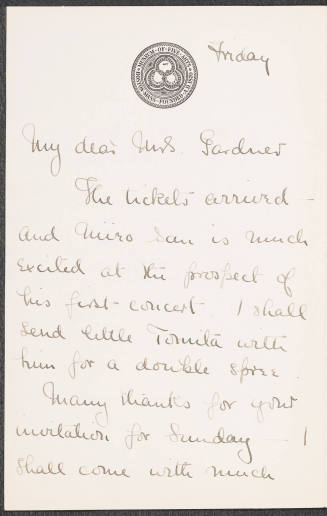

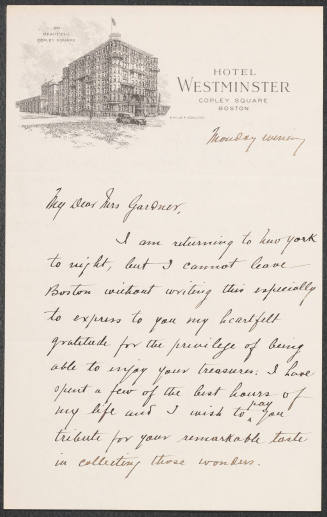

In 1890 Fenollosa and his family left Japan; upon their departure, the Japanese emperor told him, "You have taught my people to know their own art; in going back to your great country, I charge you, teach them also." Fenollosa fulfilled this command, returning to Boston to become the curator of the Museum of Fine Art's newly created Department of Oriental Art. His own collection of Japanese paintings had been bought in 1886 by Charles Gooddard Weld with the understanding that it would be donated to the museum and called the Fenollosa-Weld Collection. In Boston, Fenollosa became friends with Isabella Stewart Gardener and showed his collection of Japanese art to Bernard Berenson. As he had done in Japan, he tried to reform art education in the United States. Working with educator Arthur Dow, he designed a system of art education that moved away from hard-pencil drawing and the copying of shaded cubes and plaster figures--which Fenollosa derided as "tracing the shadow of a shadow"--and instead emphasized life, motion, color, impression, composition, and the synthesis of historical examples from many cultures. In 1892 he delivered a series of public lectures, which proved to be quite popular, and he continued to give lectures for the rest of his life. In 1893 he published East and West: The Discovery of America and Other Poems. He sat on the Fine Arts Jury for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois, and curated the Japanese display that, for the first time at an international exposition, was shown among fine arts rather than industries. In the early 1890s he also began advising Charles Lang Freer on his collection of Asian art, which Freer donated to the Smithsonian Museum in 1906.

In April 1896 Fenollosa resigned from his position at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, despite the fact that he had renewed his contract through 1897. This decision seems to have been prompted by his divorce from his wife in October 1895 and his rapid marriage to Mary McNeil, his assistant at the museum, two months later. In 1896 he returned to Tokyo with his new wife; the couple had no children. In contrast to his earlier experience in Japan, he now found many Japanese scholars intent on controlling their own artistic heritage. Consequently, his role in Japanese cultural life was limited. In the late 1890s he taught English at the Tokyo Normal School; studied Buddhism, Noh theater, and Chinese and Japanese poetry; and translated Japanese drama and Chinese poetry for Western audiences.

Fenollosa returned to the United States in 1900 to give a series of lectures, traveling across the country from California and settling in New York. During the last years of his life he worked on a comprehensive outline of Asian art, which was published by his widow in 1912 from his rough notes. The two volumes of Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art were unfortunately full of errors and ellipses the author had intended to correct in consultation with colleagues in Japan; despite the many mistakes in his work, he opened up areas of inquiry and thought that many followed. Fenollosa arranged his book by creative epochs rather than materials or industries; he took pains to show that Asian art was not static over time, as was frequently assumed by Westerners at that time. His goal was to emphasize what he called "the larger unity of effort underlying all art"; in the work of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century artists like James Abbott McNeill Whistler, he saw Eastern and Western art coming closer together. His poetry also described this union, which he saw as a double marriage of the West's masculine culture and feminine religion with the feminine culture and martial, masculine religion of the East. Van Wyck Brooks called him "a prophet of the idea of 'one world.' "

Fenollosa died in London, England, on the eve of his return to the United States after a holiday in Europe. His ashes, which were originally buried at Highgate in London, were moved to the temple grounds of Miidera in Kyoto, near where he had lived. After his death, his literary executor, Ezra Pound, published several books of poetry and drama from Fenollosa's notes and translations.

A prescient modernist, Fenollosa welcomed multiplicity and change in art and opposed the static absolutes of academic art. Through his collaboration with Arthur Dow, his ideas of line, color, and spacing transformed art education in the United States and influenced American art directly through Dow's most famous students, Max Weber and Georgia O'Keeffe.

Bibliography

Fenollosa's papers are held by the Houghton Library at Harvard University. In addition to the works mentioned above, he was the author of several catalogs of Japanese art, including The Masters of Ukioye (1896) and Catalogue of Hokusai (1901). Books edited by Ezra Pound from Fenollosa's notes are Cathay (1915), Certain Noble Plays of Japan (1916), and The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry (1936).

A brief account of his life is in Mary McNeil Fenollosa's preface to Ernest Fenollosa's posthumously published Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art: An Outline History of East Asiatic Design (1912). Laurence W. Chisolm's full-length biography, Fenollosa: The Far East and American Culture (1963), and Van Wyck Brooks, Fenollosa and His Circle with Other Essays in Biography (1962), place the scholar in his milieu. Seiichi Yamaguchi, On and after the Death of Ernest Fenollosa (1976), is drawn mostly from letters between Mary McNeil Fenollosa and Charles Lang Freer. Dorothy Hook has written on Fenollosa's educational reforms, "Fenollosa and Dow: The Effect of an Eastern and Western Dialogue on American Art Education" (Ph.D. diss., Pennsylvania State Univ., 1987).

Bethany Neubauer

Back to the top

Citation:

Bethany Neubauer. "Fenollosa, Ernest Francisco";

http://www.anb.org/articles/17/17-00277.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 14:35:21 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Boston, 1850 - 1926, Boston

Portland, Maine, 1838 - 1925, Salem, Massachusetts

Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1881 - 1955, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Japan, 1890 - 1976, Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts