Lady Gregory

Roxborough, Ireland, 1852 - 1932, Coole, Ireland

Marriage, Coole Park, and early writing

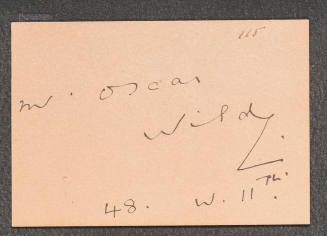

On 4 March 1880, at the age of twenty-eight, when it had seemed she would remain a spinster, Augusta Persse married Sir William Henry Gregory (1816–1892) of neighbouring Coole Park. Gregory, thirty-five years her senior, had recently retired as governor of Ceylon, and enjoyed a high reputation in Irish and English political and social circles for his personability and cultivation, counting figures such as Robert Browning, Tennyson, and Henry James among his friends. Despondent since the death of his first wife in 1873, Gregory seems to have remarried primarily in search of an intelligent companion for his old age, but he soon recognized and encouraged the potential Augusta Persse displayed. The marriage transformed her life, introducing her to prominent literary and political society in London where they lived part of each year, to progressive social and religious views, and to extensive foreign travel, and she flourished in her new milieu, quickly earning a reputation as a hostess, conversationalist, and thinker. Yet if the twelve years of her marriage were, as she acknowledged, a ‘liberal education’ (draft memoirs, Berg MSS), they were also confiningly conventional in many respects, and she was expected to follow Gregory's interests dutifully and to endure repeated separations from their one child, Robert, born in 1881, to satisfy her husband's penchant for travel. Though she would wear mourning black for the forty years of her widowhood, her diaries and autobiographical writings suggest some disappointment at the marriage's limitations, a disappointment registered also in her brief clandestine affair with poet and anti-imperialist Wilfrid Scawen Blunt (1840–1922) in 1882–3. Her shared enthusiasm with Blunt for the Egyptian nationalist leader Arabi Pasha inspired her first significant publication, ‘Arabi and his household’, an essay printed in The Times in 1882 and subsequently as a pamphlet. The Irish land war of the early 1880s compounded this first political awakening, and in ‘An emigrant's notebook’, a series of unpublished autobiographical sketches written in 1883, she began to reflect sustainedly on Irish culture, ascendancy rule, and her own identity. The challenge to landlord power posed by the 1886 Home Rule Bill and the rise of Parnell further heightened her self-consciousness of her uneasy position as a landlord. Short stories written around 1890 show her negotiating the tensions between her staunchly protestant, ascendancy views and her love of the Irish country people. Drawing closely on her personal experiences, they use the distinctive Clare–Galway idiom of her tenants for literary purposes well before her development of ‘Kiltartan’ speech under the influence of Hyde and Synge a decade later. The promise of such early writings, though, was not fully realized during the marriage, during which wifely and maternal duties took priority. Paradoxically, while marriage was the essential step into a world of intellect and social standing without which her subsequent achievement would not have been possible, it was only Sir William's death in 1892 and the demands of widowhood that brought her to the independence necessary for a distinctive creative voice.

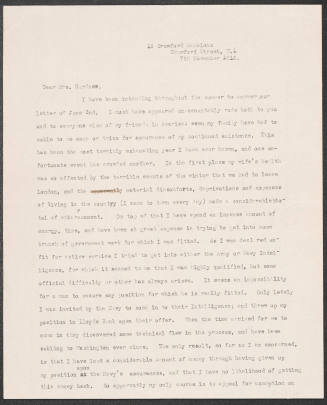

Left £800 a year in estate income, but anticipating land reform and with Coole already encumbered, Lady Gregory retrenched by selling their London house and living in Ireland. There, her desire to write and her need to reassess her personal situation began to coincide more productively. A Phantom's Pilgrimage, an attack on Gladstone's 1893 Home Rule Bill, displays and explores a significant tension between her self-interest as a Unionist and her recognition of the needs of Catholics, nationalists, and the Irish peasant class. Its underlying debate as to where her cultural loyalties should lie continued and developed as she edited her husband's autobiography (published 1894), and then Mr Gregory's Letter-Box (published 1898), the political papers of his grandfather, under-secretary of Ireland, 1813–31, both of which projects involved sustained reflection on the course of nineteenth-century Irish politics. When a ‘tendency to Home Rule’ was noted in her commentaries in the latter volume, she declared that it was impossible to study Irish history ‘without getting a dislike and distrust of England’ (Gregory, Our Irish Theatre, 41). She was also becoming progressively more aware of the growing literary movement in Ireland, having read and admired Yeats's The Celtic Twilight prior to first meeting him briefly in 1894, and having begun, under its influence, to investigate folklore herself.

Yeats, Irish nationalism, and folklore

When Yeats came to stay as a guest of her neighbour Edward Martyn in August 1896, Lady Gregory was thus well advanced on the road to Irish nationalism, and, as she later wrote, her ‘energy was [already] turning to’ literature (Seventy Years, 390). Seeking Yeats out, she immediately asked if he could set her to some work in the literary movement. The friendship was cemented when they next met in spring 1897 in London, where she hosted him at a series of dinners, introduced him to influential friends, and gave him the folklore she had gathered that winter. Yeats, at a low point financially and emotionally, and, as his father had observed in 1896, never able to ‘work alone’ or without the ‘sympathy’ of a friend (Murphy, 192), was disarmed by and receptive to her energetic and determined wish to manage and nurture him. She in turn was ready to lionize and support the young poet, acknowledging later that ‘the achievement of a writer’ was the one for which she had long had ‘most admiration’ (draft memoir, Berg MSS). But she was also shrewdly conscious of the specific benefits such a friendship might confer, both in furthering her connection with the world of nationalism, and in providing an outlet for her creative energies. She was, moreover, herself disposed towards working in partnership rather than alone. Throughout her life she would remain caught in a tension between the need to assert herself creatively and the ingrained imperatives of womanly self-sacrifice Roxborough had encouraged, a tension heightened by the widespread antipathy to female enterprise in the Ireland of her time. Prior to meeting Yeats, she had defined her few creative initiatives in terms of service to her family, to her husband, and briefly to Wilfrid Blunt, roles which certainly protected her from seeing herself or being seen as transgressively ambitious, but which also severely limited her opportunities for individual achievement. Working with, for, and through Yeats, however, provided her with a role in which self-fulfilment and duty were also not in apparent conflict, but which offered her real creative scope. For the remainder of her literary career she would define her efforts in terms of service to Yeats, to Ireland, to the Abbey Theatre, or to the country people of Galway, thereby downplaying, at least publicly, the force of her underlying determination.

In July 1897 Yeats came to Coole for the first of twenty consecutive long summer stays, and Lady Gregory at once helped to make his long-harboured ideas of founding an Irish dramatic movement a reality by offering the first monetary guarantee for the Irish Literary Theatre and persuading friends to underwrite most of the remainder needed. Short seasons of plays were produced in Dublin in 1899, 1900, and 1901, paving the way for the founding of the Abbey Theatre in 1904, of which Lady Gregory became patentee and co-director. They also began to gather folklore together, resulting in a series of long articles and a revised and extended edition of The Celtic Twilight (1902), in which her hand and influence are manifest. Her independent work developed in tandem with her efforts for Yeats, and between 1897 and 1901 she published some three dozen short articles, essays, and letters, mainly on folklore. She also quickly demonstrated her considerable abilities as an organizer promoting literary and nationalist causes, and as a hostess, making Coole both a retreat for Yeats and recognized as a creative centre for most of the prominent Irish literary figures of the time, including George Moore, J. M. Synge, Douglas Hyde, and, later, George Bernard Shaw and Sean O'Casey, most of whom engaged in significant creative, and often collaborative, work while there. From around late 1897 she began to support Yeats with cash and gifts of furniture, clothing, and food, thereby allowing him to do less journalism for money and focus instead on his creative work. Her patronage was substantial for several years, and Yeats eventually repaid her £500 in 1914. By 1898 the friendship had become crucial to both writers emotionally as well as artistically and practically, and although an element of formality always lingered between them—signalling their shared sense that creative responsibilities must always take priority—for the next two decades they were each other's closest counsel, with Yeats memorably articulating the complex bonds between them in 1909 when he wrote ‘She has been to me mother, friend, sister and brother. I cannot realize the world without her’ (Yeats, Memoirs, 160–61).

From around 1901 on Lady Gregory began to pursue her own creative opportunities even more energetically. Her redaction of the Táin bó Cúailnge, published in ‘Kiltartan’ English as Cuchulain of Muirthemne (1902), was fulsomely praised by Yeats as the best Irish book of his time, and became a vital source of legendary and imaginative material for him, as did her Gods and Fighting Men (1904), a retelling of the Fianna legends. In seeking popular readership for these books, she suppressed or modified violent and sexual elements in the source tales, while also emphasizing their heroic and ideal elements as part of her avowed aim to bring ‘dignity’ to Ireland. These translations became her best-selling prose works, though their ‘Kiltartan’ idiom is now usually regarded as stylistically limited.

The Abbey and writing for the theatre

More surprising was Lady Gregory's sudden emergence, at the age of fifty, as a dramatist. Having assisted Yeats secretarially on his plays, she gradually assumed ever greater direct responsibility in his work, co-authoring Cathleen ni Houlihan with him in 1901, and Where there is Nothing in 1902, and then contributing substantially to all his other non-verse plays of that decade. Yeats had initially sought her help merely to supply peasant dialogue and realist folk details to offset his own tendency to symbolism, but their creative exchanges quickly developed into a more complex stylistic, ideological, and imaginative interdependence. Claiming that more plays, and particularly comedies, ‘were needed’ for the theatre movement (Gregory, Our Irish Theatre, 53), she wrote some three dozen works of her own between 1902 and 1927, displaying particular skill with tightly constructed one-act dramas. Comedies such as Spreading the News (published 1905), Hyacinth Halvey (1906), and The Jackdaw (1909) became staples at the Abbey as short companion pieces for works of peasant realism or tragedy, but her most powerful one-act plays are typically those in which a political component animates the action, such as The Rising of the Moon (1904), The Workhouse Ward (1909), and The Gaol Gate (1909). As in her folklore volumes Poets and Dreamers (1903) and The Kiltartan History Book (1909, expanded 1926), her focus in these ‘political’ plays is on the beliefs and rituals which sustain community and which allow individuals to assert themselves in the face of oppression or poverty. In longer plays she explored Irish history more directly, but here too her creativity seems to have been most animated in dealing with legendary figures who displayed some exemplary form of strength of character—notably, female figures, in Dervorgilla (1908) and Grania (1912)—than in treating conventionally pivotal moments in Irish history such as in Kincora (1905). Her later work is progressively more invested in myth-making functions, with plays like The Image (1910) which centred on the transformative power of a hidden ‘heart secret’.

Styled ‘the greatest living Irishwoman’ and ‘the charwoman of the Abbey’ by Bernard Shaw (Laurence and Grene, xxv, 66), Lady Gregory became the most tenacious champion of the theatre she had helped Yeats found, campaigning for funds, touring with and promoting the Abbey company in England and America, and encouraging younger writers (though also earning the resentment of others who felt their merits had been ignored). Sean O'Casey credited her encouragement and advice as crucial to his emergence as a writer in the 1920s, though their close friendship was permanently damaged by the Abbey's rejection of The Silver Tassie in 1928. Her 1913 history, Our Irish Theatre, a somewhat self-serving and partisan account of the inception and development of the Abbey, powerfully conveys her tactical shrewdness, determination, and excitement in defending the theatre during crises such as the controversies over Synge's Playboy of the Western World (1907) and Shaw's Shewing-up of Blanco Posnet (1910). She openly acknowledged that Yeats's interests always came first for her at the Abbey, thereby generating resentment in Synge and others, but she was also often charged with using her directorial position to promote her own work. In the theatre's first two decades, her plays were indeed the most frequently performed of any author's, but they were also, particularly in the early years, the most consistently successful at the box office.

Losses and later life

At her peak of influence just prior to the start of the First World War, Lady Gregory thereafter suffered a succession of sapping blows. The death of her nephew Sir Hugh Lane on the Lusitania in 1915 began the long legal controversy over paintings he left to Ireland in an unsigned codicil to his will, and she spent much of her energy for the remainder of her life fighting an ultimately unsuccessful battle to win Ireland's claim. Robert's enlistment in 1915 left her constantly anxious, and his death in 1918 as an airman on the Italian front was a loss from which she never recovered. Her later ‘wonder’ plays such as The Golden Apple (1916) and The Dragon (1920) take on fantastic and otherworldly mythic structures as their subject matter, as if following her own observation that peasant lore typically became richer in proportion to the poverty or difficulty from which it emerged. A mystical and religious element becomes more pronounced in plays such as The Story Brought by Brigit (1924) and Dave (1928). Yeats's marriage in 1917 also inevitably reduced her long-held position of primacy in his life. His time spent at Coole diminished, although their friendship was left unshaken, and Visions and Beliefs in the West of Ireland, the folklore project they had begun together in the 1890s, appeared in 1920. She worked sporadically on an autobiography from late 1914 until the early 1920s, but withheld it from publication as unsatisfactory, and its narrative symptomatically closes with distraught chapters on the war, the 1916 rising, and Robert's death. Her final draft, Seventy Years, was eventually published in 1974.

During the Anglo-Irish War and the civil war which followed the Anglo-Irish treaty (1921) Lady Gregory was a horrified but perceptive spectator at Coole, recording events in her substantial Journals (published 1978 and 1987). Her expanded Kiltartan History Book (1926), a significant pioneering work in the field now termed contemporary folklore, embodies country people's responses to the recent conflicts, and reflects her own increasingly controlled response to the cultural shifts taking place and to her own losses. Although increasingly republican in her sympathies, she was aware that her position was marginal within the new Irish state for which she had worked so long, and when nominated for a senate seat in 1925 she declined to campaign and fell well short of election. Unlike so many ascendancy houses, Coole survived the troubles, but land reform had by the 1920s reduced the estate's viability, and her right to life tenure there under the terms of her husband's will had in any case become ambiguous after Robert's widow assumed ownership in 1918. Following several smaller sales, the remainder of the estate was sold to the Irish ministry of lands, and maintained by the forestry department, with Lady Gregory remaining as a tenant in the house (which was demolished in 1942). Determined not to risk a fall-off in the quality of her work, she published her Last Plays in 1928, reserving her final energies for Coole (1931), an elegy for the Gregory family, Coole Park, and her own part in its final flowering. Recognizing her decline, Yeats, who spent much of her last year with her at Coole, responded by contributing ‘Coole Park’ (later ‘Coole Park, 1929’) as the opening poem for the volume, and then writing ‘Coole and Ballylee, 1931’, his most elaborate celebrations of their long partnership, her formidable character, and powerful influence. Operations for breast cancer in 1923, 1926, and 1929 were only temporarily successful, but she declined further surgery, enduring increasing pain and disability over her last two years of life, and refusing to the end to take any pain-killing drugs that might affect her mind. Lady Gregory died at Coole on 22 May 1932, and was buried at Bohermore cemetery in Galway city.

James L. Pethica

Sources

letters, diaries, draft memoirs, and other materials, NYPL, Berg collection · unpublished letters, diaries, draft memoirs, and other materials, Emory University, special collections · unpublished letters, diaries, draft memoirs, and other materials, NL Ire., Gregory MSS · unpublished letters, diaries, draft memoirs, and other materials, priv. coll. · Lady Gregory, seventy years, 1852–1922: being the autobiography of Lady Gregory, ed. C. Smythe (1974) · Lady Gregory's journals, ed. D. Murphy, 2 vols. (1978–87) · Lady Gregory's diaries, 1892–1902, ed. J. Pethica (1996) · Lady Gregory [I. A. Gregory], Coole (1971) · Lady Gregory [I. A. Gregory], Our Irish theatre (1972) · Lady Gregory: fifty years after, ed. A. Saddlemyer and C. Smythe (1987) · E. Coxhead, Lady Gregory: a literary portrait (1967) · Burke, Gen. Ire. (1976) · Lady Gregory [I. A. Gregory], Sir Hugh Lane: his life and legacy (1974) · W. B. Yeats, Memoirs, ed. D. Donoghue (1972) · W. B. Yeats, Autobiographies (1955) · D. H. Laurence and N. Grene, eds., Shaw, Lady Gregory and the Abbey (1993) · W. M. Murphy, Prodigal father: the life of John Butler Yeats (1978) · CGPLA Éire (1932) · personal knowledge (2004)

Archives

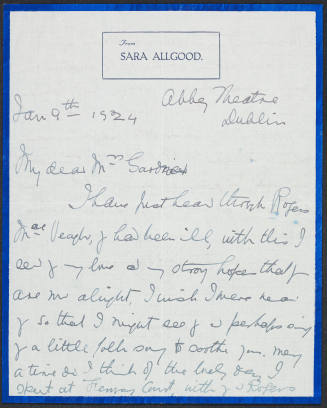

Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, papers · Ransom HRC, papers :: BL, corresp. with the Society of Authors, Add. MS 56717 · BL, corresp. with George Bernard Shaw, Add. MS 50534 · FM Cam., letters incl. MS poems to Wilfrid Scawen Blunt · NYPL, Berg collection, corresp. and literary MSS · NYPL, Quinn collection, papers · Sligo County Library, Sligo, corresp. with Sara Allgood · Southern Illinois University, corresp. with Lennox Robinson · TCD, corresp. with Thomas Bodkin · TCD, corresp. with Mary Childers · TCD, corresp. with J. M. Synge · U. Glas., special collections department, letters to D. S. MacColl

Likenesses

J. B. Yeats, oils, 1903, NG Ire. · W. Orpen, group portrait, pen-and-ink caricature, 1907, NPG · A. Mancini, 1908, Hugh Lane Gallery of Modern Art, Dublin · J. Epstein, bronze bust, 1910, Hugh Lane Gallery of Modern Art, Dublin · F. Lion, lithograph, 1913, NPG · G. Kelly, oils, c.1914, Abbey Theatre, Dublin · W. Orpen, oils, NG Ire. [see illus.] · G. Russell, drawing, Abbey Theatre, Dublin · T. Spicer-Simson, bronze medallion (after his plasticine medallion), NG Ire. · T. Spicer-Simson, plasticine medallion, NG Ire. · J. B. Yeats, drawing, Abbey Theatre, Dublin · J. B. Yeats, pencil sketch, repro. in Samhain (Dec 1904); copy, NYPL · photograph, repro. in Seventy years, ed. Smythe, cover; priv. coll. · photograph, repro. in Murphy, ed., Lady Gregory's journals, 2, cover; priv. coll. · photographs, priv. coll.

Wealth at death

£4809 3s. effects in England: probate, 21 Nov 1932, CGPLA Eng. & Wales · £746 19s. 3d.: probate, 16 Sept 1932, CGPLA Éire

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

James L. Pethica, ‘Gregory , (Isabella) Augusta, Lady Gregory (1852–1932)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2006 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2113/view/article/33554, accessed 8 Aug 2013]

(Isabella) Augusta Gregory (1852–1932): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33554

[Previous version of this biography available here: May 2005]

LC name authority record n 80056886

LC Heading: Gregory, Lady, 1852-1932

Birth/death locations verified through Irish Writers Onlne (irishwriters-online.org, accessed 14 May 2015)

Augusta, Lady Gregory (Isabella Augusta, Lady Gregory (15 March 1852-22 May 1932), born Isabella Augusta Persse, was an Irish dramatist, folklorist and theatre manager. She co-founded the Irish Literary Theatre and the Abbey Theatre, and wrote numerous short works for both companies.(LC name authority record n 80056886)

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

County Longford, Ireland, 1881 - 1972, Enfield, Connecticut

Paisley, Scotland, 1855 - 1905, Syracuse, Sicily

Black Bourton, England, 1768 - 1849, Edgeworthstown, Ireland