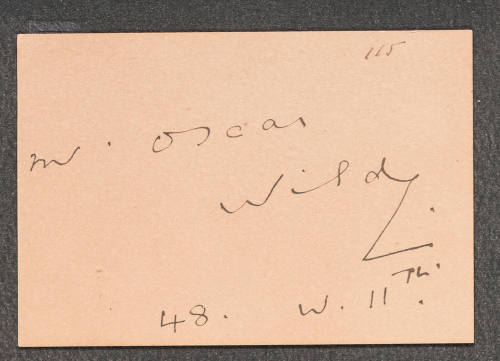

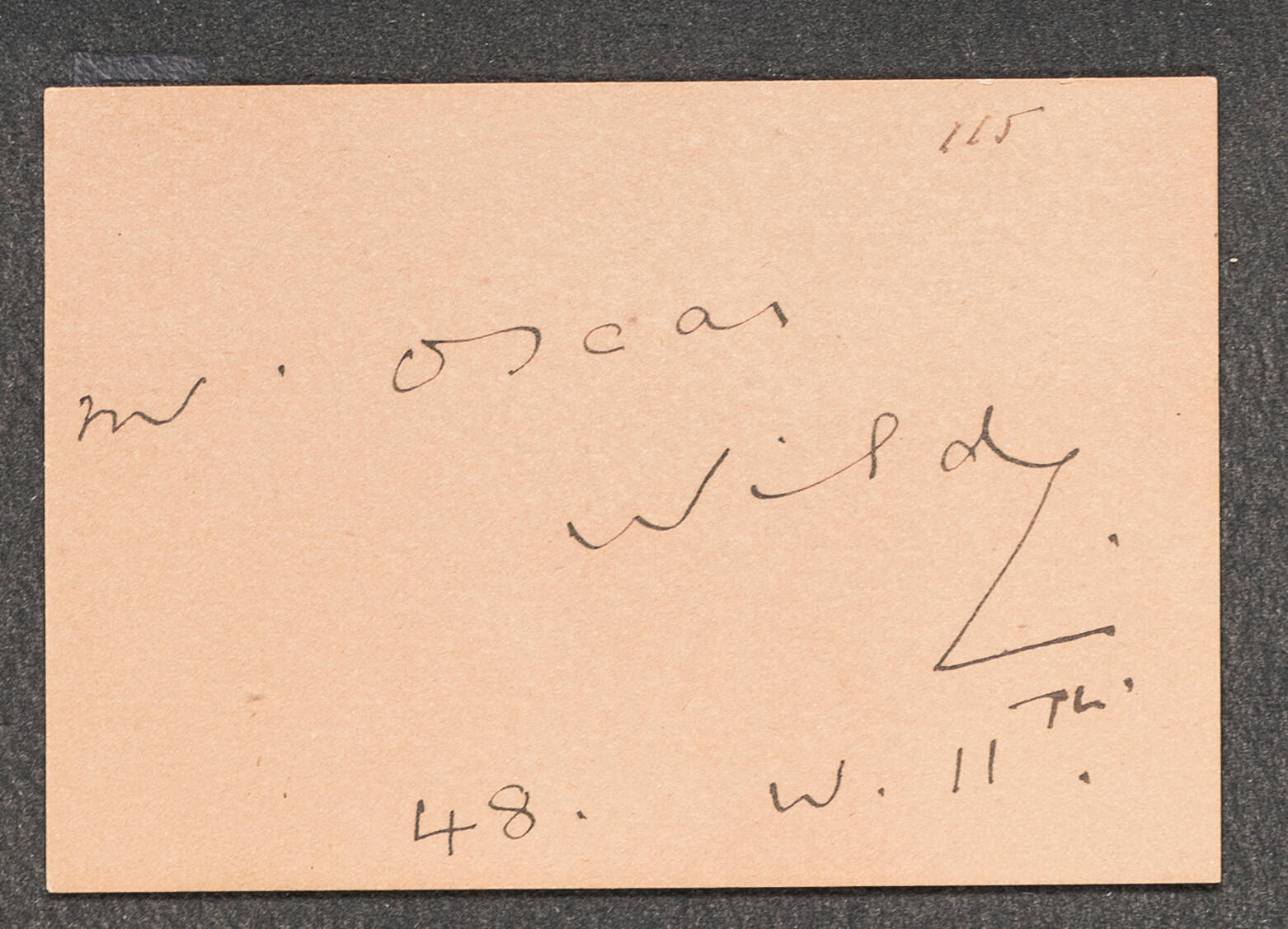

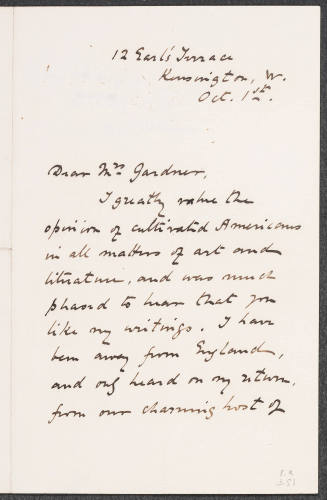

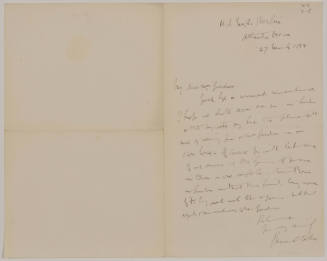

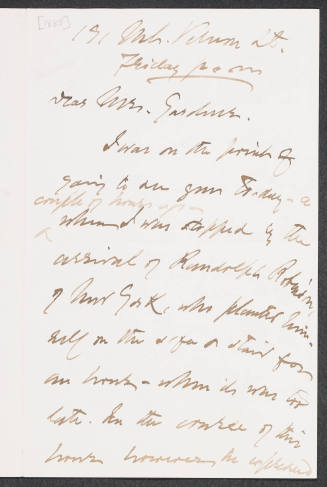

Oscar Wilde

Dublin, 1854 - 1900, Paris

LC name authority:n79042038

LC Heading: Wilde, Oscar, 1854-1900

Biography:

Wilde, Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills (1854–1900), writer, was born on 16 October 1854 at 21 Westland Row, Dublin, the second of the three children of William Robert Wills Wilde (1815–1876), surgeon, and his wife, Jane Francesca Agnes Wilde, née Elgee (1821–1896), writer and Irish nationalist, daughter of Charles Elgee (1783–1824), solicitor, and his wife, Sarah Kingsbury (d. 1851), whose sister Henrietta married the Revd Charles Robert Maturin (1780–1824), author of Melmoth the Wanderer (1820). Wilde, his father, and his elder brother, William Charles Kingsbury (1852–1899), afterwards added the name Wills as a forename, asserting kinship to William Gorman Wills, a playwright famous after Henry Irving's title-role performance of his Charles I (1872). Wills was the son of the Revd James Wills (1790–1868), poet and man of letters, whose The Universe (1821) was wrongly attributed to his friend Maturin, thus symbolizing linkage between the Wilde and Elgee families.

Boyhood and education, 1854–1874

Wilde's immediate family was more clerical than any of his fellow writers' of the Irish Renaissance: in addition to Maturin, two paternal uncles proper and one by marriage, a maternal uncle, and maternal grandfather were ordained in the (established) Church of Ireland. These and some of their lay relatives and friends participated in the Romantic flowering of Irish evangelicalism (1815–45) which sought to convert the Irish Catholic masses where predecessor protestant episcopalians were content to subordinate them. All the major Irish Renaissance writers of protestant origin showed some evangelical inheritance, substituting cultural for spiritual leadership: Wilde, Shaw, Yeats, Synge, O'Casey. All retained the self-confidence and authoritarianism of Irish protestant evangels. Wilde's Iokanaan in Salomé (1893) and Canon Chasuble in The Importance of being Earnest (1895) reflect that family clerical background, as do Wilde's ‘Poems in Prose’.

Wilde was baptized by his father's brother Ralph in St Mark's Church, Dublin, on 26 April 1855. Five or six years later he was baptized into the Roman Catholic church, at his mother's instance, by the Revd L. C. Prideaux Fox (1820–1905), chaplain to the juvenile reformatory at Glencree, co. Wicklow, where the family were on holiday. Wilde violated no Irish protestant taboo as great as that broken by his mother for him in thus perverting him (as her relatives would have termed it). During the great Irish famine (1845–52) William Wilde had directed the census from local medical reports giving him unique mastery of famine mortality and his folklore researches showed its cultural toll, while Jane Elgee as poet and polemicist on the Dublin Nation declared that the million-odd victims owed their fate to her fellow protestant landlords. Wilde's dialogue between Death and Avarice in ‘The Young King’ (Lady's Pictorial, Christmas 1888) echoes her indictment while his Ballad of Reading Gaol (1898) has recollections of her poem ‘The Famine Year’. He would have understood the symbolism of her consecration of her sons to the church whose children had died in such horror and such numbers. He reaffirmed her defence of the Irish revolutionaries of 1848 when lecturing in San Francisco in 1882. Filial devotion made him a rebel, with some uncertainty as to his cause.

Wilde's Irish-speaking father took his family on vacations to Galway in quest of folklore, later written up by his widow: Wilde himself retained enough Irish to sing abstruse Gaelic lullabies to his children. Wilde would also draw on his parents' mastery of ghost, curse, and fairy lore to inspire his first prose fiction, ‘The Canterville Ghost’ and ‘Lord Arthur Savile's Crime’ (Court and Society Review, Feb–March and May 1887), and The Happy Prince and other Tales (1888). The wish of human vanity whose fulfilment brings ultimate damnation, characteristic in Gaelic story-telling, dominates Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890, 1891). Wilde would duly win his greatest social success as oral narrator. His parents' choice of Gaelic heroic names for him (including what may have been a claim of descent from the ‘wild’ O'Flaherties, memorable threats to English settlers) heightened his alienation. Fenian legend supposedly survived in the bard Ossian, son of the Odysseus-like contriver Fingal, and father of the Achilles-like hero Oscar: Wilde fulfilled all three roles in his life. But Fenian names sounded ominous in Irish protestant ears after 1858, and Wilde may have suffered from it as a boarder at Portora Royal School, Enniskillen, co. Fermanagh, a bastion of English imperial culture where Ireland was virtually obliterated from formal educational allusion. Wilde seems to have detested his time there (1864–71), although winning scripture prizes in 1869 and 1870. But it taught him how to conceal the Irish identity he had inherited.

On 23 February 1867 Wilde was told that his little sister Isola Francesca (b. 1857) had just died. He mourned her unconsolably, memorialized her ten years later in the poem ‘Requiescat’ (later anthologized by Yeats), carried a lock of her hair as best he could until his death, and haunted his literary work with images of girls unknowing of their incipient womanhood, for example in Vera (1880, 1882), ‘The Canterville Ghost’, ‘The Birthday of the Infanta’ (Paris Illustré, 30 March 1889), The Picture of Dorian Gray, each of his four great comedies, and Salomé, the keynote always innocence expressed in extreme terms, whether of courage, kindness, or cruelty. His earliest surviving letter (to his mother, 5 September 1868) shows his hunger at Portora for home and its culture, asking for the current number of James Godkin's National Review, then an outlet for her patriotic verse, and seeking news of her poems' possible republication (subsequently realized) by the Glasgow Irish nationalist firm Cameron and Ferguson. From Portora he won a scholarship to Trinity College, Dublin, in 1871.

Wilde's mother by now held a literary salon at 1 Merrion Square, Dublin, the Wilde family home from 1855, with visitors such as the poets Aubrey de Vere and Samuel Ferguson, the great peasant story-teller William Carleton, and the Dublin historian John Gilbert. At Trinity, Wilde's chief mentors were the classicists John Pentland Mahaffy and Robert Yelverton Tyrrell. Mahaffy proved a stimulating challenge in his witty contempt for Roman Catholicism, Irish nationalism, democracy, liberalism, socialism, and Gaelicism, on none of which he influenced Wilde: but both men helped make him a great Greek scholar. He won a foundation scholarship in 1873 and the Berkeley gold medal for Greek in 1874. Mahaffy germinated Wilde's first great dramatic character, Prince Paul Maraloffski, the tsar's premier in Vera, cruel, treacherous, and endlessly amusing. Wilde's juvenile cult of Shelley weathered the editorial austerity exuded by Edward Dowden from Trinity's chair of English literature. Wilde was then too shy for much student friendship but activity in college societies threw him together with Edward Carson.

Poet and intellectual in Oxford, 1874–1879

In June 1874 Wilde won a demyship in classics to Magdalen College, Oxford, where he studied until 1879, having graduated BA in November 1878 with a double first in classical moderations and literae humaniores or Greats (classics). Dublin probably educated him better than Oxford, but Oxford gave him a new world of expression and audience. In place of the Dublin wits and scholars vying to outsmart one another, he found intellectuals whose oratorical articulacy was declining as his own developed: Walter Horatio Pater and John Ruskin. In Wilde's last Dublin year Pater published his Studies in the History of the Renaissance. Its conclusion induced academic malice and was withdrawn by him in the second edition (1877), but Wilde was fascinated by its agenda: ‘not the fruit of experience, but experience itself ... success in life ... [is] to burn always with this hard gemlike flame’ (W. Pater, Studies in the History of the Renaissance, 1873, 210). Ruskin recruited Wilde into a group of social activists trying to build a road, and his anger at social cruelty found fallow soil in the boy from the famine-writers' house. Pater and Ruskin shaped Wilde's thought and its expression: they did not originate it. Initially he brought their ideas and his glosses into the market place in lectures on aesthetics in the UK and the USA. Thereafter he embedded them, begirt in his own wit and charm, in fictions such as The Happy Prince and other Tales and The Picture of Dorian Gray. To Wilde ideas had to assert themselves dramatically: Yeats saw him as ‘a man of action’ (O'Sullivan), Chesterton as ‘an Irish swashbuckler—a fighter’ (The Victorian Age in Literature, 1913), and even Whistler's sneer ‘Oscar has the courage of the opinions—of others’ (Truth, 2 Jan 1890) realized it.

Wilde's first literary stage was Irish, finding outlets for his Oxonian perceptions in poetry and prose in the Dublin University Magazine (protestant evangelical), Kottabos (edited by Tyrrell), the Irish Monthly (Jesuit), and the Boston Pilot (Catholic and Irish nationalist). He celebrated the new temple of aesthetic rebellion, the Grosvenor Gallery (Dublin University Magazine, June 1877), and made a lengthy appeal for a starving Irish artist Henry O'Neill (1800–1880) in Saunders's News-Letter (29 December 1877), reprinted in his mother's old Dublin journal, The Nation. David (later the Rt Revd Abbot Sir David) Hunter-Blair (1853–1939), a close friend at Magdalen, was converted to Roman Catholicism in 1875, graduated in 1876, and entered the Benedictine order in 1878. Wilde's Catholic self was most notably expressed to him, although Wilde deferred a full Catholic identity until his deathbed (D. H. Blair, In Victorian Days, 1939). Wilde's Catholic consciousness permeates his stories, his prison and post-prison writings pursue its realization, and his poem The Sphinx (1894), begun at Oxford, shows warring attractions for him of paganism and Catholicism.

Wilde was happy at Oxford, apart from financial pressures and disciplinary measures following his protracted vacation in Greece in April 1877 with Mahaffy. Sir William Wilde's death on 19 April 1876 was a severe psychological blow, and left the family much poorer than they had expected. Wilde won Oxford's Newdigate prize for his poem ‘Ravenna’ in 1878 and declaimed it in the Sheldonian Theatre on 26 June. It was published as his first book. Its laments for the sufferings of Dante and Byron proclaimed admiration and anticipation. His graduation was delayed by the requisite divinity test to satisfy requirements as to his Anglican status, which he deliberately failed until it was a laughing-stock. He then worked on ‘Historical criticism among the Ancients’, for the chancellor's English essay prize. No award was made. Posthumously published as The Rise of Historical Criticism (1909) it shows a remarkable grasp of historiography, a subject then in its infancy. It shows history as the foundation of his thought, with a judicious scepticism. It also stands on the cusp of Victorian confidence and its collapse. It sees history's motive as ‘the discovery of the laws of the evolution of progress’ (O. Wilde, Complete Works, introduced by M. Holland and others, [1994], 1207). Its author's doubts about whether history was progress grew to illuminate works as different as his The Importance of being Earnest and The Ballad of Reading Gaol.

Literary apprentice, dandy, and lecturer at large, 1879–1885

Wilde settled in London early in 1879; his mother and brother also moved there. The land war developing in Ireland made their few remaining properties uneconomic, but Oscar and his mother were none the less firm supporters of home rule and Charles Stewart Parnell. They still cut a wide swathe in society, assisted by her new salon. He won friendships with three great rivals in beauty and celebrity in and out of the theatre, Emily Charlotte Le Breton (Lillie) Langtry, Ellen Terry, and Sarah Bernhardt, writing poems to all three. He frequented the theatre and dressed in the aesthetic role, the better to evangelize beauty in modern life. The knee-breeches, the great bow-ties, and the ornate hats became famous; they were guyed and caricatured in Punch and bad plays and ultimately in the new Gilbert and Sullivan opera Patience, for whose opening on 23 April 1881 Wilde bought a 3 guinea box. He knew their work, and he intended not to protest against its satire on aestheticism, but to latch on to it. His physique, mannerisms, opportunism, salesmanship, female admirers, and even background of Irish landholding inspired George Grossmith as Bunthorne to put more and more of Wilde into the part. Wilde, tall, growing plumper, drawling, almost affecting affectation, developed his own performance on Bunthorne lines. Unlike Bunthorne, Wilde was not a fraud: he was fascinated by beauty from classicism to Keats, he correlated reform in dress and house decoration with beauty and respect in human relations, and he saw philistinism as tyranny in taste and politics. But he enjoyed self-mockery—from his difficulty at Oxford in living up to his blue china to his deathbed insistence that the wallpaper was killing him. His Poems were published by David Bogue at his own expense a few weeks after Patience opened, and like Bunthorne's they were often derivative (for which the Oxford Union, despicably, rejected his presentation copy). The book sold out four editions of 250 copies at half a guinea within the year. Amid much that had been tried, there was a little that rang true—‘Requiescat’, ‘Magdalen Walks’, ‘Hélas!’, ‘Humanitad’, respectively saluting Isola, Oxford, Christianity, paganism. Many of the poems have a value as social documents—giving us incisive glimpses of the theatre, politics, cosmopolitanism, and parochialism of their time. Gladstone, Matthew Arnold, Swinburne, and Oscar Browning complimented him on all or some of the poems, but reviewers were rude. Individual verses acquired new meanings in the light of his later life, such as ‘Roses and Rue—to L[illie] L[angtry]’:

But strange that I was not told

That the brain can hold

In a tiny ivory cell,

God's heaven and hell.

Yet Wilde's tragic forebodings were constantly balanced by the growth of his comic genius. His tragedy Vera found its early drafts undermined by the hilarity induced by the evil Prince Paul's epigrams. Wilde had studied Polish and Russian literature under his mother's influence, but Vera's hidden Irish resonance, however smothered by the tsar's court and its pursuing nihilists, gave the hardbitten worldly wisdom on which the play turns. The play argued, wisely from either Irish or Russian contexts, that political intransigence ensures worse repression and worse revolution, and that political extremes induce one another's success at the expense of rational solutions. Vera was scheduled for a London production in December 1881 with Mrs Bernard Beere, née Fanny Mary Whitehead (1856–1915), a lifelong friend of Wilde, in the title role but it was cancelled since its nihilist assassination of the tsar might seem to reflect on its real-life counterpart the previous March, the murder of Tsar Alexander II.

Wilde contracted with the producer of Patience, Richard D'Oyly Carte, to lecture in the USA, whose people might otherwise fail to understand what the opera was satirizing. He sailed on the Arizona on 24 December 1881, landing in New York on 2 January 1882, delivering nearly 150 lectures throughout the USA and Canada, and receiving $6000 over the next twelve months. His lectures were entitled ‘The decorative arts’, ‘The house beautiful’, ‘The English Renaissance’, and ‘Irish poets and poetry in the nineteenth century’. He improved in both brevity and force as he travelled from the east to the west coast. He sailed home on the Bothnia on 27 December 1882, docking in Liverpool on 6 January 1883. His was a theatre performance, and it furthered theatre links. His friendship with Dion Boucicault guided the early weeks of his tour and gave him contacts for Vera. Boucicault proved in his case as in those of all his major fellow playwrights of the Irish Renaissance the vital precursor in technique, craftsmanship, and wit. Vera was taken by Marie Prescott (1853–1923), who played the title role at the Union Square Theatre in New York from 20 August 1883 for a week (to hostile notices) with later touring in upper New York state. Wilde returned to the USA for the production (11 August to 11 September). Meanwhile Mary Anderson commissioned a play from him which he sent her from Paris in March 1883, a historical tragedy in Shakespearian verse, The Duchess of Padua. She rejected it. Her brother Joseph (1863–1943?) later married Gertrude, daughter of the American actor–manager Lawrence Barrett (1838–1891), who staged it in New York from 21 January 1891 as Guido Ferranti, with considerable success cut short by Barrett's death in March.

Wilde lived in Paris from January to May 1883, meeting Hugo, Verlaine, Mallarmé, Edmond de Goncourt, Degas, Zola, Daudet, and his own first major biographer, Robert Harborough Sherard (Kennedy) (1861–1943), a Francophile revolutionary enthusiast whom he saw almost every day, and who brings him vividly to life in these days. Wilde then resumed his lectures, adding ‘Impressions of America’, and performing all over the British Isles. On 25 November 1883 he became engaged to Constance Mary Lloyd (1858–1898), a protestant Dublin girl, whom he had known since 1881. They married at St James's (Church of England) Church, Sussex Gardens, Paddington, London, on 29 May 1884. The honeymoon was spent in Paris, where Sherard had to cut short private confidences on the delights of the wedding night from an ecstatic Wilde. Wilde's sexual experiences to date seem to have been entirely heterosexual. The speed with which he took up homosexual activity after introduction to it some three years later by Robert Ross is evidence in itself against any previous acquaintance with it; he astounded his later lover Lord Alfred Douglas by stating that no such thing existed in Portora. Sherard later recalled Wilde's mention of syphilis at Oxford after experience with a female prostitute. Wilde thought himself cured of this (if it ever happened) although it is possible, as Ellmann speculates, that he later feared it lingered (the enchanted portrait of Dorian Gray seems to reveal syphilis among other physical evidence for the foul life lived by its perfectly preserved original). His marriage was sexually vigorous, with his son Cyril born on 5 June 1885, at the Wildes' new home in London, 16 Tite Street, Chelsea, while his son Vivian (later altered by its owner to Vyvyan) Oscar Beresford [see Holland, Vyvyan Beresford] was born on 3 November 1886. The resultant strain on the Wildes' finances led them to abstain from sexual intercourse. Constance inherited £900 a year from her grandfather John Horatio Lloyd QC, but Wilde's earnings were entirely freelance and involved contributions to his mother's upkeep. Remembering his father's sexual infidelities (resulting in at least three bastards), Wilde recoiled from the thought of sexual solace with other women, and Ross seems to have exploited his sexual hunger and refusal to betray his heterosexual bed. Wilde never seems to have engaged in anal penetration either actively or passively.

The artist as critic, 1885–1891

From early in 1885 Wilde was a regular book critic for the Pall Mall Gazette. Under the pressure of rapid book reviewing Wilde began to make his comic genius serve his aesthetic evangelism in print, as he had been doing on the lecture platform and at the dinner table. Constance Wilde took up her husband's beliefs in dress reform, displayed rational dress to advantage, and spoke fluently on the subject. Wilde's own maturity in prose dates from his marriage. Significantly, his first timeless successes as a writer came in fields also cultivated by his wife: costume, and fairy-stories. His first major essay, ‘Shakespeare and stage costume’ (Nineteenth Century, May 1885) brought his prose comedy into its own. Later revised as ‘The truth of masks’ for inclusion in his essay collection Intentions (1891), it was Wilde's first presentation of his masque of masks whose reader can never be sure how seriously to take the author—and neither, apparently, can the author. It coincided with his best verses before the Ballad: ‘To my Wife with a Copy of my Poems’, a miniature of egocentric tenderness, and ‘The Harlot's House’, which launched the decadence of the 1890s five years early.

‘The Canterville Ghost’ and ‘Lord Arthur Savile's Crime’ (spring 1887) used society comedy as skilfully as Irish folklore, foreshadowing Wilde's return to playwriting. Edmund Wilson in Classics and Commercials (1950) diagnosed ‘a sense of damnation, a foreboding of tragic failure’ (p. 336) even in Wilde's earlier work. Lord Arthur confronts horrors of possible social disgrace and criminal trial when a fortune-teller predicts he will commit a murder; the ghost enjoys haunting American purchasers of his family home by Irvingesque theatrical performances but suffers for his life's crimes in the purgatory from where the Isola-like Virginia finally rescues him. The two stories make excellent use of modern forms, the former originating in the first of Wilde's delicate and deadly dissections of English aristocratic social gatherings, while the latter arises hilariously from Wilde's shrewd witness to British–American social confrontations.

To raise an income Wilde became editor of Cassell's monthly magazine the Lady's World, which he promptly renamed the Woman's World, serving for its issues from November 1887 to October 1889. The Happy Prince and other Tales was published by Alfred Nutt in May 1888: its origin in Irish oral narrative is affirmed by his subsequently reciting the stories to his sons, weeping for ‘The Selfish Giant’ when the child befriended by the giant becomes the crucified Christ who takes his protector to paradise. Their permanent place in child affections refutes the vulgarism that Wilde's literary reputation arose from his legal notoriety. In all cases they are on the child's side, celebrating the courage and generosity of the poor and vulnerable, while their satire mocks the kind of pomposity and hypocrisy children can recognize. January 1889 saw publication of his ‘Pen, pencil, and poison’ (Fortnightly Review), an aesthetic ‘study in green’ of the forger, artist, and poisoner Thomas Griffiths Wainewright and of ‘The decay of lying’ (Nineteenth Century), an elegantly Platonic dialogue supposedly denouncing the renunciation of invention by modern story-tellers while actually dissecting them in a succession of hilarious but profound epigrams. The Wainewright essay startlingly reveals Wilde's criminologist credentials long before his acquisition of practical experience of prison. Forgery also dominated ‘The portrait of Mr W. H.’, whose first draft in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine (July 1889) Wilde expanded to book length. It was not returned by its intended publisher, John Lane, when Wilde's trials put paid to its publication (realized in a limited New York edition in 1921 and a London commercial publication in 1958). A painting is forged to provide evidence for the existence of a boy actor as recipient of Shakespeare's sonnets and creator of his heroines: does the forgery impair the thesis or provide proof of its perpetrator's conviction, all the more when its discovery induces suicide? ‘No man dies for what he knows to be true. Men die for what they want to be true, for what some terror in their hearts tells them is not true’ (O. Wilde, Complete Works, 349). The story is gratifyingly post-modern in its doubts about scholarly certainties: the zealot loses faith having converted his target. It also points out that the place to look for a male lover for Shakespeare must initially be in his own profession, and the sonnets might be expected to have some relevance to the plays.

Wilde relinquished the Woman's World, much enlivened by his literary notes, and left book reviewing after a review-essay (The Speaker, 8 February 1890) on the fourth-century BC Chinese sage Chuang Tz?. He extolled the philosopher who saw perfection in ignoring oneself, divinity in ignoring action, and sagacity in ignoring reputation, silently marking the contrast from himself by thoughts on how disturbing Chuang Tz? would be at dinner parties (at which Wilde himself was now London's leading lion). His valedictory to criticism (Nineteenth Century, July and September 1890) was reprinted in Intentions as ‘The critic as artist’, where he transformed remunerative hackwork into a creative creed. The critic's response to the work of art under review should be to make another. This was set out in a gorgeous profusion of epigram and paradox, ostentation and learning, frivolity and wisdom, but few critics reached deeper into the heart of their business than Wilde's evangel.

In July 1890 Lippincott's Magazine published Wilde's first version of The Picture of Dorian Gray. His critic's interest in Stevenson's Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (‘reads dangerously like an experiment out of the Lancet’: ‘Decay of lying’) induced the idea of age and its spiritual effects expressing themselves in the portrait whose model walks free of either. ‘The decay of lying’ had nature imitating art: in Dorian Gray nature imitates art with—literally—a vengeance, when in knifing the portrait Dorian kills himself and becomes the final horror to which its successive changes have evolved. Dorian Gray himself became a name as immortal as those of Jekyll and Hyde, his picture in the attic baring his self-obsessed soul as vital a symbol as the ‘madwoman in the attic’, the discarded first wife established in Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre (1847). The story itself, so far from vindicating art for art's sake, asks what it profiteth a man to gain the whole world, and suffer the loss of his own soul. His sexual sins, so far as we know them, are firmly heterosexual. He attracts two men, the artist Basil Hallward who has fallen in love with his appearance, and Lord Henry Wotton, whose scruples might be philosophically less nice than Hallward's but who never seems to go beyond repainting Dorian in epigrams. The fervent expression of Hallward's love (arguably the finest sentiment in the story) unleashed the venom of Wilde's Oxford classicist contemporary Samuel Henry Jeyes (1857–1911), who in the St James's Gazette (20 June 1890) demanded that the book be burnt and hinted that its author or publisher were liable to prosecution in terms which suggested more familiarity with homosexuality than his vehemence warranted; comparably, Charles Whibley in the Scots Observer accused Wilde of writing for ‘none but outlawed noblemen and perverted telegraph boys’. Wilde revised it, toning down a few passages for book publication, adding six new chapters to the book and about nineteen years to the action. His preface disposed of his critics in an epigram sequence. Technically the amendments are improvements. Wilde, contrary to what he liked to say, was a very hard worker when it came to revising his writings, and from Vera onwards could be ruthless in what he removed. Despite, or possibly because, W. H. Smith refused to stock it (‘filthy’ was his description), it was the most famous novel of its time. On its appearance in April 1891, the critics were quieter, but still confused, apart from Pater, who reviewed it enthusiastically for The Bookman (November 1891).

Politics and the theatre: the years of mastery, 1891–1895

Wilde moved more fully into social criticism with his ‘The soul of man under socialism’ (Fortnightly Review, February 1891), perhaps the most memorable and certainly the most aesthetic statement of anarchist theory in the English language. In 1891 Wilde was hard at work on a play, and also published Intentions and Lord Arthur Savile's Crime and other Stories. In November came A House of Pomegranates—more ornate fairy-stories than the Happy Prince collection and more directly socialist: the happy prince wanted to use his adornments to relieve suffering but the young king discovers his to be the cause of it. The general effect is more tragic, the infanta's dwarf dying of grief when he realizes she likes him only as an object of ridicule for his ugliness, the fisherman and his soul corrupted in their separation, the star-child's expiation for his snobbery and cruelty ending in his life as ruler cut short and his successor ruling evilly. The elegiac, doom-laden note accords with the new spirit of fin de siècle which a character in Dorian Gray had equated with fin du globe.

Lady Windermere's Fan opened under George Alexander's direction and lead male performance at the St James's Theatre, London, on 20 February 1892. It anticipates Ibsen's A Doll's House twenty years after. Ibsen was the crucial influence that turned Wilde from a melodramatist into a dramatist: Wilde was as much his pupil as was Shaw, with whom he linked himself as playwright. Mrs Erlynne, like Ibsen's Nora, has left her husband and offspring and returns to blackmail Lord Windermere, her son-in-law, on the threat of self-disclosure to her daughter who believes her to have died a loving wife. Lady Windermere, led by suspicion that her husband's payments to Mrs Erlynne are recompense to his mistress, leaves her home to elope with Lord Darlington, from which decision Mrs Erlynne rescues her at further cost to her own reputation. Mrs Erlynne is a figure of potential tragedy, but she is also much the wittiest person in the play and ultimately deals herself a happy ending with an infectious cynicism. She endangers her own future to save her daughter from the brittle, loveless life into which her bid for freedom had enmeshed her. The play was revolutionary in its mingling of the vocabulary of comedy, the potential of tragedy, and the insistence on realism.

Herbert Beerbohm Tree was actor–manager for Wilde's next play, A Woman of No Importance, after Lady Windermere's Fan had run to delighted audiences and enraged critics (save for the Ibsenite William Archer) in London and on tour through almost all of 1892. The title role for Tree's production described an unmarried mother doing exactly what Mrs Erlynne denied modern life would permit: to become a dowdy, having been victimized by a dandy. Mrs Bernard Beere played Mrs Arbuthnot while Tree played Lord Illingworth, the treacherous dandy, who encounters his former mistress and their son twenty years after, while he is conducting a flirtation with Mrs Allonby (played by Mrs Tree), who recalls Mrs Erlynne's conversation without her complication. Tree had more in common with Wilde than any other actor and thus may have been more alive to the dangers of his more liberated epigrams, some of which were deleted, notably when Tree sidetracked a seventeen-year-old blackmailer named Alfred Wood, for which Wilde gratefully gave Mrs Allonby the entrance line ‘The trees are wonderful, Lady Hunstanton. But I think that is rather the drawback of the country. In the country there are so many trees one can't see the temptations’, that is, one could not see the Wood for the Trees. Only the first four words remained in the text, which may be all Wilde intended to happen: uttered by Mrs Tree, they must have raised a fine laugh from the regular customers at the Haymarket Theatre, where the play opened on 19 April 1893, running until 16 August. For all of Wilde's cult of the dandy, Illingworth is defeated and discredited at the play's end, at the hands of the somewhat absurd American puritan girl who makes a man of Illingworth's bastard.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Brighton, 1872 - 1898, Menton, France

Worcester, 1870 - 1945, Lancing