Walter Pater

London, 1839 - 1894, Oxford

LC name authority rec n.n79117248

LC Heading: Pater, Walter, 1839-1894

Biography:

Pater, Walter Horatio (1839–1894), author and aesthete, was born on 4 August 1839 at 1 Honduras Terrace, Commercial Road, Stepney, London, the third of the four children of Richard Glode Pater (1797?–1842), surgeon, and Maria Hill (bap. 1803, d. 1854). Ancestors of the Paters had come to England from the Netherlands in the seventeenth century and settled in Buckinghamshire. Pater's siblings comprised the eldest, William (1835–1887), who qualified as a surgeon and ultimately directed the Staffordshire county hospital for the mentally ill; Hester (Totty; 1837–1922) , an accomplished embroiderer and friend of Mrs Humphry Ward and Virginia Woolf; and Clara Ann Pater (bap. 1841, d. 1910), a founder and tutor of Somerville College, Oxford. The children's father died in 1842 when Walter was two, and the remaining extended family, including his widow, the four children, a paternal grandmother, and an aunt, left Stepney later that year for Grove Street near Victoria Park. This move to a more salubrious setting in suburban South Hackney brought them into the parish of the Revd Henry Handley Norris, influential leader of the high Anglican Hackney Phalanx. By 1847 the family had moved even further north of the conurbation, to rural Enfield in Middlesex. In both Hackney and Enfield the children were tutored privately at home until, from 1851, the boys peeled away: by that year William was at work, and in 1852–3, at twelve, Walter attended Enfield grammar school for a year, where he was known as Parson Pater.

Youth and friendships

By early 1853 the family had moved to Harbledown, Kent, a county in which Pater's cousins resided, in order for Walter to attend the King's School, Canterbury, as a day boy. A year later, in February 1854, his mother died. Orphaned at fourteen and forced to confront the reality of death, he may have been particularly open to two aspects of his school life: the relationship between the King's School and the great cathedral at Canterbury on whose precincts the school buildings border, and the forging of close male friendships. If the cathedral reinforced the young man's imaginative involvement with religious experience in its widest sense, his close friendships with Henry Dombrain (from 1854) and John Rainier McQueen (from 1855), with whom he made up ‘the triumvirate’, established a pattern of shared studies, country rambles, and an enthusiasm for church services which is echoed in subsequent friendships with, for example, his student and colleague C. L. Shadwell at the beginning of his career and F. W. Bussell, the chaplain of Brasenose College, at its end. Certainly, diverse forms of Christianity and other systems of belief were to retain importance to him through periods of commitment to religion, repudiation of it, and ambivalence.

While at school Pater read works by contemporaries such as Tennyson, Ruskin (Modern Painters), and Dickens (Little Dorrit), and wrote poetry of his own, some of which juvenilia is preserved in archives and biographies. According to McQueen (Wright, Life and Autobiography) Pater suffered a difficult period of religious doubt in 1857–8 and broke up the triumvirate as he prepared to leave for university. Having matriculated at Queen's College, Oxford, in June 1858, he left the King's School in August with prizes for Latin and ecclesiastical history, and an exhibition supplemented by an additional sum, probably from the McQueens. The tenuous income of the Pater family is also signalled at this moment of financial pressure by the abandonment of the Harbledown house and the departure of Hester, Clara, and their aunt for Heidelberg, where the girls could live cheaply chaperoned by their aunt, learn German with a view to teach, and perhaps take pupils in English.

At Queen's, Pater read classics; his tutor was W. W. Capes, a young non-clerical fellow whose special interest was ancient history and whose lectures stimulated students to read widely and so critically that when he took orders in 1862, many were surprised. In the wake of the Oxford Movement, Matthew Arnold's displacement of religion by culture, and the claims of science, debates within and about Anglicanism permeated all aspects of university culture in the late 1850s: by 1860, when Benjamin Jowett, a fellow of Balliol College and one of the ‘seven against Christ’ who contributed to Essays and Reviews (1860), offered to tutor Pater and his close friend Ingram Bywater, their association with Jowett located them among the renegades.

During the summer and autumn of 1860 McQueen angrily ended his friendship with Pater, for reasons he was never prepared to clarify, but his denunciation of Pater's apostasy to the bishop of London in 1862—when Pater was considering ordination—suggests that Pater's contact with Jowett did indeed signify an alliance with scepticism and the ‘higher criticism’ of the Bible as practised by German critics. Further understanding of the unspeakable reasons for McQueen's break with Pater may lie in Bywater's claim that, contrary to Edmund Gosse's account in the 1895 volume of the Dictionary of National Biography, in these early Oxford years Pater and Bywater shared ‘a certain sympathy with a certain aspect of Greek life’ (Jackson, 79). Pater's earliest published review essays, ‘Coleridge's writings’ (1866) and ‘Winckelmann’ (1867), respectively articulate these two alleged positions, on religion and sexual orientation, as do two unpublished essays of 1864, ‘Diaphaneite’, and the lost ‘Subjective immortality’ on Fichte written for the university essay society, Old Mortality, to which Pater and Bywater were elected in that year. So theologically objectionable was the Fichte essay in its denial of a Christian afterlife, that on hearing of it Canon Liddon, an active defender of the high-church party at Oxford, and Gerard Manley Hopkins, then an undergraduate, started a rival, Christian, society, the Hexameron. In 1864 too, Pater burnt his poetry, much of which had been religious, signalling his break with Christianity at this time.

Fellow of Brasenose

In December 1862, disappointed with his (second-class) degree results in literae humaniores, Pater left Queen's; he moved to rooms in the High Street, Oxford, and began coaching, and attempted first to gain a curacy and then, stymied by McQueen's opposition, to seek fellowships, the first two unsuccessfully, perhaps because they were clerical. In February 1864 he was elected as a probationer to the first non-clerical fellowship at Brasenose College in classics; he tutored from the outset, and opted to lecture from 1867. Having installed his sisters in London just after he took his degree (his aunt, their chaperone, had died in Dresden), he was free in 1865 to vacate his High Street rooms for the unattached, male community at Brasenose, where he resided between 1865 and 1869. Among his tutorial students was Gerard Manley Hopkins; among his close friends in Oxford, Mary Arnold, Ingram Bywater, Mark and Emilia Pattison, C. L. Shadwell, T. H. Ward, and T. H. Warren; at Eton was Oscar Browning.

It was during this period of bachelor existence as a young fellow that Pater wrote three outspoken but anonymous review essays for the Westminster Review which were to set the tone, in their various assaults on orthodoxy, for his subsequent reputation and work. In the first, ‘Coleridge's writings’, he decries theological and philosophical absolutism; in ‘Winckelmann’ he explores a more corporeal aesthetic, unmistakably portraying Winckelmann's advocacy of the Hellenic and the homoerotic; in ‘The poetry of William Morris’ (1868), a substantial critique which makes explicit the links between Pater and his Pre-Raphaelite contemporaries, Pater is among the early advocates and definers of ‘aesthetic poetry’. Culminating in a conclusion which reflects Morris's Pre-Raphaelite poetry of the 1850s and 1860s, the review recommends the cultivation of a life of ‘highest’ moments, free from dogma, to which aim—‘to burn always with this hard, gem-like flame’—art and poetry lead most directly but not exclusively: allowance is made ‘for the face of one's friend’, continuing the homosexual motif of ‘Winckelmann’. These earliest published pieces, written for the ‘wicked Westminster’, continued to attract controversy throughout Pater's career, and the ‘Conclusion’ from the Morris essay, denounced from pulpits and adopted by aesthetes, was to remain the keynote of Pater's reputation as a ‘Protestant Verlaine’ (Moore, 529) even while it swelled to include art history, the novel, the short story, classical philosophy, and archaeology.

In 1869 Pater and his sisters took a house at 2 Bradmore Road in north Oxford, joining a community which had as its typical resident a new kind of Oxford academic, the married fellow, whose existence gradually leavened the male, homosocial, and clerical community of the university which Pater and his contemporaries had entered. At Bradmore Road, Pater's social life expanded through entertaining and living with his sisters, the younger of whom, Clara, learned Latin with other female neighbours and helped to organize the Association for Promoting the Education of Women and to create Somerville College. From 1869 Pater began to dress like a dandy, wearing a top hat, apple-green tie, and pigskin gloves, and in that year he began a signed series of four articles in the Fortnightly Review on Renaissance subjects. The first, on Leonardo da Vinci (1869), included the now famous invocation of the Mona Lisa which begins ‘She is as old as the rocks upon which she sits’, the influence of which Yeats articulated and perpetuated late into the twentieth century when he printed this passage as the first poem in his Oxford Book of English Verse (1939). This first Fortnightly article of 1869 was the début of the association between Pater's name and literary style, for which his work came to be well known. Pieces on Botticelli, Pico della Mirandola, and Michelangelo followed, and in 1872 he collected these and ‘Winckelmann’, combined them with new essays produced expressly for his book, including a ‘Preface’ which drew on existing material (from ‘Diaphaneite’ and ‘Coleridge's writings’), and appended the ‘Conclusion’ from the Morris essay, to form Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873). This process of cultural production—accreting work over time and reproducing, reordering, and cutting and pasting it to form a shaped sequence—was to characterize, in various permutations, all of his subsequent books except Marius the Epicurean, which alone did not benefit from the system of pre-book serialization. However, truncated from its origins in the Westminster Review, the anonymous addendum to the review of Morris's work, recirculated and relocated as the famous ‘Conclusion’ to the signed volume of 1873, proved troublesome in its new context, being withdrawn in 1877 and reinstated in 1888. The same controversy attached to the body of the Morris review when, after twenty years, it was reintroduced in 1889 in Appreciations as ‘Aesthetic poetry’, only to be removed from the second edition of 1890.

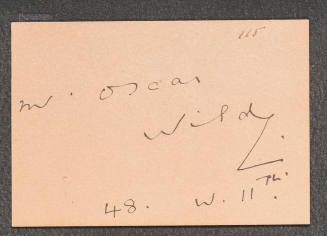

In Studies Pater drew on current scholarship, extending the period and location of the Renaissance from sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Italy to fifteenth-century provincial France and eighteenth-century Germany, and the term ‘Renaissance’ from its historical manifestation in specific periods and locations to an idea which is transhistorical. He was to do likewise with the terms Romantic and classical in 1876 in his essay on Romanticism. Moreover, the ‘Preface’ of Studies directly addressed Matthew Arnold, deftly turning his emphasis on the quiddity of the object ‘as it really is’ to the subjective: ‘What does it mean to me?’ The volume was also notable for its admixture of genres—history, criticism, biography, portraiture—and its adherence to gendered discourse, in which homosocial histories and aesthetics were pursued and delineated. Studies attracted attention, in the press where its claim as ‘history’ was denied, in the pulpits of the university where the hedonism of the ‘Conclusion’ was rejected and its danger for students proclaimed by W. W. Capes and others, and at Brasenose where John Wordsworth, a colleague, objected privately by letter. Oscar Wilde's repeated designation of Studies as his ‘golden book’ from the late 1870s promulgated its notoriety to a wider public and for a longer period than it might otherwise have penetrated. It was twelve years before Pater dared to publish his next book.

A leading aesthete

Through Studies, Pater was now publicly linked by reputation with the aesthetic school and the unorthodox sexualities associated with it through the work and lives of A. C. Swinburne and D. G. Rossetti. For those in a position to know, this was confirmed by knowledge of Pater's intimacy with the painter Simeon Solomon and Swinburne between the late 1860s and February 1873, the month in which Studies appeared, and Solomon was charged with gross indecency and imprisoned. A year later it was Pater's turn: in February 1874 letters signed ‘yours lovingly’, from Pater to a Balliol undergraduate, William Money Hardinge, were passed to the master of Balliol and resulted in the temporary suspension of Hardinge and a threat of exposure for Pater; interviewed by Jowett, Pater was warned to avoid application for any university post, and soon after he was passed over for the post of university proctor. Without much independent income, and helping to support both his sisters at that time, he was economically vulnerable; he needed to retain the salary attached to his fellowship, tutoring, and lecturing.

The danger of expulsion was real enough, as the ousting of J. A. Symonds from Oxford (1862) and Oscar Browning from Eton (1875) exemplified. Public and often homophobic hostility to aestheticism in the press, such as the Revd R. Tyrwhitt's article ‘The Greek spirit in modern literature’ (1877), and the verdict in the Ruskin v. Whistler libel case (1878), articulated and influenced public morality. If the portrayal of Pater as the aesthete Mr Rose in W. H. Mallock's satire The New Republic (June–December 1876) was more playful and benign, it nevertheless served to circulate Pater's reputation for hedonism, and to feed suspicion of his moral and sexual orthodoxy. The combination of this external pressure and his vulnerability at the university moved him to suppress the ‘Conclusion’ in the second edition of Studies (published as The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry) in 1877, and in 1878 contributed in part to his decision not to publish a second book, Dionysus and other Studies, though type was set and the volume advertised. He also withdrew his applications for two university posts vacated by Sir Francis Doyle and John Ruskin respectively, the professorship of poetry in 1877 and the Slade professorship of fine art in 1885.

However, in parallel with these strategic acts of self-censorship after Studies, Pater continued to publish signed articles at regular intervals in the Fortnightly Review and Macmillan's Magazine, first on English literature, then more boldly, again, on Renaissance art (‘Giorgione’). In 1876 he lectured and published three articles on ancient Greek texts and myths (Demeter and Persephone, and Dionysus) which permitted him to reiterate and explore moments of ‘high passion’, sexuality, and violence. In 1879, following the cancellation of his book, he published nothing, but in 1880 three more Greek studies appeared, and an essay on Coleridge, the first of two he was to contribute to T. H. Ward's Macmillan anthology The English Poets, the second being on D. G. Rossetti (1883). Besides bringing together his teaching (of classics) and his writing in this period, he developed the portrait/biographies of Studies into a hybrid genre of fiction and history which he called the ‘imaginary portrait’. In 1878 the first, an autobiographical short story called ‘The Child in the House’, appeared in Macmillan's Magazine, and with the aim of writing a novel, he published very little between 1881 and 1884; in 1882 he travelled to Rome to research it, and in 1883 resigned his tutorship.

Marius the Epicurean, Pater's only finished novel, appeared in March 1885 in two volumes. Set in a period of transition between decadent classicism and new Christianity, in the Rome of Marcus Aurelius, Marius deals with questions of morality, Christianity, and gender in a structure which resolutely extends the boundaries of fiction to history and criticism, in a style which is elaborately literary. In the third edition of The Renaissance in 1888, Pater restored the ‘Conclusion’ excluded from the 1877 edition and, in a note of explanation, linked the critique it provoked with Marius; situating that novel as a response to the ‘Conclusion’, he claims that Marius dealt ‘more fully ... with the thoughts suggested by it’. An extended imaginary portrait, Marius the Epicurean reproduces too the gendered discourse of Studies, echoing its succession of male protagonists and pairs, and barely acknowledging the heterosexual exigencies of English fiction in this respect.

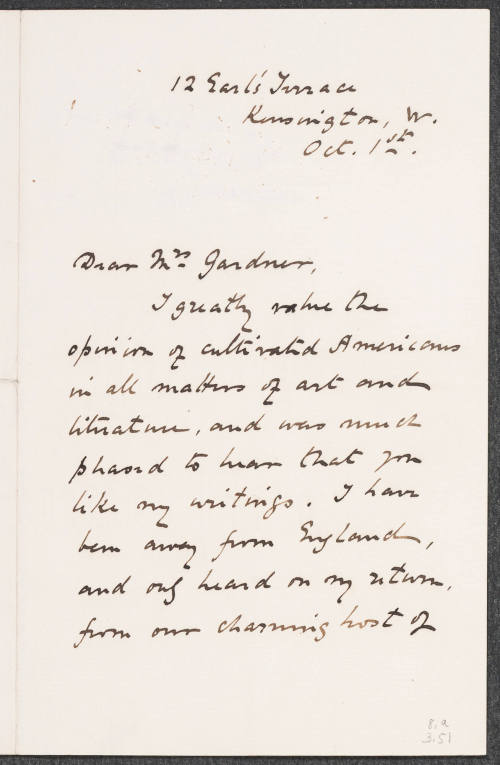

Marius seemed to liberate Pater at last from the shadow of controversy, a liberation which may have been enhanced by the transfer of the household from Oxford to 12 Earl's Terrace, Kensington, London, soon after Marius appeared, in August 1885. Under the new arrangement Clara and Walter spent term-time in their respective college rooms in Oxford, and vacations and occasional weekends in the London house which Hester ran. A contemporary impression of the effect on Pater may be judged by perusing a pair of drawings by Charles Holmes, one of Pater unkempt in Oxford and the other of the dapper man of town in London. But it was probably liberating for Pater at both ends, from his sisters and domestic life in Oxford and from his colleagues in London.

Later works

The second half of the 1880s proved one of Pater's most prolific periods; he published two books which rapidly went into second editions, a number of articles and reviews, and an unfinished serialized novel. Imaginary Portraits (1887) consisted of four short stories about four young men defined historically and geographically, but distant from the present and each other; all die young. ‘A Prince of Court Painters’ takes as its subject a student of Watteau, the Flemish painter Jean Baptiste Pater, whom the author regarded as his ancestor. ‘Gaston de Latour’, six chapters of which appeared between June 1888 and August 1889, similarly blends history and fiction and conforms to the pattern of the imaginary portrait; Pater described it in an undated letter as ‘a sort of Marius in France, in the 16th Century’ (Letters, 126).

Appreciations: with an Essay on ‘Style’ (1889) is Pater's only volume of literary criticism and his sole treatment of English literature, though contemporary reviewers noted the French origins of its title and its title-essay which is based on an earlier anonymous review of Flaubert. ‘Greek as Mr. Pater is in soul, his models of style are all French’, noted Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine (Oliphant, 144). Pater dug deep to construct this eclectic book, which included articles originating in the 1860s, 1870s, and 1880s. Two theoretical pieces, ‘Style’ and ‘Postscript’, which frame the collection take issue with Matthew Arnold, ‘Style’ promulgating ‘imaginative prose’ rather than poetry as ‘the special art of the modern world’, and ‘Postscript’ Romanticism over the classical. Although Appreciations devotes no single essay to the English novel, its foregrounding in ‘Style’ of formal stylistic elements as the basis of good literature and the quality of the matter as the mark of great literature may be read as a tacit support of contemporary efforts by George Moore and others to free the novel from censorship. As a literary critic Pater wrote sparingly on contemporary or even modern writing; dividing his attention between French and English, he favoured English poetry and French prose, though he did review English prose by friends, such as Wilde's Dorian Gray, Mary (Mrs Humphry) Ward's Robert Elsmere, and Vernon Lee's Juvenilia. Close friends of the 1870s and 1880s, from Oxford and London, included Charlotte Symonds Green, Edmund Gosse, George Moore, Violet Paget (Vernon Lee), Mark-André Raffalovich, William Sharp, Arthur Symons, Mary Robinson, and Oscar Wilde, all of whom are characterized, notably, by their association with the violation in some respect of sexual conventions of the period.

In 1893 Pater published Plato and Platonism, which related closely to his teaching. Evolving characteristically serially, sections of it developed from lectures to chapters, and parts were serialized as magazine articles. Jowett, translator and popularizer of Plato, approved, and the two men made their peace almost twenty years after their confrontation in 1874. Pater's other work of the 1890s reflects the assimilation of French culture into English decadence of the period. Whereas after Studies Pater expunged references to Baudelaire from his published work, he now wrote preponderantly on French culture—on Prosper Mérimée and Pascal, and on churches at Amiens and Vézelay. He published too a last imaginary portrait, ‘Emerald Uthwart’ (1892), which, unusually, like ‘A Child in the House’, is set in England, invites reading as autobiography, and invokes in its title his youthful metaphor of the ‘gem-like flame’.

There is no agreement among critics about Pater's degree of faith, if any, in the 1890s. Contemporary sources are almost all blighted by bias. His most intimate companion at Brasenose from 1891 was its dandified, multifaceted, and youthful chaplain, F. W. Bussell, with whom Pater used to dine, walk, attend chapel and diverse church services, and visit in the country and in London. It was Bussell with whom Pater chose to be paired in Will Rothenstein's lithographs of Oxford Characters (1895), and Bussell whose ‘character’ Pater contributed to that work. Bussell, in his memorial sermon, and Edmund Gosse in the Dictionary of National Biography attest to Pater's intensification of faith in his later life, whereas the first act of tribute by C. L. Shadwell, fellow of Oriel and Pater's literary executor and old friend, was to collect and publish a posthumous volume of Greek Studies. In a remarkable and frank testament to his friendship with Pater which Gosse published in the Contemporary Review in December 1894, and from which he extracted his more decorous Dictionary of National Biography life, Gosse, echoing Pater in ‘Botticelli’, surmised the following: ‘He was not all for Apollo, nor all for Christ, but each deity swayed in him, and neither had that perfect homage that brings peace behind it’ (Gosse, 810).

Between 1873 and 1894 Macmillan published five Pater titles, four in more than one edition, and three new titles appeared posthumously soon after his death. Contributing to a wide range of Victorian serials, from popular daily papers to high-culture quarterlies, topical monthlies, and weeklies, Pater steadily circulated his distilled prose and considered views on questions of his day. Henry James characterized Pater's alleged inscrutability as ‘the mask without the face’ (Selected Letters, 120), but, writing in the comparative safety of the period before the trials of Oscar Wilde and in the space ‘classics’ permitted, Pater's politics, and inscriptions of homosexual and homosocial histories, art, and culture, are pervasive, there for the reading, in journals as diverse as the Westminster Review and Harper's. Repeatedly invoked by younger decadents of the 1890s such as Yeats, Symons, Herbert Horne, Gleeson White, Le Gallienne, and Lionel Johnson, and honoured by discerning men and fewer women of his own generation, Pater was seldom accorded more general recognition in his lifetime; an honorary LLD from the University of Glasgow in April 1894 proved a singular exception. It remained for biographers, critics, historians, and novelists in the twentieth century to piece together the elusive traces of his life, much of which had been withheld or destroyed by his family and friends, and to claim him variously as an important early modernist, and writer of gay discourse. In July 1893 the Paters left London to return to Oxford, possibly owing to Pater's gout, and on 30 July 1894, at his home at 64 St Giles', he died suddenly of a heart attack at the age of fifty-four. He was buried at Holywell cemetery, Oxford, on 2 August.

Laurel Brake

Sources T. Wright, The life of Walter Pater, 2 vols. (1907) · T. Wright, Thomas Wright of Olney: an autobiography (1936) · M. Levey, The case of Walter Pater (1978) · S. Wright, Walter Pater: a bibliography (1975) · E. Gosse, Contemporary Review, 66 (1894), 795–810 · DNB · B. A. Inman, ‘Estrangement and connection: Walter Pater, Benjamin Jowett and William Money Hardinge’, Pater in the 1990s, ed. L. Brake and I. Small (1991) · The letters of Walter Pater, ed. L. Evans (1970) · L. Brake, Subjugated knowledges (1994) · L. Brake, Walter Pater (1994) · T. Hinchcliffe, North Oxford (1992) · W. W. Jackson, Ingram Bywater (1917) · G. Moore, ‘Avowals. vi: Walter Pater’, Pall Mall Magazine, 33 (1904), 527–33 · Selected letters, ed. R. Moore (1988) · [M. Oliphant], ‘The old saloon’, Blackwood, 147 (1890), 131–51 · L. Dowling, Hellenism and homosexuality in Victorian Oxford (1994) · I. Fletcher, Walter Pater (1959) · R. M. Seiler, Walter Pater: a life remembered (1987) · IGI · grave, Holywell cemetery, Oxford, Oxfordshire · tithe book for South Hackney, 1843, Hackney Local History Library · Kelly's Post Office London directory (1845–6) · Post Office directory of London and nine counties [1846]

Archives All Souls Oxf., letters and unpublished chapters of Gaston de Latour · Bodl. Oxf., autobiographical notes, corresp., and MSS · Brasenose College, Oxford, corresp. and MSS · Colby College, Waterville, Maine, papers · Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, papers · Harvard U., Houghton L., corresp. and papers :: BL, letters to E. Gosse, Ashley 5739 & A. 3733 · BL, corresp. with Macmillans, Add. MS 55030 · Colby College, Waterville, Maine, Vernon Lee MSS, letters · King's Cam., letters to Oscar Browning · King's School, Canterbury, Hugh Walpole collection · Morgan L., Gordon Ray bequest · NYPL, Berg collection, letters to Violet Paget (also known as Vernon Lee) and chapters of Gaston de Latour · U. Leeds, Brotherton L., letters to E. Gosse · University of Indiana, Bloomington, Lilly Library, Thomas Wright MSS, letters

Likenesses W. S. Wright, oils, 1870–1879?, repro. in Wright, Life of Walter Pater, 246 · S. Solomon, drawing, 1872, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy · photograph, 1880–1889?, repro. in E. Gosse, History of English literature (1903) · C. Holmes, sketch, 1887, repro. in Self and partners (1936), following p. 102 · Elliott & Fry, photograph, 1889, Brasenose College, Oxford · C. Holmes, sketch, 1890–91, repro. in Self and partners (1936), following p. 102 · Elliott & Fry, photograph, 1890–94, NPG [see illus.] · Spider [J. Hearn], cartoon, Indian ink, 1890–94, repro. in T. Wright, Autobiography (1936), 212 · W. Rothenstein, drawing?, 1894, BM; repro. in Oxford characters (1896) · marble bust relief, memorial plaque, 1895, Brasenose College, Oxford · A. A. McEvoy, oils, 1906 (after sketches and photographs), Brasenose College, Oxford · R. Lasley, print, 1991, repro. in Brake and Small, eds., Pater in the 1990s · caricature, Queen's College, Oxford · group portrait, photograph, King's School, Canterbury · photogravure, BM; repro. in W. Pater, Greek studies (1895)

Wealth at death £2599 4s. 3d.: administration, 19 Sept 1894, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–15

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Laurel Brake, ‘Pater, Walter Horatio (1839–1894)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2006 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/21525, accessed 29 Oct 2015]

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Château Saint-Leonard, France, 1856 - 1935, Florence

Northamptonshire, 1851 - 1924, Oxford

Saxmundham, England, 1843 - 1926, Sissinghurst, England

Crowthorne, 1862 - 1925, Cambridge, England

Paisley, Scotland, 1855 - 1905, Syracuse, Sicily