Violet Paget

Château Saint-Leonard, France, 1856 - 1935, Florence

(b Château Saint-Leonard, nr Boulogne, 14 Oct 1856; d Villa Il Palmerino, nr Florence, 13 Feb 1935).

English writer and art historian. Born of English parents, she was privately educated in Europe and was the childhood friend of John Singer Sargent. Her first published art-historical work, Belcaro (London, 1881), propounds the aesthetic primacy of form as combining intellectual conception and the physical embodiment of beauty, but with consideration also given to the demands of the materials employed. Viewing the artist as only part of the man, she opposed with great clarity Ruskin’s equation of art with morality, holding that though art has no moral meaning, it has a moral value—the creation of happiness. In Euphorion (London, 1884), however, the partisan nature of her criticism obscures the scholarly insights of her essays on Renaissance art. The enthusiastic reception it nevertheless received was overturned with the publication of her novel, Miss Brown (Edinburgh, 1884), a savage and clumsy satire on the Pre-Raphaelites, whom she had met on her first visit to England in 1881 and among whom it caused much hostility.

Juvenilia (London, 1887), although often rambling, advocates the absorption of art into everyday life. The theme is developed in Althea (London, 1894), Renaissance Fancies and Studies (London, 1895) and Laurus Nobilis (London, 1909); in the second of these Lee also demonstrates a continuing awareness of the artist’s relation to the materials and attitudes of his or her age. Her most controversial publications were two articles written with Clementine Anstruther-Thomson on ‘Beauty and Ugliness’ (Contemporary Review, lxxii, 1897; reprinted with other essays, London, 1912). They proposed a theory of psychological and physiological aesthetics, which suggested that there could be objective physical responses to aesthetic phenomena. The articles attracted some critical attention, especially in Germany, but elicited the (unfounded) charge of plagiarism from an erstwhile friend Bernard Berenson; Lee claimed that at the time neither of them was aware of Theodor Lipps’s related theory of Einfühlung (empathy).

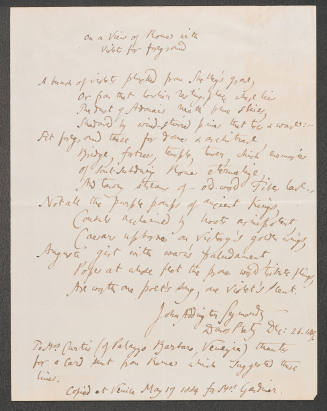

Lee’s final work on aesthetics in art, The Beautiful (Cambridge, 1913), summarizes, cogently and concisely, her earlier views that it is ‘shape’ (form) that determines an appreciation of art, contemplated with ‘attention’, ‘memory’ and an ‘empathetic movement’. Of her essays on gardening, the most measured and authoritative are in Limbo (London, 1897), where she outlines the history of the Italian garden and garden sculpture, contrasting the modern flower garden with the architectural garden of the 16th and 17th centuries. In Hortus Vitae (London, 1904) the concept of the garden was used for impressionistic and unhistorical musings, much along the lines of Genius Loci (London, 1899), travel writings that received, to her chagrin, greater acclaim than her more scholarly texts. Among her later publications are contributions to Anstruther-Thomson’s Art and Man (London, 1924) and to a memorial of Sargent. (Oxforn Art Online, accessed 08/23/2016)

Paget, Violet [pseud. Vernon Lee] (1856–1935), art historian and writer, was born on 14 October 1856 at Château St Léonard, near Boulogne, France. Her mother, Matilda (1815–1896), was the daughter of Edward Hamlin Adams (1777–1842), who came from a wealthy planter's family in Kingston, Jamaica, but made his own fortune from a variety of West Indies business ventures, some of a questionable nature, and eventually purchased Middleton Hall, Carmarthenshire. Despite his strongly voiced opinions against conventional religion and education, he became a member for the county in the reform parliament of 1832. On his death, his sons carried on only their father's contentiousness, not his ability in business, with one brother challenging the legitimacy of the other's children; the resulting litigation blocked all of Edward's children from their inheritance for several years.

Vernon Lee's father, Henry Ferguson Paget (1820–1894), was reputedly the son of a French émigré nobleman who, after settling his family in Warsaw, founded a college for the nobility. Henry, after attending his father's college, undertook various soldiering missions until his involvement in the Warsaw uprising of 1848 forced him to flee to Paris. Meanwhile, Matilda Adams, facing limited financial resources on the death of her first husband, a Captain Lee-Hamilton, also moved to Paris in 1852 with her son from that marriage, Eugene Lee-Hamilton (1845–1907). At that time, Henry Paget was engaged as Eugene's tutor, a position he held until 1855, when he and Matilda were married. Vernon Lee was the much beloved only child of their marriage.

Intellectual development

The Paget household moved at least twice yearly from one place on the continent to another, through France, Germany, Switzerland, and Italy, with the result that Vernon Lee gained fluency in four languages as well as an instinctive internationalist perspective. While she was still very young, both her mother and her half-brother, Eugene, determined that she was to be another Madame de Staël, so that Vernon Lee was raised ‘in an atmosphere of fantastic prodigy-worship’, as Ethel Smyth later described it (Smyth, 51). In a portrait of her mother in The Handling of Words Vernon Lee commented that her mother had taught her to write with ‘common sense and good manners’ (The Handling of Words, 1923, repr. 1968, 297). While Eugene was studying at Oxford and later serving at a Foreign Office post in Paris, his letters to his mother and sister make clear his preoccupation with ‘Baby's intellectual development’. In return, Vernon Lee would dutifully send him essay-like letters in her most careful French, which he would then correct. As a writer, Vernon Lee would pay tribute to Eugene's role in her education when she took on part of his surname as hers in her pseudonym. She also acknowledged his influence in her writings in her dedication to him of Baldwin: being Dialogues on Views and Aspirations (1886). From 1875 until 1894 an almost complete paralysis confined Eugene to an invalid's existence at home, but Vernon Lee became her half-brother's representative to the London literary establishment and sought to interest publishers in his poetry.

Another important influence on Vernon Lee's intellectual development was her childhood friend the American painter John Singer Sargent, whom she first met in Nice when they were ten. During the winter of 1868–9, when they were with their families in Rome, their shared interests, especially in music, and their similar precocity led them to spend so much time together that when John later wrote to Vernon Lee, he described himself as her twin. At this time too, the young friends determined that in their future lives he was to be a painter, she a writer. John's mother, Mary Newbold Sargent, was also an early muse for the young writer. It was during her frequent excursions with the Sargent family in Rome that Vernon Lee acquired from Mrs Sargent what was to be a lifelong appreciation of antiquities and of the true spirit of place. In 1881, on meeting Vernon Lee after a separation of many years, John Singer Sargent painted the portrait of his childhood friend now in the Tate collection. It was clear from the result that he had not forgotten his knowledge of her. Vernon Lee would write to her mother that everyone thought the portrait characteristic of her, and she agreed with them, describing herself in it as appropriately ‘fierce and cantankerous’ (Vernon Lee's Letters, 65).

Early literary career

As her literary mentor during the earliest stages of her career and as her guide to the London literary establishment, Vernon Lee was to choose Camilla Jenkin, a successful popular novelist and family friend. Vernon Lee's letters to her from 1871 to 1878 are a detailed record of the emotional and intellectual development of a gifted young woman of letters. In one of the most memorable of these, dated 28 June 1871, the fifteen-year-old Vernon Lee describes her visit to Rome's Bosco Parrasio on the Janiculum, the site of the long-forgotten eighteenth-century Arcadian Academy and the meeting-place of the leading Italian men of letters. Together with her special attachment to the music of this period, this visit was to confirm eighteenth-century Italy as the focus of her scholarship. She tells Mrs Jenkin how, having recently read Metastasio's works and now having recognized his portrait as a member of the Arcadian Academy, she has decided on her first major literary project:

I now think that Metastasio having lived from one end of his century to the other, having known all the celebrated writers of the 18th century, amongst whom indeed he is perhaps the most admirable and at the same time the most vilified by the modern Italian school, he might with propriety be taken as a specimen of Italian thought of that period, and his life, his friends, his works and his times form an interesting work. (Vernon Lee's Letters, 26)

In addition, she writes, the current custodian of the academy, impressed by Vernon Lee's knowledge, has offered to lend her all the volumes from the archives that she might require for her work. This letter to Mrs Jenkin records a highlight of Vernon Lee's research into the culture of the Italian eighteenth century, begun at the age of thirteen, when, as she described it, she had done so still under the inspiration of ‘an unconscious play instinct’, but it was Mrs Jenkin who would give Vernon Lee the practical guidance she needed to transform into the pioneering scholarship of her first book, Studies of the Eighteenth Century in Italy (1880), her ‘lumber room full of discarded mysteries and of lurking ghosts’ (Studies, 2nd edn, 1907, xvi). Published when she was twenty-four, it was the culmination of ten years of arduous study, much of it of manuscripts of original materials. Often cited as responsible for reviving interest in eighteenth-century Italian drama and music, Studies of the Eighteenth Century in Italy in addition pays special attention in individual chapters to the comedy of masks, the work of Goldoni, and ‘Carlo Gozzi and the Venetian fairy comedy’. It was greeted with critical and scholarly acclaim and was to remain a classic reference work for scholars until the early 1960s. Above all, it demonstrates the young Vernon Lee beginning to carve out a unique domain for herself as a woman writer, as she defines herself as ‘neither a literary historian nor a musical critic, but an aesthetician’ whose role encompasses both fields (Studies, 1880, 1).

In 1881, on the first of her almost annual visits to England from her family's new permanent residence in Florence, Vernon Lee found that her literary success brought her numerous invitations to the most notable literary and artistic circles of the time. Robert Browning and Walter Pater, it was said, were among her admirers. She soon became known for her tailored dress, with high Gladstone collar and starched shirtfront, her clever conversation, and her piercingly intelligent eyes behind her spectacles. From this first visit until 1894 Vernon Lee recorded all that she observed and all that she experienced of literary London in detailed ‘letters home’, intended to entertain her family in Florence.

An established reputation questioned

Throughout the 1880s and the 1890s Vernon Lee's reputation was enhanced, as she published supernatural and historical short fiction, travel impressions, and personal recollections, as well as essays on religious belief, aesthetics, and literary criticism. In 1884 alone she published three books: Euphorion, being Studies of the Antique and the Mediaeval in the Renaissance; The Countess of Albany, a biography of the Princess Louise of Stolberg; and Miss Brown, a three-decker novel about a beautiful servant–governess who is ‘discovered’ and subsequently educated by a wealthy aesthetic painter–poet. While the first two works were well received in literary circles, and are still considered among Vernon Lee's finest, Miss Brown was ‘a deplorable mistake’ (Gunn, 104) in the words of Henry James, to whom it was dedicated ‘for good luck’. She had seriously misjudged the response of those she had come to know among London's writers and artists. She had intended her first novel to be a thought-provoking satire of a ‘fleshly school’ of poetry and painting resembling the Pre-Raphaelites. Instead, many readers were shocked by her impropriety in presenting what appeared to be only thinly disguised caricatures of well-known people in an embarrassingly over-written novel. From the succès de scandale of Miss Brown, Vernon Lee's reputation was never fully to recover.

Aesthetic theory

Vernon Lee would also misjudge the popular response to her pioneering work in the field of psychological aesthetics, a development of the new ‘scientific’ school that had begun to dominate German aesthetic thought in the late 1870s. Her interest in the field grew out of the most significant love relationship of her life, her romantic friendship with Clementina (Kit) Anstruther-Thomson, a painter who was concerned with ‘what art does with us’, that is, with exploring the connection between the perception of artistic form and the human response. Beginning in the early 1890s, the two women, living together at least six months of every year in Florence and working as collaborators, undertook practical experiments to document physiological responses to art and studied psychology and physiology in order to learn the new methodology of experimentation and analysis. Their work would eventually lead them to discover ‘in an entirely empirical way ... the general principle of an aesthetics of empathy’ (Wellek, 169). Through their major publication together, Beauty and Ugliness and other Studies in Psychological Aesthetics (1912), they were to introduce this new aesthetics into an English aesthetic tradition that had long been dominated by Walter Pater's theories. But it is The Beautiful: an Introduction to Psychological Aesthetics (1913), commissioned as part of the Cambridge Manuals of Science and Literature series and written by Vernon Lee alone, that represents a more significant contribution to the advance of English aesthetics. It offers a brilliant synthesis of Vernon Lee's and Kit Anstruther-Thomson's principles of empathy with the latest theories of the German aestheticians. Yet this contribution has never been fully appreciated, except in histories of modern aesthetics, because its serious consideration demanded a difficult technical presentation. Even close friends such as Ethel Smyth and Irene Cooper Willis doubted the seriousness of the two collaborators' intentions and in later recollections of the two women's aesthetic experiments ridiculed them. Vernon Lee's immersion in psychological aesthetics would influence two other works by her—The Handling of Words and other Studies in Literary Psychology (1923), which, in adapting her methodology in the study of artistic form to the analysis of literary texts looks ahead to ‘new criticism’, and Music and its Lovers: an Empirical Study of Emotional and Imaginative Responses to Music (1932), which introduced terminology and perspectives from the aesthetics of artistic form into the aesthetics of music.

Travel and political writings

While originally defining herself as a cross between the bluestocking and the nineteenth-century man of letters, Vernon Lee's broadening interests in contemporary literary and social theory and in international politics gave her a new role as a twentieth-century intellectual. Her curiosity had led to her fascination with new developments in psychology, which, in turn, not only enriched her fiction but deepened her analysis of social and moral issues as her collections of essays, Gospels of Anarchy and other Contemporary Studies (1908) and Proteus, or, The Future of Intelligence (1925), demonstrate. To the role of woman of letters she added the dimension of travel writer, becoming one of the finest, most original of all time. She published seven collections of travel essays in her lifetime, from Limbo and other Essays in 1897 to The Golden Keys and other Essays on the Genius Loci in 1925. In each she transforms the conventional genius loci genre of travel writing through a unique sensitivity to place and a particularly graceful style. Vernon Lee's gift in these essays for easily combining imagination with great learning would later be admired by Aldous Huxley and Desmond MacCarthy, while Edith Wharton would pay tribute to what she had learned from her in her dedication of Italian Villas and their Gardens to ‘Vernon Lee, who, better than any one else, has understood and interpreted the garden-magic of Italy’ (1904, v). It is also significant that Irene Cooper Willis, one of Lee's closest friends, would recall Vernon Lee most clearly in the light of this special gift: ‘I see her best in my mind's eye, standing by some old building, wrapped in her homespun cloak ... waiting, entranced, for the spirit of place to take possession of her’ (‘Vernon Lee’, Colby Library Quarterly, June 1960, 115–16).

In the years just before the First World War, Vernon Lee added a political dimension to the role of woman of letters. Closely observing the death of Liberal England and the rise of the labour and suffrage movements, she used her pen in defence of women's equality, economic justice, international co-operation, and anti-militarism in a wide range of publications. During the war, she became a member of the anti-war Union of Democratic Control and a supporter of the women's peace crusade that would culminate in an International Congress of Women at The Hague. In 1915 she would write one of her most moving works, the anti-war morality play The Ballet of the Nations, and in 1920, setting it within a philosophical commentary, she republished it as Satan the Waster. In ‘Out of the limelight’ (1941), Desmond MacCarthy wrote of the work that it is ‘an anti-war classic’, ‘the most thorough literary analysis of war neurosis’ (Humanities, 1853, 192). Yet appearing when it did, so soon after the war, when few people were ready for self-examination, it fell into literary oblivion.

Death and reputation

Throughout the 1920s and early 1930s, Vernon Lee was painfully aware of her isolation and lack of power as a writer. She died on 13 February 1935 at her home, Villa Il Palmerino, Maiano, San Gervasio, Florence; after cremation her ashes were buried in the Allori cemetery in Florence in the grave of her half-brother, Eugene. Her rich and complex legacy still remains largely untouched. Desmond MacCarthy gives the best sense of it: ‘Mr Birrell once said that a man could live like a gentleman for a year on the ideas that he would find in Hazlitt; and the remark applies also to her. Her essays swarm with ideas’ (‘Out of the limelight’, 189). Still to be rediscovered are her individual masterly achievements such as the play Ariadne in Mantua and The Handling of Words, and the full range of her influence on other writers and artists is, as yet, unappreciated. Vernon Lee deserves to be recognized for the exceptional life she led as a woman of letters.

Phyllis F. Mannocchi

Sources

P. Gunn, Vernon Lee: Violet Paget, 1856–1935 (1964) · Vernon Lee's letters, ed. I. C. Willis (privately printed, London, 1937) [incl. preface by her executor [I. C. Willis]] · Colby College, Waterville, Maine, USA, Special Collections, Vernon Lee Collection · DNB · P. F. Mannocchi, ‘“Vernon Lee”: a reintroduction and primary bibliography’, English Literature in Transition, 1880–1920, 26 (1983), 231–67 · C. Markgraf, ‘“Vernon Lee”: a commentary and annotated bibliography of writings about her’, English Literature in Transition, 1880–1920, 26 (1983), 268–312 · W. V. Harris, ‘Eneas Sweetland Dallas (1829–79) and Vernon Lee (1856–1935)’, Victorian prose: a guide to research, ed. D. J. DeLaura (1973), 444–6 · V. Colby, ‘The puritan aesthete: Vernon Lee’, The singular anomaly: women novelists of the nineteenth century (1970), 235–304 · A. Fremantle, ‘Vernon Lee, a lonely lady’, Commonweal, 44 (1950), 297–9 · R. Wellek, ‘Vernon Lee, Bernard Berenson and aesthetics’, Discriminations: further concepts of criticism (1970), 164–86 · E. Smyth, What happened next (1940) · P. F. Mannocchi, ‘Vernon Lee and Kit Anstruther-Thomson: a study of love and collaboration between romantic friends’, Women's Studies, 12 (1986), 129–48

Archives

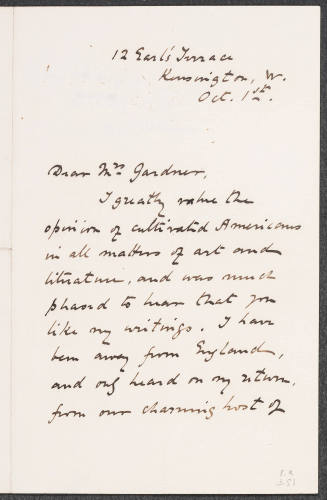

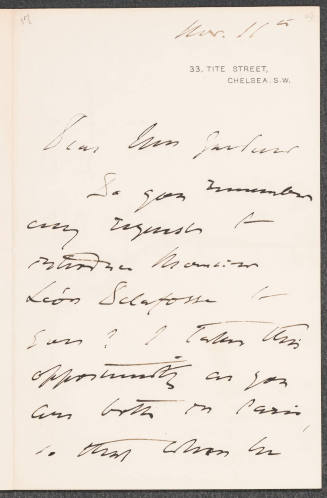

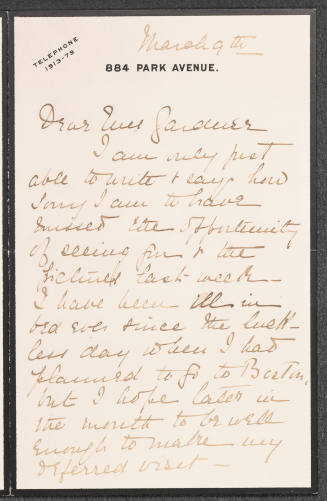

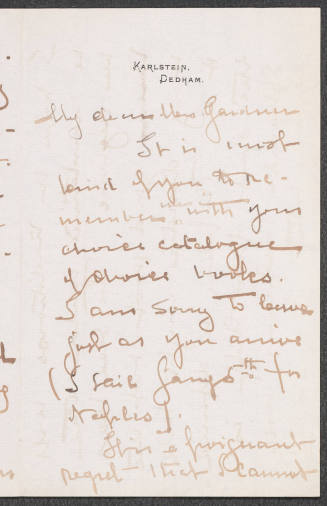

Colby College, Waterville, Maine, corresp., literary MSS, and papers · Somerville College, Oxford, corresp. and papers :: Bodl. Oxf., letters to various members of the Lewis family together with two MS articles · FM Cam., letters to E. J. Dent · Harvard U., Centre for Italian Renaissance Studies, letters to B. Berenson and M. Berenson · Hove Central Library, Sussex, letters to Lady Wolseley · NL Scot., corresp. with Blackwoods · Ransom HRC, corresp. with John Lane

Likenesses

J. S. Sargent, oils, 1881, Tate Collection [see illus.] · J. S. Sargent, pencil sketch, 1889, AM Oxf. · M. Cassatt, watercolour sketch, 1895; formerly priv. coll. · B. Noufflard, oils, 1934

Wealth at death

£5216 17s. 2d.: probate, 25 June 1935, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Phyllis F. Mannocchi, ‘Paget, Violet [Vernon Lee] (1856–1935)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2008 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2113/view/article/35361, accessed 8 Aug 2013]

Violet Paget [pseud. Vernon Lee] (1856–1935): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35361

[Previous version of this biography available here: October 2006]

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Florence, 1856 - 1925, London

Northamptonshire, 1851 - 1924, Oxford

Bristol, 1840 - 1893, Rome

Boston, 1862 - 1928, Sandwich

Portsmouth, England, 1828 - 1909, Box Hill, England

Philadelphia, 1855 - 1936, New York