John Addington Symonds

Bristol, 1840 - 1893, Rome

Family and education

The Symonds family descended from Adam Fitz Simon (d. before 1118), second son of Simon, lord of St Sever in Normandy, with land in Norfolk and Hertfordshire, specifically through the younger branch in Shropshire, eight generations of nonconformists who took up medicine as the main profession open to them. Symonds attributed his sense of duty to his sturdy puritan grandfather. His father was the most eminent physician in the west of England, and his social circle included eminent politicians, authors, scientists, historians, philosophers, and Christian socialists, among whom the young Symonds moved freely. From 1851 the family lived in the 1747 mansion of Clifton Hill House overlooking Bristol and the mouth of the Severn. Symonds's mother died in 1844, and her stern unimaginative sister raised the children. Strong bonds of sympathy developed between Symonds and his younger sister Charlotte, but his father had a powerful influence on the formation of his character, including his enthusiasm for Greek and Italian art. Symonds acquired culture as diligently as his father, who studied art, literature, and history two hours daily.

After private tutelage at Clifton, Symonds in May 1854 went to Harrow School, remembered for its philistine discomforts; there he was disturbed by the boys' sexual rough-housing. The headmaster Charles Vaughan's affair with one of the boys appalled Symonds because of Vaughan's hypocrisy and because it threatened the idealization of homosexual love that Symonds was formulating with the help of Plato's Symposium and Phaedrus. Symonds dated the birth of his real self from spring 1858, when he fell in love with Willie Dyer, a chorister at Bristol Cathedral. He confessed his romantic affection to his father, who persuaded him gradually to end the affair. In 1859 Symonds revealed the story about Vaughan to a friend during an argument about ‘Arcadian love’, and was persuaded to tell his father, who forced Vaughan to resign his headmastership and hindered his subsequent career. Symonds was traumatically upset by these events, but concluded that his own role stemmed from carelessness rather than treachery.

Symonds went to Balliol College, Oxford, in autumn 1858, and began a lifelong friendship with its master, Benjamin Jowett; he became distinguished in classics and won the Newdigate prize for his poem ‘The Escorial’ (1860). He became a fellow at Magdalen College (1862–3), and received the chancellor's prize for his essay ‘The Renaissance’. Unsuccessful attempts to repress his forbidden desire for another cathedral chorister, Alfred Brooke, damaged his nervous constitution, and in 1863 his health collapsed, exacerbated by stress caused by the ensuing gossip. For three years a painful eye inflammation prevented serious work. Dr Spencer Wells, surgeon to the queen's household, diagnosed his disorders as resulting from sexual repression, and Symonds was advised to attempt the ‘cure’ of marriage. The role played by sexual repression and anxiety in a long series of physical and mental breakdowns should not be exaggerated, however, for nervous irritability and pulmonary disease were frequent on both sides of his mother's family: Symonds was to die of tuberculosis just as did his grandfather James Sykes, his sister Mary Isabella, and his own daughter Janet.

From 1860 to 1863 Symonds travelled in search of health to Belgium, Germany, Austria, France, Italy, and Switzerland, where in 1863 he met (Janet) Catherine North (1837–1913), second daughter of Frederick North, Liberal MP for Hastings, and Janet Marjoribanks of Ladykirk, Scotland. He and Catherine North married in St Clement's Church, Hastings, on 10 November 1864. Symonds could not alter his sexual orientation, and his haggard features in photographs from this period make painfully visible the strain of accommodating himself to conventional life. The couple settled in London, at 7 Half Moon Street in 1864, then at 47 Norfolk Square from January 1865. Symonds attempted to study law, but in 1865 his left lung was diagnosed as tubercular. In 1868, after another physical and nervous breakdown, they moved to 7 Victoria Square, Clifton. There he lectured on Greek art at Clifton College (1869) and at the Society for Higher Education for Women, and pursued a four-year affair with the Clifton schoolboy Norman Moor. Catherine and Symonds had four children, Janet (b. 1865), Charlotte (b. 1867), Margaret (b. 1869), and Katharine [see Furse, Dame Katharine], but in 1869 Catherine and Symonds agreed to a platonic marriage, while he would have male companions. Photographs of Symonds in Venice at this time demonstrate that he grew in health and vigour as he was freed from deceit and repression. Catherine and the children holidayed in Ilfracombe while Norman Moor and her husband spent much of each year together in Italy and Switzerland. Catherine initially expressed resentment, but grew to accept the arrangement; Margaret later said that her mother had possessed ‘singular Sibylline fortitude’ (M. Symonds, 163). Dr Symonds died in February 1871 and the Symonds family moved into Clifton Hill House in September.

Early writings

During the 1860s Symonds contributed to various periodicals; bad health suggested writing as his best hope for a career, which he consolidated during the 1870s. His Clifton lectures produced his first two books, An Introduction to the Study of Dante (1872) and Studies of the Greek Poets (1873), followed by Sketches in Italy and Greece (1874), Renaissance in Italy: the Age of the Despots (1875), and Studies of the Greek Poets, Second Series (1876). He withdrew his nomination for the professorship of poetry at Oxford in 1876 when he was violently attacked for defending paiderastia in the last chapter of Studies of the Greek Poets. The breadth and depth of his scholarship were acknowledged, but he was considered to be too bohemian and unconventional. Andrew Lang said that Symonds ‘seems to us to be too fond of alluding to the unmentionable’ (The Examiner, 23 June 1877). As his Italian studies progressed, critics rebuked him for unearthing ‘scandals’ and ‘filth’; publication of his discovery in the Buonarroti archives that Michelangelo's poems and letters had been deliberately altered so as to obscure masculine love was deemed mischievous.

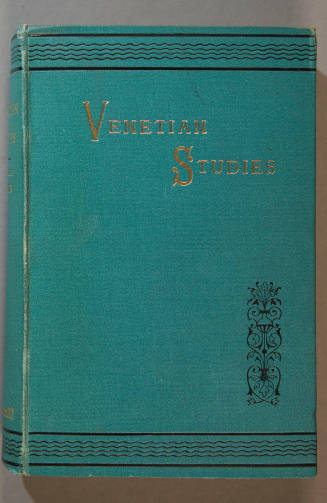

Symonds wrote popular rather than academic works; their extraordinary vividness sometimes becomes too picturesque. A gift for dramatized sketches enlivens his massive history of the Renaissance in Italy (The Age of the Despots, 1875; The Revival of Learning, 1877; The Fine Arts, 1877; Italian Literature, 2 vols., 1881; Catholic Reaction, 2 vols., 1886). Acknowledging his debt to Jacob Burckhardt, Hegel, and Darwin for ‘evolutionary’ history, Symonds celebrated paganism over Christian superstition, radically challenging Ruskin's Christian view of historical progress. He found within the Renaissance the roots of the modern perception that sexuality is in harmony with nature. The digressions and unevenness of this first Kulturgeschichte in English stem largely from Symonds's pursuit of references to homosexuality; his history of art embodies a theory of sexual liberation. Detection of ‘the aura’ similarly inspired most of his literary criticism.

In 1877 bronchitis brought on a violent haemorrhage, and Symonds dared not spend another winter in England. A journey aiming for Egypt was broken at Switzerland, at Davos Platz. He revisited Davos in 1878, and in 1880 settled there permanently, living first at Hotel Buol (Christian Buol became a companion). His own house (built in June–September 1881), called Am Hof after its meadow, became his home for the rest of his life. In Davos he helped many young men get a foothold in business, paid for the Davos Gymnasium, and took great pleasure in the physical life as president of the Winter Sports Club and Toboggan Club. Davos prospered as a winter resort through his magazine articles. Life at Am Hof was free from taboos, and Katharine knew the nature of her father's studies from the age of six. All topics were fully discussed, be they:

the English Church, or the poems of Walt Whitman, or homosexuality, or the chimney sweep, or toboggan races ... words like ‘neurotic’, ‘neuropathic’, and ‘psychopathic’, were in common parlance at Am Hof before they came into general use outside, even in medical circles. (Furse, 98–9)

Each spring and autumn the Symonds family rented the mezzanine floor of Ca' Torresella, 560 Zattere, overlooking the canal of the Guidecca, Venice, owned by Horatio Forbes Brown (1854–1926), Symonds's closest friend from 1872 (openly homosexual himself, though they were not lovers). Symonds played the padrone with scores of stevedores, gondoliers, hotel porters, and peasant mountaineers. In May 1881 he fell in love with Angelo Fusato (1857–1923), a handsome Venetian gondolier. With financial help from Symonds, Angelo was able to marry his mistress who had borne him two sons. Symonds hired Angelo as his gondolier and the two men openly lived and travelled together. Angelo remained Symonds's companion until Symonds's death, and Margaret and Katharine remembered him with affection.

Symonds's inheritance and regular income from investments were comfortable: he had increased his capital estate by £22,000 from 1877 to 1892, and had invested £2200 in 1892; most of his stocks were in land and railways; his earnings from literature that year were only £500, which he used to set up a gondolier in business (Letters, 3.762). He earned little from writing until his last few years, and scrupulously spent only his literary earnings on Angelo and other young men. Two Swiss farms provided security for the children.

Writings on homosexuality and literature

The years at Am Hof were productive, though marked by Symonds's distress for Janet, who was diagnosed tubercular in 1883 and died in 1887. A Problem in Greek Ethics (written 1873, ten copies printed 1883), the first history of homosexuality in English, carefully argues that if homosexual relations were honourable in ancient Greece, they cannot be diagnosed as morbid in modern times. In 1889, inspired by the candour of The Memoirs of Count Carlo Gozzi which he translated (2 vols., 1890), Symonds began his own autobiography, not as a memoir of daily events but as a psychological study of ‘self-effectuation’, unique in its frankness. A Problem in Modern Ethics (1891, 50 copies) is the first ‘scientific’ psychological–sociological analysis of homosexuality in English, exposing vulgar errors by a well-judged mixture of sarcasm, science, and common sense. In June 1892 Symonds proposed that Havelock Ellis, editor of the Contemporary Science Series, publish a book on ‘Sexual inversion’ by him, because the subject ‘is being fearfully mishandled by pathologists and psychiatrical professors, who know nothing whatsoever about its real nature’ (Letters, 3.691). They decided to collaborate, but Symonds died before the project took final shape.

In addition to works already mentioned, Symonds wrote books on Boccaccio, pre-Shakespearian drama, and Walt Whitman (1893); critical introductions to works by Sir Thomas Browne, Marlowe, Heywood, Webster, and Tourneur, and the ‘Uranian’ poet Edward Cracroft Lefroy; evocative travel sketches and Our Life in the Swiss Highlands (1892, with his daughter Margaret); short biographies of Shelley (1878), Sir Philip Sidney (1886), and Ben Jonson (1886); masterly translations of The Sonnets of Michael Angelo Buonarroti and Tommaso Campanella (1878), and The Life of Benvenuto Cellini (2 vols., 1888). He also produced articles for the Encyclopaedia Britannica on Ficino, Filelfo, Guarini, Guicciardini, Machiavelli, Manutius, Metastasio, Petrarch, Poggio, Politian, Pontanus, the Renaissance, Tasso, and the history of Italy from 476 to 1796.

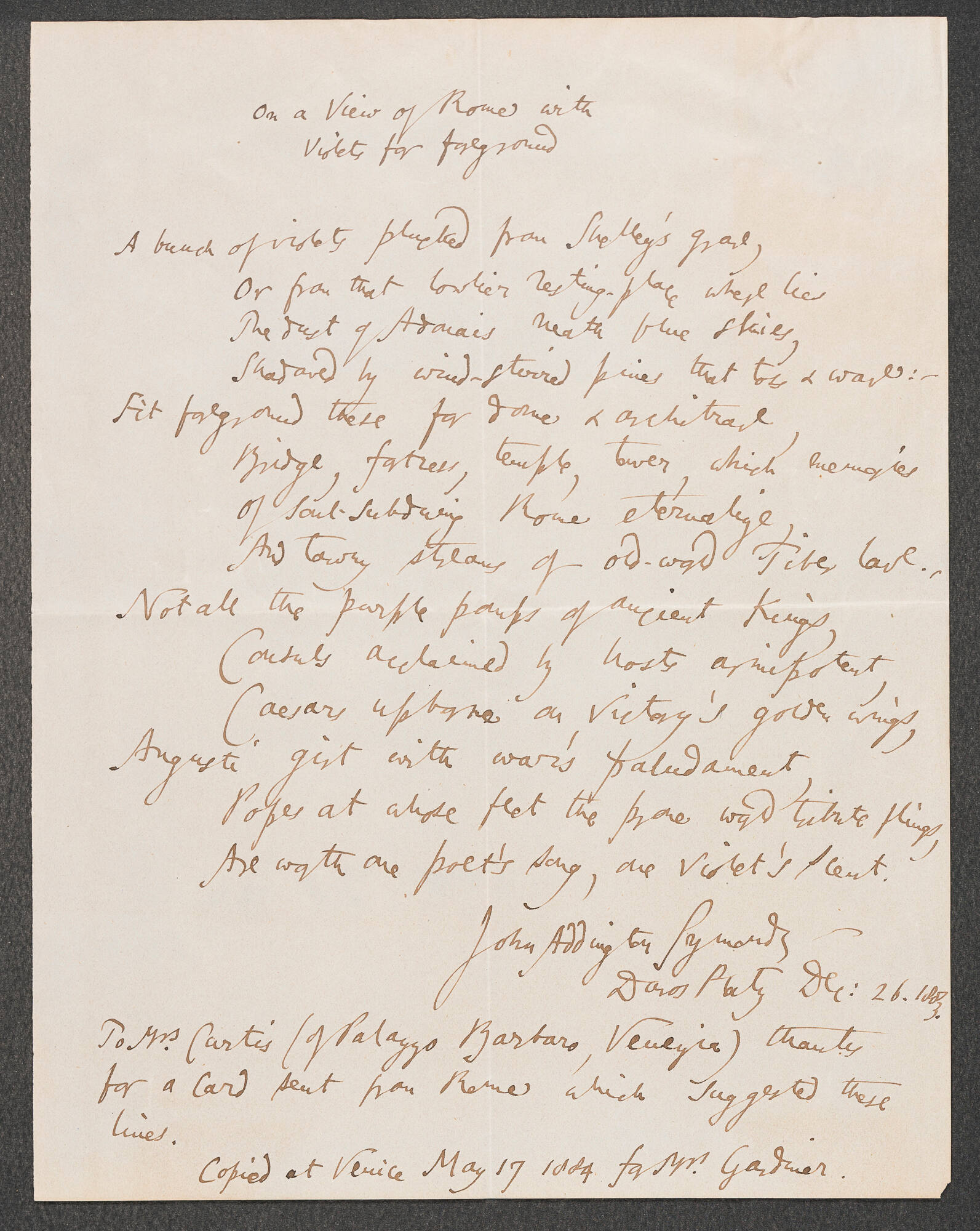

Writing poetry gave Symonds great joy, but his poetry is not successful. His unpublished and privately printed ‘Uranian’ verse is derivative of Marlowe's Hero and Leander (‘Eudiades’) and frankly masturbatory (‘Phallus impudicus’); friends persuaded him to destroy some of it. He published many tightly knitted intellectual sonnets in the manner of the seventeenth-century metaphysical poets. Though Symonds had been frankly sceptical of all religions since the mid-1860s—he did not believe in a personal God or in specifically Christian tenets—his Whitmanesque ‘Cosmic Enthusiasm’ pervades his poetry to an almost mystical degree. He disguised his homosexual sentiments with gnomic abstractions; ‘unutterable things’, ‘valley of vain desire’, ‘l'amour de l'impossible’, ‘Chimaera’, and ‘Maya’ are his codes for homosexual desire. Using this key, it can be appreciated how Many Moods (1878), New and Old (1880), Animi figura (1882), Fragilia labilia (1884), and Vagabunduli libellus (1884) trace Symonds's evolution from repression and self-loathing to self-realization and celebration. He felt ‘very bitter’ that homosexual poets had ‘to eviscerate their offspring, for the sake of ... an unnatural disnaturing respect for middleclass propriety’ (Letters, 3.450–51). The sonnet sequence ‘Stella Maris’ (in Vagabunduli libellus), charts the progress of his affair with Angelo Fusato in 1881, though ‘Many of these sonnets were mutilated in order to adapt them to the female sex’ (Memoirs, 272).

Character and achievement

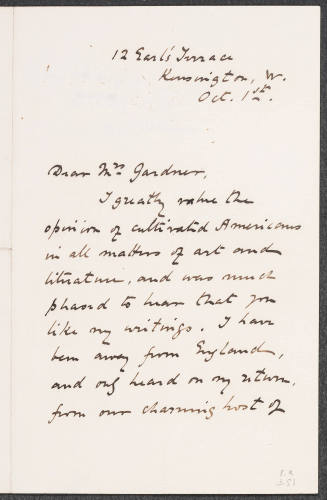

Despite a naturally introspective temperament, Symonds was full of joie de vivre. Jowett declared that no one cherished friends more than he, and Robert Louis Stevenson (a fellow invalid at Davos) found him a delightful conversationalist. Affectionate and long-lasting friendships were established with women as well as men, such as Margot Tennant and Janet Ross, the latter of whom said that ‘his talk was like fireworks, swift and dazzling, and he had a wonderful gift of sympathy’ (Grosskurth, 304). Many photographs capture his slight build, frail but indomitable features, and apprehensive expression.

Symonds's lungs grew steadily weaker, while he worked at a killing pace in December 1892 on his monumental biography of Michelangelo (2 vols., 1893). During a lecture tour in April 1893 he caught influenza in Rome, and pneumonia engulfed both lungs; he died in his room at the Albergo d'Italia, via Quattro Fontane 12, Rome, on 19 April 1893, with Angelo at his side. The funeral was delayed until Catherine (who had fallen ill in Venice) and Charlotte arrived, and he was buried in the protestant cemetery on 22 April, a few steps below Shelley's grave; Jowett provided the epitaph.

Though a third of Symonds's waking life was spent recuperating from illness, his output was prodigious. In twenty years he wrote nearly forty books, plus uncollected reviews and unpublished poems, and more than 4000 letters, of which half survive especially to his friends Henry Graham Dakyns, Henry Sidgwick, Walt Whitman (whose work he popularized), Edmund Gosse, Robert Louis Stevenson and his wife, Samuel Richards, Vernon Lee (Violet Paget), Mary Robinson, and Arthur Symons. He told his sister Charlotte, ‘I had hoped to make my work the means of saving my soul’ (Letters, 2.310).

Symonds wrote to Catherine on the day he died, stressing that Brown, his literary executor, was to receive:

all Mss Diaries Letters & other matters found in my books cupboard ... I do this because I have written things you could not like to read, but which I have always felt justified and useful for society. Brown will consult & publish nothing without your consent. (Letters, 3.839)

Catherine required that the autobiography be suppressed. Brown wrote his biography of Symonds, as Sir Charles Holmes recorded, ‘exercis[ing] little more than ordinary discretion in cutting out the most intimate self-revelations. But a straiter critic had then to take a hand. The proofs, already bowdlerized, were completely emasculated’ (Furse, 98)—probably by Edmund Gosse. With the homosexual backbone missing from Brown's biography (2 vols., 1895), readers were puzzled by the intensity of Symonds's quest for ‘the Whole’.

The Ellis/Symonds material was published under both names first in Germany as Das konträre Geschlechtsgefühl (1896), then in London as Sexual Inversion (1897), with ‘A problem in Greek ethics’ as an appendix, and case histories collected by Symonds (Case XVIII, pp. 58–63, is his own). The English edition was bought up by Brown on the eve of publication to avoid scandal. Later in 1897 it was published as Studies in the Psychology of Sex. Vol. I. Sexual Inversion. By Havelock Ellis, with Symonds's name wholly expunged at Brown's insistence. Symonds's historical, cultural, and social material was omitted, and Ellis's medical model of homosexuality as a congenital neurosis prevailed. A bookseller was successfully prosecuted for selling this edition, which was suppressed as an ‘obscene’ work. The two revised Problem essays were surreptitiously printed by Leonard Smithers in 1896 and again in 1901 and Ellis's Sexual Inversion was published in Philadelphia (1901).

Brown died in 1926, bequeathing the autobiography and other Symonds papers to London Library, with instructions that nothing be published for fifty years. Charles Hagberg Wright, the librarian, and Edmund Gosse, chairman of the committee, burnt all these papers except the autobiography. The embargo expired in 1976, and in 1984 about four-fifths of the autobiography were published, edited by Phyllis Grosskurth, omitting many poems on youths, early descriptive writings, transcripts of letters sent to Symonds, letters sent by him to his wife, testimonials on several of his academic friends, and much material about Christian Buol.

Though Symonds's biography of Michelangelo and his translation of Michelangelo's sonnets and Cellini's autobiography were ‘standard classics’ for a century, and The Renaissance still provokes scholarly discussion, Symonds's studies of homosexuality and his autobiography are his most important contributions to modern ideas. The initial suppression of these writings has obscured his place as a pioneer in the sexual reform movement. Like many Victorian ‘bourgeois radicals’, Symonds felt a responsibility for reforming public opinion. He discreetly lobbied for the repeal of the laws against homosexuality, and rebuked friends and colleagues when they expressed anti-homosexual prejudice or ignorance. He was one of the first people openly to advocate homosexual emancipation in Britain, insisting that homosexuality was a natural ‘minority’ rather than an ‘abnormality’.

Rictor Norton

Sources

The letters of John Addington Symonds, ed. H. M. Schueller and R. L. Peters, 3 vols. (1967–9) · ‘Memoirs of John Addington Symonds’, MS, 2 vols., London Library [pt-pubd as The memoirs of John Addington Symonds, ed. P. Grosskurth (1984)] · P. Grosskurth, John Addington Symonds: a biography (1964) · J. A. Symonds, On the English family of Symonds (1894) · Miscellanies by John Addington Symonds, M.D. (1871) [with introductory memoir] · M. Symonds, Out of the past (1924) · K. Furse, Hearts and pomegranates (1940) · H. F. Brown, John Addington Symonds: a biography, 2 vols. (1895) · Letters and papers of John Addington Symonds, ed. H. F. Brown (1923) · J. G. Younger, ‘Ten unpublished letters by John Addington Symonds [to Edmund Gosse] at Duke University’, Victorian Newsletter, 95 (1999), 1–10 · P. L. Babington, Bibliography of the writings of John Addington Symonds (1925) · C. Markgraf, ‘John Addington Symonds: an annotated bibliography of writings about him’, English Literature in Transition, 1880–1920, 18 (1975), 79–138 · C. Markgraf, ‘Update’, English Literature in Transition, 1880–1920, 28 (1985), 59–78

Archives

BL, notebook, RP2872 [copies] · BL, translation of life of Benvenuto Cellini, Add. MSS 40649–40652 · Bodl. Oxf., commonplace book · Bodl. Oxf., corresp. and papers · Bodl. Oxf., letters · Harvard U., Houghton L., Miscellanies, no. 3 · London Library, memoirs · London Library, memoirs and MS work on philosophy · University of Bristol, corresp., literary MSS, and papers · University of Bristol, family papers :: BL, letters to Macmillans, Add. MSS 55253–55255, 55258 · BL, letters to R. L. Stevenson and Fanny Stevenson, Ashley MS 5764 · Bodl. Oxf., letters and typescript copies of letters to Margot Asquith · Bodl. Oxf., letters to Roden Noel · Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, letters to Curtis family · JRL, letters to J. L. Warren · King's AC Cam., letters to Oscar Browning · priv. coll., letters to Henry Graham Dakyns and unpublished poetry · U. Birm. L., annotated copy of R. L. Stevenson's Virginibus puerisque · U. Leeds, Brotherton L., letters to Edmund Gosse

Likenesses

Vigor, oils, 1853, University of Bristol · S. Richards, pen-and-ink drawing, 1890, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis; repro. in Letters, ed. Schueller and Peters, vol. 2, frontispiece · photograph, 1892, repro. in Letters and papers, ed. Brown, frontispiece · J. Brown, stipple (after drawing by E. Clifford), NPG · E. Myers, photograph, NPG [see illus.] · C. Orsi, chalk drawing, NPG · photographs, University of Bristol; repro. in Grosskurth, John Addington Symonds, facing p. 279

Wealth at death

£75,666 2s. 1d.: resworn probate, Nov 1893, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Rictor Norton, ‘Symonds, John Addington (1840–1893)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2013 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/26888, accessed 6 Aug 2013]

John Addington Symonds (1840–1893): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/26888

[Previous version of this biography available here: May 2006]

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Boston, 1825 - 1908, Venice

Paris, 1874 - 1965, Nice, France