Janet Ross

London, 1842 - 1927, Florence

found: Queen bee of Tuscany, 2013: page 266 (died August 23) Jacket (born in England, married and moved to Egypt then Florence, Italy; writer, historian)

Oxford DNB, accessed 8/29/2017

Ross [née Duff Gordon], Janet Ann (1842–1927), traveller and author, was born on 24 February 1842 at 8 Queen Square, London, the daughter of Alexander Cornewall Duff Gordon (1811–1872), and his wife, Lucie Austin [see Gordon, Lucie Duff (1821–1869)]. Her parents moved in prominent social and literary circles: her father, a Treasury clerk and later a commissioner for the Inland Revenue, was from a patrician family, while her mother was the only daughter of the jurist John Austin (1790–1859) and the German translator Sarah Austin (1793–1867); Lucie Duff Gordon later became the writer of the celebrated Letters from Egypt (1865). Her siblings, Maurice and Urania, were not born until some years later, and Janet Duff Gordon spent her childhood as ‘a spoiled and rather lonely child’ (Ross, Fourth Generation, 7); her friends were distinguished adults, including Caroline Norton, W. M. Thackeray, Tom Taylor, and Richard Doyle. She attended tea parties held by the Miss Berrys and breakfasts by Samuel Rogers, and was acquainted with a circle of celebrities including Amelia Opie, Charles Babbage, and Thomas Carlyle (whom she disliked, considering him to be rude to her mother).

Soon after moving from Queen Square to Esher in the early 1850s, the Duff Gordons realized that they had neglected their daughter's education. They hired a German governess and later sent Janet to spend a year at a school in Dresden; in 1856 she was taken to Paris to learn French. Although she was a natural linguist—publishing a translation of a work by Heinrich von Sybel in 1861—it was clearly too late for education to turn her into a model maiden. A daring enthusiast for outdoor sports, especially riding, hunting, and fishing, Janet Duff Gordon had developed into a highly unconventional young woman, with a free and easy manner which offended mature ladies. She cultivated an extraordinarily diverse collection of men friends, addressed her father as ‘dear old boy’, and moved with a staggering lack of awe among a glittering circle of artistic, literary, and political celebrities. She picnicked on the River Mole with Millais, Doyle, and Ary Scheffer; spent a winter with the Tennysons, becoming devotedly attached to the invalid Mrs Tennyson; and visited the Lansdownes at Bowood House. Here she rode with the duke of Beaufort's hounds and was sketched by G. F. Watts for the Bowood frescoes (with a canny appreciation of her androgynous appeal, he cast her as Patroclus). A. W. Kinglake and A. H. Layard became lifelong and doting friends, while George Meredith (who fell deeply in love with her) portrayed her as Rose Jocelyn in his semi-autobiographical novel Evan Harrington (1860).

At a dinner in 1860 Janet Duff Gordon met Henry James Ross (1820–1902), a friend of Layard. His tales of pig-sticking in Egypt proved to be irresistible, and she invited him to stay at Esher. Here they hunted together, and, ‘impressed by his admirable riding, his pleasant conversations, and his kindly ways’ (Ross, Fourth Generation, 84), she accepted his proposal of marriage, despite his twenty years' seniority. They were married at Ventnor on 5 December 1860. This astonishing match was met with pained generosity by Kinglake and Meredith, who were further afflicted by her immediate departure to take up residence in Egypt. The couple had only one child, Alick; it seems probable that the unconventional Janet resorted to contraceptives after a miscarriage during her second pregnancy. The appeal of Eastern adventure may well explain Janet Ross's marriage. After the couple landed in Alexandria in January 1861, she immediately began to pick up ungrammatical Arabic from her house-boy and visited Cairo, which reminded her inevitably of the Arabian Nights. She rode desert races against Egyptian pashas, met the historian Henry Buckle on his travels, mounted a camel to see the Suez Canal under construction, and acted as the Egyptian correspondent for The Times.

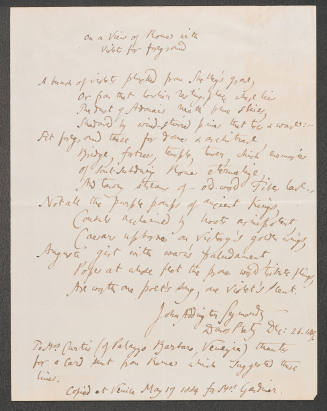

By the mid-1860s the bank in which Henry Ross was a partner was in difficulties; the couple decided to cut their losses and retire to Italy. By September 1869 they had settled in an apartment in Florence on the Lung'Arno Torrigiani, where they mixed in Anglo-Florentine literary, artistic, and social circles; in the early 1870s they rented a villa at Castagnolo, and in 1888 they bought their own property, Poggio Gherardo, near Settignano, where Janet spent the rest of her life. A quieter country life suited Henry Ross, who wanted to cultivate orchids, and Janet soon began to study the agricultural life of Tuscany, assisting with the olive and grape harvests and collecting Tuscan peasant songs, which she sang to visitors, accompanying herself on the guitar. She established a wide circle of friends and a plethora of interests: among many visitors were the future Lady Butler, the artist; the collector and connoisseur of Spanish art Sir William Stirling-Maxwell; and J. A. Symonds, whom Janet met in 1882. A friendship with Ouida was wrecked when the flamboyant novelist fell ostentatiously in love with an Italian marquess and began to view Janet as a rival, portraying her vengefully as an aristocratic adventuress in Friendship (1878).

During these years Mrs Ross established herself as a minor figure in the Anglo-Florentine literary world and played a part in looking after the aged W. E. Gladstone on his final visit to Florence. Such publications as Italian Sketches (1887) and Old Florence and Modern Tuscany (1904)—collections of essays which had appeared earlier in English periodicals—reflected her Italian life and interests, mingling short historical pieces on Florentine art and culture and accounts of visits to Italian tourist spots with more unusual descriptions of oil-making in Tuscany and the land tenure system known as mezzaria. Leaves from our Tuscan Kitchen (1899) was her most significant publication in this practical vein: a collection of local vegetable recipes dictated to her by her chefs, it became a classic in its field. The Land of Manfred (1889)—a more conventional historical-cum-travel narrative of a tour of south Italy—is nevertheless remarkable for its exploration of a then neglected area; lively and well illustrated, it is one of the most readable of her works. With Nelly Erichsen she collaborated to produce two volumes in Dent's Medieval Towns series, The Story of Pisa (1909) and The Story of Lucca (1912). The most erudite of her publications was The Letters of the Early Medicis (1910): researched extensively in Florentine libraries, it contained translations of hitherto unpublished Medici letters and benefited from the assistance of scholarly friends such as T. M. Lindsay. Janet Ross had first met this endearing Scottish historian in 1906, and they remained in correspondence until his death in 1914.

Other publications resulted from an interest in the lives and works of her family. Janet Ross published editions, with memoirs, of her mother's works and edited her husband's Letters from the East (1902). In 1888 she produced the monumental Three Generations of Englishwomen, a triple biography of her mother, her grandmother (Sarah Austin), and her great-grandmother (Susannah Taylor of Norwich): based on and containing family papers, it remains the most important source for the lives of these three women of letters. An autobiographical sequel, The Fourth Generation (1912), followed, which expanded the more lightweight Early Days Recalled (1891).

Henry Ross died on 2 July 1902. Janet Ross's later years were not untroubled ones. On a nostalgic visit to Egypt in 1903–4 she found much changed, and soon after Henry's death she argued with her niece Lina, who had been living with her for a decade, over the latter's engagement to the artist Aubrey Waterfield. Although now rather isolated at Poggio Gherardo, Janet Ross did not always appreciate the visits which she received as the acknowledged doyenne of Anglo-Florentine society. However, an intimacy grew up with the Berensons at the nearby Villa I Tatti (rebuilt with a loan from Janet Ross) and she also showed great partiality for the young Kenneth Clark, who described her as ‘a well-known terrifier’ (Clark, 125). Mrs Ross was later reconciled to her niece: Lina Waterfield and her two children came to live at Poggio Gherardo during the First World War, and aunt and niece were both involved in the foundation of the British Institute in Florence. After the war, the political unrest of Italy began to touch upon Janet Ross's life: her initial tendency to favour fascism was reversed when blackshirts intruded into her house, demanding money. After several months of ill health, she died at her home on 23 August 1927, leaving Poggio Gherardo to Lina and her son. Janet's own son, Alick Ross, disputed the legacy, and legal costs and high taxes eventually forced Lina to sell it in 1946.

‘Handsome ... [with] classical features and ... thickly marked eyebrows accentuating the earnestness of her gaze’ (Waterfield, 54), Janet Ross was, according to her niece, ceaselessly active, practical, and as regular as clockwork. Despite an irresistible joie de vivre and an exceptional talent for friendship, she had no understanding of romantic passion, limited imagination, and curiously little appreciation for beauty (she was apparently unmoved by the beautiful views surrounding Poggio Gherardo). Kenneth Clark described her as ‘the most completely extrovert human being I have ever known ... her passions had passed like water off a duck's back’ (Clark, 126). Formidable yet approachable, cultured but not erudite, she was an unconventional and vital Victorian woman who used her privileged social standing, intellectual background, and attractive appearance to achieve the fullest life available to her. Her publications were second rate, but her life was certainly not.

Rosemary Mitchell

Sources

J. Ross, The fourth generation (1912) · L. Waterfield, Castle in Italy: an autobiography (1961) · J. Ross, Early days recalled (1891) · Letters of principal T. M. Lindsay to Janet Ross (1923) · J. A. Ross, Three generations of Englishwomen: memoirs and correspondence of Mrs John Taylor, Mrs Sarah Austin and Lady Duff Gordon, 2 vols. (1888) · K. Frank, Lucie Duff Gordon: a passage to Egypt (1994) · J. Ross, Leaves from our Tuscan kitchen, rev. M. Waterfield, rev. edn (1973), preface · K. Beevor, A Tuscan childhood (1993) · K. Clark, Another part of the wood (1974); repr. (1985) · Burke, Peerage (1907) · M. Secrest, Being Bernard Berensen (1979) · Gladstone, Diaries

Likenesses

C. Norton, pen-and-ink sketch, c.1850, repro. in Ross, Fourth generation, facing p. 12 · G. F. Watts, watercolour?, 1856–9, repro. in Ross, Fourth generation, facing p. 40 · G. F. Watts, chalk sketch, 1858, repro. in Ross, Fourth generation, facing p. 49 · F. Leighten, chalk sketch, 1860–69, repro. in Ross, Fourth generation, facing p. 172 · photograph, 1862, repro. in Ross, Fourth generation, facing p. 130 · V. Prinsep, pencil sketch, 1865, repro. in Ross, Fourth generation, facing p. 155 · F. Crisp, watercolour, c.1908, repro. in Ross, The fourth generation, frontispiece

Wealth at death

£1212 2s. 5d.: probate, 16 May 1928, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Portsmouth, England, 1828 - 1909, Box Hill, England

Bristol, 1840 - 1893, Rome

Villers-Cotterêts, France, 1802 - 1870, Dieppe, France

Worcester, 1870 - 1945, Lancing