Max Beerbohm

London, 1872 - 1956, Rapallo

Education and early years

From 1881 to 1885 Max—he was always called simply Max and it is thus that he signed his drawings—attended the day school of a Mr Wilkinson in Orme Square. Mr Wilkinson, Max said, ‘gave me my love of Latin and thereby enabled me to write English’ (Rothenstein, 370–71). Mrs Wilkinson taught drawing to the students, the only lessons Max ever had in the subject. In 1885 he entered Charterhouse School, where, in spite of his aversion to athletics, he seems to have been reasonably happy, even though he later wrote: ‘My delight in having been at Charterhouse was far greater than my delight in being there ... I always longed to be grown-up!’ (Beerbohm, Mainly on the Air, 151, 154). At Charterhouse he found pleasure and escape in reading, especially Thackeray (who had himself gone to Charterhouse and was also an illustrator). And he took to drawing caricatures, of other boys, of the schoolmasters, and of public figures, especially the prince of Wales, later Edward VII.

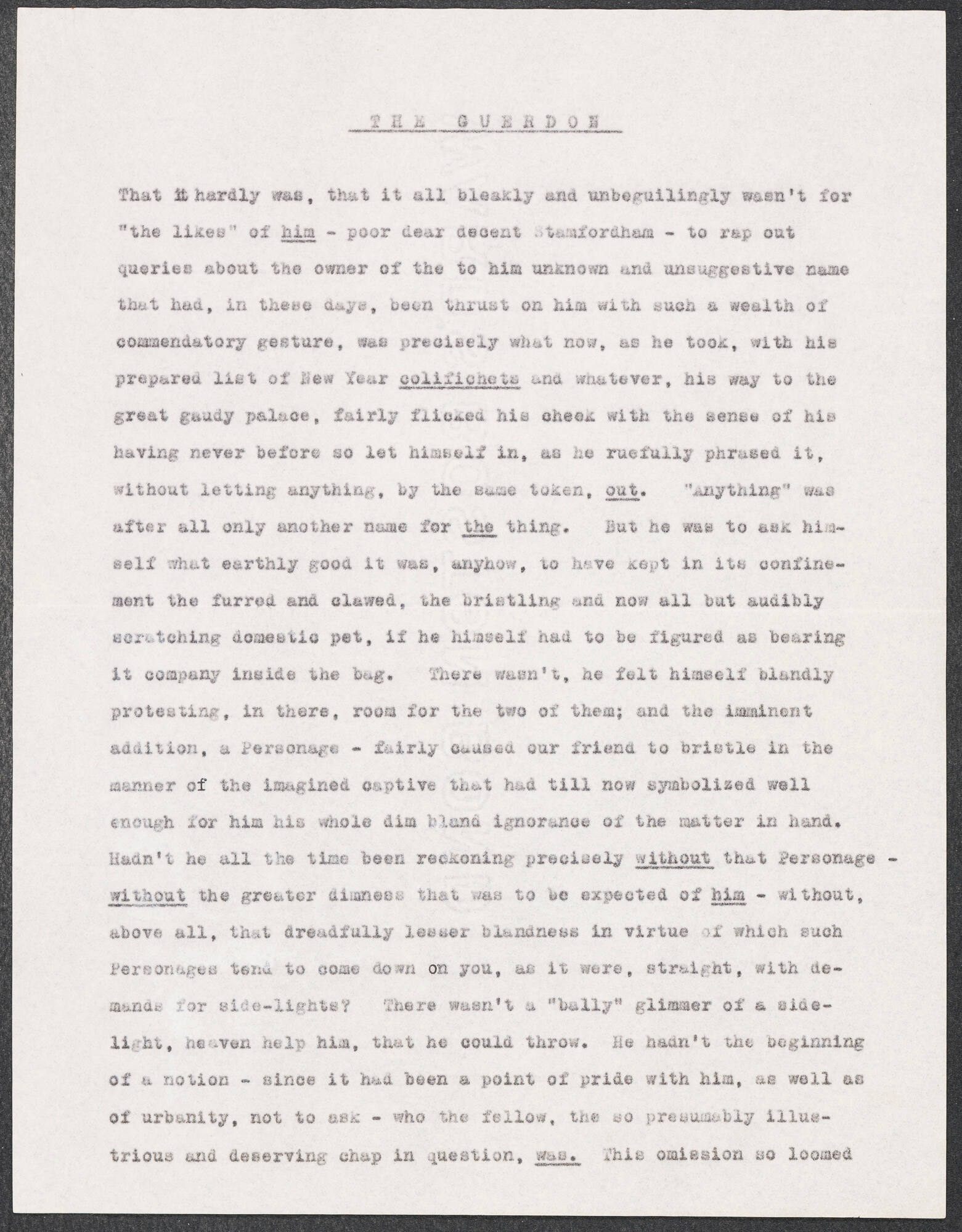

In 1890 Max went up to Merton College, Oxford, to study classics. He loved Oxford. ‘Undergraduates,’ he wrote, ‘owe their happiness chiefly to the consciousness that they are no longer at school. The nonsense which was knocked out of them at school is all put gently back at Oxford or Cambridge’ (Beerbohm, More, 156). Max found ‘this little city of learning and laughter’ the perfect place for the development of his dandyism, his aestheticism, his distinctive spectator persona. At Merton, Max came to know the man who was to be his dearest friend, the novelist Reggie Turner. Through Turner, Max became friends with Oscar Wilde and his inner circle, which comprised art critic Robert Ross, Lord Alfred Douglas, and Turner. In Max's third year at university, the artist William Rothenstein arrived from Paris to draw portraits of Oxford ‘characters’ (eventually including Max among them). Rothenstein became another close and life-long friend.

Max's career as a professional caricaturist began when he was twenty: in 1892 the Strand magazine published a series of his drawings of ‘club types’—thirty-six in all. Their publication dealt, Max said, ‘a great, an almost mortal blow to my modesty’ (M. Beerbohm, ‘When 9 was nineteen’, Strand Magazine, October 1946, 51). In 1893 Rothenstein introduced him to the publisher John Lane, who was about to launch The Yellow Book. Max contributed essays to its first and later volumes. He also wrote for other publications, and he drew caricatures for The Yellow Book, Pick-Me-Up, Sketch, and the Pall Mall Budget. Then in 1896 he published, under the imprint of John Lane, a collection of essays, disarmingly named The Works of Max Beerbohm, and, under the imprint of Leonard Smithers, a collection of drawings, Caricatures of Twenty-Five Gentlemen. He was famous at twenty-four.

Max never made much money. A freelance writer and artist, he held only one regular job in his lifetime: from 1898 to 1910 he was drama critic for the Saturday Review, on the recommendation of his predecessor, George Bernard Shaw. Max's first column explained with nice irony how unfit he was for the position: although from his very cradle he had been at the fringe of the theatre world because of his elder half-brother, Herbert Beerbohm Tree, one of London's foremost actor–managers, he himself had no great love for drama. He consoled himself with the thought that other callings, such as that of porter in the underground railway, were more uncomfortable and dispiriting than that of theatre critic: ‘Whenever I feel myself sinking under the stress of my labours, I shall say to myself, I am not a porter on the Underground Railway’ (Beerbohm, Around Theatres, 4). But in time he grew into an able, discerning, and demanding critic of the London theatre.

Max's personal life was peculiar. For a time in 1893 he had a sentimental crush on a happily unobtainable fifteen-year-old music-hall star, Cissie Loftus. In 1895 he became vaguely attached to Grace Connover, an actress in his brother's theatre company (Max nicknamed her Kilseen, for killing scenes on stage). The ‘engagement’ lingered for eight years before dying out. Next, in 1903, he became briefly engaged to another actress, Constance Collier, a successful, glamorous leading lady, again from his brother's theatre company; she broke off the engagement after a few months. In 1904 he met and became much taken with an American actress, Florence Kahn (d. 1951), the only daughter of a Jewish family from Memphis, Tennessee. By 1908 they were engaged. On 4 May 1910 Max and Florence were married at the Paddington register office; he quit his post at the Saturday Review, and went to live the rest of his life in the Villino Chiaro, a small house on the coast road overlooking the Mediterranean at Rapallo, Italy. Max and his wife seem to have had a thoroughly happy life together. There has been speculation that he was a non-active homosexual, that his marriage was never consummated, that he was a ‘natural celibate’ (Hall, Max Beerbohm: a Kind of Life, 120–21). The fact is, not much is known of Max's private life.

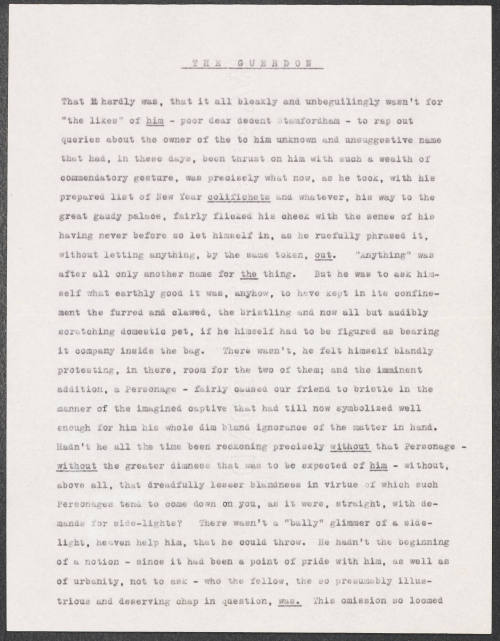

The writer

By the time Max had married, retired from London, and settled in Italy, his position as one of England's foremost essayists was firmly in place. As early as 1898 Shaw had, famously, pronounced Max ‘incomparable’ (G. B. Shaw, Our Theatres in the Nineties, 1931, 25.407). As a writer he had progressed towards a relaxed natural style. The early influence of Oscar Wilde on his prose, the constant paradoxes, the showiness, the over-cleverness had for the most part disappeared. By the turn of the century Max had found a surer, more distinctive voice, a prose distinguished by clarity and grace. The essays collected as Yet Again (1909) exemplified this style. But Max's writing attained even greater success with his next four books: in 1911 he published to great critical acclaim his only novel, Zuleika Dobson. This fantasy about the beautiful young woman whose visit to Oxford occasions the suicide of all the undergraduates has proved his most popular prose work; it has been the most continuously in print of all his books. An expanded edition, The Illustrated Zuleika Dobson, appeared in 1985. Zuleika Dobson was included in the 1998 controversial Modern Library list of ‘100 best novels’ of the twentieth century, ranking fifty-ninth (New York Times, 20 July 1998). In 1912 Max published a collection of seventeen parodies of contemporary writers, A Christmas Garland (new edn 1993), and again the critical reception was impressive: Filson Young, for example, writing in the Saturday Review, said: ‘He has not only parodied the style of his Authors, but their minds also’ (9 Nov 1912, 578–9); and the New York Times proclaimed: ‘Max has reached the Olympian heights of great satire’ (25 Jan 1913, 32). In 1919 he published Seven Men, his collection of short stories or ‘memories’, including ‘Enoch Soames’. (The title character, a decadent ‘Catholic Diabolist’ poet of the 1890s, sells his soul to the Devil in exchange for the privilege of visiting the British Museum reading room 100 years later, at which time he hoped to find that posterity had been kind to his reputation. His eagerly awaited ‘appearance’ on 3 June 1997 caused a stir in the London press.) In 1920 Max's last book of collected familiar essays, And even now, crowned his work in his favourite genre; it included such frequently anthologized titles as ‘No. 2 The Pines’ (on visiting Swinburne in the poet's old age), ‘Hosts and Guests’, ‘A Clergyman’ (on a minor figure in Boswell's Life of Samuel Johnson), and ‘Laughter’. Among the encomiums heaped upon him as essayist, Virginia Woolf's is representative: Max is the ‘prince of his profession’, someone who brought ‘personality’ into that genre for the first time since Montaigne and Charles Lamb (V. Woolf, The Common Reader, 1925, 216). Privately, she wrote to Max: ‘If you knew how I had pored over your essays—how they fill me with marvel—how I can't conceive what it would be like to write as you do!’ (Letters, 29 Jan 1928, 167).

The caricaturist

Max's reputation as a caricaturist was if anything higher than that as an essayist. In the late 1890s his drawing had also developed: it became more subtle, more intricate, more understated, the general softening of tone owing much to the addition of light colour washes, something Will Rothenstein had urged on him. Max himself remarked that as he got older (on into his late twenties) he found that his two arts—his ‘two dissimilar sisters’—were growing more like each other: his drawing had become ‘more delicate and artful ... losing something of its pristine boldness and savagery’, while his writing, ‘though it never will be bold or savage, is easier in style, less ornate, than it used to be’ (typescript, Merton College, Oxford). Max's was one of those rare talents equally distinguished in two arts. His sister arts sometimes come together in those of his drawings with more or less lengthy captions. A drawing, for example, of a clowning and self-satisfied G. B. Shaw bears the legend: ‘Magnetic, he has the power to infect almost everyone with the delight he takes in himself.’ Another, London in November and Mr Henry James in London, shows James, enveloped in a London fog, holding his hand up in front of his face; the legend, an adroit parody of the Master's style, reads:

It was, therefore, not without something of a shock that he, in this to him so very congenial atmosphere, now perceived that a vision of the hand which he had, at a venture, held up within an inch or so of his eyes was, with an almost awful clarity being adumbrated ...

Max once described caricature as ‘the delicious art of exaggerating, without fear or favour, the peculiarities of this or that human body, for the mere sake of exaggeration’ (Beerbohm, A Variety, 119). He admitted privately that he hoped also to get at the ‘soul’ of a man, but through the body:

When I draw a man, I am concerned simply and solely with the physical aspect of him ... [But] I see him in a peculiar way: I see all his salient points exaggerated (points of face, figure, port, gesture and vesture), and all his insignificant points proportionately diminished ... In the salient points a man's soul does reveal itself, more or less faintly ... It is ... when (and only when) my caricatures hit exactly the exteriors of their subjects that they open the interiors, too. (Letters, 35–6)

The perfect caricature, Max explained, must be

the exaggeration of the whole creature, from top to toe. ... The whole man must be melted down, as in a crucible, and then, as from the solution, be fashioned anew. He must emerge with not one particle of himself lost, yet with not a particle of himself as it was before. (Beerbohm, A Variety, 127–8)

Moreover, the caricaturist does not exaggerate this or that salient point deliberately: he ‘exaggerates instinctively, unconsciously’ (ibid., 124). Accordingly, Max believed that the caricaturist should never draw from the life because he would be ‘bound by the realities of it’ (ibid., 128). His own manner of operation was to stare at a person for a few moments and draw him later—that evening, or many evenings, or even years, later.

Max's first public showing had been at the Fine Art Society's exhibition in 1896, ‘A century and a half of English humorous art, from Hogarth to the present day’, to which he contributed six caricatures. His first one-man show was at the Carfax Gallery in 1901. By 1904, the year of his second published book of caricatures, The Poets' Corner, and of his second one-man exhibition at the Carfax Gallery, the Athenaeum was calling him ‘our one and only caricaturist’ (28 May 1904, 695). After two more Carfax exhibitions, in 1907 and 1908, Max contributed to four group shows at the New English Art Club, 1909–11. Thereafter, he exhibited his work exclusively at the Leicester Galleries, first in 1911. By the time of the second such show, in 1913, The Times confidently acclaimed Max ‘the greatest of English comic artists’ (12 April 1913, 6). Six more Leicester Galleries exhibitions followed during his lifetime, in 1921, 1923, 1925, 1928, 1945, and 1952. Almost the only complaint heard among the reviewers was the occasional one that he was not a draughtsman, but the objection was almost always followed by a retreat. One reviewer in 1913 said:

There is, of course, a negligible sense in which [Max] is no draughtsman. He does not, perhaps cannot, and probably does not care to make his figures stand on their feet, or sit in their chairs; yet he is a master of expressive line. (Edward Marsh, Blue Review, June 1913, 145)

In 1926 another reviewer wrote:

In terms of aesthetics Mr Beerbohm is not a draughtsman at all; he has a delicate sense of color, decorative felicity ... but he has never learned to draw ... For his own purposes, however, his drawing is consummate ... He has a genius for likenesses; better than anyone else he understands how to convey the attitudes of his subjects ... Add to these humor without venom and refined imagination and you have lifted caricature into the realm of art. (New York Herald Tribune, ‘Books’, 7 Feb 1926, 2)

In 1954 Edmund Wilson judged Max ‘the greatest caricaturist of the kind—that is, portrayer of personalities—in the history of art’ (Behrman, 262). This assertion, in regard to quantity, certainly, was to find support in the figures set forth in the 1972 Hart-Davis Catalogue of the Caricatures of Max Beerbohm: in more than 2000 formal caricatures the artist drew almost 800 ‘real people’.

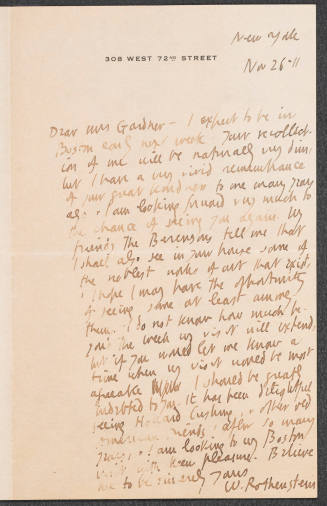

Many of the people Max drew he knew personally, and, with a few exceptions—Kipling for one—those he knew he liked, and they liked him. His subjects, or ‘targets’, included many well-known figures: Oscar Wilde, Thomas Hardy, Henry James, G. B. Shaw, W. B. Yeats, Joseph Conrad, Lytton Strachey, J. A. M. Whistler, Aubrey Beardsley, John Singer Sargent, Augustus John. A few of his subjects he never met: W. E. Gladstone, Benjamin Disraeli, Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and royalty, including Queen Victoria (Max seldom caricatured women, though he drew the queen at least nine times), Edward VII, George V, Edward VIII. Max also drew innumerable lawyers, musicians, financiers, professors, restaurateurs, sportsmen, newspaper magnates, dandies, tailors, industrialists, landowners. Hundreds of these individuals would be utterly forgotten today, had not Max ‘got’ them. It is noteworthy, too, that Max often caricatured himself. The Hart-Davis Catalogue lists ninety-seven self-caricatures, more entries than for any other subject, Edward VII and George Bernard Shaw being the closest, with seventy-two and sixty-two entries, respectively.

None the less, although most of Max's caricatures are of his contemporaries, he made two major ventures into the past, working from old portraits, drawings, and photographs. The result was some of his most enduring work, and the two most popular of his ten published books of caricatures, The Poets' Corner (1904) with subjects ranging from Dante and Shakespeare to Wordsworth and Coleridge and Tennyson and Browning; and Rossetti and his Circle (1922, new edn 1987), which offers such notables as A. C. Swinburne, John Ruskin, George Meredith, and William Morris in the company of Max's favourite nineteenth-century personality, the painter/poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Major collections of Max Beerbohm's caricatures are to be found in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; the Tate collection; the Victoria and Albert Museum; Charterhouse, Godalming; the Clark Library, University of California; and the Lilly Library, University of Indiana, Bloomington; depositories of both caricatures and archival material include Merton College Library, Oxford; the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin; the Robert H. Taylor collection, Princeton University Library; the Houghton Library, Harvard University; and the privately owned Mark Samuels Lasner collection.

Italian years

After 1910 Max lived contentedly in Rapallo, as a reclusive English gentleman (he never took the trouble to learn Italian). He returned to England only during the two world wars, and occasionally on personal business, chiefly to arrange exhibitions with the Leicester Galleries. Around 1930 he gave up caricaturing: ‘I found that my caricatures were becoming likenesses. I seem to have mislaid my gift for dispraise. Pity crept in. So I gave up caricaturing, except privately’ (Behrman, 140).

In 1935 Max began broadcasting for the BBC, reading essays, always as ‘an interesting link with the past’ (Beerbohm, Mainly on the Air, 34). He continued to make fourteen broadcasts in all, right through to the year of his death. Rebecca West said, ‘I felt ... that I was listening to the voice of the last civilized man on earth. Max's broadcasts justify the entire invention of broadcasting’ (Behrman, 265). But Max wanted no part of television. In 1955 the National Broadcasting Company in New York offered him considerable money to do a series of television talks. A representative of the company visited him in Rapallo:

You see, Sir Max, it will all be very simple. Our people will come and arrange everything. You will sit, if you like, where you are sitting now. You will simply say, ‘My dear friends, I am very happy to be here addressing you.’ Max replied, ‘Do you wish me to start with a lie?’ (Cecil, 491)

In 1939 George VI offered him a knighthood, and Max, who had so satirized the royal family, gratefully accepted. The irony of it pleased him. Always the dandy, he took special care with his dress. After the ceremony, he wrote to a friend,

My costume yesterday was quite all right ... Indeed, I was (or so I thought, as I looked around me) the best-dressed of the Knights, and quite on a level with the Grooms of the Chamber and other palace officials. I'm not sure that I wasn't as presentable as the King himself—very charming though he looked. (typescript, Merton College, Oxford)

In 1942 Max received an honorary degree from his alma mater, Oxford, and in 1945 his old college, Merton, made him an honorary fellow.

In many ways Max, in the latter part of his life, was out of step with the times; he remained a voice from the past. The works of D. H. Lawrence, for example, gave him little pleasure. Although willing to admit Lawrence's ‘unquestionable genius’, Max thought his prose style ‘slovenly’ and the man himself ‘afflicted with Messiahdom’ (Cecil, 483). When shown a copy of Joyce's Finnegans Wake shortly before being made Sir Max Beerbohm, he leafed through it and remarked, ‘I don't think he will get a knighthood for that!’ (ibid., 443). When Edward Marsh wrote to Max to ask if he would allow the Contemporary Art Society to commission Graham Sutherland to paint his portrait, Max declined, telling Marsh that although he had in his time been ‘a ruthless monstrifier of men’, he was, like the proverbial bully, a coward (Letters, 219). Privately, he told Samuel Behrman that in Sutherland's portrait of Somerset Maugham—which Marsh in his letter had held up as a masterpiece—‘Maugham looks ... as if he had died of torture’ (Behrman, 148–9). Max would have nothing to do with modern psychology or the theories of Freud: ‘I adored my father and mother and I adored my brothers and sisters. What kind of complex would they find me the victim of? ... They were a tense and peculiar family, the Oedipuses, weren't they?’ (Bacigalupo, 29).

After the death of Max's wife, Florence, in 1951, Elisabeth Jungmann, formerly the personal secretary of the German writer Gerhart Hauptmann, became Max's secretary and companion. On 20 April 1956 Max, from what was to be his deathbed, married her, to ensure that under Italian law she would inherit all his possessions. Max Beerbohm died at Rapallo on 20 May 1956. His body was cremated at Genoa, and the ashes taken to London, where they were interred in St Paul's Cathedral on 29 June.

N. John Hall

Sources

N. J. Hall, Max Beerbohm: a kind of life (2002) · D. Cecil, Max: a biography (1964) · S. N. Behrman, Portrait of Max: an intimate memoir of Sir Max Beerbohm (1960) · Letters of Max Beerbohm, 1892–1956, ed. R. Hart-Davis (1988) · Max Beerbohm's letters to Reggie Turner, ed. R. Hart-Davis (1965) · Max and Will: Max Beerbohm and William Rothenstein, their friendship and letters, 1893 to 1945, ed. M. Lago and K. Beckson (1975) · R. Hart-Davis, ed., A catalogue of the caricatures of Max Beerbohm (1972) · N. J. Hall, Max Beerbohm caricatures (1997) · The works of Max Beerbohm (1896) · M. Beerbohm, More (1899) · M. Beerbohm, Yet again (1909) · M. Beerbohm, And even now (1920) · M. Beerbohm, Mainly on the air (1957) · M. Beerbohm, Around theatres, new edn (1954) · M. Beerbohm, A variety of things (1928) · Siegfried Sassoon letters to Max Beerbohm: with a few answers, ed. R. Hart-Davis (1986) · W. Rothenstein, Men and memories: recollections of William Rothenstein, 1900–1922 (1932) · G. Bacigalupo, Ieri a Rapallo [1992], 29

Archives

AM Oxf. · Harvard U., Houghton L., corresp. and papers · Indiana University, Bloomington, Lilly Library, corresp. and drawings · Merton Oxf., corresp. and papers incl. literary MSS and drawings · NRA, priv. coll., corresp. and literary papers · Tate collection · U. Cal., Los Angeles, corresp. and literary papers · V&A · Yale U., Beinecke L., corresp. and literary MSS :: BL, corresp. with William Archer, Add. MS 45290 · BL, letters to Lydia and Walter Russell, RP2565 [copies] · BL, letters to George Bernard Shaw, Add. MS 50529 · Bodl. Oxf., corresp. with Sibyl Colefax · Bodl. Oxf., corresp. with Geoffrey Dawson · Bodl. Oxf., letters to the Lewis family and papers · CAC Cam., letters to Cecil Roberts · CUL, letters to Kathleen Bruce · CUL, letters to Lady Kennet · Harvard U., Houghton L., letters to Sir William Rothenstein · priv. coll., corresp. · Ransom HRC, corresp. with John Lane · TNA: PRO, letters to J. Ramsay Macdonald, 030/69 · U. Edin. L., letters, mainly to Alfred Wareing · U. Glas. L., letters to D. S. MacColl · U. Leeds, Brotherton L., letters to Edmund Gosse FILM

Ransom HRC SOUND

BL NSA, documentary recordings; performance recordings incl. the BBC broadcasts ‘Music halls of my youth’, ‘Nat Goodwin—and another’, ‘George Moore’, and ‘Hethway speaking’ · L. Cong., ‘First meetings with W. B. Yeats’, ‘London revisited’ · Sir Max Beerbohm reading his own works, Angel recording, no. 35206 [‘The crime’ and ‘London revisited’]

Likenesses

H. M. Beerbohm, caricature drawing, c.1893, Merton Oxf. · W. Rothenstein, lithograph, 1898, NPG · H. M. Beerbohm, caricature drawing, c.1900, AM Oxf. · J. E. Blanche, oils, 1903, AM Oxf. · W. Nicholson, oils, 1905, NPG [see illus.] · A. L. Coburn, photogravure, 1908, NPG · A. Rutherston, portrait, 1909, U. Texas · W. Rothenstein, pencil drawing, 1915, Man. City Gall. · F. Young, photograph, 1916, NPG · H. M. Beerbohm, watercolour caricature, 1923, NPG · E. Kapp, ink, charcoal, and wash drawing, 1923, Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham · W. Rothenstein, pencil drawing, 1928, NPG · R. G. Eves, oils, 1936, Tate collection · R. G. Eves, pencil drawing, 1936, NPG · K. Bell Reynall, bromide photographs, 1955, NPG · C. Beaton, photograph, NPG · H. M. Beerbohm, pen and wash caricature, U. Texas · K. Kennet, statuette, Merton Oxf. · W. Nicholson, drawing, NPG · W. Rothenstein, drawing, Merton Oxf. · C. H. Shannon, lithograph, NPG

Wealth at death

£9222 5s. 2d. in England: administration, 3 July 1957, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–16

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

N. John Hall, ‘Beerbohm, Sir Henry Maximilian [Max] (1872–1956)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/30672, accessed 5 Oct 2017]

Sir Henry Maximilian Beerbohm (1872–1956): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/30672

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Bradford, Yorkshire, 1872 - 1945, Far Oakridge

Brighton, 1872 - 1898, Menton, France

Crowthorne, 1862 - 1925, Cambridge, England

Speldhurst, England, 1864 - 1950, Zurich Switzerland

London, 1843 - 1932, Godalming, England

Surbiton, Surrey, 1863 - 1920, London