Gustav Mahler

Austrian, 1860 - 1911

Open in new tab

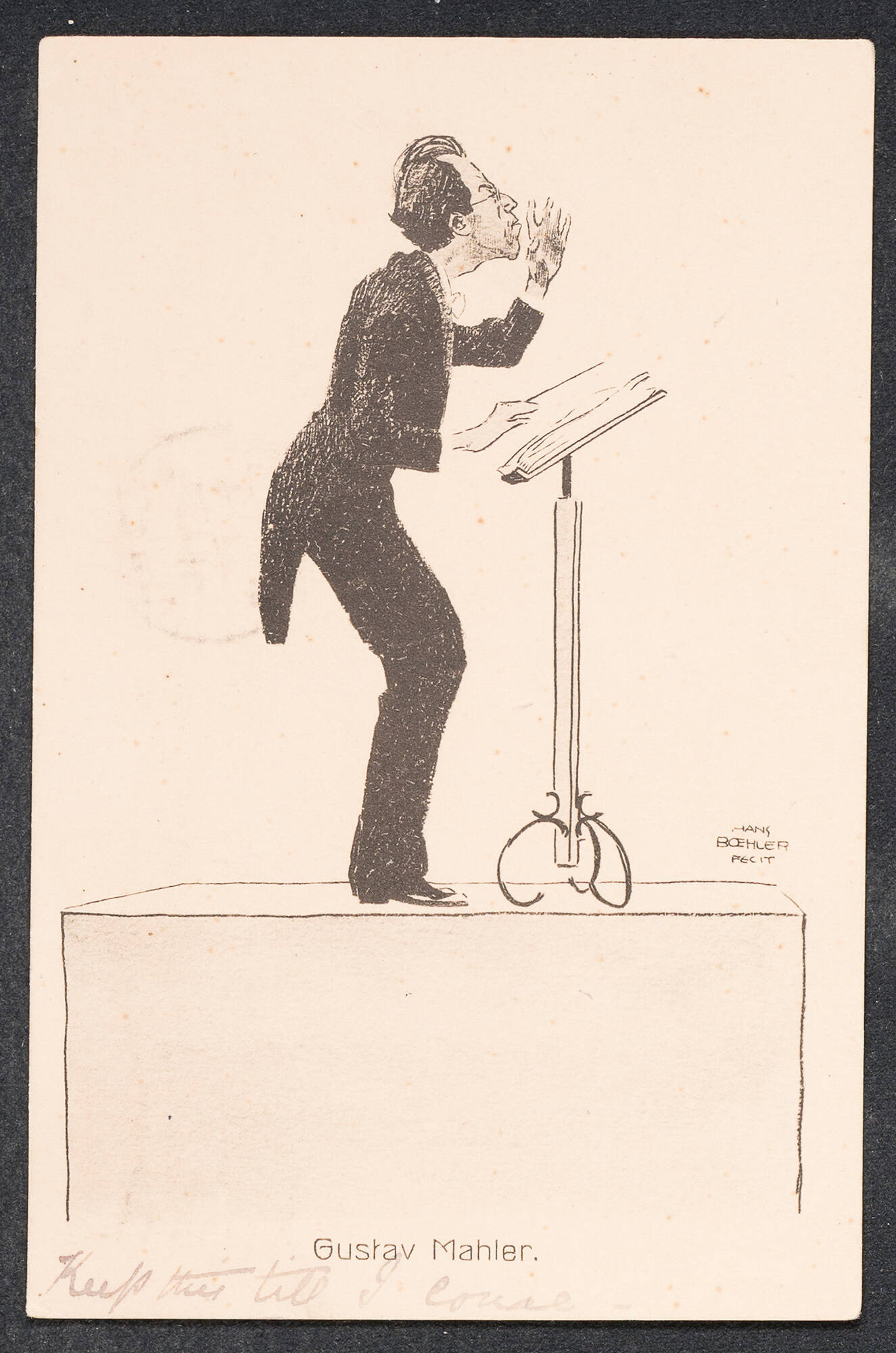

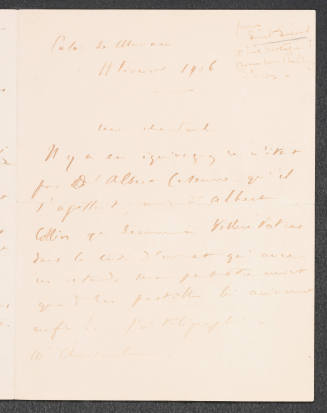

Gustav Mahler. Caricature by Hans Böhler.

Lebrecht Music & Arts

1. Background, childhood, education, 1860–80.

Mahler’s parents were members of the Habsburg empire's increasingly assimilated Jewish petit-bourgeoisie of the mid- and later 19th century. In the year of Emperor Franz Joseph's ‘mobility’ decree (1860), Marie, a soap-maker's daughter, and Bernhard Mahler, an aspiring tavern proprietor, moved across the Bohemian border into Moravia with their recently born son Gustav, the eldest of their six children (out of 14) to survive infancy. They joined a flourishing German-speaking Jewish community in Iglau, an attractive market town where Bernhard’s rougher side brought him into conflict with the local police, but where his determination and generally sound commercial sense enabled him to build up a secure distillery and tavern business. Subsequently characterized as an ill-tempered man who beat his children and behaved insensitively towards his more delicate wife, he nevertheless achieved a measure of respectability; his conventional aspirations for his family eventually permitted a proudly supportive attitude to his eldest son's musical inclinations.

Iglau was a thriving – culturally and linguistically German – centre of the cloth trade. The character of its busy musical life was variously derived from the folk traditions of the local Czech peasantry and itinerant Bohemian players, from German choral music (associated with the church of St Jakob), an amateur orchestra and a small professional theatre and opera house. The garrison stationed in the barracks supported a military band that participated in local festivals and gave regular concerts in the town's spacious square. Mahler's parents lived close to the square and throughout his childhood he was an enthusiastic observer at band concerts and parades. Family servants and Catholic school friends taught him songs of various kinds and players from the theatre orchestra gave him lessons. In keeping with the equating of social status with German culture typical of the period, Bernhard Mahler collected a small library and bought a piano, on which his son rapidly acquired sufficient expertise to be presented as a local Wunderkind by the age of ten. ‘High’ German musical culture was absorbed from scores borrowed from a subscription library and from teachers, including the musical director of St Jakob, Heinrich Fischer, who gave Mahler his first harmony lessons and whose son was one of his close friends.

Mahler's general education at the Iglau Gymnasium was interrupted in 1871 when his father sent him to the New Town Gymnasium in Prague, to improve upon his hitherto mediocre school results. The experience was an unhappy one and his father brought him back to Iglau. Formal musical training was considered only after Mahler's abilities had impressed the manager of a local estate, who subsequently made representations to the family. Bernhard Mahler eventually agreed to send his son for an audition with Julius Epstein in Vienna. Mahler was accepted as a student at the conservatory, beginning in the academic year 1875–6. Over the next three years he distinguished himself as a pianist (studying with Epstein) but turned to composition as his primary subject (studying harmony with Robert Fuchs and composition with Franz Krenn). His graduation submission was a scherzo for piano quintet, now lost.

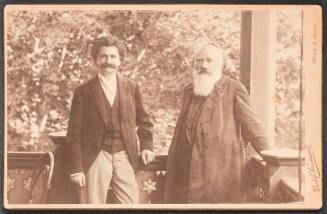

Mahler's formal musical training thus took place in the Vienna of Brahms and Hanslick, and he became a prominent member of a student generation newly inspired by Wagner. Like his friends Hugo Wolf, Hans Rott, Rudolf Krzyzanowski and Anton Krisper, he developed broad musical sympathies, although his lively interest in Wagner, and Wagner's unlikely Viennese advocate Anton Bruckner, marked him out as a supporter of the modernist tendency. This was scorned by many of his teachers at the conservatory, including its anti-Semitic director Joseph Hellmesberger. Mahler became acquainted with Bruckner, some of whose university lectures he attended (without formally becoming his pupil) and whose affection he inspired. At the composer's request, Mahler prepared, with Ferdinand Löwe, a piano-duet version of Bruckner's Third Symphony, which was published in 1880. While Mahler later conducted cut versions of Bruckner's symphonies, he continued to promote their wider dissemination.

It is one of the ironies of Viennese cultural politics in the 1870s that Mahler's awareness of anti-Semitism in the imperial capital probably helped confirm his Wagnerian sympathies at a time when Wagner's own anti-Semitic sentiments were being more forcefully publicized. After successfully graduating from the Iglau Gymnasium by passing the ‘matura’ (at the second attempt) in September 1877, Mahler was eligible to attend courses at Vienna University. Those for which he enrolled in 1877, 1878 and 1880 engaged him little, but genuine literary and philosophical interests drew him towards like-minded student members of the Academic Wagner Society (which he joined in 1877) and to the circle of the university-based ‘Leseverein der deutschen Studenten Wiens’, whose pan-Germanist members included the subsequently influential left-wing politicians Engelbert Pernerstorfer and Victor Adler (founder of the Austrian Social Democratic party); the young poet Siegfried Lipiner was a forceful proponent of the ideas of Nietzsche. Wagnerism, socialism, pan-Germanism and Nietzschean philosophy achieved an unlikely and intellectually explosive liaison in that circle, which Mahler and some of his friends from Iglau recreated in an enthusiastic discussion group of their own. In this context Mahler encountered some of his closest friends of later life and began to plan ambitious works, two of which failed to win him the valuable Beethoven Prize; on the second occasion (1881) he entered Das klagende Lied. The closing years of his student life in Vienna brought him his earliest conducting engagements and found him earning money from piano teaching, frequenting philosophical coffee houses and fostering a fashionable form of artistic Weltschmerz that fuelled idealistic socialist beliefs.

2. Early conducting career, 1880–83.

While anti-Habsburg feelings may have coloured his inherited sympathy with a wider German culture, Mahler's earliest conducting posts increased his familiarity with the territories of the Austro-Hungarian empire. The first (1880) was a summer job in a small wooden spa theatre at Bad Hall, to the south of Linz in Upper Austria. Its scant resources and unremitting programme of operetta provided little for which Mahler could thank his newly acquired agent apart from practical experience, which he proved adept at turning to his advantage (he had previously conducted only student rehearsals at the conservatory). In the following year he was engaged at the more professional and ambitious Landestheater in Laibach (now Ljubljana), whose troupe of singing actors staged both plays and operas in a modest 18th-century theatre. Here the 21-year-old Mahler conducted about 50 opera and operetta performances, including his first opera (Il trovatore, on 3 October 1881) and others by Rossini, Donizetti, Verdi, Mozart and Weber. His first significant press reviews in Laibach testify to the unifying role that music still had in an increasingly unstable empire; both German and Slovenian newspapers supported Mahler's efforts in a demonstration of cultural unanimity that became rarer in his later career.

Mahler's third appointment, occasioned by a suddenly vacated post, took him northwards from Vienna in January 1883 back to Olmütz (now Olomouc) in his native Moravia, where in September 1882 he had conducted a single performance (Suppé's Boccaccio) at the Stadttheater in Iglau. His loneliness and unhappiness in Olmütz were exacerbated by the news of Wagner's death in February 1883, but the practical skills he had acquired in Bad Hall and Laibach bore fruit in a judicious policy of focussing the mediocre company's strengths in practicable works, like Méhul's Joseph, rather than attempting the Mozart and Wagner it (and no doubt Mahler) would have preferred. He was in Olmütz for only three months before returning to a temporary post as chorus master at the Carltheater in Vienna, but it had been long enough to instil in the performers an apprehensive respect for his fiery and uncompromising manner. Its tangible results impressed a visiting producer from Dresden (Karl Ueberhorst) who helped arrange his release from the world of Austro-Hungarian second- and third-rate theatres. A trial week at the Königliche Schauspiele in Kassel, at the heart of the new German empire, helped Mahler to finance a trip to Bayreuth to hear Parsifal in July 1883 and led to his most important engagement thus far.

3. Kassel, 1883–5.

Mahler surreptitiously added two years to his actual age (23) when he signed his contract at Kassel (where he worked from August 1883 to April 1885); his achievements there, both as a conductor and as a composer, would not have discredited an older man. His youthful idealism nevertheless came into conflict with the kind of theatrical management structure with which, and against which, he was to work for the rest of his career. Although he acquired the title ‘Royal Musical and Choral Director’ in October 1883, he was subordinate to a resident Kapellmeister, Wilhelm Treiber, who had reason to fear the threat posed by Mahler. Both men were subordinate to the theatre's state-appointed general manager, or Intendant, the Prussian army officer Baron Adolf von und zu Gilsa, who ran the theatre on authoritarian lines (Mahler's name appeared in a punishment book for minor offences, such as walking noisily on the heels of his boots and making the women of the chorus laugh).

It was as the employee, later director, of state or court theatres that Mahler was to develop his self-contradictory persona as a dictatorial trainer of singers and orchestral players who nevertheless resisted and privately scorned external authority and officialdom. In Kassel his first professionally performed composition was an uncontentiously successful suite of incidental music to a series of tableaux vivants for a charity event, based on J.V. von Scheffel's popular narrative poem Der Trompeter von Säkkingen (one of its movements seems later to have been adapted as the eventually discarded ‘Blumine’ of the First Symphony). His most influential success in Kassel, however, was not in the theatre but as conductor of a local festival performance of Mendelssohn's St Paul in a large drill-hall, with nearly 500 performers (29 June 1885). The Kapellmeister, Treiber, had expected to conduct this concert with the Kassel theatre orchestra; its success, with an ad hoc ensemble that included an infantry band, in no way assisted Mahler's relations with his superiors.

An unhappy love affair with one of the sopranos at Kassel, Johanna Richter, inspired a series of six love-poems from which Mahler drew the four texts of his Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen cycle (1883–5). The ending of the affair must have inflamed his increasingly urgent desire to leave Kassel. His letter requesting some form of assistantship to the celebrated conductor Hans von Bülow, who visited Kassel with the Meiningen court orchestra in January 1884, had humiliatingly been returned to Baron von Gilsa. Two other job-seeking letters bore richer fruit. Max Staegemann, director of the Leipzig Opera, offered him a six-year contract, beginning in 1886, as a junior colleague of Arthur Nikisch. Then, providentially filling the gap between his departure from Kassel (July 1885) and the start of his Leipzig appointment, there came an invitation from the Wagner impresario Angelo Neumann, who had been engaged to rescue the declining Neues Deutsches Theater in Prague.

4. Prague, 1885–6, and Leipzig, 1886–8.

Mahler welcomed the Prague appointment (regretting his binding agreement with Staegemann in Leipzig); his return to a prominent theatre on what was virtually his home territory was not unproblematic, however. Personal tensions of an already familiar kind developed between Mahler and his older colleague Ludwig Slansky and with the generally forbearing but economically pragmatic Neumann. Wider cultural tensions underlay the German theatre's need of rescue at that time. In Laibach German culture had bridged ethnic and linguistic divisions, but in Prague Czechs far outnumbered Germans, the Czech language provision of the German theatre having been taken over by a flourishing Czech National Theatre. Its repertory featured works by Smetana, Dvořák and the Russians, and its high performance standards were matched by an overtly Czech nationalist agenda. Neumann succeeded in winning back some of the German theatre's lost audience, aided by Mahler's successes with Mozart's Don Giovanni (in the city of its première) and with Wagner (Das Rheingold and Die Walküre). These, like his high-profile concert of February 1886 featuring extracts from Götterdämmerung and Parsifal alongside Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, were strikingly contextualized by the nationalist cultural politics undermining imperial control.

Ill-health had prevented Mahler's mother from travelling to see him conduct in Prague, but he was able to spend time with his family in Iglau before returning northwards to take up his new post in the town of Wagner's birth in July 1886. The mid-19th-century Neues Stadttheater of Leipzig had a large auditorium, excellent singers and a first-class orchestra (the Leipzig Gewandhaus). Although the almost inevitable rivalry with the well-established Nikisch, five years Mahler's senior, caused an early crisis over the conductorship of a new Ring cycle, the latter's indisposition in January 1887 led to Mahler taking over both Die Walküre and Siegfried and achieving a success that won over the Leipzig public and critics. Continuing resentment on the part of the orchestra, devoted to Nikisch and its respected concert conductor Carl Reinecke, was inflamed by Mahler's unyielding manner and punishing rehearsal technique, but he retained the support and personal friendship of the director, Staegemann, and managed to establish a congenial working routine that allowed time for composition. Ironically, he achieved his first important success as a composer in Leipzig with the completion of another man's work: Weber's posthumously performed comic opera Die drei Pintos.

This project arose through Mahler's connection with the family of Carl von Weber, grandson of the composer and a resident of Leipzig. Mahler laboriously transcribed and then completed the unfinished sketches of Die drei Pintos, making additional use of minor works by Weber and a small amount of his own original composition based on Weber's thematic material (in particular the entr'acte preceding Act 2). The work aroused considerable interest, not least on the part of Richard Strauss, who looked at and was impressed by Mahler's material during a conducting trip he made to Leipzig in 1887 (the meeting was the first in a fruitful professional and personal relationship that lasted until Mahler's death). The reconstructed Die drei Pintos received its successful première in Leipzig, under Mahler's baton, in January 1888; Tchaikovsky was present in an audience that included many influential critics and impresarios. Disappointment over the somewhat cool response of Cosima Wagner to his Lohengrin in 1887 was thus effectively dispelled; future productions of Die drei Pintos promised financial returns (the work was taken up by various theatres) and brought Mahler’s name into prominence in the European musical press.

Work on Die drei Pintos had led to a complex romantic entanglement between Mahler and Carl von Weber's wife, Marion. Mahler's involvement with the family had developed into warm friendship, focussing at first on the couple's three children, in whose company he claimed (unconvincingly) to have discovered for the first time Arnim and Brentano's romantic collection of recreated German folk poetry, Des Knaben Wunderhorn. His earliest settings from it nevertheless date from this period. The relationship with Marion von Weber deepened; their planned elopement may have been a retrospective fantasy on Mahler's part, but the intensity of his feelings contributed to the inception and composition of his First Symphony and of the first movement of the Second Symphony, later entitled ‘Todtenfeier’. Neither work reached a final form or public performance at that time and Mahler's compositional gifts were still a matter of sceptical conjecture even for some of his closest acquaintances, although the Staegemann and Weber families both reacted with enthusiasm to his piano performances of the newly drafted First Symphony. In May 1888, however, Mahler concluded his appointment at Leipzig by resigning after a public altercation with the chief stage manager, Goldberg, with whom his relationship had long been tense.

In the absence of clear plans, he was happy to return to Prague that summer to prepare for a tour of Die drei Pintos with Cornelius's Der Barbier von Bagdad. At first the rehearsals went well and cordial relations were re-established with Angelo Neumann. Mahler nevertheless suffered a stinging humiliation when one of his characteristic outbursts at a rehearsal of Der Barbier led to an argument with Neumann, who summarily dismissed him. Absorption in composition in a local café almost caused him to miss an important meeting with the cellist David Popper, who was a professor at the Budapest Academy of Music. A Viennese friend of Mahler's, the increasingly influential musicologist Guido Adler, had enthusiastically described his character and abilities to Popper, who was canvassing ideas about candidates for the directorship of the Royal Hungarian Opera in Budapest, which urgently needed revitalization and reform. Some prominent conductors, including Felix Mottl, were considered, but Popper’s impressions of the 28-year-old Mahler confirmed Adler’s recommendation and were significant in the ensuing negotiations. These concluded with Mahler signing a contract that put him in artistic control of one of the major theatres of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

5. Budapest, 1888–91.

In Prague the politics of nationalism had provided a complicated backdrop to Mahler's role as official representative of German culture; in Budapest they were problematically internal to the institution he headed from October 1888. Hungary’s position in the dual monarchy led to irresolvable tensions between two forms of nationalist identity. Each had its proponents among the Magyar aristocrats who formed a significant part of the audience that supported opera in Budapest; for both groups nationalism entailed curbing desires for self-determination on the part of Hungary's internal ethnic minorities (Slovaks, Serbs, Croats and Slovenes). The more liberal Magyar nationalists, whose influence was increasing when Mahler arrived, sympathized with the formerly unifying German culture of Austria but required that librettos be translated into Hungarian and that native Hungarian singers fill as many roles as possible. The conservative faction favoured a more radical, anti-Austrian policy of cultural Magyarization, for example entailing the composition of ‘Hungarian’ operas by Hungarian composers.

Mahler's enforced Magyar sympathies were easily reconciled with his own artistic ideals where members of the liberal, German-orientated tendency were concerned. The significant Hungarian politician Count Albert Apponyi and the composer Ödön de Mihalovich, director of the Budapest Academy, were admirers of Wagner and became influential supporters of Mahler. So too did the State Secretary Ferenc von Beniczky, who was responsible for the management of the Budapest theatres and assumed the role of Intendant of the Royal Opera. The reason for the ascendancy of the liberals lay partly in the failure to maintain standards and audience levels on the part of the Erkel family, which had come to dominate the Royal Opera. Anti-Austrian nationalism was expressed in the historical and folklorist stage works of the aging composer Ferenc Erkel, whose sons Alexander (Sándor) and Gyula were employed as conductors at the opera house. Sándor Erkel had in fact been running it, as nominal director, in an increasingly negligent and unadventurous fashion. His continued presence, effectively demoted to a subordinate role as conductor, was to pose obvious problems to the incoming ‘Austrian’ director.

Mahler addressed the double task of increasing box-office returns while pursuing an effective Magyarization policy by concentrating initially on administration, planning and rehearsal. He took the conductor's stand himself for the first time in January 1889, in a half Ring cycle. Das Rheingold and Die Walküre, sung for the first time in Hungarian, were performed in the correct order, with no tickets available for individual operas; the audience was required to attend both or none. The demands of the liberal, Germanophile Magyars were thus satisfied in characteristically idealistic fashion. The critic Ludwig Karpath later recalled the electrifying effect of Mahler's innovations and performance style on the Royal Opera's partly philistine audience. Some of its members, particularly supporters of the Erkel brothers, resented the new director on anti-Semitic grounds and questioned the appropriateness of his relatively high salary. Other valuable accounts of Mahler's strategy and day-to-day life in Budapest (where he made efforts to learn Hungarian) were recorded by his Viennese friend, the historian and archaeologist Fritz Löhr and by a former conservatory acquaintance, the violinist and viola player Natalie Bauer-Lechner, who established a friendship with Mahler that was to last, with an increasing intensity of commitment on her part, until Mahler's marriage in 1902. Löhr, on his first visit to Budapest, observed Mahler's efforts to establish productive social relationships with influential members of Budapest society. Bauer-Lechner's observations from the end of Mahler's time in Budapest (autumn 1891) reflect his latterly embattled position in the city's cultural life, which helped to exacerbate minor opera-house disputes of the kind that he was always prone to generate. (On this occasion two singers, who considered themselves to have been dishonoured by his criticism, had publicly challenged Mahler to a duel; he declined.)

The intervening years were marked both by triumphs and by a series of personal and professional crises. Mahler's domestic circumstances and emotional life were profoundly affected in 1889 by family deaths. His father died in February; in the autumn the death of his married younger sister Leopoldine was followed by that of his long-ailing mother. By the end of the year Mahler had become head of a family comprising his two sisters, Emma and Justine, and his brothers Alois and Otto. Since Alois was doing military service, Mahler's primary concern was for his two sisters. After the sale of the Iglau house and Bernhard Mahler's business, he arranged for them to move in with Fritz Löhr and his wife in Vienna (Otto, now a student at the conservatory, was already lodging there). The elder of Mahler's sisters, Justine, stayed with him in Budapest for two extended periods during which their already affectionate relationship deepened into a mutually supportive friendship on which Mahler came increasingly to rely.

His stressful public life in Budapest disrupted the routine of spare-time composition that he had established in Leipzig. New projects seem not to have been significantly advanced between 1888 and 1891; however, music of the Leipzig period was presented there in the two earliest concerts in which works he considered important were performed in public. On 13 November 1889, shortly after his mother's death, Mahler included his songs Frühlingsmorgen, Erinnerung and Scheiden und Meiden (all subsequently published in the 1892 collection Lieder und gesänge) in a group he performed with the soprano Bianca Bianchi at a Budapest chamber concert. The local critics responded favourably to what they judged accomplished examples of German song. More momentous was the première of the first version of the First Symphony (presented as a five-movement ‘Symphonic Poem in two Parts’) a week later, on 20 November.

The symphony's reception was later represented by Mahler and his friends as a disaster which hindered the development of his reputation as a composer. Both operatic and wider cultural politics must in fact have influenced the Budapest audience's response to its performance under Mahler's baton in the middle of an otherwise conventional concert conducted by Sándor Erkel. Mahler and Erkel factions had expressed their feelings audibly in the hall, but the performance had clearly been of considerable power (Fritz Löhr testified to the impression made on both him and Mahler by the dress-rehearsal on 19 November, before an invited audience). The critics were most inventively nonplussed by the final two movements, in which the symphony's radical ‘new Romanticism’ seemed perplexingly and perversely expressed. What particularly hurt Mahler was a negative review by Viktor von Herzfeld, a Vienna Conservatory contemporary who had won (in 1884) the coveted Beethoven Prize that Mahler had twice failed to secure.

Following a Christmas spent with his brothers and sisters at the Löhrs’ house in Vienna, Mahler found his position at the Budapest Opera beginning to change in the early months of 1890. There had been a significant move to the nationalist-conservative right in Hungarian politics. The resignation in March of the Prime Minister Kalman Tisza and his replacement by Count Gyula Szapáry were the outward signs of a process that was clearly threatening to the Intendant, Beniczky. Mahler was meanwhile occupied with productions of Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots and Halévy's La Juive, along with further performances of Die Walküre (public opinion militated against his completion of a full Hungarian Ring cycle). His concern to respond pragmatically to the political situation in Budapest may be gauged from his care to mark the national celebration of the 400th anniversary of the death of King Matthias Corvinus with a gala concert featuring music by Ferenc Erkel, who shared some of the conducting with his son Sándor. The closing highlight of the 1889–90 season, however, was a new production of Mozart's Le nozze di Figaro with which Mahler delighted liberal supporters such as Count Apponyi.

The summer of 1890 began with a working Italian tour with his sister Justine, the purpose being to seek out promising future guest singers (Mahler had persistent difficulty in finding suitably trained Hungarians) and to assess the viability of some of the new Italian operas. Of the two such operas he staged in Budapest, Mascagni's Cavalleria rusticana was to prove influentially successful (the other was Franchetti's Asrael). The second half of the summer brought the Mahler and Löhr families together again in a rented villa in Hinterbrühl, where Mahler worked on Wunderhorn settings that later appeared in the second and third volumes of the Lieder und Gesänge (1892).

The 1891–2 season in Budapest opened against a background of mounting tension which led Mahler to begin negotiations with the director of the Hamburg Stadttheater, with a view to obtaining a post there. The decision proved timely. On 22 January 1891 Beniczky was replaced as Intendant by the nationalist Magyar aristocrat Count Géza Zichy. His agenda, supported by the conservative press and the new political climate, was clear: to remove from Mahler all executive power over artistic decisions. Zichy, a one-armed pianist with pretensions as a poet and composer, imposed his own artistic views with a determination that was coloured by anti-Semitic prejudice. Mahler's final triumph in Budapest was another Mozart opera, mounted before Zichy took over: a production of Don Giovanni in which he aimed for an unfashionable degree of ‘authenticity’ by restoring the original recitatives (long abandoned in favour of spoken dialogue), accompanying them himself on an upright piano in the orchestra pit. The production was received with unusual enthusiasm by Brahms, who was visiting Budapest. The satisfaction at winning the support of so influential a musician was deepened by the knowledge that it might open doors that would otherwise remain closed to him, particularly in Vienna; Mahler began to foster a respectful friendship with the older composer.

The end of Mahler's period at the Royal Hungarian Opera was marked by inevitable conflict between himself and Zichy, although he managed to show a degree of judicious forbearance once his contract with Hamburg was settled. He submitted his resignation in March 1891. An audience demonstration in his favour at a Lohengrin performance on 16 March (he was not conducting) must have given Mahler some satisfaction as he prepared to take up his new, if technically lower-status, position in Hamburg. (By a curious turn of events, his successor in Budapest was his former Leipzig rival Arthur Nikisch, whom Zichy honoured with a considerably higher salary.)

6. Hamburg, 1891–7.

Although Mahler planned at one stage to stay more or less permanently in Budapest, his affection for his native language, and hearing it sung, contributed to his pleasure at being back in Germany when he took up his post as chief conductor at the Hamburg Stadttheater in March 1891. His relations with the director Bernhard Pohl (known as Pollini) were often little less tense and stormy than those with Gilsa in Kassel or Zichy in Budapest; like the latter, Pollini retained overall executive power (although he may have tempted Mahler with the possibility of a directorship). However, he was not a court official but a modern impresario. Pollini's aim was to attract and maintain as large an audience as possible; in the Hanseatic free port of Hamburg economic viability was as important as the policing of an official public culture.

He was at first careful not to constrain Mahler, who rewarded Pollini's expectations by achieving resounding critical success with his initial appearances, conducting Siegfried and Tannhäuser. In April 1891 Mahler conducted Tristan und Isolde for the first time. His heavy conducting schedule militated against adequate rehearsal (of prime concern to the idealist in him) and led him that summer, unusually, to take advantage of Hamburg's access to the sea – the harbour area was one of his favourite afternoon walks – and make a solitary holiday trip to Copenhagen and Norway. That autumn Mahler worked hard to maintain high performance standards in both familiar repertory and new operas, for example Tchaikovsky's Yevgeny Onegin, whose German première impressed its composer. As always, Mahler's technique was to insist upon a concentrated rehearsal involvement that many singers and players found difficult to sustain. He inspired hatred and respect in almost equal measure; on one occasion a member of the opera staff had to summon the police to escort him home after a harassed flautist had gathered friends in the street with the intention of attacking Mahler.

The audience was fascinated by and largely supportive of his theatrical idealism, as a result of which Pollini was as happy to suffer the occasional outburst as he was to have him maintain the frequency of his appearances at the conductor's stand (at a time when publicity was not given to the name of the evening's staff conductor). Mahler's first Hamburg season ended with his taking the singers to participate in a six-week German opera season in London. This was organized by the English impresario Sir Augustus Harris, who devoted equal attention to opera and lavish Christmas pantomimes. Mahler conducted the first complete Ring cycles to be given in London, before joining his family for a holiday in Berchtesgaden. Fear of the serious cholera epidemic in Hamburg that summer caused him to delay returning to his post; Pollini angrily imposed a fine that signalled the end of their predominantly cordial relations.

Tensions between Mahler and his superiors were often productive, and he continued to achieve impressive results in the 1892–3 season. This did not prevent a deepening dissatisfaction with the unrelenting regime of repertory opera (in which a theatre offered a different production, from a currently-rehearsed group, on each night of the week). He famously denounced its ‘traditional’ style of performance as Schlamperei (‘slovenliness’). Mahler's increasing interest in the more idealistic world of the symphony concert at that time was closely linked to his longstanding admiration for Hans von Bülow, who was resident conductor of the Hamburg subscription concerts. Bülow had come to respect Mahler's style of conducting, particularly of Wagner, and a relationship between them developed. Bülow's celebrated eccentricities as a concert conductor began to include conversational asides to Mahler, whom Bülow seated close to his podium. Mahler became an unofficial deputy as Bülow's health declined and succeeded him after his death in 1894. Mahler met with little encouragement from Bülow, however, when he played the older man his Todtenfeier movement at the piano.

In 1893 Mahler established the standard pattern of his working summers for the rest of his life, returning to Austria – to Steinbach on the south-east shore of the Attersee in the Salzkammergut – and renting rooms for his family in a lakeside inn. They were joined there by Natalie Bauer-Lechner, who began systematically to compile the ‘Mahleriana’ diaries which later formed a significant posthumous source of information about his life and ideas during that period. (It was at Steinbach, in a one-room studio he had built by the lakeside in 1894, that he completed the Second and Third Symphonies in draft score, orchestrating them during the winter months in Hamburg.) In October 1893 Mahler conducted the second performance of his First Symphony, in Hamburg, in a revised version (still in five movements) as ‘Titan, a tone-poem in symphony form’, its individual movements also bearing descriptive titles. The concert included six of Mahler's Wunderhorn settings. Its location, the popular Ludwig Konzerthaus with its (expanded) resident orchestra, encouraged the scorn of some critics, although the audience's response was positive. Thanks to Richard Strauss, the symphony received a third and rather more influential performance the following year (3 June 1894) in Weimar at the annual festival of the Allgemeiner deutscher Musikverein.

The 1894–5 season proved to be a particularly significant one, not only with respect to Mahler's work at the Stadttheater, where he directed successful productions of Humperdinck's Hänsel und Gretel (which had been given its première the previous year by Strauss in Weimar), and Verdi's Falstaff. Hans von Bülow's death in February 1894 enabled Mahler to take over the Hamburg subscription concerts and provided him with a welcome opportunity to put his interpretative ideas more systematically to work in the concert hall. Bülow's memorial service in the city's Michaeliskirche (29 March 1894) also provided Mahler with long-sought inspiration for the still uncompleted finale of his Second Symphony. Klopstock's ‘Resurrection’ ode, sung during the service, supplied the opening lines of its choral text, the rest of which was written by Mahler himself; he completed the symphony that summer at Steinbach. Bruno Walter joined the Stadttheater as a somewhat awed junior conductor in 1894, soon becoming a valued ally and friend. Walter's recollections of Mahler at that time valuably complement those of others of his Hamburg friends, like the composer and critic Ferdinand Pfohl and the Czech composer Josef Bohuslav Foerster. The latter part of the season included personal tragedy for Mahler, whose brother Otto shot himself in February 1895. Increased concern for his two sisters led him to move them to Hamburg, where the three shared a home whose domestic arrangements were managed by his elder sister, Justine (a role she kept until both she and Mahler were married in 1902).

Family commitments added to Mahler's burdensome duties in Hamburg, where he had signed a new five-year contract in 1894. His extra work with the Philharmonic subscription concerts in 1894–5 was as stimulating as it was controversial; his editorial liberties with the scoring and tempos of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony caused a furore that contributed, along with financial losses during the season, to the decision not to re-engage him. Rumours about his possible departure from Hamburg were coloured by gossip about his affair with the soprano Anna von Mildenburg, who joined the opera company for the 1895–6 season (and to whom Mahler wrote about the first complete performance of his Second Symphony – at his own expense – in Berlin in December 1895). Elaborately prepared plans to leave Hamburg were realized soon after he completed his Third Symphony in the summer of 1896. Mahler's sights had long been set on returning to Vienna and he judiciously mobilized influential friends there, as well as in Budapest (which he visited during a conducting tour in March 1897 which took him to Russia for the first time). The sophisticated campaign was aimed at securing him the directorship of the Vienna Hofoper: a leading European theatre, served by a no less significant orchestra (the Vienna Philharmonic). Having removed the official barrier to the appointment of a Jew by converting to Roman Catholicism on 23 February 1897, Mahler began work as a Kapellmeister in Vienna in April 1897; by 8 September he had been promoted to director.

7. Vienna, 1897–1907.

Mahler characteristically saw his task at the Hofoper as a reforming one. Standards of performance and artistic direction had declined under his predecessor, the ailing Wilhelm Jahn, who had been happy to cater to the undemanding needs of a pleasure-loving Viennese audience. Of the Hofoper's other conductors only Hans Richter commanded wide respect. Mahler anticipated entrenched opposition in the imperial capital, divided politically between conservative, anti-Semitic supporters of its new Christian Socialist mayor, Karl Lueger, and those whose sympathies were with Victor Adler's left-wing Social Democratic party. His own position was further complicated by the theoretically mediating cultural role of the opera company as a court institution run by the emperor's chamberlain through his assistant, and eventual successor, Prince Alfred Montenuovo. Mahler's début for his ‘trial’ week was on 11 May 1897 with Lohengrin. The success of that performance, followed later in the month by a sparklingly restaged Zauberflöte, demonstrated Mahler's commitment to German culture (Wagner and Mozart were to remain central to his operatic repertory). His additional, more iconoclastic commitment to works outside the German tradition was shown by his first fully new production as director: Smetana’s Czech-nationalist opera Dalibor, staged, after consultation with the National Theatre in Prague, on the emperor's nameday (4 October 1897). Its significance must be interpreted in the light of the serious civil unrest over the repercussions of the ‘Badeni Ordinances’, which had recently granted equal official rights to the Czech language alongside German in Bohemia. Mahler's recomposed ending, leaving Dalibor triumphantly alive, might have been calculated to excite Czech nationalist feelings; a police presence in the theatre was accordingly arranged.

The cumulative effect of Mahler's perfectionism and daring at the Hofoper encouraged rapidly increased press and public interest whose economic effects impressed his superiors. Such interest was nevertheless to prove intrusive and damaging to Mahler himself. His insensitivity to the feelings of players and singers exacerbated the frequent scandals that were fostered by the more scurrilous and anti-Semitic members of Vienna’s close-knit but politically diverse press community. (The most personally distressing event of this period was the removal to an asylum of his friend Hugo Wolf, who in October 1897 began to suffer delusions brought on by tertiary syphilis.) His strategy developed in stages. His early years in Vienna were marked by a painstaking involvement with every aspect of production and management as he worked to build up a strong company of intelligent singers who were able to act convincingly. His treatment even of respected older singers and orchestral players was often peremptory. The result was a decade of opera in Vienna that was later recalled as an almost continuous festival of memorable productions, although the toll on Mahler’s mental and physical health was considerable. In the 1898–9 season Mahler took over from Hans Richter as conductor of the subscription concerts and thus added to his already heavy work-load. He accordingly took care to establish a congenial domestic environment and cherished the summer vacation months, which he saved for composition.

His life began gradually to settle into a less stressful pattern in the course of that season, which found him installed in a spacious modern apartment (in a new block on the Auenbruggergasse, designed by the leading modernist architect in Vienna, Otto Wagner). This he shared with his sister Justine, Emma having married the cellist Eduard Rosé, brother of the Vienna Philharmonic's leader Arnold Rosé, in August 1898. Mahler's three symphonies and the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen were in prospect of achieving wider recognition; all were now published or due to be published (partly thanks to a Bohemian grant arranged by Guido Adler in 1897). In April 1899 he conducted the Viennese première of his Second Symphony. Although over-work and ill health (particularly related to haemorrhoids) had contributed to the restriction of his compositional output to Wunderhorn settings since 1896, the summer of 1899, spent near Alt Aussee, brought a first draft of parts of the Fourth Symphony. This was completed in the summer of 1900 in a new composing studio, larger than the one at Steinbach, built in the pine forest above the southern shore of the Wörthersee in Carinthia, where Mahler had bought land on which to build a lakeside villa (completed in 1901).

His three seasons as conductor of the Philharmonic concerts in Vienna were no less controversial than the one in Hamburg. The hostility of some members of the orchestra was matched by that of many Viennese critics who were scornful of his theatrical gestures (frequently recorded and satirized in press cartoons and silhouette drawings) and his apparently disrespectful tendency to alter the scoring and heighten the effects of rhythmic and dynamic contrast in works by composers as revered as Schumann and Beethoven. His first season had included a version for full string orchestra of the latter's String Quartet in F minor (op.95) in a repertory featuring relatively new music by Humperdinck and Richard Strauss as well as a range of familiar Classical and Romantic works. The performance of his Second Symphony which ended the season on 9 April 1899 was not, however, integral to it but a separate charity event; even in his second season (1899–1900) Mahler included only a single group of four of his own orchestral songs. That season's highpoint was an ambitious trip to Paris with the orchestra to give five concerts in June as part of the World Exposition. On this visit Mahler first made the acquaintance of Colonel Georges Picquart and other supporters of Alfred Dreyfus, including Sophie Clemenceau (sister of his Viennese acquaintance Berta Szeps-Zuckerkandl), in whose house he met his future wife at a dinner party in November 1901.

By that time Mahler had resigned as conductor of the Philharmonic concerts, after a particularly stormy season in which he had included his reorchestrated version of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. Three weeks later (17 February 1901) he conducted the première of his own Das klagende Lied in its revised, two-part version. On 24 February a punishing afternoon concert, featuring Bruckner's Fifth Symphony, was followed by an evening performance of Die Zauberflöte. Haemorrhoids had once again been troubling him; during the night he suffered a serious loss of blood which necessitated emergency treatment, a subsequent operation and convalescence. That summer was the first in his new villa, near Maiernigg on the Wörthersee, where he was joined by Natalie Bauer-Lechner, his sister Justine and her future husband Arnold Rosé. By the end of it he had composed three of the Kindertotenlieder, four of the independent Rückert songs, Der Tamboursg'sell and part of the Fifth Symphony.

A new chapter in Mahler's life opened with his marriage to Alma Schindler on 9 March 1902, an event that excited Viennese gossip and shocked his closest friends, many of whom had learnt of his engagement only from newspaper reports. Some foresaw the problems that might attend Mahler's relationship with a woman almost 20 years younger than himself. Alma was the bright and attractive daughter of the Austrian landscape painter Emil Schindler; after his death her mother had married his former pupil Carl Moll, a prominent figure in the Modernist movement in Viennese art, closely associated with the Secession movement led by Gustav Klimt (one of Alma's many admirers). When she met Mahler, Alma was having an affair with her composition teacher Alexander Zemlinsky. Mahler had staged the première of Zemlinsky's opera Es war einmal at the Hofoper in 1900; Zemlinsky's friendship with Schoenberg enlarged the circle of younger modernist artists and musicians into which Alma introduced her husband. Mahler's musical contribution (a wind-band arrangement of part of the finale of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony) to the 14th exhibition of the Secession in 1902 – whose topic was derived from its focal sculpture: Max Klinger's Beethoven – brought him into contact with another Secessionist, Alfred Roller, whom he employed as an innovative designer at the Hofoper from 1903. Mahler's involvement with Vienna's musical modernists was closest in the 1904–5 season, during which he was elected honorary president of the Vereinigung Schaffender Tonkünstler: a concert-giving association, modelled on Klimt's Secession, which aimed to introduce the Viennese concert audience to a wide range of new music. Zemlinsky and Schoenberg, along with the latter's new pupils (from 1904) Anton Webern and Alban Berg, were central figures in this short-lived venture which nevertheless provided a model for later associations devoted to the promotion of new music.

Typical for her generation, Alma's attitude towards Mahler's music was initially ambivalent; her sceptical response to the Fourth Symphony (which was given its first performance in Vienna on 12 January 1902) was no doubt painfully focussed by Mahler's insistence that their marriage was conditional upon her renouncing her own ambitions as a composer. She later interpreted that ultimatum as a key to the problems that soon beset their relationship, particularly during the summer months in the Wörthersee villa. During the morning she was expected to be the unobtrusive housewife, looking after their daughters (Maria, born 3 November 1902, and Anna, born 15 June 1904) while Mahler composed in his forest studio. At first he clearly profited both mentally and creatively from the marriage. The conducting trip to Russia which had doubled as a honeymoon in March 1902 (they had left Vienna too soon to be able to attend the wedding of Justine and Arnold Rosé on the day after their own) was the first of a series of such absences from Vienna. These were increasingly to involve performances of his own music and signified a gradual change in Mahler's interpretation of his role at the Hofoper during the last five years of his directorship (1903–7).

While he retained a close interest in all productions and worked hard to maintain and strengthen the company he had built up, Mahler began to appear at the conductor’s stand less frequently and relinquished much of the day-to-day work to staff conductors like Franz Schalk and Bruno Walter (who had followed Mahler to Vienna in 1901). Certain new productions he took particular interest in, however, supervising the rehearsals and conducting at least the opening night. These included some of the relatively few new operas staged during his time at the Hofoper (like Strauss's Feuersnot in January 1902, Charpentier's Louise in March 1903 and Pfitzner's Die Rose vom Liebesgarten in April 1905). Mahler's relatively conservative repertory was to some extent dictated by the imperial censors, who resisted his efforts to stage Strauss's Salome in the 1905–6 season, finding its blasphemous implications and immoral subject matter inappropriate for a court theatre (the opera was in fact staged in Vienna, at the Deutsches Volkstheater, in 1907). The most consummate and innovatory productions of the Mahler era were those staged with Roller's symbolist-inspired and unusually lit sets from 1903: particularly Tristan und Isolde (21 February 1903) Don Giovanni (21 December 1905), Die Walküre (4 February 1907) and Gluck's Iphigénie en Aulide (18 March 1907). The Gluck was Mahler's last new production at the Hofoper.

Absences from Vienna to conduct his own works became more frequent after the highly successful première of the complete Third Symphony at the Allgemeiner Deutscher Musikverein festival in Krefeld on 9 June 1902. The Second and Third Symphonies gained increasing critical and popular acclaim. The first of many guest appearances as conductor of the Third Symphony took place in Amsterdam (October 1903), where Mahler forged a close link with the Concertgebouw Orchestra and its conductor Willem Mengelberg (whose devotion to his music was demonstrated in the Amsterdam Mahler festival of 1920, which greatly contributed to the composer's growing posthumous reputation). Mahler premières became significant and eagerly awaited events. The Fifth Symphony was first performed in Cologne in October 1904, the Sixth in Essen in May 1906 and the Seventh in Prague in September 1908. The last of his premières Mahler lived to conduct was that of the Eighth Symphony (two performances) in Munich in September 1910, attended by a large audience that included many influential European musicians and writers.

8. Europe and New York, 1907–11.

In the 1906–7 season, Mahler's conducting trips had begun to anger Prince Montenuovo and encouraged a dangerous escalation in the opera-house scandals (often involving disgruntled singers) which the anti-Semitic press, in particular, was ready to exploit. He had already signed a contract with Heinrich Conried, director of the Metropolitan Opera House in New York, before personal tragedy struck in the summer of 1907. After Mahler's return with Alma from a conducting engagement in Rome, their two daughters (who had stayed behind with their English governess) both succumbed to illness. Anna soon recovered, but Maria died from a combination of scarlet fever and diphtheria on 12 July 1907. Alma and her mother both needed medical attention after the removal of Maria's body from the Wörthersee villa. Mahler, after a routine examination by the doctor attending them, learnt that his own heart was in poor order. A Viennese specialist subsequently confirmed a valvular defect and recommended a programme of exercise that drastically curtailed Mahler's habitual enthusiastic walking, swimming and cycling.

After a final staging of Fidelio in Vienna on 15 October 1907 and a farewell performance of his Second Symphony in the Musikvereinsaal in November, Mahler departed for the USA, with Alma, as one of many high-profile European artists who were being invited to add lustre to the cultural life of New York. The considerable financial rewards were outweighed, in Mahler's case, by the socially élitist and aesthetically conservative style of the Metropolitan Opera, where Wagner was still performed with the cuts that had long been restored in Vienna. He was nevertheless impressed by the musicians he found there and sensed potential for improvement and change. His soloists were of world class (they included Caruso and Chaliapin) and while grief over Maria's death shadowed him, Mahler had a successful and rewarding season there, making his début with Tristan und Isolde (1 January 1908). His repertory was once again dominated by Wagner (Die Walküre and Siegfried) and Mozart (Le nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni), although he also conducted Fidelio with sets recreated from Roller's Vienna designs.

In May 1908, setting the pattern for the remaining years of his life, Mahler returned with Alma to Europe, where conducting engagements (including the première of his Seventh Symphony in Prague on 19 September) were fitted around a summer vacation devoted largely to composition. The Wörthersee villa had been sold (the events of the previous summer made it unbearable) and a new summer apartment rented in the Tyrol, in the ancient farmhouse of Alt-Schluderbach. This was not far from Toblach (now Dobbiaco) and the Landro valley, which had long been Mahler's favourite access point for the Dolomites. The last of his composing studios was an easily reached wooden summer-house at the edge of a pine forest. The new work he drafted that summer was Das Lied von der Erde.

Mahler’s second New York season began with a contract for a month of orchestral conducting. He was to direct the New York Symphony Orchestra in three concerts, the second of which (8 December 1908) was the American première of his Second Symphony. His return to the Metropolitan Opera on 23 December, with Tristan und Isolde, was somewhat embattled, because Conried’s successor as director, Giulio Gatti-Casazza, had imported Toscanini as a rival attraction to Mahler. Toscanini had insisted on conducting Tristan, but Mahler's protestations were heeded (he also conducted a series of performances of The Bartered Bride and a revival of Figaro). The season concluded with more concert conducting, this time with a specially reconstituted New York Philharmonic Orchestra, which he was to take over as principal conductor in the following season (the first in which he managed largely to escape from the opera house and devote himself to the more congenial task of orchestral conducting). This he began in October 1909 after a summer in which he drafted much of the Ninth Symphony before making a conducting trip to the Netherlands.

The New York Philharmonic season of 1909–10 gave Mahler much pleasure. His ambitiously eclectic choice of programmes (including modern works by Richard Strauss, Pfitzner and Rachmaninoff) inspired conflicting reviews; his licence with Beethoven received the usual condemnation, not least from émigré German critics, as did his performance of his own First Symphony (16 December 1909). The busy season concluded with an American tour with the orchestra before he returned to conducting engagements in Europe (the Second Symphony in Paris and concerts in Rome). That vacation, during which he sketched most of the Tenth Symphony, was marked by both triumph and catastrophe: triumph with the Eighth Symphony's first performances (Munich, 12 and 13 September), catastrophe in the form of his discovery that Alma had begun an affair with the young Walter Gropius while taking a cure at Tobelbad. Gropius followed her to Toblach, where Mahler pressed Alma to decide between them. Ostensibly committing herself to remain with Mahler, she secretly arranged to continue the relationship with Gropius (who later became her second husband). She admitted in her memoirs that both she and Mahler knew that their marriage had become a ‘lie’. The period immediately before the première of the Eighth Symphony, which Mahler now dedicated to Alma, was marked by both reawakened love for her and despairing self-castigation which led him to seek the advice of Sigmund Freud in Leiden (although brief and informal, their meeting seems to have afforded Mahler therapeutic insight).

Annotations in the manuscript sketches of the Tenth Symphony bear witness to the intense distress that underlay the outward stability which Mahler and Alma had regained by the time they returned to the USA for the 1910–11 season. Mahler's concert programming became even more adventurous, including works by such composers as Debussy, Elgar and MacDowell. Developing tension in his relations with the orchestra and its financial backers was overshadowed by what at first seemed a fatigue-induced illness in February 1911. It shortly became apparent to his doctors that Mahler had contracted bacterial endocarditis, from which there was little hope of recovery. The complex stages of his return, via a clinic in Paris, to Vienna, where he died on 18 May, were managed by Alma with relatively little direct assistance and increasing interest from the press. He was buried in the Grinzing cemetery on 22 May 1911.

9. Musical style.

Mahler's impulse towards assimilation into German culture prompted a lively ambition to master the repertory and techniques of the classical music which helped to shape his experience and aspirations. That ambition was also fired by the idealist aesthetics of Romanticism which positioned Austro-German classical music as ‘higher’ than other types in possessing spiritual and philosophical significance which transcended or even reconciled social and racial difference. Some of Mahler's earliest recollections, recounted to Natalie Bauer-Lechner, indicate that he began at an early age to interpret his musical performances for his family as symbolic dramas or narratives about people and social justice. He claimed, for example, to have invented a story for Beethoven's Variations op.121a on Wenzel Müller's Ich bin der Schneider Kakadu; the events of the tailor's life ended with a parody funeral march whose moral (Mahler decided) was: ‘Now this poor beggar is the same as any king!’ Mahler's later, implicitly less egalitarian ideas about musical signification, were revealed in something he appears to have told Freud, in 1910, about his youthful memory of an angry scene between his parents; he had fled, only to encounter a barrel organ in the street playing the popular song Ach, du lieber Augustin. He believed this experience had impaired his ability to disentangle ‘high tragedy’ from ‘light amusement’ in his music. His major works both articulate and seek to resolve the cultural tensions mapped by such stories.

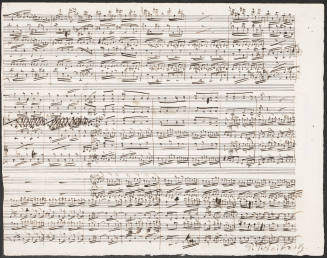

The stylistic and generic plurality of ‘voices’ in his symphonies has been prized as a function of their subversively modernist, even postmodernist, character. That it struck Mahler as problematic illuminates the propensity for parody or irony, often explicitly indicated in directions in the score, which contributes to their authenticity as cultural documents, resounding the very contradictions that Mahler's own inherited aesthetic ideals required to be resolved or transcended. The disruptive effect attributed by his culture to unabsorbed ethnic or popular influences in serious music is focussed in the family story of a visit to the synagogue during which the infant Mahler had shouted his disapproval at the solemn singing, intervening with a spirited rendering of the ribald Moravian-Czech street-song At' se pinkel házi (‘Let the knapsack rock’). His subsequent concern about the conflicting appropriateness of ‘high’ and ‘low’ musical styles was inevitably resolved more successfully in conceptual narrative than in supposedly purely musical terms, although his works’ complex and innovatory internal features have begun to inspire systematic analytical investigation. Mahler's descriptive interpretations of his music deserve to be reckoned as integral to its identity as a rhetorical discourse that was both constructing and keeping separate the complementary worlds of private experience and the public ceremonial which channelled and normalized it. Mahler's public pronouncements, from around 1900, denigrating the value and integrity of descriptive programmes require judicious cultural-historical interpretation and must not be accorded disproportionate authority; he no less frequently indicated that music was, for him, a higher form of philosophizing. To accept, with Theodor Adorno, that Mahler's works incorporate a critique of the cultural assumptions upon which they rely is to find significance in their many unusual features which fall outside the boundaries of more conventional musical concerns such as tonal argument and structural modelling. A list of such features might utilize the following categories: timbre, orchestration and the employment of extreme volume levels; the disposition of instrumental forces in space; the treatment of genre; detailed performance-related score directions (occasionally indicating parodistic or ironic intent); handwritten annotations in his manuscript scores; the symbolic or allegorical representation in music of gendered subjects, forces of nature or fate and group identity; and allusions to identifiable forms of ethnic or urban popular music (particularly dance forms like the ländler and the waltz).

10. ‘Das klagende Lied’, early songs, First Symphony.

The relatively small number of Mahler's surviving compositions, coupled with the assured personal style of the earliest of them, has given rise to speculation about lost or destroyed works from his student years. Surviving records and recollections have encouraged attempts to compile a list of such works, which seem to have included an overture (Die Argonauten) and a number of chamber works with piano. A single authenticated Piano Quartet movement (possibly from 1876) has survived: this purposeful sonata structure in A minor demonstrates sympathetic knowledge of Schubert, Schumann and Brahms. Of Mahler's two early operatic projects, Herzog Ernst vom Schwaben and Rübezahl, only the libretto of the latter survives, although music drafted for it appears to have originated in or been incorporated into at least one early song and parts of Das klagende Lied. A Symphonisches Praeludium discovered in the 1970s, in a piano transcription apparently copied by Mahler's friend Rudolf Krzyzanowski, is probably by Krzyzanowski himself or another of Mahler's student circle; Hans Rott's remarkable Symphony in E (which Mahler admired and quoted from, after Rott's death, in his own Second and Third Symphonies) similarly testifies to the manner in which their enthusiasm for Wagner and Bruckner must have informed the style and aims of all three.

With the exception of the Piano Quartet movement, all Mahler's earliest surviving works link poetic representation with musical aims. As well as texts for himself to set (e.g. Das klagende Lied, Rübezahl), Mahler wrote effective lyric poetry throughout his life. Goethe, Hölderlin and later Rückert are among his obvious models, although the stylized manner of the authentic but artfully refashioned ‘Old German songs’ of Arnim and Brentano's Des Knaben Wunderhorn anthology (1805–8) is evident in Mahler's lyrics long before he claimed to have discovered it around 1887. The writing, and setting, of such poetry played a part in Mahler’s efforts to create an identifiably ‘German’ voice. Surviving songs from 1880 (Im Lenz, Winterlied and Maitanz im Grünen) anticipate the more concentrated attempt of the three volumes of Lieder und Gesänge (published in 1892) to contribute to the tradition of the German piano-accompanied song.

While the term ‘Gesang’ was already signifying a more artful and expressively naturalistic lyric form, requiring a through-composed and less regularly periodic folksong style to that of the lied (e.g. Erinnerung in volume i of the Lieder und Gesänge), the dominant manner of Mahler's songs is defined by a rhetoric of arch naivety, masking considerable complexity of musical detail and symbolic meaning. The youthfully loving subject in close rapport with an anthropomorphized Nature (Frühlingsmorgen, Ich ging mit Lust durch einen grünen Wald) characteristically signifies an idyllic or utopian realm of existence, the disillusioning loss of which may be suggested by music whose diatonic clarity is subject to minor-key inflections and enigmatic forms of closure. Even an ostensibly uncomplicated Wunderhorn setting like Um schlimme Kinder artig zu machen (Lieder und Gesänge, ii) proves on closer inspection to involve the rejection of an amorous invitation; its verbal pretext – the woman's unseen and perhaps merely figurative children – is dutifully maintained by music that demands to be read as if between quotation marks.

Dance forms, serenades, children's songs, military signals and marches contribute to a complex vocabulary of signification in these songs, where stylistic and generic allusion is usually employed in preference to the establishment of a clearly defined and expressively engaged authorial voice (although Mahler subsequently proved familiar with the techniques appropriate in the period, derived from the slow movements of late Beethoven and the chromatic ‘prose’ style of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde). A similar, if still more elaborately complex rhetoric is deployed in the longest surviving example of Mahler's work from the period around 1880, the cantata Das klagende Lied, much of whose first version (completed in November 1880) predates any of the surviving music so far mentioned, with the exception of the Piano Quartet movement. This long-undervalued narrative piece was originally in three parts (the first was dropped in the revised version in which the work was first performed in 1901); its tale of two brothers who search for a flower that will win the hand of a ‘proud queen’ derives from the world of the Romantic fairy tale, specifically ‘The Singing Bone’ from the Kinder- und Hausmärchen of J.L. and W.C. Grimm. Mahler's setting of his own verse text (mostly in six-line stanzas with an ABABCC rhyme scheme) represents a remarkable achievement; its rejection in September 1883 by Liszt, to whom it had been sent for consideration for performance at an Allgemeiner deutscher Musikverein festival, must have been especially disappointing.

Deploying a large orchestra, chorus, two boy singers (in the first version) and four adult soloists, Das klagende Lied selectively treats scenes of dramatic action in a rich and multi-faceted narrative that involves stylized authorial intervention and apostrophe, interpolations by a kind of Greek chorus (in a style often evoking that of a Bach chorale) and the complicated conceit, derived from the original tale, whereby even the tragic climax of the work is precipitated by a musically articulated story-within-a-story. The boy who had found the flower was murdered by his evil brother (Part 1, Waldmärchen); one of the dead boy's bones is later discovered by a minstrel, who fashions a flute from it (Part 2, Der Spielmann); when he plays the flute at the wedding of the queen and the surviving brother, it sings in the voice of the latter's victim (Part 3, Hochzeitsstück). The murdered brother's song of lamentation (‘klagende Lied’) thus intervenes catastrophically in the celebrations, in a passage whose operatic and melodramatic qualities are made all the more telling by Mahler's first experimental use of offstage music (a wind and percussion band). Ostensibly evoking distant festivities, the effect of a military band playing outside the auditorium, oblivious to and even in direct conflict with the emotions and musical discourse of the onstage characters, seems to have been designed to turn the whole performance into an enacted parable of the double intervention by music in a scene of musically evoked power. The conclusion of Das klagende Lied is appropriately desolate: a sparse threnody evoking the deserted hall whose lights are extinguished as the castle ramparts crumble.

The ambivalence about meaning informing the early songs was here carried to daring heights. One of the public functions of music in Mahler's culture was to adorn the power of the state and support its official ideology; the suspicion that his works contained a moral or even political threat informed much of the negative criticism that greeted its rare performances, up to and including the première in Vienna (1901) of Das klagende Lied. Many features of his first three symphonies tend to justify that suspicion, although the formative work from which the First Symphony grew, the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (1883–5), was a more intimate essay in the cultural negotiation of personal emotion occasioned by the Kassel love-affair with Johanna Richter, to whom Mahler dedicated six poems from which the song cycle's four texts were chosen.

The fact that the first of these owes something to a poem from Des Knaben Wunderhorn nevertheless serves as a warning against simplistic readings of the cycle as autobiographical. Mahler carefully avoided references to locations or objects foreign to the world of the German Romantic lyric, where fields, woods and roadside lime trees provided a setting for the emotional dramas of simple souls whose only possessions might be feelings of love and loss. The wayfarer of the cycle is a standard cultural type whose musical voice is a mosaic of musical manners, sharply characterized and artfully deployed. Only in this respect does the cycle demonstrate features subversive of the cultural norms it otherwise adopts. Particularly in the final orchestral version of what was originally written for voice and piano, the insistent contrast between the opening song's lamenting phrase Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht (‘When my love gets married’) and its dance-like instrumental diminution suggests a more specifically Bohemian or Moravian folkdance than Romantic idealism would normally have favoured; the unusual tonal design of individual songs (the second moves from D major to F♯ major, the third from D minor to E♭ minor, the fourth from E minor to F minor) even signals the expressive authenticity and licence of nascent Modernism. Conventional and unconventional elements in the cycle are united in structural schemes that juxtapose irresolvably contrasting states and worlds of feeling. The second song, Ging heut' morgens übers Feld, evokes an idyllic realm of flowers and talking birds whose illusory reality is threatened in the question and answer of its postludial aside: ‘Will my happiness really begin now? No! The kind I mean can never blossom in me!’ Appropriately, the final song's resolution of the contradiction between ‘love and sorrow / world and dream’ insists upon the tread of a funeral march that turns F major into F minor.

The direct quotation of the F major music in the third movement of the First Symphony (marked ‘wie eine Volksweise’ – ‘like a folksong’) betrays Mahler's desire to naturalize his musical wayfarer and introduces the elaborate relationship that exists between the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen and the symphony, whose two parts draw on the cycle's juxtaposition of nature idyll and the troubled reality of subjective experience. The link between the two works is emphasized by the fact that most of the material of the exposition of the symphony's first movement (following the slow introduction) is derived from the cycle's second song. The tension between conformist assimilation and transgressive innovation, evident in Mahler's indecision about how to describe and title the symphony, was reflected in the different techniques and musical manners employed in its two parts (represented in the published version by movements 1 and 2 and movements 3 and 4 respectively). At its first performance, in Budapest (when the first part also included the later-discarded ‘Blumine’ movement between the other two), the pastoral-idyllic Part 1 was in general better received than Part 2, with its ‘new romantic’ excesses. At that time the work's modernity was additionally signalled by its being presented as a symphonic poem. Mahler's decision not to publish an explanatory programme nevertheless emphasized his contradictory ideas about how he wanted the work to be understood. For its second performance, in Hamburg, he retitled it and added an elaborately literary programme (compiled with the help of his friend in Hamburg, Ferdinand Pfohl). It alludes to at least two novels by Jean Paul (Titan and the Siebenkäs), E.T.A. Hoffmann's Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier and the illustration for a children's book mentioned in connection with the third movement; the title of the finale (See v below) seems to refer to Dante:

Part 1

Titan, a tone poem in symphony form

‘From the days of youth’, Flower-, Fruit- and Thorn-pieces

i. ‘Spring and no end’ (Introduction and Allegro Comodo). The Introduction depicts the awakening of Nature from the long sleep of winter.ii. ‘Blumine’ (Andante)iii. ‘With full sails’ (Scherzo)

Part 2

iv. Stranded! (A funeral march in ‘the manner of Callot’.) The following might explain this movement: the external inspiration for the piece came to the author from a parodistic picture well known to all children in Austria: ‘The Huntsman's Funeral’, from an old children's book: the animals of the forest accompany the dead huntsman's bier to the grave; hares escort the little troop, in front of them marches a group of Bohemian musicians, accompanied by playing cats, toads, crows etc. Stags, deer, foxes and other four-legged and feathered animals follow the procession in comic attitudes. In this passage the piece is intended to have now an ironically merry, now a mysteriously brooding mood, onto which immediately:v. ‘D’all Inferno’ (Allegro furioso) follows, like the suddenly erupting cry of a heart wounded to its depths.

The four-movement version in which the symphony is now known remains rich in imagery and technical diversity. In the opening bars Mahler uses the extraordinary orchestral effect of a unison A over seven octaves in the strings, all except the lowest basses playing harmonics, ‘Wie ein Naturlaut’ (‘Like a sound of nature’); a kind of virtual-reality effect is created by three offstage trumpets (the first two directed to be placed initially ‘in the very far distance’), as if to stress a physical separation between the platform orchestra as Nature, with its expicitly marked cuckoo calls, and the realm of human activity. Mahler characteristically consigned to the silence between the second and third movements the disillusioning dramatic catastrophe, figured as the tragic love experience which separates the symphony's protagonist, like the wayfarer of the song cycle, from the comforts of youthful illusion. What follows is the most experimental of the symphony's four movements: an ironic funeral march based on the children's round Bruder Martin (‘Frère Jacques’), whose trio-like interpolations include one of Mahler's most explicit evocations of the Bohemian street musicians encountered in his childhood; the pungent, chromatically inflected orchestral timbre is appropriately enriched (at a point marked ‘Mit Parodie’) with a percussion part for a bass drum with Turkish cymbals attached, to be played by a single musician. Only in the symphony's finale does Mahler mobilize all the resources of the post-Wagnerian orchestra in a large-scale dramatic narrative. Daemonic forces and heroic aspiration are colourfully symbolized in a movement whose expressive poles are represented on the one hand by the delicately-nuanced ‘Gesang’ theme that functions as a contrasting second subject, on the other by a triumphal march, whose final statement follows a cyclic flashback to the opening of the first movement (on whose falling 4ths it is based). Already, at the end of this work, Mahler was experimenting with ways of intensifying available techniques for creating an overwhelming volume of sound. He suggests in the score that the expanded horn section (he seems to have envisaged at least nine players at this point) should stand up, bells raised, in order to surmount the rest of the orchestral tutti with their peroration.

11. Second, Third and Fourth Symphonies, later ‘Wunderhorn’ songs.

Where the First Symphony, particularly in its original five-movement version, demonstrates clear affinities with Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique, the Second and Third Symphonies advertise their status as heirs to another source work of musical Romanticism in Germany: Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, as interpreted by Wagner in Das Kunstwerk der Zukunft (‘a richly gifted individual … took up into his solitary self the spirit of community that was absent from our public life’). Both symphonies include solo song and choral elements. Each was interpreted by Mahler (through annotations in the manuscript score, published movement titles or discursively elaborated narrative programmes) as articulating ideas of democratic inclusiveness and leading to a utopian vision through a drama of spiritual and even social struggle.

Surviving programmatic explanations, both formal and informal, of the Second Symphony (1888–94) suggest that its evolution and completion were dependent upon the narrative conceptualization of its structure. The programme Mahler drafted for a 1901 performance in Dresden indicates a progression from unresolvable subjective anxiety through a series of illustrative ‘intermezzos’ (movements 2–5) to a large-scale finale: a symphonic cantata for soloists, chorus and orchestra in which the progression from tension to resolution is reinterpreted as a narrative of apocalypse and subsequent redemption (the ‘Resurrection’ of the symphony's subsequent unofficial subtitle). Judeo-Christian mythology supplied certain of its details, but reinterpreted and even subverted in a striking manner. If Mahler's programmatic justification of his generically diverse suite of movements extended established 19th-century precedents, the symphony's scale and close matching of musical and conceptual details were highly original. The difference of rhetorical manner between the first- and second-subject material of the opening movement, respectively in C minor and E major, is rooted in post-Beethovenian symphonic practice as influenced by Romanticism and the 19th-century operatic overture. Mahler nevertheless extended the principle of contrast by opposing music of explosive urgency, generating a symphonic funeral march (C minor), to music of delicately focussed lyricism (E major) that is rich in harmonic, textural and expressive signs denoting a fragile and alienated subjectivity. This is far removed from the gloomy reality of the funeral rites which the movement's abandoned title (‘Todtenfeier’) signalled as its primary mood: one which has been linked (see Hefling, H(ii) 1988–9) to an unstated programme derived from the Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz's Todtenfeier, as translated into German by Mahler's friend Siegfried Lipiner. Mahler himself described it as evoking the funeral of the hero of his First Symphony, the prologue to its sequel representing an angry and questioning meditation upon mortality.