Henry T. Finck

Bethel, Missouri, 1854 - 1926, Rumford Falls, Maine

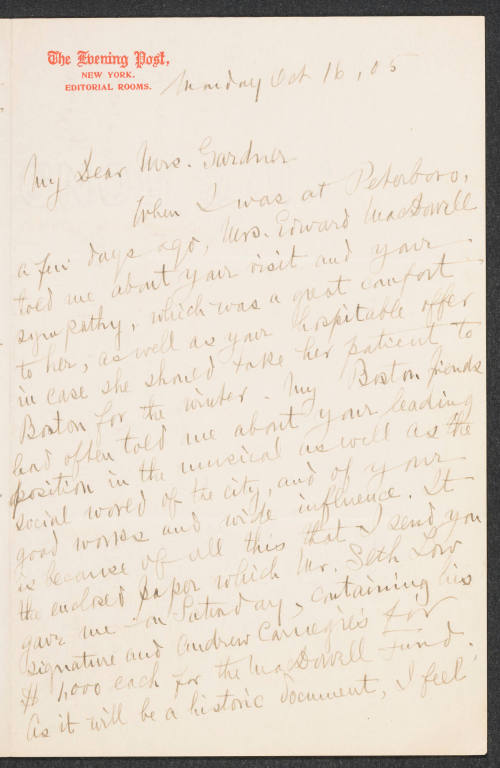

From 1881 to 1924 Finck was music critic for the Nation and the New York Evening Post. After 1882 he lectured at the National Conservatory of Music. He wrote twenty-two books, some of them compilations of his journalistic essays on music, others on such varied topics as anthropology, psychology, diet, and horticulture. Influential as well were his elegant editions of art songs. Finck was most important, however, for championing the music of Wagner, Liszt, Chopin, Greig, and MacDowell in the United States. James Huneker, his rival and friend, once wrote to him, "You are not only the first Chopin apostle, but also the first Liszt, the first Wagner in America!"

In 1890 Finck married Abbie Helen Cushman; they had no children. A pupil of Rafael Joseffy, the master piano teacher at the National Conservatory, she aided her husband in his career. Evidence of their close partnership and shared tastes was Finck's admission that he "palmed off some of his wife's music criticism" as his own.

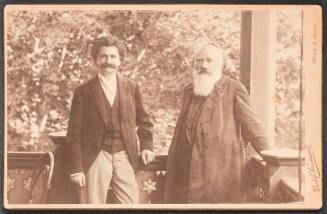

Finck inaugurated an American style of music criticism that made profound, informed, and mostly correct judgments (in a rare misassessment, he detested Brahms) in a breezy, vernacular prose that one could understand without explication or detailed technical knowledge. In a review of the composer-conductor Gustav Mahler's interpretation of the second-movement funeral march from Beethoven's Eroica symphony, Finck noted both his admiration for Mahler and his contempt for the rival music critic Henry E. Krehbiel. "Yes, Mahler was the greatest of Beethoven conductors, and acknowledged as such abroad. Yet in New York he was persistently abused, and, strange to say, most violently by Krehbiel, the American high priest of Beethoven." Discussing a performance by his friend the violinist Fritz Kreisler of a Mozart piece, Finck wrote, "Kreisler looked very modest while playing these cadenzas, but I bet my bottom dollar that these glorious episodes were only one-third Mozart, two-thirds Kreisler." Finck proudly published the Boston critic Philip Hale's tale that "whenever a Brahms symphony was played I either whiled away time by reading a book or looked for the nearest fire escape."

Despite such a blind spot, Finck was the model of the progressive spirit who championed the new and the best in music, irrespective of academic opinion or establishment support. He was opinionated but had great respect and even affection for those colleagues with whom he most strongly disagreed. All in all it was a logical and consistent position for a musical arbiter who did not like Richard Strauss or Debussy but admired Stravinsky, Victor Herbert, and George Gershwin. Finck died in Rumford Falls, Maine.

Bibliography

The chief source to date for biographical material is Finck's autobiography, My Adventures in the Golden Age of Music (1926), published shortly after his death. Finck's other writings outside of the pages of the New York Evening Post, the Nation, and Etude may be found in such psychological-anthropological works as Romantic Love and Personal Beauty (1887), Primitive Love and Love Stories (1899), Food and Flavor (1913), Girth Control (1923), and Gardening with Brains (1922). His friendship with living personalities as well as his zeal for the "new" orchestral and operatic music resulted in a number of biographies and appreciations of composers and works neglected by the academy: Chopin and Other Musical Essays (1889), Wagner and His Works: The Story of His Life, with Critical Comments (1893), Pictorial Wagner (1899), Songs and Song-Writers (1900), Edvard Grieg (1906), Grieg and His Music (1909), Success in Music and How It Is Won (1909), Massenet and His Operas (1910), Richard Strauss: The Man and His Works (1917), and Musical Progress: A Series of Practical Discussions of Present Day Problems in the Tone World (1923). Two academic treatments of music criticism in New York deal somewhat with Finck's contributions: M. Sherwin, "The Classical Age of New York Musical Criticism, 1880-1920: A Study of Henry T. Finck, James G. Huneker, W. J. Henderson, Henry E. Krehbiel, and Richard Aldrich (master's thesis, City College, City Univ. of New York, 1972); and B. Mueser, "The Criticism of New Music in New York: 1919-1929" (Ph.D. diss., City Univ. of New York, 1975). Factual and sympathetic articles about his career are to be found in Grove's Dictionary, American Supplement (1944), p. 203-4; Margery M. Lowens, Finck, Henry T(heophilus), in The New Grove Dictionary of American Music, vol. 2 (1986), p. 125; and Louis G. Elson, The History of American Music (1904), pp. 315-19, which also presents a full-page photographic portrait.

Victor Fell Yellin

Back to the top

Citation:

Victor Fell Yellin. "Finck, Henry Theophilus";

http://www.anb.org/articles/18/18-00391.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 14:37:22 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

St. Petersburg, 1878 - 1936, Detroit

Geisenheim, Germany, 1826 - 1890, Beverly, Massachusetts

Votkinsk, Russia, 7 May 1840 - 6 November 1893, Saint Petersburg

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1857 - 1921, New York, New York

Boston, 1848 - 1913, Vevey, Switzerland

Flushing, New York, 1878 - 1939, Franconia, New Hampshire

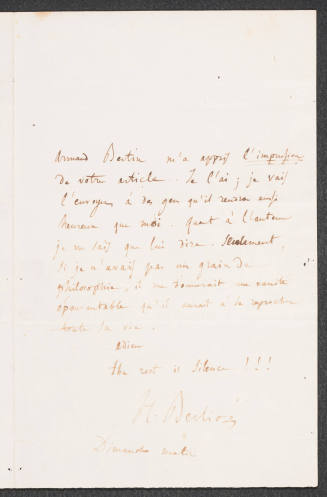

La Côte-Saint-André, France, 1803 - 1869, Paris

New Malden, Kingston-upon-Thames, England, 1873 - 1951, Miami, Florida