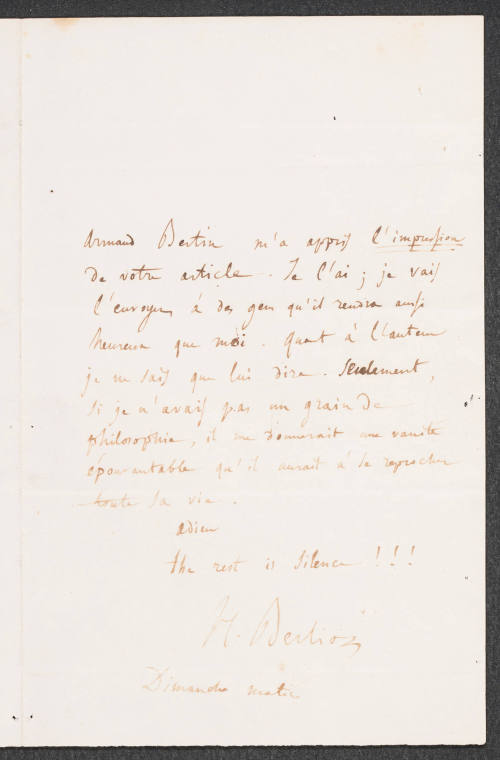

Hector Berlioz

La Côte-Saint-André, France, 1803 - 1869, Paris

Early Career

The birthplace of Berlioz was a village about 35 miles (56 km) northwest of Grenoble in the French Alps. France was at war; the schools were disrupted; and Berlioz received his education from his father, an enlightened and cultured physician, who gave him his first lessons in music as well as in Latin. But, like many composers, Berlioz received in his early years little formal training in music. He worked out for himself the elements of harmony and by his 12th year was composing for local chamber-music groups. With help from performers, he learned to play the flute and the guitar, becoming a virtuoso on the latter.

In 1821 his father sent him to Paris to study medicine, and for a year he followed his courses faithfully enough to obtain his first degree in science. He took every opportunity to go to the Paris-Opéra, however, where he studied, score in hand, the whole repertory, in which the works of Gluck had for him the most appeal and authority. His musical vocation had become so clear in his mind that he contrived to be accepted as a pupil of Jean-François Lesueur, professor of composition at the Paris Conservatoire. This led to disagreements between Berlioz and his parents that embittered nearly eight years of his life. He persevered, took the obligatory courses at the Conservatoire, and in 1830 won the Prix de Rome, having received second prize in an earlier competition. These successes pacified his family but were, in a sense, incidental to his career, for in the same year he had finished and obtained a performance of his first great score, which is also a seminal work in 19th-century music, the Symphonie fantastique.

It was in some respects unfortunate that, instead of being able to follow up this success, Berlioz was required, under the terms of his prize, to spend three years abroad, two of them in Italy. During his long Paris apprenticeship, he had experienced the “revelation” of two modern musicians, Beethoven and Weber, and of two great poets, Shakespeare and Goethe. He had meanwhile fallen in love, at a distance, with Harriet Smithson, a Shakespearean actress who had taken Paris by storm; and, on the rebound from this rather one-sided attachment, he had become engaged to a brilliant and beautiful pianist, Camille Moke (later Mme Pleyel). In leaving Paris, Berlioz was not only leaving a flirtatious fiancée and the artistic environment that had stimulated his powers; he was also leaving the opportunity to demonstrate what his genius saw that modern French music should be. The public was content with the “Paris school,” dating back to the 1780s, and there is evidence that all Europe (including the Vienna of Beethoven and Schubert) accepted the productions of André Grétry, Étienne Méhul, Luigi Cherubini, and their followers as leading the musical world.

Berlioz wanted to bring forward the work of Weber and Beethoven (including the last quartets) and add contributions of his own. He also preached, for the sake of dramatic expression in music, a return to the master of the stage, Gluck, whose works he knew by heart. These three musicians were all in some sense dramatists, and to Berlioz music must first and foremost be dramatically expressive. This doctrine he had begun to expound in his first musical reviews, as early as 1823, and, with the sharpness and strength of an early vision, it remained the artistic creed of his mature years. When one understands its intellectual and intuitive basis, one understands also the reasons for his dynamic career. What may look like self-seeking—the unceasing effort to have his music played—was, in fact, the dedication of his tremendous energies to a cause, often at the expense of his own creative work. The result of his many journeys to Germany, Belgium, England, Russia, and Austria-Hungary was that he taught the leading orchestras of Europe a new style and, through them, taught a new idiom to the young composers and critics who flocked wherever he went.

Before these “campaigns” began, however, Berlioz had his time of reflection in Italy. He wrote in his Mémoires (1870) how unproductive he was after the rich output of the Paris years, which had brought forth an oratorio, numerous cantatas, two dozen songs, a mass, part of an opera, two overtures, a fantasia on Shakespeare’s Tempest, and eight scenes from Goethe’s Faust, as well as the Symphonie fantastique. Even in Italy, however, Berlioz filled notebooks, met the Russian composer Mikhail Glinka, made a lifelong friend of Mendelssohn, and tramped the hills with his guitar over his shoulder, playing for the peasants and banditti whose meals he shared. The impressions gathered in Italy remained a source of both musical and dramatic inspiration down to the last of his works, Les Troyens and Béatrice et Bénédict (first performed 1862). Meanwhile, his love affair stagnating and his impatience with life at the Villa Medici in Rome becoming acute, he returned to France after 18 months and forfeited part of his prize.

Mature Career

Back in Paris, he set about conquering it anew. He put together a collection of earlier pieces in a form then fashionable, the monodrama, or recitation by one actor interspersed with musical scenes. Since the Symphonie fantastique had ended with the death and demonic torments of the protagonist, Berlioz called his new work Le Retour à la vie (later Lélio, after the hero’s name). First performed in 1832, this concoction, which contains three or four delightful pieces, enjoyed great success, and Berlioz had reason to think himself launched again.

A series of accidents brought him in touch with the actress Harriet Smithson, whom he married on October 3, 1833. The marriage did not last, though for some years the couple led a peaceful existence at Montmartre in the house that Maurice Utrillo later never tired of painting. Among the visitors there were the young poets and musicians of the Romantic movement, including Alfred de Vigny and Chopin. It was there that Berlioz’s only child, Louis, was born and also where he composed his great Requiem, the Grande Messe des morts (1837), the symphonies Harold en Italie (1834) and Roméo et Juliette (1839), and the opera Benvenuto Cellini (Paris, 1838).

Excerpt from Harold en Italie, by Hector Berlioz, 1834. Written for viola and orchestra, the piece is played here by viola and piano.

Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

It was after the premiere of Harold en Italie that Berlioz had the astonishing experience of seeing the famous violin virtuoso Paganini fall at his feet and declare that he was a genius destined to carry on the new musical tradition initiated by Beethoven. The next day Berlioz received 20,000 francs with a letter from Paganini repeating this judgment. Using the money to free himself from journalistic drudgery, Berlioz composed the choral symphony Roméo et Juliette, dedicated to Paganini.

In Paris it was always expected that a composer, regardless of his bent, should be tested at the Opéra. Berlioz’s friends intrigued to procure the assignment of a libretto. An adaptation of Benvenuto Cellini’s autobiography was secured, and Berlioz finished his score in a short time. The intrigue now passed to the other side, which saw to it that the production of Benvenuto Cellini at the Opéra failed. From this blow the work itself and the composer’s reputation in France never recovered during his lifetime. The score is a masterpiece, and the attribution of the failure to the libretto shows ignorance of the qualities of both the libretto and the music.

The Requiem of 1837 had been a government commission for a ceremonial occasion designed to encourage the Rome laureate. The request to compose another work for a public ceremony—the Symphonie funèbre et triomphale (Funeral Symphony) for military band, chorus, and strings, commissioned for the 10th anniversary of the July Revolution (1840)—was intended as a partial solace for the defeat of Benvenuto Cellini. A few years before, Berlioz’s literary gifts had won him the post of music critic for the leading Paris newspaper, the Journal des Débats, and his employers wielded political influence. Once again, there were intrigues, but the score of the Funeral Symphony was ready for the inauguration of the Bastille column. Unfortunately, the music was drowned out by the drum corps, a disaster that Berlioz repaired by giving the work the following month at a concert hall. This was the score that Wagner, then seeking fame in Paris, admired so wholeheartedly.

Berlioz was able to put Wagner in the way of some musical journalism and thus began a fitful connection of 30 years between the two men whose influence on modern music still resembles a battle of ideals: Berlioz aiming at the creation of drama in and through music alone; Wagner at marriage of symphony with opera. Although Berlioz and Wagner met again in London in 1855 and found each other congenial, their philosophical differences generally kept them apart.

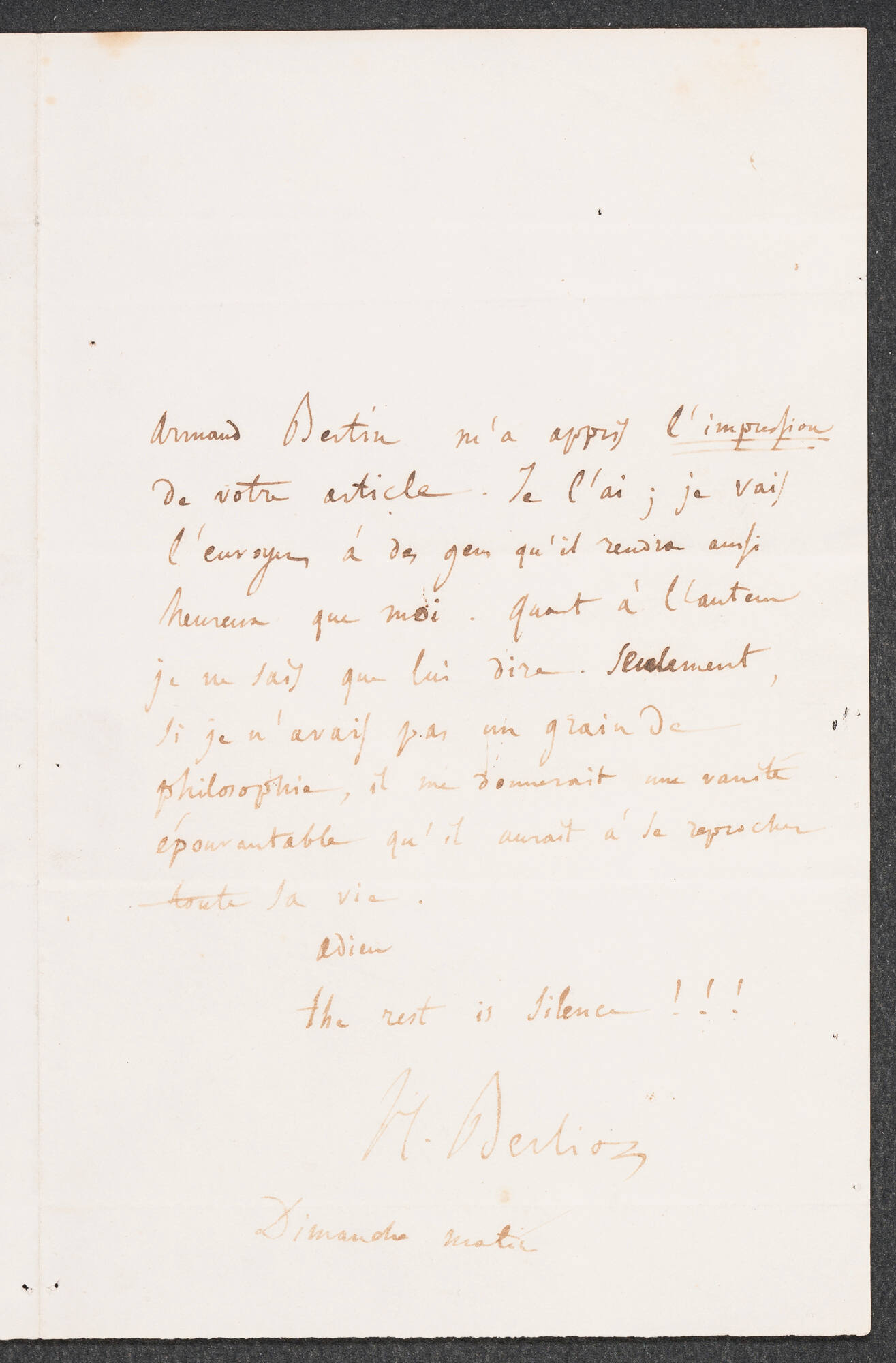

After 1840 Berlioz’s life consisted of a series of tours across Europe. The last of these was an exhausting series of concerts in St. Petersburg and Moscow in 1867, when he was desperately ill. But it had the effect of introducing the Russian Five, notably Mussorgsky, to his style through his manuscript scores and his conducting. For Berlioz was the first of the virtuoso conductors, having made himself such in order to supply the deficiencies of men who were unable to direct the new music according to the new canon: play what is written. Moreover, the rhythmical difficulties of his scores and the unfamiliar curve of his melodies disconcerted many. The orchestras themselves had to be taught a new precision, vigour, and ensemble, and this was Berlioz’s handiwork. Wagner’s memoirs bear testimony to this “revelation of a new world,” which he experienced at Berlioz’s hands in 1839.

On orchestration itself (and, even more important, on instrumentation) Berlioz produced the leading treatise, Traité d’instrumentation et d’orchestration modernes (1844). Much more than a technical handbook, it served later generations as an introduction to the aesthetics of expressiveness in music. As Albert Schweitzer has shown, its principle is as applicable to Bach as to Berlioz, and it is in no way governed by considerations of so-called program music. To this last-named genre of dubious repute, Berlioz did not contribute more than the printed “story” of his first symphony, which is intelligible as music, without any program.

Among Berlioz’s dramatic works, two became internationally known: La Damnation de Faust (1846) and L’Enfance du Christ (1854). Two others began to emerge from neglect after World War I: the massive two-part drama Les Troyens (1855–58), based on Virgil’s story of Dido and Aeneas, and the short, witty comedy Béatrice et Bénédict, written between 1860 and 1862 and based on Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing. For all these Berlioz wrote his own librettos. He also wrote a Te Deum (1849; perfomed 1855), which is a fitting counterpart to the Requiem, and between 1843 and 1856 he orchestrated his songs, including the song cycle Les Nuits d’été (Summer Nights). Among his best known overtures are Le Roi Lear (1831), Le Carnaval romain (1844), based on material from Benvenuto Cellini, and Le Corsaire (1831–52).

In Berlioz’s final years he was incapacitated by illness and saddened by many deaths. His first wife, from whom he was separated but to whom he still felt a deep attachment, died in 1854; his second wife, Maria Recio, who had been his companion for many years and whom he had married when he became a widower, died suddenly in 1862. Finally, his son, Louis, who was a sea captain and on whom he concentrated the affection of his declining years, died of yellow fever in Havana at the age of 33.

Legacy

The outstanding characteristics of Berlioz’s music—its dramatic expressiveness and variety—account for the feeling of attraction or repulsion that it produces in the listener. Its variety also means that devotees of one work may dislike others, as one finds lovers of Shakespeare who detest Othello. But Berlioz also presents a particular difficulty of musicianship in being closer to the true sources of music than to its German, Italian, or French conventions; his melody is abundant and extended and is often disconcerting to the lover of four-bar phrases; his harmony may be obvious or subtle, but it is always functional and frequently depends on elements of timbre; his modulations can be harsh and may even seem harsher than they would in another composer, because he uses his effects sparingly and achieves much by small means and adroit contrasts. This is also true of his orchestration, generally light and transparent, never pasty. As George Bernard Shaw said: “Call no conductor sensitive in the highest degree to musical impressions until you have heard him in Berlioz and Mozart.”

The Belgian composer César Franck once said that Berlioz’s whole output is made up of masterpieces. He meant by this that each of the composer’s dozen great works was the realization of a conception distinct from all the others, rather than successive efforts to attain perfection in the last or best of a series. Franck’s judgment is borne out by the fact that, unlike many composers, Berlioz almost never repeats himself. Rather, he created a fresh style for each of his subjects, with the result that familiarity with one is no guarantee of ready access to another. Nothing could be less alike than the Symphonie funèbre et triomphale and Roméo et Juliette or than the Requiem and L’Enfance du Christ. To be sure, Berlioz’s harmonic system seems the same throughout, partly because it deviates so noticeably from common expectation and partly because its nuances are only now being appreciated for what they are, instead of being looked upon as clumsy attempts to do something else. Again, his melody and free counterpoint everywhere carry his mark—the sinewy originality and dynamic equilibrium of the former, the ingeniously careless independence of the latter. Yet, out of these characteristic elements Berlioz makes a radically different atmosphere for each of his dramas and within them for each of his dramatis personae. Only a repeated hearing of any given work discloses all the power and art (including what would now be called psychology) that it contains. This does not mean that these works are without flaw; it does mean that they embody unique conceptions, to be taken for what they have to give and which no other composer provides.

In the creation of drama and atmosphere, Berlioz excels in scenes of melancholy, introspection, love—gentle or passionate—the contemplation of nature, and the tumult of crowds. His intention throughout is to combine truth with musical sensations, be they powerful or (to quote Shaw again) “wonderful in their tenuity and delicacy, unearthly, unexpected, unaccountable.”

Much might be added or quoted that would show the extent to which Berlioz’s music still needs careful and dispassionate study. In 1935 the respected British musicologist Sir Donald Tovey, who had not before heard Les Troyens, declared that it is “one of the most gigantic and convincing masterpieces of music drama.” And, he went on, “You never know where you are with Berlioz.” What is certain is that books that date from the 19th century or echo its views, with or without a bias toward Wagner or Debussy, will mislead the student and possibly close the ears of the listener. It is easy to represent Berlioz as merely a craftsman in tone colour who helped develop the resources of the orchestra. But with the repeated performance of the major works all over the Western world, the more comprehensive judgment has come to prevail that Berlioz is a dramatic musician of the first rank. Before 1945 the Berlioz repertoire was limited to the Symphonie fantastique and a few brief extracts. The great works, done once and usually with insufficient preparation, produced little effect and confirmed the wisdom of letting them lie. The advent of long-playing records radically altered the situation. Audiences can now judge the interpretations that they are being given, and thus they hear Berlioz performances with a knowledge and critical attention comparable to those with which they hear other composers.

Jacques Barzun

CITE

Contributor:

Jacques Barzun

Article Title:

Hector Berlioz

Website Name:

Encyclopædia Britannica

Publisher:

Encyclopædia Britannica, inc.

Date Published:

March 01, 2018

URL:

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hector-Berlioz

Access Date:

October 24, 2018

I.S.

Louis-Hector Berlioz (/?b??rlio?z/; French: [?kt?? b??ljoz]; 11 December 1803 – 8 March 1869) was a French Romantic composer. His output includes orchestral works such as the Symphonie fantastique (1830) and Harold in Italy (1834); choral pieces, among which are his Requiem (1837) and L'enfance du Christ (1854); three operas: Benvenuto Cellini (1838), Les Troyens (1858) and Béatrice et Bénédict (1862); and works of hybrid genres such as the "dramatic symphony" Roméo et Juliette (1839) and the "dramatic legend" La damnation de Faust (1846).

As the elder son of a provincial doctor, Berlioz was expected to follow his father into medicine, and he attended a medical college in Paris before defying his family and taking up music as a profession. His independence of mind and refusal to follow traditional rules and formulas put him at odds with the conservative musical establishment of Paris. He briefly moderated his style enough to win France's premier music prize, the Prix de Rome, in 1830, but he learned little from the academics of the Paris Conservatoire. His music divided opinion for many years between those who thought him an original genius and those who thought his music lacked form and coherence.

A romantic in his personal life as well as in his art, Berlioz fell in love in 1826 with an Irish Shakespearean actress, Harriet Smithson, and pursued her obsessively; she finally accepted him in 1833. Their marriage was happy at first, but eventually foundered. She inspired his first major success, the Symphonie fantastique, in which an idealised depiction of her occurs throughout.

Berlioz completed three operas, the first of which, Benvenuto Cellini, was an outright failure. The second, the huge epic Les Troyens (The Trojans) was too large in scale for the opera managements of the period to cope with, and was never staged in its entirety during his lifetime. His last opera, Béatrice et Bénédict, based on Shakespeare's comedy Much Ado About Nothing, was a success at its premiere, but did not gain a secure place in the regular operatic repertoire. Meeting only occasional success in France as a composer, Berlioz increasingly turned to conducting, in which he gained an international reputation. He was highly regarded in Germany, Britain and Russia both as a composer and as a conductor. To supplement his earnings he wrote musical journalism throughout much of his career; some of it has been preserved in book form, including his Treatise on Instrumentation (1844), which was influential throughout the 19th century and into the 20th. He died in Paris at the age of 65.

Life and career

1803–1821: Early years

Berlioz was born on 11 December 1803,[n 1] the eldest child of Louis Berlioz (1776–1848), a physician, and his wife, Marie-Antoinette Joséphine, née Marmion (1784–1838).[n 2] His birthplace was the family home in the commune of La Côte-Saint-André in the département of Isère, in south-eastern France. His parents had five more children, three of whom died in infancy;[7] their surviving daughters, Nanci and Adèle, remained close to him throughout their lives.[6][8]

oil painting of head and shoulders of white man in early 19th-century costume, with receding grey hair and neat side-whiskers

Louis Berlioz, the composer's father

Berlioz's father, a respected local figure, was a progressively-minded doctor, credited as the first European to practise and write about acupuncture.[9] He was an agnostic, with a liberal outlook; his wife was a strict Roman Catholic of less flexible views.[10] It was he rather than she who was responsible for much of the young Berlioz's education.[11] After briefly attending a local school when he was about ten, Berlioz was educated at home by his father. He recalled in his Mémoires that he enjoyed geography, especially books about travel, to which his mind would sometimes wander when he was supposed to be studying Latin; the classics nonetheless made an impression on him, and he was moved to tears by Virgil's account of the tragedy of Dido and Aeneas.[12] Later he studied philosophy, rhetoric, and – because his father planned a medical career for him – anatomy.[13]

Music did not feature prominently in the young Berlioz's education. His father gave him basic instruction on the flageolet, and he later had flute and guitar lessons with local teachers. He never studied the piano, and throughout his life played haltingly at best.[6] He later contended that this was an advantage because it "saved me from the tyranny of keyboard habits, so dangerous to thought, and from the lure of conventional harmonies".[14]

At the age of twelve Berlioz fell in love for the first time. The object of his affections was an eighteen-year-old neighbour, Estelle Dubœuf. He was teased for what was seen as a boyish crush, but something of his early passion for Estelle endured all his life.[15] He poured some of his unrequited feelings into his early attempts at composition. Trying to master harmony, he read Rameau's Traité de l'harmonie, which proved incomprehensible to a novice, but Charles-Simon Catel's simpler treatise on the subject made it clearer to him.[16] He wrote several chamber works as a youth,[17] subsequently destroying the manuscripts, but one theme that remained in his mind reappeared later as the A-flat second subject of the overture to Les francs-juges.[14]

1821–1824: Medical student

In March 1821 Berlioz passed the baccalauréat examination at the University of Grenoble – it is not certain whether at the first or second attempt[18] – and in late September, aged seventeen, he moved to Paris. At his father's insistence he enrolled at the School of Medicine of the University of Paris.[19] He had to fight hard to overcome his revulsion at dissecting bodies, but in deference to his father's wishes, he forced himself to continue his medical studies.[20]

exterior of old building in neo-classical style

The Opéra, in the Rue le Peletier, Paris, c. 1821

The horrors of the medical college were mitigated thanks to an ample allowance from his father, which enabled him to take full advantage of the cultural, and particularly musical, life of Paris. Music did not at that time enjoy the prestige of literature in French culture,[6] but Paris nonetheless possessed two major opera houses and the country's most important music library.[21] Berlioz took advantage of them all. Within days of arriving in Paris he went to the Opéra, and although the piece on offer was by a minor composer, the staging and the magnificent orchestral playing enchanted him.[n 3] He went to other works at the Opéra and the Opéra-Comique; at the former, three weeks after his arrival he, saw Gluck's Iphigénie en Tauride, which thrilled him. He was particularly inspired by Gluck's use of the orchestra to carry the drama along. A later performance of the same work at the Opéra convinced him that his vocation was to be a composer.[23]

The dominance of Italian opera in Paris, against which Berlioz later campaigned, was still in the future,[24] and at the opera houses he heard and absorbed the works of Étienne Méhul and François-Adrien Boieldieu, other operas written in the French style by foreign composers, particularly Gaspare Spontini, and above all five operas by Gluck.[24][n 4] He began to visit the Paris Conservatoire library, in between his medical studies, seeking out scores of Gluck's operas and making copies of parts of them.[25] By the end of 1822 he felt that his attempts to learn composition needed to be augmented with formal tuition, and he approached Jean-François Le Sueur, director of the Royal Chapel and professor at the Conservatoire, who accepted him as a private pupil.[26]

In August 1823 Berlioz made the first of many contributions to the musical press: a letter to the journal Le Corsaire defending French opera against the incursions of its Italian rival.[27] He contended that all of Rossini's operas put together could not stand comparison with even a few bars of those of Gluck, Spontini or Le Sueur.[28] By now he had composed several works including Estelle et Némorin and Le Passage de la mer Rouge (The Crossing of the Red Sea) – both now lost.[29]

In 1824 Berlioz graduated from the medical school,[29] after which he abandoned medicine, to the strong disapproval of his parents. His father suggested law as an alternative profession, but refused to countenance music as a career.[30][n 5] He reduced and sometimes withheld his son's allowance, and Berlioz went through some years of financial hardship.[6]

1824–1830: Conservatoire student

In 1824 Berlioz composed a Messe solennelle. It was performed twice, after which he suppressed the score, which was thought lost until a copy was discovered in 1991. During 1825 and 1826 he wrote his first opera, Les francs-juges, which was not performed and survives only in fragments, the best known of which is the overture.[32] In later works he reused parts of the score, such as the "March of the Guards", which he incorporated four years later in the Symphonie fantastique as the "March to the Scaffold".[6]

young white woman in Shakespearean costume, with flowing gown and enormous, flowing kerchief, gazing to her left and striking a romantic pose

Harriet Smithson as Ophelia

In August 1826 Berlioz was admitted as a student to the Conservatoire, studying composition under Le Sueur and counterpoint and fugue with Anton Reicha. In the same year he made the first of his four attempts to win France's premier music prize, the Prix de Rome, and was eliminated in the first round. The following year, to earn some money, he joined the chorus at the Théâtre des Nouveautés.[29] He competed again for the Prix de Rome, submitting the first of his Prix cantatas, La mort d'Orphée, in July. Later that year he attended productions of Shakespeare's Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet at the Théâtre de l'Odéon given by Charles Kemble's touring company. Although at the time Berlioz spoke hardly any English he was overwhelmed by the plays – the start of a lifelong passion for Shakespeare. He also conceived a passion for Kemble's leading lady, Harriet Smithson – his biographer Hugh Macdonald calls it "emotional derangement" – and obsessively pursued her, without success, for several years. She refused even to meet him.[4][6]

The first concert of Berlioz's music was given in May 1828, when his friend Nathan Bloc conducted the premieres of the overtures Les francs-juges and Waverley and other works. The hall was far from full, and Berlioz lost money,[n 6] but he was greatly encouraged by the applause from musicians in the audience, including his Conservatoire professors, the directors of the Opéra and Opéra-Comique, and the composers Auber and Hérold, and by the vociferous approval of the performers.[34]

Keen to read Shakespeare in the original, Berlioz started learning English in 1828. At around the same time he encountered two more creative inspirations: he heard Beethoven's third, fifth and seventh symphonies performed at the Conservatoire,[n 7] and he read Goethe's Faust in Gérard de Nerval's translation.[29] Beethoven became both an ideal and an obstacle for Berlioz – an inspiring predecessor but a daunting one.[36] Goethe's work was the basis of Huit scènes de Faust (Berlioz's Opus 1), premiered the following year and reworked and expanded much later as La damnation de Faust.[37]

1830–1832: Prix de Rome

Berlioz was largely apolitical, and neither supported nor opposed the July Revolution of 1830, but when it broke out he found himself in the middle of it. He recorded events in his Mémoires:

I was finishing my cantata when the revolution broke out ... I dashed off the final pages of my orchestral score to the sound of stray bullets coming over the roofs and pattering on the wall outside my window. On the 29th I had finished, and was free to go out and roam about Paris till morning, pistol in hand.[38]

The cantata was La mort de Sardanapale, with which he won the Prix de Rome. His entry the previous year, La mort de Cléopâtre, had attracted disapproval from the judges because to highly conservative musicians it "betrayed dangerous tendencies", and for his 1830 offering he carefully modified his natural style to meet official approval.[6] During the same year he wrote the Symphonie fantastique and became engaged to be married.[39]

drawing of young white woman, with short dark hair, in plain early 19th century dress

Marie ("Camille") Moke, later Pleyel

By now recoiling from his obsession with Smithson, Berlioz fell in love with a nineteen-year-old pianist, Marie ("Camille") Moke. His feelings were reciprocated, and the couple planned to be married.[40] In December Berlioz organised a concert at which the Symphonie fantastique was premiered. Protracted applause followed the performance, and the press reviews expressed both the shock and the pleasure the work had given.[41] Berlioz's biographer David Cairns calls the concert a landmark not only in the composer's career but in the evolution of the modern orchestra.[42] Franz Liszt was among those attending the concert; this was the beginning of a long friendship. Liszt later transcribed the entire Symphonie fantastique for piano to enable more people to hear it.[43]

Shortly after the concert Berlioz set off for Italy: under the terms of the Prix de Rome, winners studied for two years at the Villa Medici, the French Academy in Rome. Within three weeks of his arrival he went absent without leave: he had learnt that Marie had broken off their engagement and was to marry an older and richer suitor, Camille Pleyel, the heir to the Pleyel piano manufacturing company.[44] Berlioz made an elaborate plan to kill them both (and her mother, known to him as "l'hippopotame"),[45] and acquired poisons, pistols and a disguise for the purpose.[46] But by the time he reached Nice on his journey to Paris he thought better of the scheme, abandoned the idea of revenge, and successfully sought permission to return to the Villa Medici.[47][n 8] He stayed for a few weeks in Nice and wrote his King Lear overture. On the way back to Rome he began work on a piece for narrator, solo voices, chorus and orchestra, Le retour à la vie (The Return to Life, later renamed Lélio), a sequel to the Symphonie fantastique.[47]

painting of young white man with abundant curly brown hair and side-whiskers, wearing bright red cravat

Berlioz when a student at the Villa Medici, 1832

Berlioz took little pleasure in his time in Rome. His colleagues at the Villa Medici, under their benevolent principal Horace Vernet, made him welcome,[49] and he enjoyed his meetings with Felix Mendelssohn, who was visiting the city,[n 9] but he found Rome distasteful: "the most stupid and prosaic city I know; it is no place for anyone with head or heart."[6] Nonetheless, Italy had an important influence on his development. He visited many parts of it during his residency in Rome. Macdonald com

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Hamburg, Germany, 1809 - 1847, Leipzig, Germany

Boston, 1848 - 1913, Vevey, Switzerland

Munich, 1864 - 1949, Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany

Geisenheim, Germany, 1826 - 1890, Beverly, Massachusetts