Camille Saint-Säens

Paris, 1835 - 1921, Algiers

(b Paris, 9 Oct 1835; d Algiers, 16 Dec 1921 ). French composer, pianist, organist and writer. Like Mozart, to whom he was often compared, he was a brilliant craftsman, versatile and prolific, who contributed to every genre of French music. He was one of the leaders of the French musical renaissance of the 1870s.

1. Life.

His father, Jacques-Joseph-Victor Saint-Saëns (1798–1835), descended from a Norman agricultural family, served as a clerk at the Ministry of the Interior and in 1834 married Clémence Collin (1809–88); the couple moved in with Clémence's aunt and uncle, the Massons. Within a year of the wedding, however, both M. Masson and Jacques Saint-Saëns had died, the latter just three months after the birth of his son. After spending two years in a nursing home in Corbeil, the tubercular Camille was brought up by his mother and aunt. He was taught to play the piano from the age of three by Mme Masson, and at the age of ten made his formal début at the Salle Pleyel with a programme that included Beethoven's Piano Concerto in C minor and Mozart's Concerto in B? k450, for which he wrote his own cadenza. He performed everything from memory, which was considered an unusual feat at the time. Stamaty recommended that he should also study composition with Pierre Maleden, a former pupil of Fétis and Gottfried Weber, whom Saint-Saëns was to consider an incomparable teacher.

Saint-Saëns showed the same quickness in his general education, studying the French classics, religion, Latin and Greek and acquiring a taste for mathematics and the natural sciences, including astronomy, archaeology and philosophy, subjects on which he was later to write with enthusiasm. When he sold the publishing rights of his Six duos for harmonium and piano to Girod for 500 francs in 1858, he used the proceeds to buy a telescope.

Saint-Saëns entered the Paris Conservatoire in 1848 and studied the organ with Benoist, winning the premier prix in 1851. In the same year he began to study composition and orchestration with Halévy, and also took lessons in accompaniment and singing. A scherzo for small orchestra, a Symphony in A, the choral piece Les djinns, two romances and a number of incomplete works date from this period. Although he failed to win the Prix de Rome, his Ode à Sainte-Cécile won first prize in a competition organized by the Société Sainte-Cécile, Bordeaux, in 1852. He began two opéras comiques at about this time, but neither one was completed. In 1854 he wrote the overture (and began a duo) to a scenario suggested by Jules Barbier; this was performed and published only in 1913. Meanwhile, he completed a number of songs, the Piano Quintet op.14 and the Symphony ‘Urbs Roma’, which won another competition organized by the Société Sainte-Cécile in 1857. At this time he also contributed to the complete edition of the works of Gluck; he was subsequently to work on editions of works by Beethoven, Liszt, Mozart and the French clavecinists.

Saint-Saëns's gifts early won him the friendship and patronage of Pauline Viardot, Gounod, Rossini and Berlioz; Berlioz said of him: ‘he knows everything but lacks inexperience’. Liszt also was much impressed by him as a pianist and a composer. In 1853 he was made organist of St Merry, where his Mass op.4, dedicated to the Abbé Gabriel, was performed in 1857. In gratitude the Abbé invited Saint-Saëns to accompany him on a visit to Italy which inaugurated a lifetime of travel for the young composer. Also in 1857, he was nominated to the Madeleine, where he remained until 1877; it was there that Liszt heard him improvising and hailed him as the greatest organist in the world. At this time Saint-Saëns composed the Symphony no.2 and several lyric scenes. He was also active in promoting the music of a number of other composers. He was one of the first to appreciate Wagner and defended both Tannhäuser and Lohengrin against the attacks of his elders. Schumann was another modern composer whom he persisted in playing despite the disapproval of conservative opinion. At his own expense he also organized and conducted concerts of music by Liszt – notably in March 1878 at the Salle du Théâtre Italien in gratitude for Liszt's encouragement of Samson et Dalila – and he was the first to play Liszt's symphonic poems in France. His own ventures in the form – Le rouet d'Omphale (1871), Phaéton (1873), Danse macabre (1874) and La jeunesse d'Hercule (1877) – popularized what was then a novelty and influenced subsequent developments in French music. Old music as well as new attracted his inquiring mind. He helped to revive interest in Bach (even converting his sceptical friend Berlioz to the cause) and did much to restore Mozart to his rightful place. Handel, little known then to French audiences, was the inspiration for Saint-Saëns's own oratorios, among them Le déluge (1875) and The Promised Land (1913).

The early 1860s were perhaps the most contented years of his life. His home environment was comfortable, and in public he enjoyed a formidable reputation as a composer and virtuoso pianist. His concert overture Spartacus won another competition organized by the Société Sainte-Cécile, and although his second attempt at the Prix de Rome in 1863 failed, in 1867 his cantata Les noces de Prométhée won a competition at the Grande Fête Internationale du Travail et de l'Industrie, whose jury included Rossini, Auber, Berlioz, Verdi and Gounod. He also performed his First Piano Concerto with some success in Paris and abroad during the 1860s, and his Sérénade op.15, dedicated to Princess Mathilde Bonaparte, was played at salons and in a prestigious concert at the Salle Pleyel attended by Berlioz, Gounod, Hiller, Liszt and others. Moreover, as a virtuoso pianist he was favourably placed to urge the claims of his own works, and although his material success and his sarcastic tongue made him many enemies, Gounod described him as ‘the French Beethoven’ (Bonnerot, 1914, p.126).

This period also included the only professional teaching appointment Saint-Saëns held. From 1861 to 1865 he taught at the Ecole Niedermeyer, an institution founded to improve musical standards in French churches. His students included Fauré, Messager and Gigout, who each became lifelong friends. Although strict about purely technical matters, Saint-Saëns was an inspiring teacher, and his students remembered the intellectual excitement he stimulated with his revelation of modern music and the arts in general. A more far-reaching result of his activities was the Société Nationale de Musique, which he founded with his colleague Romain Bussine in 1871. The motto ‘Ars Gallica’ underlined its purpose of encouraging and performing music by living French composers. The secretary was Alexis de Castillon, and other committee members included Fauré, César Franck and Lalo. The Société was to give important premières of works by Saint-Saëns, Chabrier, Debussy, Dukas and Ravel.

During the early 1870s Saint-Saëns wrote some articles for the journal Renaissance littéraire et artistique (signing himself ‘Phémius’). He also wrote for the Gazette musicale and the Revue bleue, displaying vigour and lucidity in his style and relishing lively arguments with his opponents, notably d'Indy. In 1876 he visited Bayreuth for the second series of performances of the Ring and wrote seven long articles for L'estafette and a series of pieces entitled ‘Harmonie et mélodie’ for Le Voltaire. In 1914 he wrote another series of articles, entitled ‘Germanophilie’ (Paris, 1916), in which he promoted a ban on German music during the war (particularly the works of Wagner); these prompted many articles and letters in response. Less controversial were his publications on the décor of ancient Roman theatres, on the instruments depicted in murals at Pompeii and Naples, and on philosophical problems.

In 1875 Saint-Saëns married the 19-year-old Marie-Laure Truffot. The marriage was not a success. Saint-Saëns's mother disapproved, and her son was difficult to live with. Two sons were born who died within six weeks of each other in 1878, one (aged two and a half) by falling out of a fourth-floor window, the second (aged six months) of a childhood malady. Saint-Saëns blamed his wife and three years later, while on holiday with her, suddenly vanished. A legal separation followed, and she never saw him again. She died in 1950 at Cauderan, near Bordeaux, in her 95th year. To a certain extent Saint-Saëns found an outlet for his affection and frustrated paternal instincts in a close relationship with Fauré. Indeed, as the years went by he tended to regard the latter's growing family as his own, and while he did all he could to further his protégé's career he became, for Fauré's wife and children, a benevolent uncle.

In 1877 his opera Le timbre d'argent had its première at the Théâtre Lyrique. The dedicatee of the opera, Albert Libon, died that year and bequeathed Saint-Saëns 100,000 francs to devote himself to composition. He wrote a requiem in memory of his benefactor which was performed on 22 May 1878 at St Sulpice. Saint-Saëns continued to perform at the Société Nationale, the chamber music society La Trompette and at the Salle Pleyel, composing a septet for La Trompette in 1880. His opera Henry VIII, to a libretto based on Shakespeare and Calderón, received its première in March 1883 and enjoyed great success. Saint-Saëns was elected to the Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1881, and was made an officier of the Légion d'Honneur in 1884.

The death of his mother in 1888 (his great-aunt had died in 1872) left him devastated. To recover his health he went to Algeria, which since his first visit in 1873 had been a favourite destination. During this time he had his possessions moved to Dieppe, where the Musée Saint-Saëns was established in July 1890. He continued to write, notably a series of articles entitled ‘Souvenir’ for the Revue bleue, and composed a number of songs. Further travels over the following years, usually based around concert tours, were to take him to southern Europe, South America (including Uruguay, for which he wrote a hymn, Partido colorado, for the national holiday on 14 July), the Canary Islands, Scandinavia and East Asia. While on holiday in Austria he dashed off Le carnaval des animaux in a few days (he forbade performances of the extravaganza, apart from ‘Le cygne’, during his lifetime, with an eye to his reputation). In Russia he performed in a series of seven concerts at St Petersburg sponsored by the Red Cross, and also met Tchaikovsky, with whom on one memorable occasion he danced an impromptu ballet to the piano accompaniment of Nikolay Rubinstein.

After his popularity in France began to wane, Saint-Saëns was still regarded in America and England as the greatest living French composer. During his first visit to America in 1906 he gave concerts at Philadelphia, Chicago and Washington, and in 1915 he returned to give a successful series of lectures and performances in New York and San Francisco. As early as 1871 he had made the first of many trips to England. He played before Queen Victoria and spent much time studying Handel manuscripts in the library at Buckingham Palace. In 1886 he was commissioned by the Philharmonic Society to write his Third Symphony, whose first performance he conducted in London. And in 1893 he conducted at Covent Garden a performance of Samson et Dalila in oratorio form – the English censor vetoed biblical topics in operas at that time. He was awarded honorary doctorates by the universities of Cambridge (1893) and Oxford (1907), and was made a Commander of the Victorian Order, following his composition of a march for the coronation of Edward VII in 1902.

He broke with the Société Nationale in 1886 when the committee decided that the works of foreign as well as French contemporary composers should be performed. This gave Saint-Saëns more time to write and compose for the theatre and to supervise performances of his operas in France and abroad. Although he was the first established composer to write film music (L'assassinat du duc de Guise, 1908), he did not succeed as well in the theatre as he did in the concert hall. Of his 13 operas (beginning with La princesse jaune, 1872, and including two commissioned by Monte Carlo), only Samson et Dalila remains in the repertory. Even this had a struggle to be heard at first, as impresarios fought shy of its biblical subject. Liszt encouraged him to finish it when they met at the Beethoven centenary celebrations, and he sponsored the première at Weimar in 1877 after delays caused by the Franco-Prussian War. Saint-Saëns restored Lully's music to Le Sicilien, ou L'amour peintre, staged at the Comédie Française in 1892, and Charpentier's music to Le malade imaginaire, performed at the Grand-Théâtre, Paris, later that year. He also completed his late friend Ernest Guiraud's opera Brunehilda, performed at the Opéra as Frédégonde in 1895.

Saint-Saëns was asked to assume the editorship of the complete works of Rameau for Durand in 1894, and in 1896 was invited to help Castelbon de Beauxhostes in his restoration of the Arènes de Béziers and to organize theatrical performances there. He composed incidental music for Louis Gallet's tragédie antique Déjanire, staged in 1898 with an orchestra that included the Garde Municipale of Barcelona, the Lyre Biterroise and 110 strings, 18 harps, 25 trumpets and choruses of more than 200; the audience of 10,000 came from all over France. In 1900 his cantata Le feu céleste, a celebration of electricity, opened the Exposition Universelle. Saint-Saëns was made a Grand Officier of the Légion d'Honneur in the same year, and was awarded the Cross of Merit by Emperor Wilhelm II; the following year he was named president of the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

He composed further incidental music, notably for Jane Dieulafoy's Parysatis at the Arènes de Béziers, where 450 instrumentalists and a chorus of 250 helped to evoke the oriental grandeur of the play. Sarah Bernhardt commissioned him to write incidental music for Racine’s Andromaque, and his comedies Le roi apépi and Botriocéphale were performed in Paris. He arranged a number of his works for different forces, and reworked his incidental music for Déjanire as an opera for Monte Carlo. Much of his time was spent in Egypt and Algeria, and during winter 1910–11 the Théâtre Municipal in Algiers staged five of his operas in succession. While he was in Cairo in 1913 he was awarded the Grande Croix of the Légion d'Honneur. He continued to travel, conducting, performing and supervising his own works, and spent four months visiting South America in 1916 despite fatigue and paralysis in his left hand.

He concluded his virtuoso career with a concert on 6 August 1921 at the Dieppe Casino, where he played seven pieces to mark the 75 years of his public performances as a pianist. At Béziers he closed his conducting career with rehearsals for Antigone on 21 August 1921. He returned to Algiers in December, and began some orchestration; he died later that month. His funeral took place at the cathedral, and his body was then taken to the Madeleine in Paris where he was given a state funeral. Although he seemed a reactionary to his younger colleagues, in his time Saint-Saëns served French music well. The perspective of history shows him as a neo-classicist and as the embodiment of certain traditional French qualities – moderation, logic, clarity, balance and precision – that were coming back into fashion at the turn of the 20th century.

Sabina Teller Ratner (with James Harding)

2. Works.

Saint-Saëns wrote in every 19th-century musical genre, but his most successful works are those based on traditional Viennese models, namely sonatas, chamber music, symphonies and concertos. Well schooled in the works of Bach and Beethoven, he was influenced at an early age by Mendelssohn and Schumann. His essentially Viennese upbringing was coloured by the French musical tradition of his day, and salon pieces, operas, and Spanish and exotic compositions survive in abundance. Moreover, his keen historical sense led him to revive many 17th-century French dance forms (bourrées, gavottes, menuets etc.), and his feelings of national loyalty are reflected in numerous marches and patriotic choruses. Towards the end of his life, he developed an austere style comparable to Fauré's. Throughout his career his art was one of amalgamation and adaptation rather than that of pursuing new and original paths; and this led Debussy to epitomize him as ‘the musician of tradition’. Saint-Saëns himself suggested: ‘I am an eclectic spirit. It may be a great defect, but I cannot change it: one cannot make over one's personality’.

Saint-Saëns's musical language is generally conservative. Although some of his melodies are supple and pliable, many are formal and rigid. They are usually built in well-defined phrases of three or four bars, and the phrase pattern AABB is characteristic. The most distinctive aspect of his music is his harmony, in which he was influenced by the theories of Gottfried Weber. Modulations by 3rds are typical, and while most chordal progressions are simple and direct, the many digressions and alterations lend nobility or charm to the music. He had a tendency to repeat rhythmic patterns, not only in his dance music, but as a general aspect of style or to create an exotic atmosphere. He preferred ordinary duple, triple or compound metres (3/4 is often designated as 3) and the use of unusual or free metres is rare (though a 5/4 passage occurs in the Piano Trio op.92 and one in 7/4 in the Polonaise for two pianos op.77). Cross-accents are frequent (the Second Symphony op.55 and the Second Violin Sonata op.102), as are changes of metre within a movement or phrase (First Violin Sonata op.75). Although he was a competent orchestrator, he achieved his sense of colour more by harmonic means than by purely orchestral effects. Throughout his career he was a master of counterpoint, which he learnt from Cherubini's manual in use at the Conservatoire. His mastery of this aspect of his art is evident in the fugues in his three sets of keyboard pieces (opp.99, 109, 161), but his contrapuntal craft is a general characteristic of his style and pervades most of his works. He adhered to traditional forms in his neo-classical and sonata-orientated compositions, but allowed himself more formal freedom in descriptive pieces.

Most of Saint-Saëns’s juvenile works remain unpublished, as do a great number of unfinished cantatas, choruses, songs and symphonies written before 1850. The most ambitious work of these early years was the Symphony in A (c1850). With the appearance of the Symphony no.1 (1853) and the Piano Quintet op.14 (?1855), Saint-Saëns entered a new phase of composition. These are serious and ambitious works written on a large scale, showing the influence of Schumann. The quintet is one of his earliest cyclic compositions and the piano writing is thick and heavy, a texture that is also in evidence in the ‘Urbs Roma’ Symphony and in those pieces from the period which combine piano and harmonium (e.g. op.8).

Not all the works written in the 1850s and 60s are so ponderous, however: the First Piano Trio op.18 has moments of extreme delicacy (the ostinato in the second movement is characteristic) and the Symphony no.2 is a prime example of orchestral economy, fugal severity and cyclic unity. The first three piano concertos (also from the 1850s and 60s) are notable as early examples of the piano concerto in France. The second, still in the repertory, has a first movement that deviates from the typical sonata-form pattern; all three have frivolous finales which capture the prevailing mood of the Second Empire. The First Cello Concerto op.33 is a far more serious work. Its stormy opening movement has an allegro appassionato character, more so than the two later works which actually bear this title (opp.43, 70). Saint-Saëns's op.28 willingness to experiment with the traditional form of the concerto is evident here and elsewhere, and his first works of descriptive music also date from the 1860s. In the Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso for violin and orchestra he used idiomatic Spanish rhythms, and in later works of this type (the Havanaise and Caprice andalous) he alternated raised and lowered 7ths to create a wistful mood. La princesse jaune, his first opera to be performed (1872), employs pentatonic melodies, used earlier in the march Orient et occident, and initiated a spate of operas on Japanese themes by other composers. His other exotic works (the Nuit persane, Suite algérienne, Africa, the Fifth Piano Concerto and Souvenir d'Ismaïlia) are frequently in the minor mode with the sixth and seventh degrees raised, also showing a variety of other techniques. The Rapsodie d'Auvergne and the Caprice sur des airs danois et russes are based on European folksongs, as are portions of several other works. Furthermore, the virtuoso pedal technique of his early organ works, such as the Fantaisie (1857) and the Trois rhapsodies sur des cantiques bretons (1866), is thought to have influenced the symphonic style of late 19th-century French organ writing. In the 1870s Saint-Saëns composed four symphonic poems (Le rouet d'Omphale, Phaéton, Danse macabre and La jeunesse d'Hercule) in which he experimented with orchestration and thematic transformation. La jeunesse d'Hercule is modelled closely on Liszt, but the others concentrate on some physical movement – spinning, riding, dancing – which is described in musical terms. He had previously experimented with thematic transformation in his programmatic overture Spartacus and later used it in his Fourth Piano Concerto and the ‘Organ’ Symphony (no.3).

Some of Saint-Saëns’s best and most characteristic compositions date from the 1870s and 80s. These include the Fourth Piano Concerto, Third Violin Concerto, ‘Organ’ Symphony, Samson et Dalila, Le déluge, the Piano Quartet op.41, the First Violin Sonata, First Cello Sonata, Variations on a Theme of Beethoven and Le carnaval des animaux. Characteristic of many works written at this time is the use of repeated rhythmic motifs or of chorale melodies, combined in the second movement of the op.41 quartet. Both the Fourth Piano Concerto and the ‘Organ’ Symphony begin in C minor and end in C major employ thematic transformation and a chorale melody, and the four movements are arranged (as are those of the First Violin Sonata) in an interlocking pattern of two plus two. Saint-Saëns worked on Le carnaval des animaux concurrently with the ‘Organ’ Symphony and it remains his most brilliant comic work, parodying Offenbach, Berlioz, Mendelssohn, Rossini, his own Danse macabre and several popular tunes. The Third Violin Concerto (1880) is more rewarding musically and less demanding technically than the two earlier violin concertos; the chorale-like passage in B major near the end may have been influenced by his own Fourth Piano Concerto. A Morceau de concert for violin, written in the same year as the concerto, shares a number of affinities with it. Unlike his other Morceaux de concert (opp.94, 154), this piece is essentially a concerto first movement.

Samson (Jean-Alexandre Talazac) brings down the Temple of Dagon at the end of Act 3 of the first Paris production of Saint-Saëns’s ‘Samson et Dalila’, Eden-Théâtre, 31 October 1890: engraving from ‘L’illustration’ (8 November 1890)

Mary Evans Picture Library, London

As an opera composer Saint-Saëns had an unerring sense for accurate declamation; in Samson et Dalila he also retained the identity of aria and ensemble, welding the whole work together with solid musical craftsmanship. Among his other operas, Etienne Marcel, Henry VIII (which has a principal theme based on a traditional English melody that Saint-Saëns found in the Buckingham Palace library) and Ascanio merit study and revival. The subjects he chose call for the flamboyant expertise of a Meyerbeer, and although the operas contain much agreeable and skilfully shaped music, they are deficient in theatrical effect. The success of Samson et Dalila can be attributed not least to its having originally been conceived as an oratorio, thereby enabling the composer to concentrate on purely musical aspects.

Saint-Saëns wrote songs throughout his career, setting the poetry of Lamartine, Hugo and Banville as well as his own verses. The style naturally varies with the subject, but many songs reveal his vivid pictorial sense and his gift for caricature.

Much of Saint-Saëns's piano music was written after 1870. Most of it is salon music (mazurkas, waltzes, albumleaves, souvenirs etc.); but the three sets of Etudes (opp.52, 111, 135) and the Variations on a Theme of Beethoven op.35 (piano duo) rank with the concertos. The Septet op.65 (1880) is, like the suites (opp.16, 49, 90), a neo-classical work that revives 17th-century French dance forms. Although these dances are rigid and less original than the pavanes and menuets antiques of Debussy and Ravel, they reflect Saint-Saëns's interest in the rediscovery and revival of the forgotten French musical tradition of the 17th century (his editions of Lully, Charpentier and Rameau date from this period).

Beginning with the Second Violin Sonata (1896), a stylistic change is noticeable in much of Saint-Saëns's music. The piano writing is generally more linear and less heavy, and there is a growing preference for the thin sonorities of the harp (as in the Fantaisie op.95 for harp, the Fantaisie op.124 for violin and harp and the Morceau de concert op.154 for harp and orchestra) and woodwind (as in Odelette op.162 for flute and orchestra and the solo sonatas for oboe, clarinet and bassoon opp.166–8). The two string quartets (opp.112, 153) mark the first elimination of the piano in his chamber works. Remote chord progressions and modal cadences become increasingly apparent, and the subjects of his stage works are almost exclusively Greek. This austere tendency is, of course, typical of many composers after World War I, but it serves to emphasize the classical aspect of Saint-Saëns's nature which, latent earlier, had seldom been displayed in such rarefied form. Saint-Saëns's oeuvre has been criticized as uneven; this is in part the result of both an unusual facility and his friendship with the publisher Auguste Durand, who was perhaps insufficiently critical. However, it is also diverse and multi-faceted.

Saint-Saëns's writings attest his wide tolerance on many musical issues and his concern for order, clarity and precision. Like the Parnassian poets, he was a proponent of ‘art for art's sake’, and his views on expression and passion in art conflicted with the prevailing Romantic aesthetic. In his memoirs, Ecole buissonnière, he wrote: "Music is something besides a source of sensuous pleasure and keen emotion, and this resource, precious as it is, is only a chance corner in the wide realm of musical art. He who does not get absolute pleasure from a simple series of well-constructed chords, beautiful only in their arrangement, is not really fond of music."

Although Saint-Saëns’s writings are remarkably consistent, it cannot be said that he evolved a distinctive musical style. Rather, he defended the French tradition that threatened to be engulfed by Wagnerian influences and created the environment that nourished his successors.

Daniel M. Fallon/Sabina Teller Ratner

Grove Music online accessed 10/23/2017

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Hamburg, Germany, 1809 - 1847, Leipzig, Germany

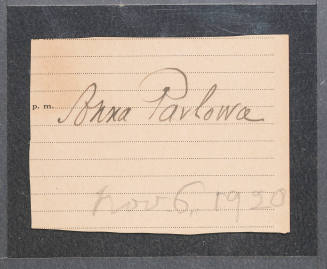

St. Petersburg, 1881 - 1931, Hague, Netherlands