David Bispham

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1857 - 1921, New York, New York

In 1886 he ventured to Europe, studying voice for three years in Florence and Milan. In 1890 he settled in London, studying acting as well as singing in amateur performances. On 24 June 1892 his "big break" came when he successfully auditioned for the role of Kurwenal in Wagner's Tristan und Isolde at London's new Drury Lane Theatre; the conductor was composer Gustav Mahler. Bispham's success under Mahler's baton won him the notice of critics and other conductors and managers in London.

In 1896 Bispham became a lead baritone at Covent Garden in London and at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, and soon established himself as one of the leading baritones of the operatic world. He was celebrated particularly for his Wagnerian roles. A certain nasal character in Bispham's voice enhanced the effectiveness of some of his Wagnerian portrayals, particularly those of Kurwenal in Tristan and, even more, of Beckmesser in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, where the comic features of the role could thus be subtly underscored. Bispham himself boasted that his Beckmesser and Kurwenal were the greatest of their day.

Bispham was the first American-born opera singer to attain world stature. Critics in America and Europe commented upon both the rich resonances in the lower registers of Bispham's voice and the sophisticated level of acting he brought to the operatic stage--a dimension often missing among singers. Indeed, toward the end of his life, his voice having lost much of its strength, Bispham could still fill concert halls doing dramatic readings. Bispham once performed at the White House, and President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) exclaimed to him: "By jove, Mr. Bispham, that was bully! With such a song as that you could lead a nation into battle."

In 1903 Bispham retired from regular operatic performing and turned to song recitals. He was equally successful here with both audiences and critics. His entry into this musical genre coincided with the birth of the recording industry, and Bispham was among the first to record many of the famous German lieder. His recording of Schubert's Erl König, set to Goethe's text, with its dramatic interplay of four characters, remains gripping despite the hissing and tinniness typical of early recordings. Bispham was the first major singer to perform the famous vocal literature of Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann and others in English. He also took part in English-language stagings of Mozart operas. With Bispham performing, critics could not summarily dismiss such presentations.

Bispham was critical of arts benefactors, such as Andrew Carnegie and J. P. Morgan (1837-1913), "who now direct the dramatic destinies of America [and fund] the masterpieces of other countries." Advocating a loosening of this tradition in order to promote national traditions, Bispham rejected the idea that the English language could not support serious art. "There is nothing bad in English," he declared, "as a medium for opera and song, except bad English." While nationalistic, Bispham remained openly elitist regarding the availability of musical training. Addressing a group of music teachers, he asserted that "no one should retain pupils who are not good enough at least to become fairly good amateurs." "How are we then to earn a living?" asked one. Bispham snorted: "Do something else."

Bispham's enthusiasm for English-language productions prompted the formation of the Society of American Singers, which continued the campaign for such work in art song and opera. The Opera Society of America, a Chicago-based organization, also promoted English productions. The Society regularly gives an award for excellence in American music making, an award fittingly named the David Bispham Medal. Bispham died in New York City.

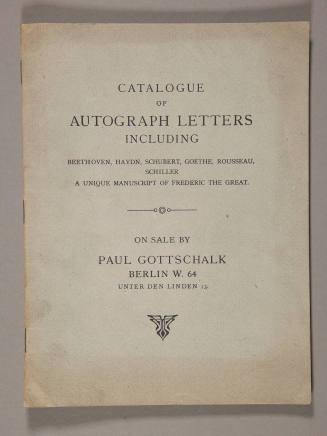

Bibliography

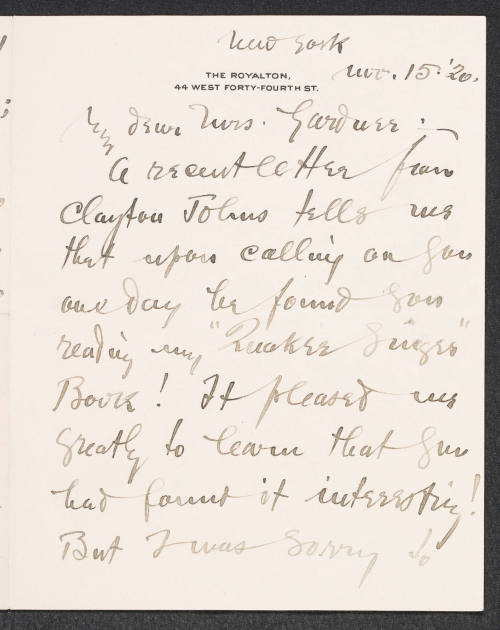

David Bispham's autobiography is A Quaker Singer's Recollections (1920). An informative entry on his career appears in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (1980).

Alan H. Levy

Citation:

Alan H. Levy. "Bispham, David Scull";

http://www.anb.org/articles/18/18-00109.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 10:38:40 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Newton, Massachusetts, 1871 - 1940, Westwood, Massachusetts

Bonn, Germany, 1770 - 1827, Vienna

La Côte-Saint-André, France, 1803 - 1869, Paris