Alfred Tennyson

Somersby, 1809 - 1892, Haslemere

LC name authority rec.

LC Heading: Tennyson, Alfred Tennyson, Baron, 1809-1892

Biography:

Tennyson, Alfred, first Baron Tennyson (1809–1892), poet, was born on 6 August 1809 at Somersby rectory, Lincolnshire, the fourth child (there were to be eight sons and four daughters in fourteen years) of the Revd Dr George Clayton Tennyson (1778–1831), rector of Somersby, and his wife, Elizabeth (bap. 1780, d. 1865), daughter of the Revd Stephen Fytche, vicar of Louth, Lincolnshire.

The family

Tennyson's father, though not strictly disinherited, had been reduced in favour and fortune much below his younger brother, and Tennyson's youth was overshadowed by this family feud between the Tennysons of Somersby and the grandparents, of Bayons Manor (16 miles away), with their favoured son (later Charles Tennyson-D'Eyncourt; 1784–1861). Tennyson's wife, Emily, was to write, in her reminiscences for her two sons, of this ‘caprice on the part of your great-grandfather’, whereby Dr Tennyson

was deprived of a station which he would so greatly have adorned and put into the Church for whose duties he felt no call. This preyed upon his nerves and his health and caused much sorrow in his house. Many a time has your father [the poet] gone out in the dark and cast himself on a grave in the little churchyard near wishing to be beneath it.(Lincoln MS; compare H. Tennyson, Memoir, 1.15)

The black blood of the Tennysons was all too familiar. The oldest surviving brother (George had died in infancy) was Frederick Tennyson (1807–1898); irascible, he was to live, mostly in Italy, in expatriate eccentricity. The next senior was Charles (later, from 1835, as the condition of an uncle's bequest, Charles Turner, often known as Charles Tennyson Turner (1808–1879), an exquisite poet, praised by Coleridge); he was for many years addicted to opium and vulnerable to alcohol (it was long before he arrived at his serenity). A younger brother, Edward, succumbed in 1832 to insanity, which proved incurable throughout his long life (he died in 1890, only two years before his famous brother). Arthur for a while in the 1840s collapsed into alcoholism. Then there was the brother who rose from the hearthrug and introduced himself, ‘I am Septimus, the most morbid of the Tennysons’ (C. Tennyson, Alfred Tennyson, 199). Of him, Tennyson wrote to his uncle Charles in 1834:

At present his symptoms are not unlike those with which poor Edward's unhappy derangement began—he is subject to fits of the most gloomy despondency accompanied with tears—or rather, he spends whole days in this manner, complaining that he is neglected by all his relations, and blindly resigning himself to every morbid influence. (Received 15 Jan 1834, Letters, 1.106)

Morbid influence, not blindly resigned to but contemplated with creative courage, informs much of Tennyson's deepest work, unhappiness current or unforgettable, misery unutterable that yet found itself uttered.

In my youth I knew much greater unhappiness than I have known in later life. When I was about twenty, I used to feel moods of misery unutterable! I remember once in London the realization coming over me, of the whole of its inhabitants lying horizontal a hundred years hence. The smallness and emptiness of life sometimes overwhelmed me.(Lincoln MS, ‘Talks and Walks’; H. Tennyson, Memoir, 1.40)

Schooling, juvenilia, and Lincolnshire

In 1815 Tennyson left the village school and—staying with his grandmother in Louth—became a pupil at Louth grammar school, where his elder brothers Frederick and Charles had started in 1814. Tennyson: ‘How I did hate that school! The only good I ever got from it was the memory of the words, “sonus desilientis aquae”, and of an old wall covered with wild weeds opposite the school windows’ (H. Tennyson, Memoir, 1.7). In 1820 he left Louth, to be educated at home by his learned, violent, and often drunken father—who believed in him. ‘My father who was a sort of Poet himself thought so highly of my first essay that he prophesied I should be the greatest Poet of the Time’ (Trinity Notebook, 34).

Tennyson was to recall ruefully his youthful ambitions and poetical models. It was the mouthability of poetry, the urge to roll it aloud, that drew him.

The first poetry that moved me was my own at five years old. When I was eight, I remember making a line I thought grander than Campbell, or Byron, or Scott. I rolled it out, it was this: ‘With slaughterous sons of thunder rolled the flood’—great nonsense of course, but I thought it fine. (H. Tennyson, Memoir, 2.93)

He was much moved by the death of Byron in 1824: ‘I was fourteen when I heard of his death. It seemed an awful calamity; I remember I rushed out of doors, sat down by myself, shouted aloud, and wrote on the sandstone: “Byron is dead!”’ (ibid., 69).

Before I could read, I was in the habit on a stormy day of spreading my arms to the wind, and crying out ‘I hear a voice that's speaking in the wind’, and the words ‘far, far away’ had always a strange charm for me.

Tennyson spoke of the three-book epic (‘à la Scott’) written in his ‘very earliest teens’. ‘I never felt so inspired—I used to compose 60 or 70 lines in a breath. I used to shout them about the silent fields, leaping over the hedges in my excitement’ (Trinity Notebook, 34; H. Tennyson, Memoir, 1.11–12).

Tennyson's prodigious excitement is evidenced in the play he wrote (1823–4) in imitation of Elizabethan comedy, The Devil and the Lady, a wondrous pastiche, alive in its ambivalent erotic deploring, its vistas of space, its anatomizing of old age, and its grim humour. Duller, placatingly conventional, there was published in April 1827, by J. and J. Jackson, booksellers of Louth, Poems by Two Brothers (three brothers, since Frederick supplied four poems for this volume by Charles and Alfred); it earned them £20 (more than half in books) and courteous flat notices in the Literary Chronicle (19 May 1827) and the Gentleman's Magazine (June). Tennyson's unoriginal contributions were written ‘between 15 and 17’ (1893 reissue of 1827, quoting Tennyson). Wisely, he did not include any of them in later editions of his works.

But the Lincolnshire of Tennyson's young days was alive in his late poems, notably those in dialect, ‘wonderful studies in English vernacular life’ as Richard Holt Hutton called them (Hutton, 380). Tennyson's gruff gnarled humour here found its local habitation and intonation, audible in his own recorded reading of the best of them, ‘Northern Farmer: New Style’, ‘founded’, as Tennyson said, on a single sentence: ‘When I canters my 'erse along the ramper [highway] I 'ears “proputty, proputty, proputty”’ (Poems, 2.688).

Cambridge, Arthur Hallam, and early accomplishments

In November 1827 Tennyson entered Trinity College, Cambridge, where Charles had just joined Frederick. He was unhappy there at first (and often subsequently—see the bitter sonnet that he chose not to publish, ‘Lines on Cambridge of 1830’): ‘The country is so disgustingly level, the revelry of the place so monotonous, the studies of the University so uninteresting, so much matter of fact—none but dryheaded calculating angular little gentlemen can take much delight’ in algebraic formulae (18 April 1828, Letters, 1.23). But fortunately he came to know some well-rounded larger gentlemen, foremost among them Arthur Henry Hallam (1811–1833) [see under Hallam, Henry (1777–1859)], whom Tennyson met about April 1829. Hallam had entered Trinity College the previous October. The friendship, deepening into love, of Hallam and Tennyson was to be one of the most important experiences of Hallam's short life and of Tennyson's long one.

A further flowering at Cambridge: in October 1829 Tennyson was elected a member of the Apostles, an informal debating society to which most of his Cambridge friends belonged (such eminent, though not pre-eminent, Victorians as John Kemble, Richard Chenevix Trench, Richard Monckton Milnes, and James Spedding). Then in June 1829 he won the chancellor's gold medal with his prize poem on the set subject Timbuctoo. Reworking an earlier poem (as he was so often to do with consummate re-creative imagination), this on Armageddon, ‘altering the beginning and the end’ to bend it on Timbuctoo, ‘I was never so surprised as when I got the prize’ (Lincoln MS, ‘Materials for a Life of A. T.’; H. Tennyson, Memoir, 2.355). The surprise was the greater in that the winning poem was, unprecedentedly, not in heroic couplets but in blank verse. At the heart of the poem is a mystical trance such as fascinated Tennyson lifelong. Hallam, happily worsted, wrote with characteristic generosity and acumen: ‘The splendid imaginative power that pervades it will be seen through all hindrances. I consider Tennyson as promising fair to be the greatest poet of our generation, perhaps of our century’ (A. H. Hallam to Gladstone, 14 Sept 1829, Letters of Arthur Henry Hallam, 319).

Then in December 1829 (or, it may be, April 1830), Hallam met Tennyson's sister Emily, with whom he was soon to fall in love. In the summer of 1830 Tennyson visited the Pyrenees with Hallam. (More than thirty years later, in June 1861, Tennyson was to return there with his family and to write ‘In the Valley of Cauteretz’, in lasting love of Hallam.) Hallam and Tennyson were to visit the Rhine country in the summer of 1832. In the autumn of 1832 the engagement of Hallam to Tennyson's sister was to be reluctantly recognized by Hallam's family.

Poems, Chiefly Lyrical was published by Effingham Wilson in June 1830; some of Tennyson's most enduring notes, elegiacally lyrical, with his riven sensibility (‘Supposed Confessions of a Second-Rate Sensitive Mind Not at Unity with Itself’), are especially manifest in the volume's most remarkable achievements, ‘Mariana’, ‘A spirit haunts the year's last hours’, and ‘The Kraken’.

Tennyson's father, after marital separation and then a return to protracted illness and weakness, died in March 1831. Tennyson left Cambridge without taking a degree. His choice of life? His uncle Charles wrote on 18 May 1831 to Tennyson's grandfather, the Old Man of the Wolds:

We discussed what was to be done with the Children. Alfred is at home, but wishes to return to Cambridge to take a degree. I told him it was a useless expense unless he meant to go into the Church. He said he would. I did not think he seemed much to like it. I then suggested Physic or some other Profession. He seemed to think the Church the best and has I think finally made up his mind to it. The Tealby Living was mentioned and understood to be intended for him.

Then, reverting to the matter: ‘Alfred seems quite ready to go into the Church although I think his mind is fixed on the idea of deriving his great distinction and greatest means from the exercise of his poetic talents’ (Letters, 1.59–61).

Poetic talents needed the support of financial talents. Fortunately, from his aunt Russell he received £100 a year (this continued into the 1850s), and when his grandfather died in 1835, there came to Tennyson about £6000. Even though most of this was lost in a bad investment, there was to be the civil-list pension of £200 a year that began in 1845 (he drew it until he died), and his straits were never as dire as he liked to maintain.

The poetic talents were Arthur Hallam's focus in the Englishman's Magazine, in August 1831: ‘On Some of the Characteristics of Modern Poetry, and on the Lyrical Poems of Alfred Tennyson’. W. B. Yeats was to praise this essay as

criticism which is of the best and rarest sort. If one set aside Shelley's essay on poetry and Browning's essay on Shelley, one does not know where to turn in modern English criticism for anything so philosophic—anything so fundamental and radical—as the first half

of Hallam's piece (The Speaker, 22 July 1893; Yeats, 277). Of Tennyson's art, Hallam's essay remains the most compactly telling evocation, prescient too. Hallam limned five characteristics:

First, his luxuriance of imagination, and at the same time his control over it. Secondly his power of embodying himself in ideal characters, or rather moods of character, with such extreme accuracy of adjustment, that the circumstances of the narration seem to have a natural correspondence with the predominant feeling, and, as it were, to be evolved from it by assimilative force. Thirdly his vivid, picturesque delineation of objects, and the peculiar skill with which he holds all of them fused, to borrow a metaphor from science, in a medium of strong emotion. Fourthly, the variety of his lyrical measures, and exquisite modulation of harmonious words and cadences to the swell and fall of the feelings expressed. Fifthly, the elevated habits of thought, implied in these compositions, and imparting a mellow soberness of tone, more impressive, to our minds, than if the author had drawn up a set of opinions in verse, and sought to instruct the understanding rather than to communicate the love of beauty to the heart. (Jump, 42)

Hallam's acute praise was welcome but not to everybody—Tennyson was already becoming ‘the Pet of a Coterie’, according to Christopher North (John Wilson) in Blackwood's Magazine in May 1832 (Jump, 50). In February 1832 the notoriously scathing Christopher North had praised Tennyson highly, albeit with caveats, in Blackwood's, but then in May he followed this with a wittily severe—not indiscriminate—review of the 1830 volume, this to ‘save him from his worst enemies, his friends’ (Jump, 51). Tennyson, pricked though not bridled by such reviewers, was exacerbatedly thin-skinned and always self-critical, often revising talent into genius—or expunging: the volume of 1830 included twenty-three poems that he did not subsequently reprint, as well as seven not collected in his two-volume Poems (1842) though reprinted later. The poems of 1830 that he did reprint, he—unusually—grouped as ‘Juvenilia’, justly in some cases, unjustly (protectively) for such a great poem as ‘Mariana’.

Fertile, Tennyson issued in December 1832 Poems (published by Edward Moxon, the title-page dated 1833). Among its feats were ‘The Lady of Shalott’, ‘Mariana in the South’, ‘Œnone’, ‘The Palace of Art’, ‘The Lotos-Eaters’, and ‘A Dream of Fair Women’. There were some failures subsequently acknowledged: seven poems never reprinted, and seven not collected in Poems (1842) though reprinted later. A venomous review by J. W. Croker (Quarterly Review, April 1833) drew blood but was a spur: the best of the poems were to be made even better, duly revised for republication, ten years later, but the painful rewording process began at once. As his Cambridge friend Edward FitzGerald wrote on 25 October 1833:

Tennyson has been in town for some time: he has been making fresh poems, which are finer, they say, than any he has done. But I believe he is chiefly meditating on the purging and subliming of what he has already done: and repents that he has published at all yet. It is fine to see how in each succeeding poem the smaller ornaments and fancies drop away, and leave the grand ideas single. (Letters of Edward FitzGerald, 1.140)

It is heartening that in October 1833 Tennyson could be so actively creative in new and newly improved poems. For it was on 1 October that there was sent to him the news of the sudden death of Arthur Hallam, stricken on 15 September by apoplexy while visiting Vienna. His body was brought back by sea to Clevedon, on the Bristol Channel, ‘Among familiar names to rest’, ‘And in the hearing of the wave’ (In Memoriam, XVIII and XIX).

The blow, not to Tennyson alone, but to his sister Emily, to both families, and to Hallam's many friends and admirers, was profound, ‘a loud and terrible stroke’ (reported the Cambridge friend Charles Merivale) ‘from the reality of things upon the faery building of our youth’ (from H. Alford, 11 Nov 1833, Merivale, 135). The sense of the Tennyson family loss is audible in a letter by Frederick of 18 December 1833:

We all looked forward to his society and support through life in sorrow and in joy, with the fondest hopes, for never was there a human being better calculated to sympathize with and make allowance for those peculiarities of temperament and those failings to which we are liable. (Letters, 1.104)

Yet in the first stricken month, Tennyson set to write poems that later became some of the finest sections of In Memoriam (the earliest is dated 6 October 1833, none being published until seventeen years after Hallam's death), as well as soon drafting ‘Ulysses’, ‘Morte d'Arthur’, and ‘Tithonus’ (this last not published until 1860, the other two 1842)—three great poems prompted by the death of his Arthur, and all finding extraordinarily compelling correlatives, in ancient worlds, for his feelings personal and universal, ancient and modern.

‘The Two Voices’ belongs to 1833, and was said by Tennyson's son to have been ‘begun under the cloud of this overwhelming sorrow, which, as my father told me, for a while blotted out all joy from his life, and made him long for death’ (H. Tennyson, Memoir, 1.109). But Tennyson had longed for death before Hallam died, and a draft of ‘The Two Voices’ was in existence three months earlier, in June 1833, when his friend J. M. Kemble wrote to W. B. Donne:

Next Sir are some superb meditations on Self destruction called Thoughts of a Suicide wherein he argues the point with his soul and is thoroughly floored. These are amazingly fine and deep, and show a mighty stride in intellect since the Second-Rate Sensitive Mind. (Poems, 1.570)

Suicide appears, often enacted and sometimes discussed, in an extraordinary number of Tennyson's poems over the years, where it is complemented not only by suicidal risks but by martyrs and by the military (as in ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’). Mary Gladstone was to record ‘a plan he had of writing a satire called “A suicide supper”’, and that Tennyson ‘would commit suicide’ if he believed that death were annihilation (Mary Gladstone, 8 June 1879, 160).

On 14 February 1834 Tennyson replied to a request from Hallam's father to contribute to a memorial volume:

I attempted to draw up a memoir of his life and character, but I failed to do him justice. I failed even to please myself. I could scarcely have pleased you. I hope to be able at a future period to concentrate whatever powers I may possess on the construction of some tribute to those high speculative endowments and comprehensive sympathies which I ever loved to contemplate; but at present, though somewhat ashamed at my own weakness, I find the object yet is too near me to permit of any very accurate delineation. You, with your clear insight into human nature, may perhaps not wonder that in the dearest service I could have been employed in, I should be found most deficient. (Letters, 1.108)

In Memoriam A.H.H. (1850) was duly to render such dearest service—to Hallam, to Tennyson himself, and to all his readers then and since, to all those who, like Queen Victoria and whatever their beliefs, have found, in its mourning and in its recovery, lasting consolation.

Tennyson, afraid (with good cause) of the spite which—like Keats before him, and similarly with some class animus—he precipitated in reviewers, tried in 1834 to placate Christopher North, and tried in early March 1835 to discourage John Stuart Mill from writing about the poems.

I do not wish to be dragged forward again in any shape before the reading public at present, particularly on the score of my old poems most of which I have so corrected (particularly Œnone) as to make them much less imperfect. (To James Spedding, Letters, 1.130)

Fortunately, Mill went ahead, and discerningly praised in Tennyson

the power of creating scenery, in keeping with some state of human feeling; so fitted to it as to be the embodied symbol of it, and to summon up the state of feeling itself, with a force not to be surpassed by anything but reality.(London Review, July 1835; Jump, 86)

Love, marriage, and lifelong faith

It was in 1834 that Tennyson fell in love with Rosa Baring, of Harington Hall, 2 miles from Somersby. It was to be a brief and frustrated love (she was rich, she was a Baring, she was—it seems—a coquette), but it was never to fade from his memory. It was less the joys of this young romance than the pains of disillusionment, following promptly in 1835–6, that had a lastingly valuable presence within his writing, for the pressures of social snobbery—long known from the Tennyson v. Tennyson-D'Eyncourt feud—and of ‘The rentroll Cupid of our rainy isles’ (‘Edwin Morris’), ‘This filthy marriage-hindering Mammon’ (‘Aylmer's Field’), are acidly etched in ‘Locksley Hall’, ‘Edwin Morris’, and Maud, all written or inaugurated between 1837 and 1839. Tennyson was the better able to gauge this amatory excitement of his because of his soon coming to love, deeply, Emily Sellwood [see Tennyson, Emily Sarah (1813–1896)]. He had first met her in 1830, the daughter of a solicitor in Horncastle (5 miles from Somersby). In May 1836 Emily's sister Louisa married Tennyson's older brother Charles (now curate of Tealby in Lincolnshire), and Tennyson was to date his love for Emily from this wedding, where he glimpsed the happy bridesmaid as his future happy bride. In 1838 the engagement was recognized by her family and his, but was broken off in 1840, partly because of financial insecurity (‘owing to want of funds’, their son was to write (H. Tennyson, Memoir, 1.150)), but also because of Tennyson's religious unorthodoxy and spiritual perturbation. It was not until 1849 that his correspondence with Emily was renewed. Then the honest faith and the honest doubt evinced within In Memoriam (to be published in May 1850) played a large part in overcoming Emily's doubts, and she and the poet were wed on 13 June 1850. The service was at Shiplake-on-Thames where Tennyson's friend Drummond Rawnsley was vicar.

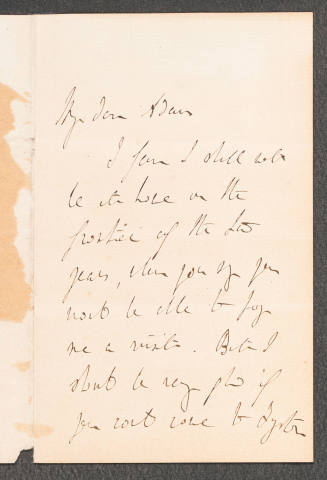

This was to be a happy marriage, clearly seen in ‘The Daisy’, about Tennyson's visit to Italy with Emily in 1851 (a delayed honeymoon), and in the lovely late tribute, ‘June Bracken and Heather’, written in 1891, the year before he died, and constituting the dedication of his final and posthumous volume. Equably hierarchical and reciprocally loving, warmly embracing the double duty of family claims and the claims of art, their life together was a joy. It was sadly darkened by the stillbirth of their first child on 20 April 1851, and by the grievous loss of their son Lionel (b. 16 March 1854), dead in his thirties (April 1886), but it was blessed with the lifelong self-abnegating dedication of their son Hallam Tennyson (1852–1928). Their home was at first Chapel House, Montpelier Row, Twickenham. In November 1853 they moved to Farringford (Freshwater, Isle of Wight), which Tennyson bought in 1856. Among the many notable visitors to Farringford was Garibaldi, in April 1864. In April 1868 the foundation stone was laid of Tennyson's second home, Aldworth, near Haslemere.

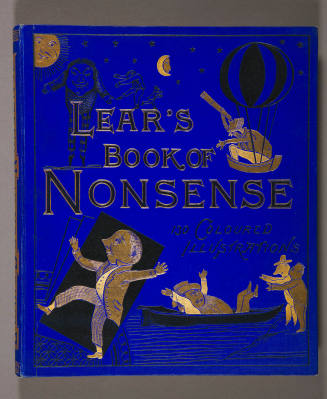

Emily Tennyson was judged incomparable by Edward Lear:

I should think, computing moderately, that 15 angels, several hundreds of ordinary women, many philosophers, a heap of truly wise & kind mothers, 3 or 4 minor prophets, & a lot of doctors and school-mistresses, might all be boiled down, & yet their combined essence fall short of what Emily Tennyson really is. (2 June 1859, Noakes, 167)

More two-edgedly, FitzGerald granted that she was

a Lady of a Shakespearian type, as I think AT once said of her: that is, of the Imogen sort, far more agreeable to me than the sharp-witted Beatrices, Rosalinds, etc. I do not think she has been (on this very account perhaps) as good a helpmate to AT's Poetry as to himself. (7 Dec 1869, Letters of Edward FitzGerald, 3.177)

Benjamin Jowett praised her: ‘overflowing with kindness—but also in a certain way very strong’, ‘his friend, his servant, his guide, his critic’. ‘It was a wonderful life—an effaced life like that of so many women’ (Harvard MS, Catalogue, 19–20). ‘One of the most beautiful, the purest, the most innocent, the most disinterested persons whom I have ever known’: ‘she was probably her husband's best critic, and certainly the one whose authority he would most willingly have recognized’ (H. Tennyson, Memoir, 2.466–7).

His wife was of unique importance to Tennyson's religious self. She trusted Charles Kingsley, who in September 1850 described In Memoriam as

altogether rivalling the sonnets of Shakespeare.—Why should we not say boldly, surpassing—for the sake of the superior faith into which it rises, for the sake of the proem at the opening of the volume—in our eyes, the noblest English Christian poem which several centuries have seen?(Fraser's Magazine; Jump, 183)

Aubrey de Vere characterized Emily, a few months after the marriage:

Her great and constant desire is to make her husband more religious, or at least to conduce, as far as she may, to his growth in the spiritual life. In this she will doubtless succeed, for piety like hers is infectious, especially where there is an atmosphere of affection to serve as a conducting medium. Indeed I already observe a great improvement in Alfred. His nature is a religious one, and he is remarkably free from vanity and sciolism. Such a nature gravitates towards Christianity, especially when it is in harmony with itself. (14 Oct 1850, Ward, 158–9)

Gruffer, there are Tennyson's words to Gladstone's daughter Mary (4 June 1879): ‘We shall all turn into pigs if we lose Christianity and God’ (Mary Gladstone, 157). ‘T. loves the spirit of Christianity, hates many of the dogmas’, reported William Allingham in January 1867 (Allingham, 149). He respected the breadth and latitude of F. D. Maurice. In October 1853 Maurice was forced to resign from his professorship in London for arguing that the popular belief in the endlessness of future punishment was superstitious. Tennyson abominated the belief in eternal torment, and he had recently asked Maurice (who had agreed) to be godfather to Hallam Tennyson. ‘To the Rev. F. D. Maurice’ is a verse invitation that glowingly revives the Horatian epistle, and bears comparison with such classics of the kind as Ben Jonson's ‘Inviting a Friend to Supper’.

In April 1869 Tennyson attended the meeting to organize the Metaphysical Society, which he joined and which flourished until 1879. In his seventies he said to Allingham, in July 1884: ‘You're not orthodox, and I can't call myself orthodox. Two things however I have always been firmly convinced of—God,—and that death will not end my existence’ (Allingham, 329). The very late poems, ‘The Ancient Sage’ (1885), on Lao-Tse, and ‘Akbar's Dream’ (1892), on what was then called Mohammedanism, seek to realize—under the influence of Benjamin Jowett—‘The religions of all good men’, in support of the conviction that ‘All religions are one’.

Two months before he died, Tennyson talked with John Addington Symonds:

He told me he was going to write a poem on Bruno, and asked what I thought about his [Bruno's] attitude toward Christianity. I tried to express my views, and Hallam got up and showed me that they were reading up the chapter of my ‘Renaissance in Italy’ on Bruno. Tennyson observed that the great thing in Bruno was his perception of an Infinite Universe, filled with solar systems like our own, and all penetrated with the Soul of God. ‘That conception must react destructively on Christianity—I mean its creed and dogma—its morality will always remain.’ Somebody had told him that astronomers could count 550 million solar systems. He observed that there was no reason why each should not have planets peopled with living and intelligent beings. ‘Then,’ he added, ‘see what becomes of the second person of the Deity, and the sacrifice of a God for fallen man upon this little earth!’ (29 Aug 1892, Letters of John Addington Symonds, 3.744)

From Poems (1842) to The Princess (1847)

Between 1832 and 1842 Tennyson published no volume-length work. The span has been mildly melodramatized into ‘the ten years' silence’, but he wrote much during this period, founding and building In Memoriam, creating his exquisite ‘English Idyls’ (most notably, ‘Edwin Morris’ and ‘The Golden Year’), and he rewrote with depth and passion. At the urging of his friend Richard Monckton Milnes, he reluctantly sent to The Tribute (September 1837) a true though as yet unperfected poem, ‘Oh! that 'twere possible’, which was to be ‘the germ’ of the amazing monodrama of madness, Maud (1855).

Life was taxing. On the death of Dr Tennyson in 1831 the family had been allowed by the incoming rector to continue to live in the rectory at Somersby, but then, in 1837, they had to move to High Beech, Epping Forest. ‘His two elder brothers being away’ (Frederick in Corfu and then Florence—for good; and Charles settled at Grasby, Lincolnshire), it was on Alfred that there ‘devolved the care of the family and of choosing a new home’ (H. Tennyson, Memoir, 1.149–50; ‘My mother is afraid if I go to town even for a night; how could they get on without me for months?’, to Emily Sellwood, 10 July 1839, Letters, 1.171). Then in 1840 they had to move to Tunbridge Wells, and in 1841 to Boxley, near Maidstone. The engagement to Emily Sellwood was broken off in 1840. Then there was the investing by Tennyson in 1840–41 of his invaluable small fortune (about £3000) in a scheme for wood-carving by machinery, which had collapsed by 1843. These were among the things that made much of life a misery. ‘I have drunk one of those most bitter draughts out of the cup of life, which go near to make men hate the world they move in’ (H. Tennyson, Memoir, 1.221). FitzGerald reported of Tennyson, to Tennyson's brother Frederick, on 10 December 1843 that he had ‘never seen him so hopeless’ (Letters of Edward FitzGerald, 1.408). In 1843–4 Tennyson received treatment.

The perpetual panic and horror of the last two years has steeped my nerves in poison: now I am left a beggar but I am or shall be shortly somewhat better off in nerves. I am in a Hydropathy Establishment near Cheltenham (the only one in England conducted on pure Priessnitzan principles) ... Much poison has come out of me, which no physic ever would have brought to light. (To FitzGerald, 2 Feb 1844, Letters, 1.222–3)

The hydropathy was endured near Cheltenham; Tennyson then lived, first, at 6 Bellevue Place, and then at 10 St James's Square, Cheltenham.

In an unpublished poem (‘Wherefore, in these dark ages of the Press’), Tennyson spoke of ‘this Art-Conscience’, a surety which, along with courage, steadied and secured him. This, with more than a little help from his friends, who encouraged him, pressed him. On 3 March 1838: ‘Do you ever see Tennyson? and if so, could you not urge him to take the field?’ (R. C. Trench to R. M. Milnes, Reid, 1.208). ‘Tennyson composes every day, but nothing will persuade him to print, or even write it down’ (Milnes, 1838, Reid, 1.220). Another Cambridge friend, G. S. Venables, urged him in August/September 1838:

Do not continue to be so careless of fame and of influence. You have abundant materials ready for a new publication, and you start as a well-known man with the certainty that you can not be overlooked, and that by many you will be appreciated. If you do not publish now when will you publish? (Letters, 1.163–4)

On 25 November 1839 FitzGerald all but gave up:

I want A. T. to publish another volume: as all his friends do: especially Moxon, who has been calling on him for the last two years for a new edition of his old volume: but he is too lazy and wayward to put his hand to the business. (Letters of Edward FitzGerald, 1.239)

Then there was the American threat. To the importunate FitzGerald Tennyson wrote c.22 February 1841: ‘You bore me about my book: so does a letter just received from America, threatening, though in the civilest terms that if I will not publish in England they will do it for me in that

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Great Yarmouth, 1824 - 1897, London

Kelloe, England, 1806 - 1861, Florence

Bredfield, England, 1809 - 1883, Merton, England

London, 1809 - 1885, Vichy

Kolkata, India, 1811 - 1863, London

London, 1830 - 1894, London

Coventry, England, 1847 - 1928, Tenterden, England

Headingley, England, 1835 - 1913, Ashford, England