Ellen Terry

Coventry, England, 1847 - 1928, Tenterden, England

Early acting career

Trained by her parents, Ellen went on the stage as a child, her first part being the boy Mamillius in Charles Kean's production of The Winter's Tale, on 28 April 1856, at the Princess's Theatre in London. Under Kean's management of the Princess's, which ended in 1859, she also played Puck in A Midsummer Night's Dream (1856), Arthur in King John (1858), and Fleance in Macbeth (1859). Her salary was initially 15s. a week, rising to 30s. during A Midsummer Night's Dream. Mrs Kean gave her further training, concentrating especially on the child's voice so that she could easily be heard in the gallery of the theatre. During the summer, when the Princess's was closed, her father successfully organized a drawing-room entertainment of two short plays, which she acted at the Royal Colosseum, Regent's Park, London, and then on tour.

By 1859 Ellen Terry was already an experienced juvenile actress with a reputation for fresh, high-spirited comedy. In that year she played in Tom Taylor's comedy Nine Points of the Law at the Olympic Theatre, and then in 1861 joined the company of the Royalty Theatre in Soho, which included W. H. Kendal, David James, and Charles Wyndham. While in London she lived with her family at 92 Stanhope Street, near Regent's Park. In 1862 she became a member of J. H. Chute's well-known stock company at the Theatre Royal, Bristol, which also performed at the Theatre Royal, Bath. Here she stayed until 1863, when she went to London again to play in J. B. Buckstone's company at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket, in a repertory that included Shakespeare, Sheridan, and modern comedy.

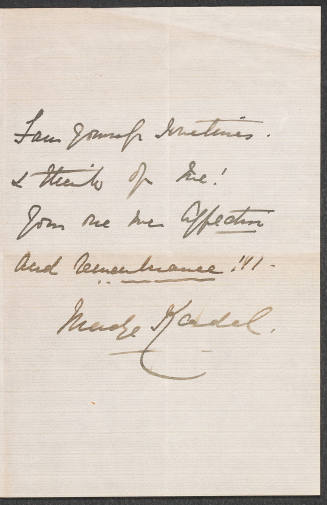

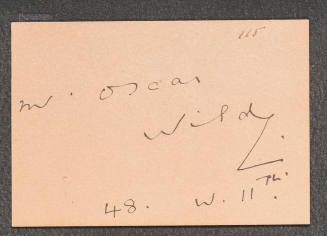

Marriage to G. F. Watts

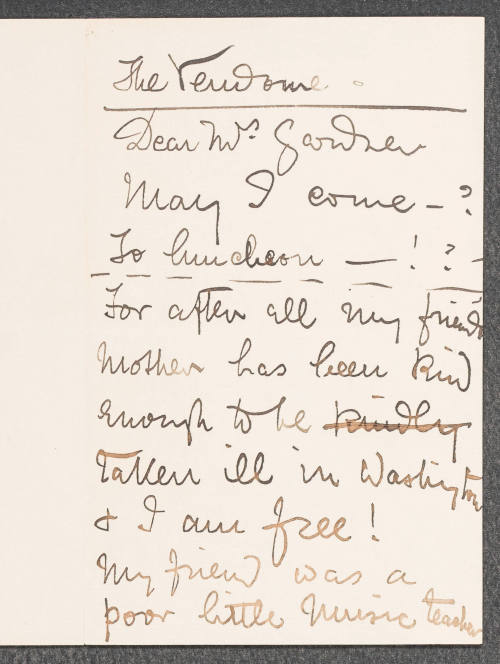

During the run of Taylor's hit comedy Our American Cousin at the Haymarket, in which she played Mary Meredith, Ellen Terry abruptly left the stage to prepare for her marriage with the celebrated artist George Frederic Watts (1817–1904). They were married on 20 February 1864 at St Barnabas, Kensington, and went to live in Little Holland House, Kensington, the residence of Mrs Thoby Prinsep. Watts was forty-seven, and Ellen Terry a week short of her seventeenth birthday. The disparity between their ages and temperaments was marked, and the young Mrs Watts was regarded with suspicion and perhaps hostility by the circle of married ladies, including Mrs Prinsep, who had appointed themselves protectresses of their adored ‘Signor’ as they termed him. The marriage lasted less than a year, and in 1865 the shocked young wife, who did not wish the separation forced upon her, found herself back with her family. In some respects the marriage was an artistic success if a personal failure. Ellen Terry added to her acquaintance a number of cultured and important people, among them Browning, Tennyson, Gladstone, Disraeli, and the photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, and was widely exposed to the arts. She and her husband entered into a productive if short-lived artistic relationship. He had painted her in 1862 in The Sisters, when she sat for him with Kate; she now happily modelled for the paintings Watchman, what of the Night, Choosing, Ellen Terry, and Ophelia. For many years after the marriage she was a cult figure for poets and painters of the later Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic movements, including Oscar Wilde. Tall, slender, with beautiful flaxen hair, grey eyes, full red lips, finely framed features, graceful of carriage and movement, fresh and always young, Ellen Terry was as much an art object as an actress.

Resumption of acting, relationship with E. W. Godwin, and birth of children

Compelled to return to the stage, in which she now took little pleasure, to earn her living, Ellen Terry in 1867 joined the company at the Queen's Theatre, Long Acre, under the management of Alfred Wigan. Here she acted for the first time with Henry Irving, in Garrick's adaptation of The Taming of the Shrew, Kathrine and Petruchio, she playing the former and he the latter; both, she said, performed badly. In the summer of 1868 she left the stage once more, to live with the architect, interior designer, and essayist Edward William Godwin (1833–1886), in the Hertfordshire countryside on Gusterwood Common. She had met Godwin while acting in Bristol, and resumed the acquaintance in London. Godwin had been widowed in 1865. His knowledge of colours and fabrics, his interest in oriental design, and his preference for simplicity of style permanently influenced Ellen Terry's taste and her choice of design schemes for her own residences and of materials for her own clothing and stage costumes. After her return to the stage and their separation Godwin continued to design costumes for her. She, however, was to remain away from the theatre for six years; during this time she bore Godwin two children: Edith Ailsa Geraldine Craig, born on 9 December 1869, and (Edward Henry) Gordon Craig, born on 16 January 1872. After her daughter's birth, Godwin designed and built a house for his new family at Fallows Green, Harpenden, Hertfordshire, and Ellen Terry lived there until 1874. Godwin became preoccupied with problems arising from his architectural practice and was often away from home; he also suffered increasing financial difficulties. Concerned for the future security of her small children, Ellen Terry left Hertfordshire in 1874 and went back to work in the theatre. A chance encounter in the Hertfordshire countryside with her old friend the playwright Charles Reade had led to an engagement at the Queen's Theatre in Reade's drama The Wandering Heir, at a handsome salary of £40 a week; she replaced Mrs John Wood in the leading part on 27 February 1874.

Ellen Terry toured in a trio of Reade plays and then distinguished herself as Portia in the Bancrofts' production of The Merchant of Venice at the Prince of Wales's Theatre in 1875. The separation from Godwin occurred in this year, while she was living in a house on Taviton Street, off Gordon Square. After several more roles at the Prince of Wales's, including Blanche Haye in a revival of T. W. Robertson's Ours in 1876, she joined John Hare's company at the Court Theatre. When she was with Hare, she moved with her children from lodgings in Camden Town to Rose Cottage at Hampton Court. Her greatest success with Hare was as Olivia in W. G. Wills's eponymous adaptation of The Vicar of Wakefield; it was a role that she also played at Henry Irving's Lyceum. On 21 November 1877, having received a divorce from Watts, she married the actor (formerly soldier) Charles Clavering Wardell (1839–1885) at St Philip's, Kensington. Wardell, whose stage name was Kelly, was thirty-eight, and the two had met while acting together in Reade's plays in 1874. They went to live, with the children, at 33 Longridge Road, Earls Court. The marriage lasted less than three years—they were separated in 1881—but it was at least the cause of a reconciliation with her mother and father, whom she had not seen since her alliance with Godwin.

Professional and personal relationship with Henry Irving

In July 1878, Henry Irving (1838–1905), who had entered into a lease for the Lyceum Theatre, called on Terry at Longridge Road; they had not met since 1867. The outcome was a contract at the Lyceum at a salary of 40 guineas a week and an annual benefit performance; her touring salary, for much of her Lyceum career, was a generous £200 a week. Her first part at the Lyceum was Ophelia, on 30 December 1878, the day Irving inaugurated his new management with Hamlet. Irving was employing a leading lady, an experienced actress of thirty-one, who already possessed a considerable reputation, a devoted audience following, and a memorable recent appearance as Portia. Ellen Terry was to remain with Irving for twenty-four years, undertake frequent provincial tours and seven tours to America with the Lyceum company, and play a total of thirty-six parts. Eleven of these were in Shakespeare; she also acted in plays by Tennyson, Bulwer-Lytton, Reade, Sardou, and other contemporary playwrights, such as W. G. Wills, who were commissioned by Irving to write for the Lyceum. Irving's repertory consisted mostly of Shakespeare and Victorian romantic melodrama, with the occasional comedy, and of course Terry did not have, since Irving was an absolute if benevolent dictator, a free choice of parts.

Certainly Terry achieved her greatest distinction in Shakespeare, especially in Shakespearian comedy. Her Shakespearian parts at the Lyceum were Ophelia, Portia (The Merchant of Venice, 1879), Desdemona (Othello, 1881), Juliet (Romeo and Juliet, 1882), Beatrice (Much Ado about Nothing, 1882), Viola (Twelfth Night, 1884), Lady Macbeth (Macbeth, 1888), Queen Katherine (Henry VIII, 1892), Cordelia (King Lear, 1892), Imogen (Cymbeline, 1896), and Volumnia (Coriolanus, 1901). She also played Lady Anne in a scene of Richard III for Irving's benefit performance in 1879. Her last appearance at the Lyceum was as Portia on 19 July 1902, but she did tour the provinces with Irving and the Lyceum company in the autumn of that year. Of her principal non-Shakespearian roles at the Lyceum, her most successful and critically esteemed were Queen Henrietta Maria in Wills's drama Charles I (1879), Camma in Tennyson's short tragedy The Cup (1881), Margaret in the immensely popular and long-running Wills version of Faust (1885), Nance Oldfield in Reade's romantic comedy of the same name (1883), and Olivia (Olivia, 1885).

Ellen Terry's close association with Irving over such a long period of time may also have involved a sexual relationship. Some contemporaries and later biographers declared that they were lovers. Irving was separated, but not divorced from his wife. Terry was separated from Wardell in 1881; he died in 1885. Irving was godfather to both her children. They were close to one another, not only professionally at the Lyceum, but also in private life. They went on holidays together, and Irving wrote her letters that can only be described as tender, loving, and committed. Yet there is no decisive evidence of a physical love affair, only a possibility which some see as a probability, some as a certainty. Terry had a great admiration for Irving as an actor and as a hard worker, although she could clearly perceive his faults.

The stage after Irving

Terry's lengthy and famous correspondence with George Bernard Shaw, which was especially prolific between 1895 and 1900, and much of which consisted of his advice on her acting and his attempts to woo her away from the Lyceum, represented an affectionate relationship of another kind, for they met only occasionally until the rehearsals for Captain Brassbound's Conversion in 1906. Her replies reveal a great deal about both her art and her personality.

During the Lyceum years Ellen Terry changed residence more than once. In 1889 she moved to 22 Barkston Gardens, Earls Court, but, still remaining fond of the country and remembering the house at Harpenden, she lived from time to time, when she was not required in London or on tours, in a series of rural dwellings. One of them was a small public house at Uxbridge, the Audrey Arms, in which she was required by the terms of her lease to act as publican. Evidently she kept the beer so poorly that she had virtually no customers. In 1896 she occupied Tower Cottage by the town gate in Winchelsea, Sussex, and in 1900 acquired her last country home, Smallhythe, a fifteenth-century farmhouse just south of Tenterden, Kent. It is now owned by the National Trust and functions as an Ellen Terry museum, library, and archive. She moved her London residence in 1902 from Barkston Gardens to 215 King's Road, Chelsea.

In 1889 Terry's son Teddy joined the Lyceum company as an actor in a drama of the French Revolution, Watts Phillips's The Dead Heart; he had earlier walked on when the company was on tour in Chicago. He remained with the Lyceum, and acted in the provinces, until 1897, when he left the stage to study drawing and produce his first woodblock engravings. His sister, Edy, who also appeared at the Lyceum for several years from 1887 in small parts, became much more interested in costume design than acting. She designed costumes for her mother and for productions staged by Lillie Langtry and Mrs Brown Potter in the early years of the twentieth century.

After she finally left the Lyceum, Ellen Terry did not lack invitations to act, although her age now restricted the kind of parts she could play. Her best post-Lyceum role was her first, Mistress Page in The Merry Wives of Windsor, under the management of Herbert Beerbohm Tree, at His Majesty's on 10 June 1902. Her performance was a triumph, and with Tree playing Falstaff and Madge Kendal as Mistress Ford the play ran for 156 performances. In 1903 Terry made a financially unfortunate move into management when she took the Imperial Theatre for a season, chiefly to introduce the designing and directing talents of her son to an as yet unknowing and uncaring professional world. Ibsen's The Vikings at Helgeland opened in April 1903, with set and lighting design and properties as well as direction by Craig, and the costumes, designed for a large cast, by his sister. Their mother acted the role of the fierce and warlike Hiordis, in which she was miscast. There were tensions between actors and director and between director and business manager, and the public did not come. The Vikings was withdrawn after only thirty performances, and the big losses were only partially recompensed by a cheaply and hastily mounted Much Ado about Nothing which then toured successfully in the provinces. It was the only occasion when this formidably talented family collaborated on an event of major theatrical significance. After this Craig left England for Europe, his own career as a designer and theorist, and Isadora Duncan. Edy founded the feminist-oriented Pioneer Players in 1911, directed plays for them, and looked after her mother. The relationship between mother and daughter was not an easy one.

Ellen Terry remained active in the theatre for a few more years, despite increasing health problems. She created the part of Alice in J. M. Barrie's Alice Sit-by-the-Fire at the Duke of York's Theatre in 1905, and, finally submitting to Shaw's constant hounding, took a part in one of his plays: Lady Cecily Waynflete in Captain Brassbound's Conversion at the Royal Court in 1906. Soon after this, on 12 June 1906, an Ellen Terry jubilee performance, marking her fifty years on the stage, was organized at Drury Lane by the theatrical profession. It raised for the actress a much needed £6000. Enrico Caruso, Paoli Tosti, Nellie Melba, and a host of leading actors, actresses, and entertainers went through a substantial and varied programme. Like a grand and beautiful divinity, Terry herself finally appeared on the stage in an act of Much Ado about Nothing (performed by no fewer than twenty-two members of the Terry family) to the worshipful plaudits of a packed house. Later in 1906 she played Hermione in Tree's production of The Winter's Tale at His Majesty's. She toured America in 1907 with Captain Brassbound's Conversion, and took the role of Aunt Imogen in W. Graham Robertson's fairy play Pinkie and the Fairies at His Majesty's in 1908. She still did provincial tours, including one of the Shaw play, and in 1910–11 visited America once more with a programme of lectures on and recitations from Shakespeare. On this tour she visited a recording studio and recorded five passages from Shakespeare, the only extant evidence of the sound of her voice. She later gave her Shakespeare programme in Britain and visited New Zealand and Australia with it in 1914–15. There followed scenes from Shakespeare performed in music-halls under the management of Oswald Stoll, and her last Shakespearian part was the Nurse in Romeo and Juliet (1919) at the Lyric, Shaftesbury Avenue. She also appeared in at least five films, and her last stage role was Susan Wildersham in Walter de la Mare's fairy play Crossings, on 19 November 1925 at the Lyric, Hammersmith. She had been on the stage for sixty-nine years.

Marriage to James Carew, honours, and death

On 22 March 1907 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Ellen Terry married her third husband, the American actor James Carew (1876–1938), whom she met at the Royal Court and with whom she toured America in Captain Brassbound's Conversion. Carew was thirty-one. The marriage broke up amicably in 1910. The Chelsea house was given up in 1921; for some years Terry's financial condition had been poor and her financial affairs disorganized, and she moved, in worsening health, to a flat in Burleigh Mansions, St Martin's Lane. St Andrews University conferred an honorary LLD upon her in 1922, and in the new year's honours list of 1925 she was made a dame grand cross of the British empire, only the second actress to be so honoured. In 1927 she suffered an attack of bronchial pneumonia. On 21 July 1928 she died at Smallhythe of a cerebral haemorrhage. After a ceremony at Smallhythe church on 24 July, her body was taken to the crematorium at Golders Green, Middlesex, and another ceremony took place that evening at St Paul's, Covent Garden. Her ashes were interred in St Paul's in August 1929, and a memorial tablet was unveiled by Sir John Martin-Harvey.

A great actress

Aside from the great appeal of her Aesthetic and Pre-Raphaelite image, Ellen Terry found her way into the hearts of her public by her liveliness, irrepressible spirits, and sense of fun in high comedy; her warmth, sincerity, trustfulness, and depth of romantic feeling in love scenes; her transparent innocence and beauty of mind in most characterizations; and her power to arouse the deepest pathos. She was a beautiful woman, and until late in her career never seemed to grow old; a sense of happy, everlasting youth invested her on stage. It is not surprising that her greatest part was Beatrice, and all the critics agreed that she would have made a superb Rosalind. She never played the part because Irving, although he did put on plays for her sake, such as Olivia, which offered little for him and a great deal for her, did not think fit to produce As You Like It and demean himself in, probably, the small part of Jaques. By the time she left the Lyceum she was too old for Rosalind. Terry's Margaret in Faust combined her ability to portray tenderness, innocence, and love as well as to arouse sorrow because of her suffering; this combination also made her Desdemona and Imogen effective. She was not, despite her best efforts, capable of tragedy. She admitted herself that she lacked stamina for long speeches; she also lacked physical force and the ability to sustain strong emotion. Her very personality was not suited to tragedy. In her hands Lady Macbeth was a fragile, devoted wife easily crushed by the weight of her husband's ambition and estrangement from her. The sleep-walking scene was played for pathos rather than tragic power. Volumnia was a ‘true woman’, as one critic put it, busying herself with the domestic tasks of a Victorian household.

From the point of view of acting technique, Ellen Terry was noted for grace, charm, and lightness; words such as ‘gliding’, ‘floating’, and ‘dancing’ were used to describe her stage movement, in which she tended to restlessness. Her voice was distinct, melodious, and musically pitched, with a noticeable vibrato in moments of deep emotion. Early in her career she was afflicted with stage fright on first nights; later she had difficulty remembering lines, a problem that grew much worse toward the end and severely hampered her in the playing of new parts. She worked extremely hard in preparing a role, sometimes filling several copies of a play with extensive marginalia and underlinings, giving herself specific instructions on textual emphasis, pace, pitch, volume, and movement, as well as comments on character. She always appeared natural on the stage; sometimes it seemed as if she were not acting at all, but merely being Ellen Terry. Indeed, her method was to absorb parts into herself, to possess a character rather than change herself into one.

None of her faults seemed to matter. In a real sense she was beyond serious criticism, the acerbic Henry James being the only critic who steadily gave her bad reviews, and even he occasionally dwindled into praise, notably when reviewing her Imogen. She was one of the very few English actresses to be adored by her public. They respected and admired Irving, a great artist but not a lovable man; they doted on Terry. She was not a tragic actress, and like Irving disliked the new drama represented by Ibsen and his followers. She did not, like Eleanora Duse, whom she much admired, venture into new dramatic territory. Her acting range may have been limited, but within it she was incomparable.

Michael R. Booth

Sources

Ellen Terry's memoirs, ed. E. Craig and C. St John (New York, 1932) [with notes and biographical chapters by eds.] · E. Terry, The story of my life (1908) · Ellen Terry and Bernard Shaw: a correspondence, ed. C. St John (1931) · R. Manvell, Ellen Terry (1968) · J. Parker, ed., The green room book, or, Who's who on the stage (1909) · W. G. Robertson, Time was: the reminiscences of W. Graham Robertson (1931) · B. Stoker, Personal reminiscences of Henry Irving, 2 vols. (1906) · E. G. Craig, Ellen Terry and her secret self (1932) · C. St John, Ellen Terry (1907) · C. Hiatt, Ellen Terry and her impersonations (1908) · L. Irving, Henry Irving: the actor and his world [1951] · J. Martin-Harvey, The autobiography of Sir John Martin-Harvey (1933) · b. cert. · m. cert. [G. F. Watts] · m. cert. [C. C. Wardell] · d. cert. · J. Parker, ed., Who’s who in the theatre, 11th edn (1952)

Archives

BL, letters, Add. MS 46473 · Ellen Terry Memorial Museum, Smallhythe, Kent, corresp. · Hunt. L., letters · Russell-Cotes Art Gallery and Museum, Bournemouth, papers · University of Washington, corresp. and papers :: BL, corresp. with George Bernard Shaw, Add. MSS 43800–43802, 46172g · Bodl. Oxf., letters to various members of the Lewis family · LMA, letters to Ida Donisthorpe [copies] · NYPL, corresp. with Edward Craig · V&A, theatre collections, letters to lord chamberlain's licensee and others; letters to Peter McBride FILM

BFINA, current affairs footage SOUND

BL NSA, performance recordings

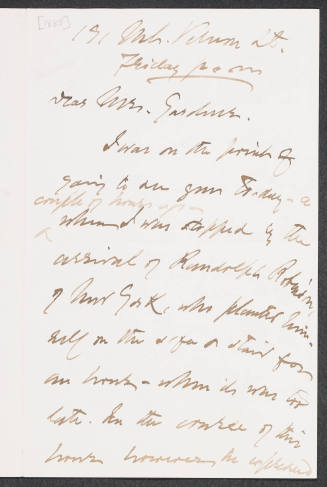

Likenesses

M. Laroche, double portrait, salt print, 1856 (with Charles Kean as Leontes and Mamillius), NPG · G. F. Watts, oils, 1862 (with her sister), Eastnor Castle, Herefordshire · J. M. Cameron, photograph, 1864 · London Stereoscopic Company, group portrait, albumen print, 1864 (The Green Room), NPG · G. F. Watts, oils, c.1864 (Choosing), NPG · G. F. Watts, oils, 1864, Watts Gallery, Compton, Surrey · G. F. Watts, oils, c.1864–1865, NPG; repro. in G. F. Watts, Watchman, what of the night · J. Forbes-Robertson, oils, 1876, NPG · W. Brodie, marble bust, 1879, Royal Shakespeare Memorial Theatre Museum, Stratford upon Avon · Bassano, half-plate glass negative, 1880, NPG · A. L. Merritt, etching, 1880, NPG · A. L. Merritt, oils, 1883, Garr. Club · Elliott & Fry, chlorobromide print, 1884, NPG · Elliott & Fry, two half-plate negatives, 1884, NPG · H. R. Barraud, carbon print, 1888, NPG; repro. in Men and Women of the Day (1888) [see illus.] · J. S. Sargent, oils, 1888–9, Tate Collection · Walery, carbon print, 1889, NPG · G. G. Manton, group portrait, watercolour drawing, 1891 (The Royal Academy conversazione, 1891), NPG · J. Collier, group portrait, oils, 1904, Garr. Club · J. F. Pryde, oils, 1906 (as Nance Oldfield), NPG · J. S. Sargent, oils, 1906, NPG · C. J. Becker, pencil drawing, 1913, Royal Shakespeare Memorial Theatre Museum, Stratford upon Avon · W. G. Robertson, oils, 1922, NPG · C. Roberts, chalk drawing, 1923, NPG · A. Broom, group portrait, photograph, NPG · J. M. Cameron, photograph, U. Texas, Gernsheim Collection · E. G. Craig, pen, ink, and wash drawing (as Mrs Page in The Merry Wives of Windsor), V&A · E. M. Hale, oils, Russell-Cotes Art Gallery, Bournemouth · HM, caricature, pen-and-ink drawing (with Irving), V&A, theatre collections · P. M., pen-and-ink drawing, NPG · B. Partridge, three portraits, black and white gouache, NPG · W. G. Robertson, oils (after his pastel drawing), Ellen Terry Memorial Museum, Smallhythe Place, Kent · Window & Grove, cabinet photographs, NPG · oils (as Portia), Garr. Club · pencil drawing, Garr. Club · photographs, V&A, theatre collections · plaster cast of death mask, NPG · prints, BM, NPG, Harvard TC

Wealth at death

£22,231 1s. 2d.: probate, 12 Oct 1928, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–16

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Michael R. Booth, ‘Terry, Dame Ellen Alice (1847–1928)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/36460, accessed 24 Oct 2017]

Dame Ellen Alice Terry (1847–1928): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36460

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Keinton Mandeville, England, 1838 - 1905, Bradford, England

Lincolnshire, England, 1848 - 1935, Hertfordshire, England

Brighton, 1872 - 1898, Menton, France

London, 1843 - 1932, Godalming, England