Sarah Bernhardt

Paris, 1844 - 1923, Paris

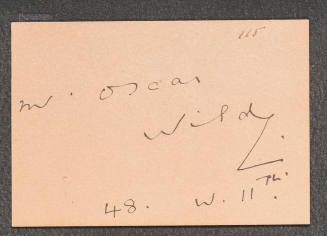

Sarah Bernhardt was not simply the most famous actress the world has seen; she was among the most gifted. Her talents were first established at the Comédie Française; later they were displayed in a carefully selected repertory of tested favourites whose range she augmented with controlled experiment. Working within the Romantic tradition, she created exciting entertainment out of wild emotion, yet never quite lost her ability to touch the heights and depths of tragic understanding. There had been other stars before her, but the scale of Bernhardt's success resulted from her ability to harness the resources of the modern world. She first realized this potential in London, and throughout her life regularly returned to the capital, where she mixed with an artistic élite that included Ellen Terry and Oscar Wilde, influencing countless British actresses whose theatrical tastes, for Ibsen and for ‘problem plays’, were often very different from her own. It was Bernhardt's ability to dominate the stage intellectually without forsaking physical elegance that set the technical challenge; recent scholars have shown, too, that in London, from start to finish, she held particular sway over the female members of her audience, for whom she offered a startling example of how to live an independent yet glamorous life.

For a female performer to maintain direction over her career required vision and tenacity. Bernhardt turned those qualities to further account by incorporating them within her performances, and by allowing them to become part of her legend. An overall impression of self-determination, even in the most fragile of roles, accounts, in large part, for her enduring appeal.

Early career

Bernhardt's life could easily have turned out differently: she was born into the demi-monde, the Parisian milieu of high-class prostitutes, wayward aristocrats, and bohemian artists. Her mother had two sisters: Rosine Berendt, another courtesan, who died of tuberculosis in 1873, and the more responsible Henriette, who played some part in bringing up Sarah and her siblings, Régine and Jeanne. Sarah, though, was educated away from home, at the Institution Fressard in Auteuil and at Grandchamp, an Augustine convent near Versailles. The move, by no means decisive, from demi-monde to theatre came in 1860, when she entered the Paris Conservatoire, where she was instructed by three magisterial figures—François Joseph Pierre Regnier, Jean-Baptiste François Provost, and Joseph Isidore Samson. Despite a disappointing second prize in the final competition she went on to the Comédie Française, and made an unremarkable début in the title role of Racine's Iphigénie in August 1862. After two more roles and a ferocious quarrel with an elderly sociétaire she moved to the Théâtre du Gymnase, where she tried out her skills in more popular genres. Yet her performances were still not particularly well received and her career prospects remained far from certain, a professional situation made all the more precarious by the birth of her son, Maurice, on 22 December 1864. The father, or so she later let it be known, was a Belgian aristocrat, Prince Charles Lamoral de Ligne, though Bernhardt brought the child up single-handedly.

France conquered

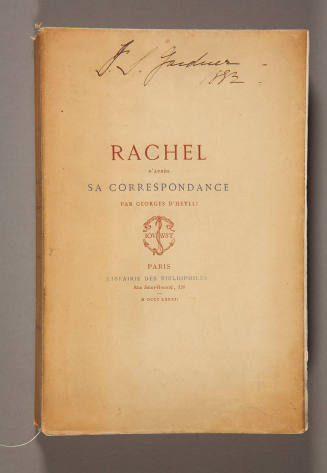

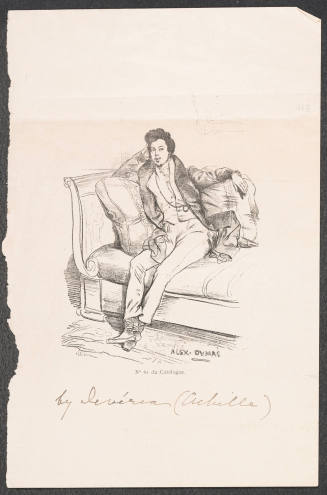

In 1866 Bernhardt joined the Théâtre de l'Odéon, France's second national theatre; here she established an artistic rapport with the director, Félix Duquesnel. She made her official Odéon début as Armande in Molière's Les femmes savantes in 1867, and followed that with Anna Danby in Kean by Dumas père, and the travesti role of the troubadour, Zanetto, in Le passant by François Coppée. In February 1872 she scored massively as Doña Maria in Victor Hugo's Ruy Blas. Now established, she returned to the Comédie Française, where Emile Perrin had become director. A series of increasingly significant roles followed: Gabrielle in Dumas père's Mademoiselle de Belle-Isle in November 1872, Junie in Racine's Britannicus in December, the title role in Andromaque in August 1873, and the lead in L'étrangère by Dumas fils in February 1876. In 1877 she again triumphed in Hugo, as a captivating Doña Sol in Hernani. She had played the minor role of Aricie in Racine's Phèdre in September 1873; in December 1874 she returned to the play, this time as its heroine. Superimposing herself on memories of Rachel Félix, whose Phèdre had been a pillar of self-recrimination, she portrayed a more forgiving woman whose languor invited audiences to sympathize with, even to desire, her erotic condition. Of all the parts Bernhardt played in her career, Phèdre, victim of her own passions, was the most absorbing, for actress and audiences alike.

International triumph

In 1879 the Comédie Française appeared in London for a season. Advance publicity had already established Bernhardt as the company's most charismatic member, a reputation that she consolidated in ways that, though lucrative to her personally, were not always acceptable to the company's administrators: she exhibited her own sculptures, gave private recitals, and became a favourite in high society.

The London reception made it clear that here was too volatile, and too valuable, a talent to be contained within hierarchical confines, and Bernhardt took the irrevocable decision to move into the commercial market. In the spring of 1880 she tried out her repertory with seasons in London and Brussels before departing in October 1880 for America, where she opened in New York with Adrienne Lecouvreur by Eugène Scribe.

The first few years of Bernhardt's artistic independence were insecure, and her success became guaranteed only as she developed the idea of reviving proven vehicles associated with actresses from earlier periods. These she reinvigorated with her own modern personality: Adrienne Lecouvreur written for Rachel, Frou-Frou, by Meilhac and Halévy, in which Aimée Desclée had made her name, and the part for which Bernhardt is, even now, most remembered, Marguerite Gautier in Dumas fils's La dame aux camélias, a role that was already nearly thirty years old when she first introduced it in 1881.

Many of Bernhardt's roles have it in common that an apparent emotional weakness turns out to be the precondition for some heroic act of self-sacrifice. By performing these parts with extravagant passion she converted a maudlin, even misogynistic, tradition into a theatrical experience that modern audiences could view with awestruck enjoyment. But the actress paid a price for her insistence that emotional intensity was the defining quality of femininity. Introversion, sub-textual motivation, the deeper psychological qualities that were being explored by contemporary dramatists, would never be fully available to her. This became overwhelmingly true once she had added a final ingredient to the theatre of sensuality—exotic spectacle. Her co-conspirator was the playwright Victorien Sardou. Together they devised a theatrical formula requiring exotic locations and dazzling costumes that served them well in a series of lavish melodramas: Fédora (1882), Théodora (1884), La Tosca (1887), Cléopâtre (1894), Gismonda (1897), Spiritisme (1897).

The first American tour had also seen the début of ‘Sarah Barnum’, a satirical nickname for the actress as a vibrant entrepreneuse whose manipulation of the publicity machine knew no limits, but who brought such wit and gaiety to the business of self-promotion that press and public were, for the most part, happily complicit. This provided the foundation for many later visits to America between 1886 and 1916. Bernhardt's appetite for travel was boundless. She went to Russia in 1881 and South America in 1886, and embarked on a world tour in 1891 which lasted until 1893. Bernhardt's London seasons became an established routine, and she visited annually throughout the 1890s—although this familiarity did her some damage among advanced critics, who became increasingly disrespectful. Bernard Shaw was the most notorious hammer of her reputation, but others such as William Archer could be equally unforgiving about her reliance on old-fashioned techniques.

Private life and management

Bernhardt lived much of her private life in public. As the press, increasingly internationalized and intrusive, turned her life into myth, so audiences found it hard to resist making connections between her roles and her lifestyle. In April 1882 she married Aristidis Damala (1857–1889), a Greek diplomat, and tried unsuccessfully to launch him on an acting career; he died a miserable death from drug addiction in 1889. She also had semi-public relationships with a number of her leading men, including the actors Jean Mounet-Sully, Jeanne Richepin, and, a late liaison, Lou Tellegen (b. 1883). These only added to her aura. Surrounded by unusual pets (a cheetah, monkeys), a lifetime's collection of bizarre objects, and an entourage of devoted admirers, she presented a formidable face to the world. Bernhardt's consumption of its luxuries was conspicuous; and yet she was said to be sometimes possessed by fits of ungovernable rage, encouraging the contemporary diagnosis of neurasthenia. She seemed, as she no doubt intended, to be the archetype of fin de siècle womanhood.

Bernhardt did have her commercial and artistic failures: Lady Macbeth in 1884, a production of Hamlet in which she played Ophelia in 1886. These became more serious once she had entered into theatre management herself. Her most distinguished period as a manager lasted from 1893 to 1899, when she ran the Théâtre de la Renaissance; her subsequent tenancy of the vast Théâtre des Nations (renamed the Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt) was less consistently distinguished. Throughout the 1890s, though, she countered the inroads made by the new drama of Ibsen and the symbolists with an innovative range of plays: Jeanne d'Arc by Barbier, Amphytrion by Molière, Magda by Suderman, La princesse lointaine by Rostand, Lorenzaccio by de Musset. At an 1896 banquet in her honour she could boast that she had played ‘one hundred and twelve roles, and created thirty-eight new characters, sixteen the work of poets’. In 1897 she introduced Rostand's La samaritaine and, in the same year, in a publicly orchestrated contest of divas, survived comparison with a younger rival when the far more naturalistic Eleonora Duse appeared in Paris.

Later career

By 1900 Bernhardt was a cornerstone of France's national life as well as a citizen of the world. She had always been a notable patriot—opening up the Odéon as a convalescent hospital during the Franco-Prussian War, consorting with both sides during the commune, intervening in the Dreyfus affair. Patriotism infused her repertory too when, in March 1900, she took on the role of L'Aiglon, Napoleon's son, in a play by Rostand. Travesti was nothing new to her: early on she had endeared herself to audiences in Le passant; in May 1899 she performed Hamlet, to mixed reactions. In 1905 she experimented with playing the male lead to Mrs Patrick Campbell's princess in Maeterlinck's Pelléas et Mélisande.

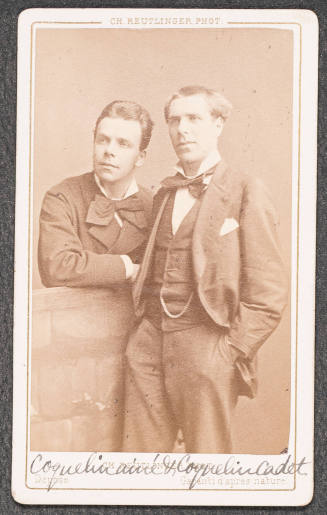

Nevertheless the new century was demanding, not least because of a leg injury that led to amputation in 1915. In 1910 and 1911 Bernhardt appeared at the Coliseum music hall in London, where she performed extracts from La Tosca and L'Aiglon between animal acts and acrobatic turns and, remarkably, held her own. What looks like a severe decline in professional status can also be seen as part of her determination to keep abreast of modern developments: she made silent films and sound recordings, toured with Constant Coquelin, and was hailed as an inspiration by American suffragettes.

In 1914 Bernhardt was created a chevalier of the Légion d'honneur, and the outbreak of hostilities again found her eager to make her contribution. She introduced a patriotic entertainment, Les cathédrales, by Eugène Morand, and campaigned for the war effort in the United States. In later life she took time to write a novelistic autobiography, Ma double vie (1907), which was eventually followed by an autobiographical novel, Petite idole (1920), and an acting primer, L'art du théâtre (1923), in which she made partial peace with the Paris Conservatoire. Her final appearances were extraordinary, especially in Racine's Athalie in 1920 and in Daniel by Louis Verneuil, a play about a morphine addict, in which she made her last appearance in London. She gave her last performance of all on 29 November 1922 in Turin. On 26 March 1923 she died in the boulevard Pénere, Paris, and, after a fittingly grandiose funeral procession, was buried in the cemetery at Père Lachaise.

It is possible to judge the career of Sarah Bernhardt by the animosity it inspired: from Chekhov in Russia, from Shaw and others in England, from embattled reformers in her native city. Today, however, it seems more than ever important to see her, as her faithful audiences did, as a premonition, a symbol of what could be achieved by a woman who engaged with the modern world on its own terms.

John Stokes

Sources

E. Pronier, Une vie au théâtre: Sarah Bernhardt (1942) · G. Taranow, Sarah Bernhardt: the art within the legend (1972) · A. Gold and R. Fizdale, The Divine Sarah (1991) · R. Brandon, Being divine: a biography of Sarah Bernhardt (1991) · E. Aston, Sarah Bernhardt: a French actress on the English stage (1989) · J. Stokes, M. R. Booth, and S. Bassnett, eds., Bernhardt, Terry, Duse: the actress in her time (1988) · R. Hahn, La grande Sarah (1930) · J. Huret, Sarah Bernhardt (1899) · M. Rostand, Sarah Bernhardt (1950) · L. Verneuil, La vie merveilleuse de Sarah Bernhardt (1942) · S. Bernhardt, Ma double vie (1907) · M. Colombier, Les mémoires de Sarah Barnum, 10th edn (1883) [this is a satire on Sarah Bernhardt]

Archives

Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, Paris · Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris, Association de la Régie Théâtrale · Bibliothèque-Musée de la Comédie Française, Paris · V&A, theatre collections

FILM

BFINA, documentary footage; performance footage · Cinémathèque Française, Paris · Museum of Modern Art, New York

SOUND

BL NSA, performance recordings; documentary recordings · NYPL, New York Library for the Performing Arts · Phonothèque Nationale, Paris

Likenesses

F. Nadar, photograph, c.1858 · J. Bastien-Lepage, portrait, 1879 · C. Beaton, pen-and-ink drawing, NPG · E. Clairon, oils (as Ruy Blas), Bibliothèque de la Comédie Française · E. Clairon, oils, Palais des Beaux Arts, Paris, France · Florian, wood-engraving (after J. van Beers), NPG · Histed, photograph, priv. coll. [see illus.] · J. Lomering, chalk drawing, NPG · portrait (after W. Nicholson), NPG · print (after photograph by F. Nadar), NPG

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

John Stokes, ‘Bernhardt, Sarah Henriette Rosine (1844–1923)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2113/view/article/57574, accessed 8 Aug 2013]

Sarah Henriette Rosine Bernhardt (1844–1923): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/57574

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated9/10/24

Boulogne, 1841 - 1909, Couilly-Pont-aux-Dames

Oakland, California, 1874 - 1965, Englewood, New Jersey

Speldhurst, England, 1864 - 1950, Zurich Switzerland

Villers-Cotterêts, France, 1802 - 1870, Dieppe, France

Calais, Maine, 1860 - 1952, Waverly, Masachusetts

Bourne, Lincolnshire, 1825 - 1895, Paris

Hamburg, Germany, 1809 - 1847, Leipzig, Germany