Henry James

New York, 1843 - 1916, London

James's early fiction was in the style of Hawthornesque romance and so continued on into the 1870s. Writing for the North American Review, he was associated with its coeditor Charles Eliot Norton, who introduced him to English literati, including John Ruskin, Charles Darwin, and Dante Gabriel Rosetti, during his year abroad alone, when he also met George Eliot. In 1875 publication of his first novel, Roderick Hudson (Watch and Ward had prior serialization, but the work was not published as a book until 1878), inaugurated his major "international" fiction in combination with major depiction of the artist as hero. That year saw publication of his first book of travel literature, Transatlantic Sketches, and his first collection of tales, A Passionate Pilgrim and Other Tales. In the title story the hero, Clement Searle, exemplifies "the latent preparedness of the American mind" to be delighted by England, a sympathy that is "fatal and sacred." This is also the theme of the novel James was working on at his death.

James's Expatriation

James began his own expatriation by moving to Paris in November 1875. He met the Gustave Flaubert group of writers (Émile Zola, Alphonse Daudet, Edmond de Goncourt, Guy de Maupassant, and Russian expatriate Ivan Turgenev), whom he called "the grandsons of Balzac." He then moved to London and entered society, something he had been unable to do when among the French, and he met William Ewart Gladstone, Herbert Spencer, Thomas Henry Huxley, and Robert Browning. He was elected to the Reform Club and to the Athenaeum. A pair of international novels, The American (1877) and The Europeans (1878), the latter reversing the usual transatlantic visit, was accompanied by his first book of critical essays, French Poets and Novelists (1878), and his first bestseller, Daisy Miller (1878). Then appeared his first critical biography, the portentous Nathaniel Hawthorne (1879): after a suitable tribute James faults his earliest mentor for being insufficiently realistic. James's novel of 1880, Washington Square, continued his new focus on heroines, which was joined to his international theme in The Portrait of a Lady (1881). Isabel Archer is a healthier-minded Daisy Miller but not less independent-minded. The innocent American in Europe is attracted to the nicely mannered Europeanized American Gilbert Osmond and marries him to share her newly won inheritance; Gilbert seems poor and deserving. Her recognition of evil at the center of her marriage is aided by the generous and loving Ralph (who got her the inheritance without her knowing its source). At his death Isabel's discovery of his generosity accompanies the realization of her maturity and courage, the achievement of a Blakean "higher innocence." She decides to refuse the various escapes open to her and to remain faithful to her discovered mature self: she returns to Rome to face Gilbert. James acknowledged (to Grace Norton) that The Portrait owed something to Minny Temple, but he did not point out that it is Ralph rather than Isabel who derives from Minny; Ralph is to Isabel as the dying Minny was to Henry James.

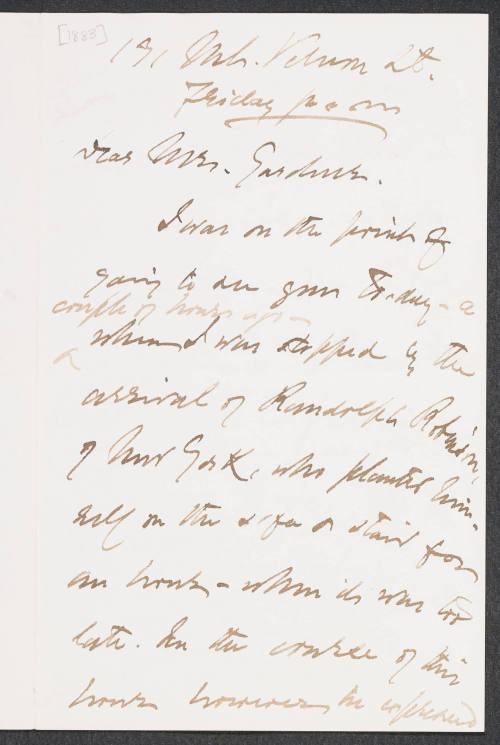

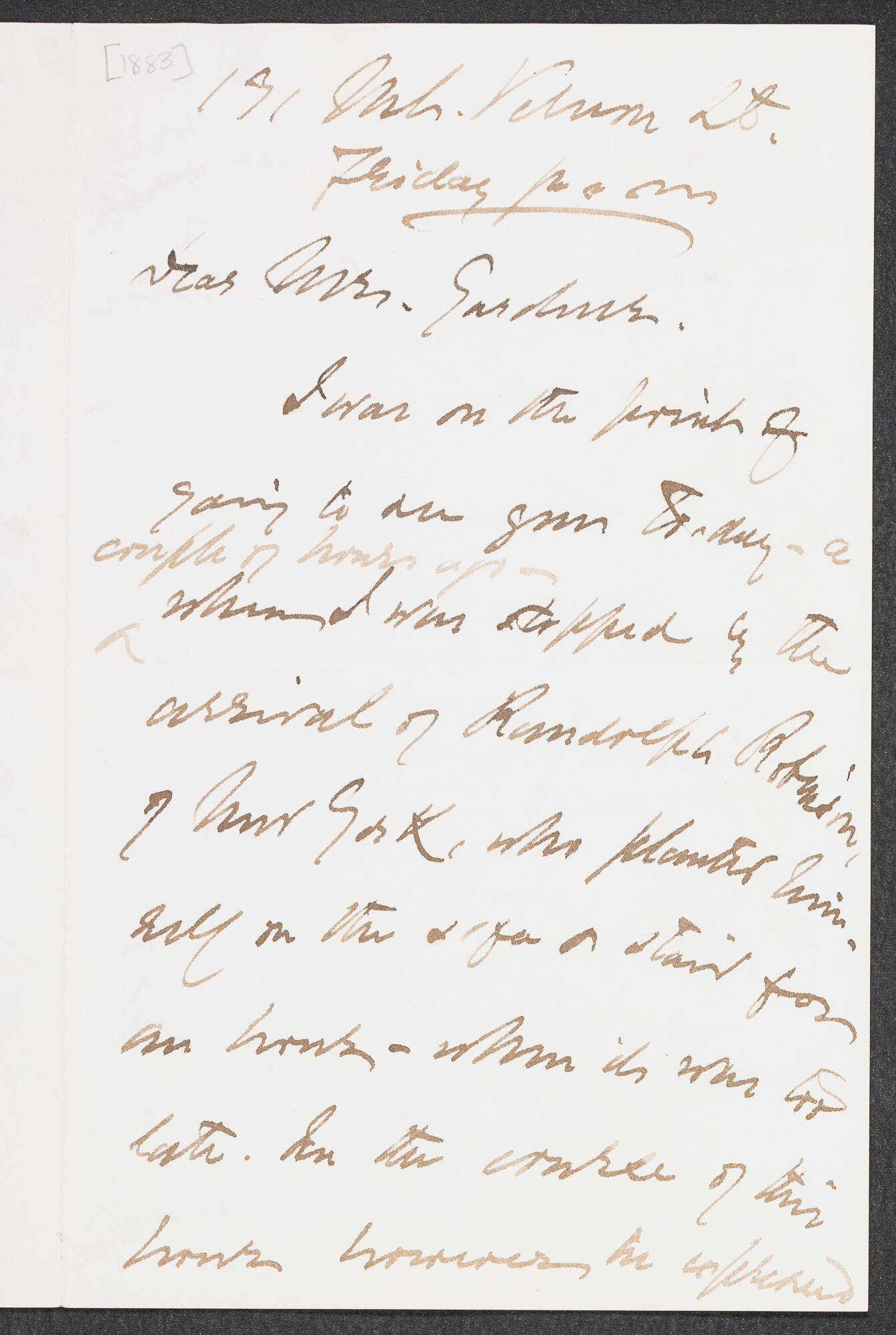

He interrupted his expatriation to return to the United States in October 1881 and was held there by the death of both parents during 1882 (although he was back in England between the two sad events). He was named executor of his father's estate and so stayed on until August 1883. He had immediately added his share of the inheritance to that of his sister, Alice (Alice James, then thirty-four), who would soon need complete care. He was particularly attentive to her (with the help of Katherine Loring) from 1884, when she came to England, until her death in 1892. Macmillan published his first Collective Edition in November 1883, by "Henry James"--no longer "Junior."

"The Art of Fiction" (1884)

In 1884 James returned to Paris. Later that year he published an essay, "The Art of Fiction," stressing the importance of "solidity of specification" in rendering "the look of things, the look that conveys their meaning." In those last six words lies the important qualification. He praises treatment of "psychological reasons," and he distinguishes between what is moral and what is mere moralizing. Finally the essay demands meaningful artistic structure, expressive form. James had recognized by this time that the phenomenon of American tourists in Europe provided him with the metaphor of his international theme. For his fictions are not merely studies in cultural contrasts (the look of things) but, via that surface presentation, comments on the human condition (the meaning that their look conveys). His three novels of the later 1880s, The Bostonians (1886), The Princess Casamassima (1886), and The Tragic Muse (1890), exemplify the precepts of "The Art of Fiction" and intentionally follow the lead of his French contemporaries; they are his own version of Zola's "experimental novel," realistic (or naturalistic) portrayal of the influence of heredity and environment. The basic distinction between James and his French confrères is his psychological emphasis, the focus on what his characters believe about their hereditary makeup rather than the makeup itself. The characters' "point of view" is really the determining factor.

In December 1888 actor-manager Edward Compton invited James to turn The American into a play for his company and thus opened a new phase in James's career. James had published four plays but none had been produced. He knew the theater, especially the French theater, very well, and the dramatic mode appealed to him because of its immediate contact with its audience. He accepted Compton's offer and wrote to his friend Robert Louis Stevenson that The Tragic Muse would be his last long novel. He would write plays and "short lengths." The Tragic Muse dealt with the sacrifices demanded by art. Actress Miriam Rooth gives up an advantageous marriage to an English diplomat in order to pursue her art, and Nick Dormer disappoints the political ambitions of his family and potential (and wealthy) bride in order to pursue a career as a painter. The novel embodied art in conflict with the world.

Protracted visits to the Continent kept him in touch with his friends there, especially in Florence, Venice, and Rome, and in particular with the grandniece of James Fenimore Cooper, Constance Fenimore Woolson, the nearest to a true romance in his adult life. In May 1889 he met with a small group that included French critic Hippolyte Taine. James had written half a dozen pieces on Taine from 1868 onward. Taine's importance, he felt, rested on an attitude to fiction that resembled Balzac's and contributed to Zola's notion of the roman expérimental. Taine postulated the important influence of race, environment, and historical moment as determining the nature of a writer. What most touched James was that part of Taine's attitude that closely resembled his own notion of the importance of the psychological aspect. That is visible in Taine's introduction to his Histoire de la littérature anglaise: The "external man" is only a manifestation of the hidden, "internal man." After the luncheon James set down in his notebook something worth remembering: "Taine used the expression, very happily, that Turgenieff so perfectly cut the umbilical cord that bound the story to himself." James was then trying to learn to make a similar cut.

Theatrical Experiment (1891-1895)

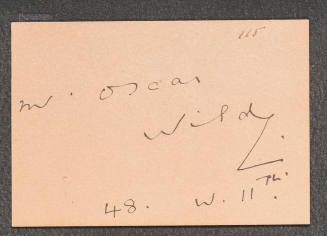

In 1891 The American succeeded in the provinces but was not well received in London. James had made it melodramatic and also provided a happy ending (which his friend and editor William Dean Howells had wanted for the novel). He had promised to give himself until 1895 to complete his experiment in the theater, and he wrote another six plays, only one of which was produced. Four of the others he published in 1894 as Theatricals and Theatricals Second Series. In December of that year he wrote prophetically to a friend, "I may be meant for the Drama--God knows!--but I wasn't meant for the Theatre." The theater was a horror for him: painful cuts in his scenarios, tiresome rewriting, long and onerous rehearsals, time limits imposed on productions, and the dull, insensitive audiences. Opening night of his next play, Guy Domville, on 5 January 1895 was a fiasco. The nervous James had gone to see another of Oscar Wilde's successes, An Ideal Husband, playing nearby. He returned to his own at curtain-fall and was then presented to a disturbed audience that hissed and booed. Several perceptive reviewers such as George Bernard Shaw, A. B. Walkley, and H. G. Wells praised the play, but it survived for only four weeks. James was shaken.

During the years of the theatrical experiment, James had published a series of tales of artists variously in conflict with the world, a continuation of his theme in The Tragic Muse. The series included "The Private Life" (1892); "The Real Thing" (1892), an instructive complement to "The Art of Fiction"; "The Middle Years" (1893); "The Death of the Lion" (1894); "The Coxon Fund" (1894); "The Figure in the Carpet" (1896); and perhaps most pertinent, "The Next Time" (1895), developed from the first entry in his notebooks after the theatrical fiasco. It tells the story of a respected but unpopular writer who tries to bend his artistic talent to the production of potboilers but always "fails." James had complained that writing for the British stage was like trying to make a sow's ear out of a silk purse; that is the theme of "The Next Time." The theatrical experiment was not a complete loss, James felt. He realized abundant compensation in the lesson "of the singular value for a narrative plan too of the . . . divine principle of the Scenario . . . a key that, working in the same general way fits the complicated chambers of both the dramatic and the narrative lock." He later called his discovery "the sacred mystery of structure."

The "divine principle" accounts for the techniques of most of his subsequent fiction, dramatic fiction free of the omniscient author. That role is often taken over by a character whose point of view ("angle of vision" rather than "opinion") controls the presentation; that feature is often accompanied by "reflexive characterization," which James had used as early as "A Bundle of Letters" (1878). In that tale the correspondents inadvertently expose themselves in letters they believe are recounting the news of the day. Reflexive characterization is illustrated in two major tales of 1898: "In the Cage," where the heroine exposes her own soul in the vicarious life she creates out of the materials of the telegrams she handles in her "cage," and "The Turn of the Screw," where the fascinating associations of two children with ghosts of two servants returned to win them to evil are almost entirely the projections of the rather disturbed psyche of the children's governess. The Sacred Fount (1899), James's only novel to rely on first-person narration, is a similar case of such projection. The technique achieves its culmination in The Ambassadors (1903). Novels of the period were planned out as though intended to be plays. Substantial notes for The Spoils of Poynton (1896) and for The Awkward Age (1899) show James's thinking in terms of acts and scenes. A bonus was the ease with which he could then revise a piece of fiction for the stage, or a play into a novel or tale.

Immediately after the failure of Guy Domville Ellen Terry asked James to write a play for her. In August 1895 he sent her the one-act Summersoft, which pleased her but which she never used. Three years later he recovered it and turned it into the tale "Covering End," and in 1909 it became the three-act play The High Bid. In 1893 James planned a new play for Edward Compton. It did not get beyond the note stage, but in 1896 he developed the note into the novel The Other House, which became a three-act play in 1909.

James was at Torquay in the fall of 1895 while his Kensington flat was being redecorated and having electricity laid on, yet he was already yearning for a house outside London. He spent the summer of 1896 in the home of Reginald Blomfield at Point Hill, Playden, on the north edge of Rye, Sussex. In August he moved into Rye proper ("The Vicarage") and discovered the old Georgian house with a generous garden called "Lamb House." He signed a 21-year lease the following year and in June 1898 took possession. It was his country house for the rest of his life. When his Kensington flat was sold, he was able to secure rooms in the Reform Club as his London "perch." He kept the Smith couple, who had served him in the flat, and added a houseboy, Burgess Noakes, and a maid, and gladly retained the services of George Gammon, the prize-winning gardener. Just five steps east of the house and inside the garden wall was a small structure called the Garden Room, where James worked in good weather; in winter he used the Green Room, on the second floor of Lamb House.

A New Series of Stories

Following the fiasco of January 1895 James had embarked upon a series of stories that featured children and young adults as though to reinforce his sense of starting over again; actually this was an intensification of an earlier trend. "The Pupil" (1891) tells of the precocious Morgan Moreen and his pretentious but impoverished family, who unload the boy onto his reluctant tutor. "Owen Wingrave" (1892) features dire family pressure--its military tradition resembles the political tradition of Nick Dormer's family in The Tragic Muse--which cannot accept young Owen's artistic and pacifist sentiments. What Maisie Knew appeared in the year James moved into Lamb House. It is the story of a little girl's efforts to comprehend the various combinations of parents and surrogates and their complex liaisons. "The Turn of the Screw" features the two children, Miles and Flora, thought by the governess to be pursued by evil spirits. Both "Owen" and "Miles" are names that mean "soldier" and similarly underline the adversarial situation in which they find themselves--and the similar ends they meet. The Awkward Age looks at two young women who are not quite ready to enter adult society but no longer young enough to be kept with the children. The novel develops its Blakean (Miltonic and Hawthornesque) theme of the importance of leaving Innocence, confronting the world of Experience bravely, and defining Evil clearly to oppose it and so achieve human maturity, as Isabel Archer had done in The Portrait of a Lady.

This series of fictions about the vulnerability of the young to the nefarious threats of the wide world matches closely the series published in the same period about similarly vulnerable and victimized writers. If James was working out his own sense of vulnerability via those two related series, then a sense of triumph over the threats emerges from The Awkward Age. The book's "happy ending," such as it is, brings together the young protagonist and a mature benefactor.

While working on What Maisie Knew, James suffered a severe attack of writer's cramp. Early in 1897 he hired William MacAlpine to take dictation in shorthand and transcribe it on a typewriter. He soon began dictating directly to MacAlpine as a typist. Henceforth James dictated much of his fiction and correspondence, having bought a Remington, the "music" of which he definitely preferred. Reliance on the typewriter somewhat curtailed his travel; "portable" machines were still in the future. That reliance may also have contributed to what some readers feel is James's prolixity and a tendency toward the baroque. Thus, while he did visit the channel coast in the summer of 1897, he did not get back to the Continent until early 1899. In February a serious fire in Lamb House gave him an urgent excuse to depart, and he traveled in Europe for several months.

James's Major Phase

On his return to England in July 1899, James learned that Lamb House was now for sale. He bought it for $10,000 and put up the Kensington flat (where his friend Jonathan Sturges had been living while James was on the Continent) for sale at once. He engaged James B. Pinker as his literary agent, and with the beginning of the new century he was set to create the three great novels of his Major Phase--The Wings of the Dove (1902), The Ambassadors (1903), and The Golden Bowl (1904)--and with them his second venture into biography, William Wetmore Story and His Friends (1903). His younger colleagues began to call him Master.

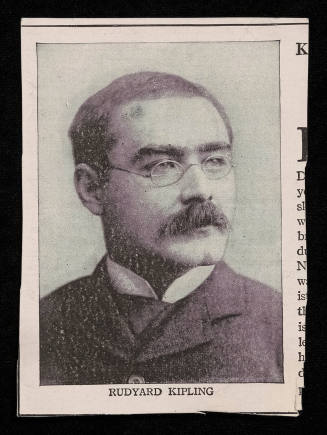

In the years clustered around the turn of the century James found himself at Lamb House in the center of a group of writers, mostly younger than he, who lived in the surrounding area: Joseph Conrad, Stephen Crane, Ford Madox Ford, Rudyard Kipling, and Wells. James could be a genial companion but was a severe critic. He told Mrs. Humphry Ward, "I'm a wretched person to read a novel--I begin so quickly and concomitantly, for myself, to write it rather--even before I know clearly what it's about!" Yet he was ready, especially in his later years, to give attention and encouragement to young writers whom he found promising. Among those were, most prominently, Wells, Hugh Walpole, and Edith Wharton. Another young writer, of modest success, deserves mention--Jonathan Sturges, often a guest at James's home. In 1889 Harper published his translation of thirteen tales by Maupassant, for which James had provided an introduction. In October 1895 Sturges went to Torquay to visit James and told him an anecdote about meeting Howells in Paris and being given by him some urgent advice: "Oh, you are young. . . . Be glad of it and live. Live all you can; it's a mistake not to." James made a note of it and thought there might be a story there but worried about the American-in-Paris cliché--"so obvious, so usual to make Paris the vision that opens his eyes." That is what he did, however, resuming after twenty years his old international theme in The Ambassadors. It is not The American retold. A comparison of Christopher Newman and Lambert Strether indicates the immense distance James's art had traveled in the interim.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Berdychiv, Ukraine, 1857 - 1924, Bishopsbourne, England

Steventon, England, 1775 - 1817, Winchester, England