Samuel Butler

Langar, England, 1835 - 1902, London

Butler, Samuel (1835–1902), writer and artist, was born on 4 December 1835 at the rectory at Langar, near Bingham, Nottinghamshire, the eldest son in the family of four children (including another son, Thomas, and two daughters, Henrietta and May) of Thomas Butler (1806–1886), rector of Langar from 1834 and canon of Lincoln, and his wife, Fanny (1808–1873), daughter of Philip John Worsley, a sugar refiner, of Arno's Vale, Bristol. He was the grandson of Dr Samuel Butler (1774–1839), headmaster of Shrewsbury School, and afterwards bishop of Coventry and Lichfield, whose Antient Geography Thomas Butler revised in 1851 and 1855. His aunt Mary, elder daughter of the bishop, was second wife of Archdeacon Bather.

Education and early life

These family details were of great significance in Butler's life, in that he was called on to continue a family tradition, as in part he did, by going to Shrewsbury, then under the headmastership of Benjamin Hall Kennedy, his grandfather's successor. He distinguished himself at the family college, St John's, Cambridge (1854–8), coming equal twelfth in the classical tripos, and later wrote the life of his grandfather. More importantly he rebelled against his family by refusing to take orders in the church, as unbelief grew in him while serving as lay reader at St James's, Piccadilly. He recorded his pained and satirical dissent from patriarchal Victorian hypocrisy in his major novel The Way of All Flesh.

Butler's first independent wish was to become an artist. He had been taught drawing at Shrewsbury by Philip Vandyck Browne, a friend and associate of the noted watercolourist David Cox, and had executed some still preserved landscape watercolours; and he had attended some classes at the Cambridge School of Art. This was anathema to his father who wrote, ‘The artist scheme I utterly disapprove. It will throw you into very dangerous company’ (Butler, Family Letters, 88–9). After much discussion it was agreed he should go to the colonies, and with approximately £4000 from his father try to make his fortune, after which he would be free to follow his own wish. His father clearly banked on ‘all that nonsense’ being knocked out of the young man on contact with ‘the real world’. Butler chose New Zealand, the most distant of colonies, and set sail from Gravesend aboard the Roman Emperor on 30 September 1859. He established himself as a sheep farmer in the Rangitata district of Canterbury Island, describing the new country in his letters home with contrasting references to the English and the European landscape that had made such an impression on him as an eight-year-old boy travelling abroad with his family, and recounting the adventure of his land claim with great vividness. His father had his letters published as A First Year in Canterbury Settlement (1863), with a preface by himself. Butler is now regarded as one of the early explorers of New Zealand, having crossed the Rangitata River, and narrowly missed the main pass through the mountains, as he described in the vivid opening to his utopian novel Erewhon, or, Over the Range. Butler did not confine himself to sheep farming, but played a considerable role in the cultural life of the colony, organizing the first art exhibitions at the Christchurch Club. He published his first pieces (apart from some slight essays in the St John's magazine The Eagle) in the local newspaper, the Christchurch Press, especially the witty speculation entitled ‘Darwin among the machines’, in which he imagined some consequences of the recently published Origin of Species.

Over the range and back: London and art

In 1864 Butler returned to England, having realized a tidy profit, and settled in rooms at 15 Clifford's Inn, Fleet Street, London. Although he was still not fully financially independent of his father, the bargain held, and he took up his career in art as a student first at F. S. Cary's in Bloomsbury, in the College of Art in South Kensington, and then at Mr Heatherley's well-known art school in Newman Street. His well-known painting Family Prayers (1864) may have been a response to his return to his constricted family circle; it is usually associated with The Way of All Flesh, which has a chapter describing such a scene. The art school's informal manner offered an escape. Mr Heatherley himself was the subject of Butler's best-known oil painting, Mr Heatherley's Holiday (1873), now in the Tate collection, depicting the genial head seated before the plaster casts of heroic antique statuary, mending a grotesque, frail skeleton with which the students performed the danse macabre at parties. There he met Eliza Savage, an independent and witty young woman in a day when there were few female art students, whose correspondence with Butler between 1871 and 1885 is one of the gems of the Butler literature. She encouraged him also in the direction of fiction, which he professed to detest. The correspondence ended with her early death in 1886. He also met the young Johnston Forbes-Robertson, then sixteen, afterwards the noted Shakespearian actor. Wearing the Heatherley's suit of armour, Forbes-Robertson is the subject of one of Butler's earliest known photographs, in the atmospheric style of the Pre-Raphaelite vogue in photography, and foreshadowing the future actor's role as Hamlet.

Forbes-Robertson left an affectionate memoir of Butler, showing him as a diligent student, but one with time for ‘happy daily hob-nobs’ over lunch at the Horseshoe pub. He notes that Butler was keen to be accepted as a student at the Royal Academy; but Butler's submissions did not lead to his acceptance, though he had at least eleven paintings hung in several exhibitions, including Mr Heatherley's Holiday in 1874. J. B. (Jack) Yeats, at Heatherley's in the previous decade, wrote respectfully of Butler's ‘emancipated intellect’, but dismissed his attempts to paint in a ‘Bellini-like’ style, as proposed by Ruskin, whose Seven Lamps of Architecture had impressed Butler as an undergraduate. Butler later adopted a satirical, even bitter view of the Pre-Raphaelite circles, but a number of Ruskinian aims continued to play a role in his thinking. He also met Charles Gogin, later a successful illustrator, who remained a life-long friend, and painted the portrait of Butler now in the National Portrait Gallery.

Butler's literary reputation always eclipsed his work as an artist. In 1872 he published Erewhon anonymously, to considerable acclaim. This searching and novel utopia was based on a map of an imaginary country inserted into the map of the New Zealand district he had explored. An interest in fictional maps is visible again in his later invention of a new version of the periplus of Odysseus, and in his fascination with the mapping of the geography of Jerusalem onto the Alps that characterized the site of the Sacro Monte at Varallo. This preoccupation may owe something to the classical atlas he saw his father revising when he was a schoolboy. His imaginary society undoubtedly arose from his close scrutiny of the ethical implications of Darwinism, one of the earliest such considerations. He locates the central point in a ‘Nowhere’ whose citizens are criminalized and punished for contracting and concealing disease, whereas traditional ‘sins’ and moral failings are cheerfully acknowledged and accepted. This highlights the question of whether ‘criminals’ are responsible for their crimes; are the causes of crime not what would now be called ‘genetic’? And if so, is the self-righteousness of pastors and masters justifiable? In the famous chapter ‘Book of the machines’, with its museum of the technological innovations Erewhon had banned, Butler foresaw that technology would become overmastering, and that it would have to be controlled. As in all his best work, his topsy-turvy world produces shock, biting humour, and a provocation to fundamental rethinking.

Butler's next book, The Fair Haven (1873), like his essay entitled ‘The evidence for the resurrection of Jesus Christ as given by the four evangelists critically examined’ (drafted in New Zealand, published anonymously in 1865), pressed further on the religious assumptions and claims still being clung to by the churches. It is one of his most complex and least understood books; it purported to be a defence of the miraculous element in Christianity, as edited by William Bickersteth Owen, the brother of the deceased ‘author’ John Pickard Owen, but it was intended to undermine the proposed views. The chapter ‘The Christ ideal’ was an oblique attack on current aesthetic substitutes for religion. Formally, it was a subtle deployment of the persona of ‘the editor’ as developed in the higher criticism of the Bible and in recent fiction. It was, however, taken at face value, and Butler was forced to reveal his authorship and his subversive intention. As the gullible critics had been taken in, they took their revenge in negative reviews.

Evolutionary wits: writings on Darwin and Darwinism

Butler pursued his reflections on Darwin and Darwinism in Life and Habit (1878), Evolution, Old and New (1879), Unconscious Memory (1880), and Luck or Cunning? (1886). He deserves a more considerable place than he has gained in accounts of Darwin's reception: in English histories of evolutionary thought he is often dismissed as merely idiosyncratic. (An unfortunate personal element entered, when he felt, wrongly, that Darwin had slighted him.) But in France, Butler's Lamarckist interests in the role of forms of heritable memory of experience valuable in the ‘survival of the fittest’ were welcomed, and his French translators and commentators saw him as an important figure in the history of ideas. George Bernard Shaw was also much influenced by Butler's thinking, and the evolutionary explorations in his plays, most explicitly in Back to Methuselah, as well as his social thinking, owe much to Butler, a debt Shaw gladly acknowledged. Butler is due for renewed attention, especially in light of recent developments in molecular biology which make a reconsideration of the subtler modes of inheritance and transmission possible.

Butler's altercations with his father were not yet over. Perhaps the worst of them came in 1879 as a result of his father's discovery that over the years Butler had been giving money to Charles Paine Pauli, a charming rogue whom he had met in New Zealand and who had returned to England at the same time. It emerged at Pauli's funeral in 1897 that he had had a number of such supporters; a late note by Butler reveals his shock. His own financial situation had deteriorated, and he was obliged to travel to Canada, where he had invested his New Zealand gains, to try to put matters right. He felt he had misled Pauli in advising him on investments. His father's discovery of his misplaced generosity or what he construed as an egregious instance of financial mismanagement, and his horror at what this relationship might signify in his unmarried son's life, led to further threats that financial aid would be withdrawn. Finally, however, the elder Butler died in 1886, and Butler came into his inheritance. From that time forward he spent half the year in Italy at Faido and then at Varallo, where he felt both free and at home.

Italian journeys: Alps and sanctuaries

Butler's productive travels in Europe, especially Italy, had already begun, and in 1881 he published Alps and Sanctuaries, the lively account of his travels to the sanctuaries of the Ticino, Piedmont, and Lombardy. His French translator, Valéry Larbaud (also Joyce's translator), praised his appreciations of Italy, which he rated higher than those of his own countrymen. Amusing and readable, illustrated with Butler's own sketches and paintings, they also had a serious purpose: the rehabilitation of the sites and artists of the Counter-Reformation, the objects of popular Catholic pilgrimage, but ignored by aristocrats on the grand tour, by the new middle-class tourists, and by the connoisseurs and art historical specialists. He takes up cudgels for a form of art distasteful to the sectarian narrowness and class prejudices of his own family and many of his countrymen. Here he pursues Ruskinian themes in a novel context—the work of anonymous or little known craftsmen who contributed to the pilgrimage sites of Varallo, Varese, Oropa, and Crea—and uses the local villagers as models and pilgrims as participants in a sacred visual drama of events from the life of Jesus or Mary. Having despaired of making a conventional career in art, he successfully brought together his literary and his artistic gifts in Ex voto: an Account of the Sacro Monte or New Jerusalem at Varallo-Sesia (1888). Ex voto focused on Varallo, the founding site, and contained Butler's most original and sustained contribution to art history, his exposition of the chapel art of Varallo, and his pioneering rediscovery of the work of Gaudenzio Ferrari, painter and major sculptor of the life-size figures of the chapels at Varallo, and several more minor figures such as Tabachetti and the D'Enrico brothers, Giovanni and Antonio (better known as Tanzio da Varallo). While he lauded the unsung craftsmen, he also individualized them and drew their œuvre into art history. When the Sacro Monte of Varallo celebrated in 1986 the 500th anniversary of its founding, there was a special exhibition of Butler's letters to and from his many friends in Varallo, with whom he corresponded in Italian, together with one of his paintings of the site.

Only a fraction of Butler's explorations of these themes could be published in the books themselves. He revisited them in depth in the series of paintings, sketches, and photographs of the routes he travelled, the towns and their artworks. The photographs are especially revealing. Butler and his assistant Alfred Cathie preserved a selection of his snapshots in albums left to St John's College, also the repository of the original glass negatives; his most prized album, with large photographs relating to the Sacro Monte, was sold to the Chapin Library at Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts. The full range and substance of this joint work of literary and visual art came to light only in the late twentieth century with Elinor Shaffer's Erewhons of the Eye: Samuel Butler as Painter, Photographer and Art Critic (1988) and a related travelling exhibition of 1989–90. In 2002, the centenary of his death, St John's College, Cambridge, and Tate Britain held further exhibitions of his photography. The academy reject, the maverick applicant for the Slade professorship (1886), became a pioneer of a new art form.

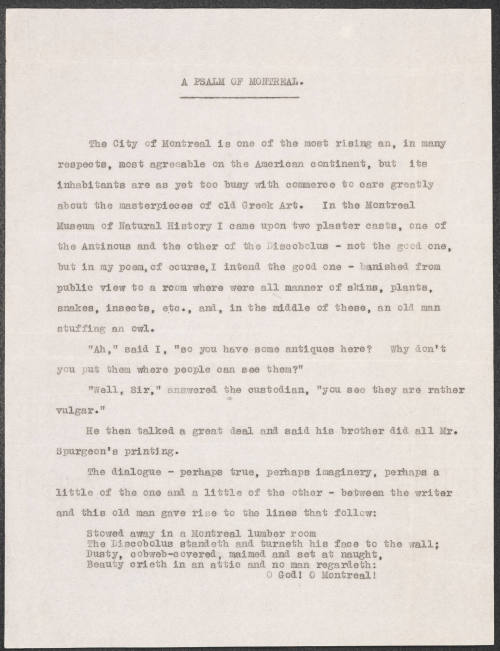

Classical worlds: new topographies

Butler's originality and irreverence were expressed again in the other group of works he published in the 1890s, on the classics. No one could go as unerringly to the heart of Victorian prejudices as he. The very title of his book The Authoress of the Odyssey (1897) was calculated to offend the entire establishment nurtured on Gladstone's notion that a classical education, a grounding in the political and military tactics of Homer's Iliad and the navigational prowess of the Odyssey, was the best preparation for young men whose task was to rule the empire. Butler's sly claim that the Odyssey was essentially a domestic tale, the locations were limited to Sicily, the sailing instructions obscure, the adventures told only in recital at the dinner table, summed up in the bold surmise that the author was a woman, had, and even today still has, the desired effect. His project as usual was backed by a variety of related enterprises, in particular his fluent colloquial prose translations of the Iliad (1898) and the Odyssey (1900), which broke down the stilted pseudo-archaic ‘high’ style of translation then in vogue and deliberately, as he said, aimed at an ideal audience of young girls uneducated in the classics who would be caught up in the story. No other work of his received such extensive or more strongly divided reviews. Nor did he fail to carry his investigations into the field, trekking to Asia Minor to view the site of Schliemann's excavations of Troy, taking in the Greek sites en route, and photographing along the way.

As usual, Butler was not just being mischievous, but was giving vivid expression to the current state of scholarly controversy. There was a long tradition supporting the position that the Iliad and the Odyssey were not written by the same hand, and that the former was centred on war and male pursuits, the latter on domestic and female pursuits. Moreover, since the work of F. A. Wolf at the end of the eighteenth century there had been an important critical shift towards the view that the Homeric texts were in any case not written by one author, but were the result of several centuries of oral poetry relating to the events at Troy, brought together in the sixth century BC by a group of editors. There was no single Homer, the ‘blind bard’ of tradition, and this continued to be the dominant view of scholars in the twentieth century. The Victorian defenders of the unity and greatness of Homer, however, tended to indulge, like Gladstone, and Matthew Arnold, in praise of the ‘grand style’ and the patriarchal interest. Butler took the most direct route to casting doubt on their values and their grandiloquence when he claimed that their canonical author was in fact a woman. Moreover, Butler presented a photographic record of Sicily as the home of the ‘authoress’. It was increasingly held that the classical world of the Odyssey was no longer the grand Mycenaean civilization of the time before Troy fell, but the shrunken and impoverished world of the centuries after the Trojan war. Butler's Sicilian photographs accordingly give the flavour of the small, domestic scale of Ulysses' holdings through shots of local sailing boats, dusty courtyards, and farm animals, sleeping men, and especially Circean pigs. These literary reinterpretations intersect with a finely observed current Sicilian landscape. His notable contributions to modernism are again discernible—James Joyce made the argument that the Odyssey was ‘domestic’ his own, reducing the Authoress's journey round Sicily to Bloom's day in Dublin. Paradoxically, Butler's ironic work also gave rise to a succession of modern attempts, by Victor Bérard, the noted French classical scholar, and Jean Bérard, Ernle Bradford, and Tim Severin, to sail in replicas of ancient ships along the routes of the Odyssey and to photograph the landfalls.

Last things

In Shakespeare's Sonnets Reconsidered (1899) Butler's argument that the male object of Shakespeare's interest in the sonnets was a lower-class ‘Mr WH’ was undoubtedly a gesture of solidarity with Oscar Wilde, tried and imprisoned for a similar interest. There were a number of such gestures at the time, more or less explicit. The ironic championing of the obscure love object of the popular dramatists Shakespeare and Wilde was related to Butler's concern for the little regarded popular artists of the Sacro Monte and their models. In Erewhon Revisited (1901) the protagonist, who had succeeded in escaping from Erewhon by balloon, returns to find to his astonishment that he has been made the centre of a new religious cult, based on the ‘miracle’ of his ascension. This enables Butler to analyse the phenomena of religion from their point of genesis, while disclaiming all responsibility for their uncanny parallels to certain known religions. In thus returning to the beginnings of his writing career, he showed that his wit and his scepticism were as fresh as ever.

Butler's longest-standing friendship was with Henry Festing Jones, whom he regularly visited when in London, and with whom he sometimes travelled. They tried their hands at writing music, first Handelian minuets and gavottes, then an oratorio buffo, Narcissus (1888). They studied counterpoint with W. S. Rockstro, and designed a Ulysses oratorio (published in 1904). It has been said that for twenty years they shared the favours (for a consideration) of the same woman, on different days of the week. Butler was also accompanied to the end of his life by Alfred Emery Cathie, who had been employed in 1882, at the age of twenty-two, as his valet and clerk, and who became his photographic assistant and his companion.

Samuel Butler fell ill (doctors disagreed on the cause of the malfunction of the digestive tract) and died in St John's Wood Road, London, on 18 June 1902. He had remarked that evening, when Jones, unusually, paid a second daily visit, that it was ‘a dark morning’. This small, bookish man, who nevertheless had a strong streak of the intrepid explorer of new worlds about him, was by his own choice cremated at Woking, and his ashes were buried in an unmarked grave. His will appointed his cousin Reginald Worsley his executor and R. A. Streatfeild his literary executor, and stipulated that his pictures, sketches, and studies were ‘to be destroyed or otherwise disposed of as they may think best’, while Jones was to have ‘all interest in musical compositions upon which they had been jointly engaged’. Alfred Cathie was to have £2000, his personal effects, and his photographic cameras.

Afterlife: The Way of All Flesh

It was the posthumous publication of The Way of All Flesh (1903), however, that firmly established Butler's reputation. This powerful autobiographical work was started in the early 1870s but put away in 1884, two years before his father's death, as he felt that its publication would offend his family (his two surviving sisters were in fact unhappy about it). Had it been published at the time of writing, it would undoubtedly have received a less enthusiastic welcome than it did in the wave of anti-Victorian sentiment that characterized the years after his death. But this uneasy position between two periods has meant that literary scholars and critics of modernism have often remarked on its warm reception, but not in detail on its qualities as fiction, because they felt it belonged to the Victorian period, whereas the Victorianists saw it as falling outside their scope because it was published and received only in the modernist period. Thus it had strong affinities with nineteenth-century fictional forms and concerns, as a Bildungsroman, or novel of education, like Goethe's or George Eliot's, and as a study of the loss of religious faith, where comparisons would be to Carlyle and Mrs Humphry Ward. Yet those to whom he spoke most powerfully were not his coevals in fiction, Hardy and Meredith, nor those who came to modernism via aestheticism and decadence, but Shaw, Graves, Forster, Lawrence, Strachey, Wyndham Lewis, and Joyce, and critics like William Empson, heir to his provocative, ingenious, and witty criticism, as well as to men of letters abroad, especially in France. Quite possibly a new, comparative approach is required, looking at Butler's four works of fiction in the context of late nineteenth-century European naturalism as the stepping-stone to modernism. The status of The Way of All Flesh is undisputed, however, and like Erewhon it has remained in print without intermission.

Festing Jones advised the executors on the disposition of Butler's estate, and became his first biographer, and the first editor of his notebooks, as well as author of some other pieces about him, including Darwin and Butler: a Step towards Reconciliation (1911) and an account of their travels in Sicily. Jones proved a judicious and assiduous adviser, who did his best to place Butler's manuscripts, paintings, photographs, and personal objects in the repositories most appropriate to them: the early watercolours to Shrewsbury School, the bulk of the materials to St John's College, paintings and letters to his New Zealand sitters and correspondents. Butler had himself given away large numbers of his paintings during his lifetime. Jones's biography of Butler (Samuel Butler, Author of Erewhon, 1919) was bulky but anecdotal. His best memorial to his friend was his selection of Butler's pithy observations, The Note-Books of Samuel Butler, which proved another substantial addition to Butler's reputation when the book appeared in 1912. It still stands its ground against the later selections and the one volume (of five projected volumes) of the modern edition of the notebooks, deftly capturing and juxtaposing Butler's variously passionate, shrewd, quirky, and surprising insights.

Elinor Shaffer

Sources

The note-books of Samuel Butler, ed. H. F. Jones (1912) · Further extracts from the note-books of Samuel Butler, ed. A. C. Bartholomew (1934) · Samuel Butler's notebooks: selections, ed. G. Keynes and B. Hill (1951) · Letters between Samuel Butler and Miss E. M. A. Savage, 1871–1885, ed. G. Keynes and B. Hill (1935) · The note-books of Samuel Butler, ed. H.-P. Breuer, 1: 1874–1883 (1984) · The family letters of Samuel Butler, 1841–1886, ed. A. Silver (1962) · The correspondence of Samuel Butler with his sister May, ed. D. F. Howard (1962) · Butleriana, ed. A. C. Bartholomew (1932) · S. Butler, A first year in Canterbury settlement, ed. T. Butler (1863) · P. Raby, Samuel Butler: a biography (1991) · H. F. Jones and A. T. Bartholomew, The Samuel Butler collection at St John's College, Cambridge: a catalogue and a commentary (1921) · Samuel Butler (1945) [catalogue of the collection in the Chapin Library, Williams College, Williamstown, Mass.] · E. Shaffer, Erewhons of the eye: Samuel Butler as painter, photographer and art critic (1988) · The life and career of Samuel Butler (1967) [handlist of an exhibition held at Chapin Library, Williams College, Williamstown, Mass.] · Samuel Butler: a 150th birthday celebration (1985–6) [handlist of an exhibition held at Chapin Library, Williams College, Williamstown, Mass., 1985–6] · Samuel Butler and his contemporaries (1972) [catalogue of an exhibition held at the Robert McDougall Art Gallery, Christchurch, New Zealand] · Samuele Butler e la Valle Sesia (1986) [handlist of an exhibition held at the Biblioteca Civica Farinone-Centa, Varallo-Sesia] · Samuel Butler (1835–1902): the way of all flesh: photographs, paintings, watercolours and drawings (1989–90) [exhibition catalogue, Bolton Museum and Art Gallery; Royal Museum and Art Gallery, Canterbury; D. L. I. Museum and Art Centre, Durham; University Art Gallery, Nottingham] · The artist's model from Etty to Spencer, ed. M. Postle and W. Vaughan (1999) [exhibition catalogue, York City Art Gallery; Kenwood, London; Djanogly Art Gallery, U. Nott.] · Samuel Butler (1835–1902): centenary exhibition (2002) [exhibition catalogue, St John Cam.; handlist and notes by E. Shaffer] · Samuel Butler (1835–1902): photographs (2002) [exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London, Nov 2002 – June 2003]

Archives

BL, corresp. and papers, incl. literary MSS, Add. MSS 36711–36713, 38176–38177, 39846–39847, 44027–44054 · BL, notebook, Add. MSS 71695 · Canterbury Museum, letter-book and sketchbook · St John Cam., papers incl. sketches, drawings, and paintings; extensive photographic holdings, including original glass negatives and albums · Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts, Chapin Library of Rare Books, corresp. and literary papers, paintings and drawings, ‘Sacro Monk’ photographic album :: Bodl. Oxf., corresp. with Robert Bridges · CUL, letters to Charles Darwin and related papers · CUL, letters, mainly to Henry Festing Jones

Likenesses

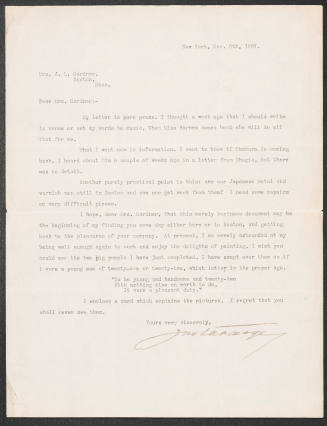

S. Butler, self-portrait, 1873?, NL NZ, Turnbull L. [see illus.] · A. Cathie, photograph, 1890, St John Cam. · C. Gogin, oils, 1896, NPG · S. Butler, self-portrait, Shrewsbury School · S. Butler, self-portrait, St John Cam. · photograph, NL NZ, Turnbull L. · photographs, St John Cam. · photogravure (aged fifty-four), BM

Wealth at death

£33,076 18s. 6d.: resworn probate, Jan 1903, CGPLA Eng. & Wales (1902)

© Oxford University Press 2004–16

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Elinor Shaffer, ‘Butler, Samuel (1835–1902)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/32217, accessed 10 Oct 2017]

Samuel Butler (1835–1902): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32217

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Walmer, England, 1844 - 1930, Oxford, England

Kolkata, India, 1811 - 1863, London

Putney, England, 1844 - 1910, Weybridge, England

Ware, England, 1856 - 1916, London

St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana, 1818 - 1893, New Orleans, Louisiana

Partick, Scotland, 1872 - 1948, Monte Carlo

Germantown, Pennsylvania, 1860 - 1938, Saunderstown, Rhode Island