Kate Greenaway

London, 1846 - 1901, London

Childhood and education

Greenaway's father was a wood-engraver; and the irregularity of his income led her mother to open a successful milliner's shop in Islington in 1851. It was here that most of Kate Greenaway's childhood was spent, often in the care of her elder sister, as her sternly respectable and somewhat humourless mother worked long hours. She was fascinated by the shops and entertainments of London, but was still more happy when on holiday with relatives in Rolleston in Nottinghamshire: many of her early watercolours depict the scenes and people of this quiet village. Shy yet temperamental, she was unhappy at the dame-schools to which her mother sent her and was largely educated by private tutors. Her favourite childhood activities reflected her vivid and emphatically visual imagination: she built up a large collection of dolls, around which she wove fantasies, and enjoyed looking at the illustrations of the leading periodicals and attending the theatre.

At the age of twelve Greenaway was enrolled as a full-time student at the Finsbury School of Art, where she had already taken evening classes. Here she studied for six years, completing the national course of art instruction initiated by Henry Cole to train designer craftsmen: the course's emphasis on linear design and geometry clearly influenced the patterned effect of her later illustrations. In 1865 she moved on to the National Art Training School in South Kensington, where she spent at least six years. Her shyness meant that she made few friends there, but among them was the painter Elizabeth Thompson, afterwards Lady Butler. She later attended the Heatherley School of Fine Art and enrolled at the Slade School of Fine Art: both institutions advocated a less rigid approach to drawing and painting than Cole's school, but Greenaway found it difficult to modify her detailed and imitative style.

Early career as a book illustrator

In 1867 Kate Greenaway's first book illustration—the frontispiece to Infant Amusements, or, How to Make a Nursery Happy—was published, clearly influenced by the style of John Leech and John Gilbert, book illustrators who worked within the picturesque and caricaturist style of the 1830s and 1840s. In the following year she exhibited drawings publicly for the first time, at the Dudley Gallery. In 1869 she received an important commission to produce six watercolours to illustrate Diamonds and Toads, a children's book published by Frederick Warne. By 1870 she had earned over £70 through book illustration, and her career was launched, with commissions secured for her by her early patron, William Loftie, and her father. She had also started designing cards for Marcus Ward & Co., her images ranging from delicate images of fairies and goblins to Pre-Raphaelite-inspired lovers.

In 1877 Greenaway broke with Ward & Co., who were using her card designs in books without consulting her; she was also driven by the desire to write the letterpress for her own illustrations (Ward had rejected the poems she had submitted with some of her designs). Her father approached Edmund Evans, with whom he had formerly worked in Ebenezer Landells's workshop and who now owned and ran a very successful colour-printing firm, producing many children's books. Evans liked her odd nonsense verses and their accompanying designs, and agreed to publish a book, Under the Window (1879). She became a close friend of the Evans family and a frequent visitor to their home at Witley in Surrey. Through Evans she was introduced to Randolph Caldecott, a fellow illustrator of children's books, and the society poet Frederick Locker, who was asked to amend some of her verses.

By 1879 Greenaway's income was large enough to allow her to pool resources with her father and buy a new house, 11 Pemberton Gardens, Holloway, for the family. She began illustrations for Charlotte Yonge's The Heir of Redclyffe and Heartsease: although she succeeded in capturing the sweetly insipid character of Violet, the heroine of Heartsease, these illustrations are among her worst, and they rightly confirmed her in her preference for illustrating her own text. She never completed this commission from Macmillan, but the runaway success of Under the Window—sales of which reached 100,000 copies in Greenaway's lifetime—had ensured her career. Her delicate and economical designs, her genius for the use of blank spaces, and her ability to dovetail her images to her text are all apparent in this book, which attracted artistic attention to her work. The Royal Academician Henry Stacey Marks offered well-meaning criticism of her treatment of feet, and Walter Crane—who described her book as ‘old world atmosphere tinted with modern aestheticism’ (Engen, 1981, 61)—was alarmed by the popularity of his new rival's work.

Relationship with Ruskin

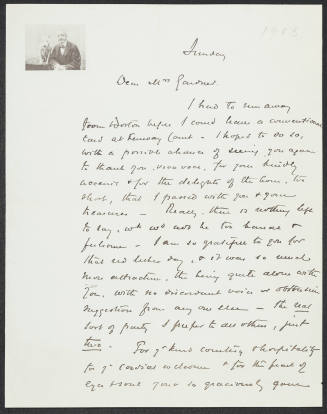

Through Marks, Greenaway was introduced to the ageing Ruskin, who found that her images of young girls ministered to his obsession for Rosa La Touche. He wrote her an extraordinarily impertinent letter on 6 January 1880, to which she responded warmly. She was swiftly adopted as one of his circle of female art protégées (E. E. Kellett later recalled how Ruskin brought fifty of her pictures to one of his Slade lectures and passed them round), and their correspondence continued for some twenty years, the lion's share falling to Kate. She was becoming an artistic celebrity and lost much of her erstwhile shyness: in the 1880s she became friends with Anna Thackeray Ritchie, the Tennyson family, and other literary lions.

In the autumn of 1880 Greenaway published Kate Greenaway's Birthday Book, a collection of illustrations which was an instant success. Mother Goose, or, The Old Nursery Rhymes, F. Locker-Lampson's London Lyrics, and A Day in a Child's Life followed in 1881, and the first of her illustrated almanacs appeared in 1883; 1884 saw the publication of a new edition of an old classic, William Mavor's The English Spelling Book, with Greenaway's illustrations, and an illustrated book of verses, Marigold Garden. Strongly influenced by eighteenth-century art, particularly the paintings of Gainsborough, and her most expensive book to date, this last was rather poorly received.

In the same year Greenaway spent a fortnight with Ruskin at Brantwood, and their friendship deepened. His lecture of that year, ‘In fairyland’, praised Greenaway and Helen Allingham for revitalizing the essential Greek spirit of fancy through their work. Nevertheless, he constantly advised her to undertake close studies of nature and to improve her grasp of anatomy, to adopt a more naturalistic yet neo-classical approach to her art. In one year her Christmas card to Ruskin of a wide-eyed girl led the critic to comment, ‘To my mind it is a greater thing than Raphael's St Cecilia’ (Engen, 1981, 76), an apparent absurdity which illustrates his intention to make Greenaway elevate her art. She took his advice very seriously, spending a week in Scarborough drawing after he had advised her to go to a seaside town to learn how to draw children's naked feet. Her work also occasionally showed the influence of the academic neo-classicists, such as Lord Leighton and Sir Edward Poynter; the frontispiece to A Day in a Child's Life, for instance, is reminiscent of Albert Moore.

By late 1883 Ruskin was alarmed by the degree of Greenaway's personal devotion—although still transfixed by the streams of drawings of young girls she sent to him (always clothed and often behatted, to his disappointment). He put off her visits to Brantwood, ignored her when he took tea at her house (concentrating all his attention on one of her models, Mary), and was a severe critic of The Language of Flowers (1884), an illustrated book on flower symbolism which she had produced under his influence.

1880s: Hampstead days

In 1883 Greenaway moved to Hampstead, and in 1885 she bought 39 Frognal, a house which was designed for her by Norman Shaw, the leading architect in the Queen Anne style. The house contained an extensive studio, which she decorated in an aesthetic mode, and a garden, which she planted informally with traditional cottage flowers. She began to consider the possibility of abandoning book illustration in favour of painting—a course which seemed particularly tempting in view of the growing number of Greenaway imitators and the influence of Ruskin—but was still not prosperous enough to break her connection with Evans. Buoyed up by the high spirits which normally preceded a return of his periodic insanity, Ruskin collaborated with her to produce the decidedly undistinguished Dame Wiggins of Lee (1885), a revamped version of an early nineteenth-century children's story in verse. In July of that year she visited Brantwood, but departed as Ruskin's illness advanced.

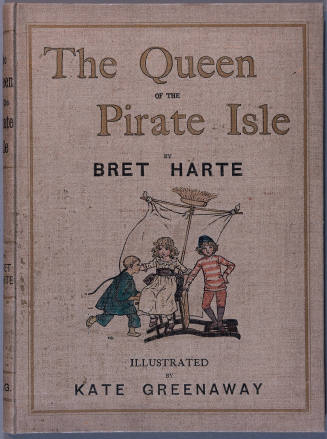

The next few years proved bleak, with Ruskin either suffering fits of madness or absorbed in writing his autobiography, Praeterita. Greenaway's reputation was in decline in Britain (although sales of her work in America were buoyant). She continued to produce her almanacs and also illustrated Bret Harte's The Queen of the Pirate Isle (1886) for Chatto and Windus, a rare departure from her connection with Evans. In 1887 she illustrated Robert Browning's Pied Piper of Hamelin (1888) in a Pre-Raphaelite style. It is possibly her best work. The frontispiece is an accomplished and complex design with a beautifully rendered cherry tree at its heart, suggestive of Japanese influence as well as Greenaway's delight in English springs. The illustrations inside, meanwhile, are handsomely married to the text; the statuesque townsfolk, the Dantesque piper, the mastery of perspective (Ruskin's influence is apparent) and picturesque architectural settings, and the limited autumnal range of Greenaway's palette—all olive greens, pale teal blues, russets, browns, and salmon pink—contribute to make it one of the best illustrated children's books of the Victorian period.

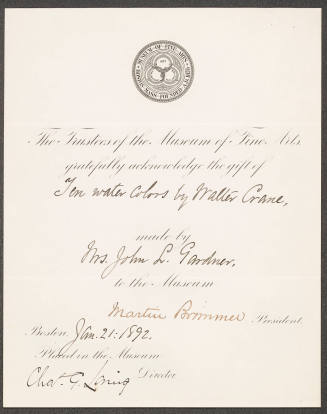

Greenaway—as well as Ruskin—was unwell in the later 1880s, and she called in the physician Elizabeth Garrett Anderson to treat the first of a continuing series of colds, influenza, and rheumatic pains. Rather more cheeringly, in 1888 she spent much time with Helen Allingham at Witley, and was influenced by both her artistic ambitions and her robust attitude to Ruskin. In 1889 she turned down an invitation to Brantwood to embark on a series of watercolours for exhibition, inspired by Allingham's success and often joining her new companion on painting trips to the countryside. She sent thirteen of her original book illustrations to the Paris Universal Exhibition, where they met with considerable success, and she was elected to the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours. Her correspondence with Ruskin—often intermittent on his part—now ceased, and she turned to his cousin and companion Joan Severn for friendship and news.

Photographs of the younger Kate Greenaway show that she was always a rather plain woman—even the kindly Caldecott conceded that she was ‘not beautiful’ (Yours Pictorially: Illustrated Letters of Randolph Caldecott, ed. M. Hutchins, 1976, 38)—and in middle age she became stout. But, despite her stumpy nose, her deep-set dark eyes had—according to her early patron, William Loftie—‘a certain impressive expression’ (Engen, 1981, 46), which must have been all the more striking as, with advancing age, her eyebrows became increasingly marked.

The 1890s: new directions

Greenaway's publications of 1889—The Royal Progress of King Pepito and Kate Greenaway's Book of Games—were not commercially successful, and she was obliged to sell an earlier picture, Bubbles (version, V&A), to the soap manufacturer Pears to be used as an advertisement. In 1890 her father died, leaving his family in some financial distress. Greenaway rose to the occasion, arranging a joint exhibition (with Hugh Thomson) of her old paintings and drawings at the Fine Art Society in 1891: sales of her work raised £964. But her health was declining, and enjoyable holidays in Bournemouth and Cromer with friends (the Ponsonbys and the Locker-Lampsons) failed to restore it. She continued to work towards another exhibition of her work at the Fine Art Society in early 1894. As at the previous exhibitions, both critics and buyers continued to prefer her earlier work to the larger and more ambitious watercolours which were now the staple of her output. Her mother's death in February 1894 caused her to stop working altogether for a couple of months, but she began to recover later in the year, paying visits to the invalid Ruskin in 1894 and 1895 and visiting London galleries, where she was equally, though differently, alarmed by Aubrey Beardsley and the impressionists. She viewed her own work now as a solitary attempt to maintain the artistic standards of the high Victorian Renaissance.

In 1895 Greenaway met and began a close (but probably not lesbian) relationship with Violet Dickinson, better known as the lover of Virginia Woolf. A robust personality, she ensured that Greenaway turned out for social occasions and cultural events and introduced some colour into her sober and shabby style of dress. During the late 1890s Greenaway continued to exhibit her watercolours, without much critical success. An exhibition at the Fine Art Society in 1898 was decidedly low-key, and Greenaway became increasingly reliant on wealthy patrons who were often also friends, such as Lady Dorothy Neville. She experimented with portraits of children in oils, began an autobiography which was never finished, resumed writing soothing letters to Ruskin, and planned to return to book illustration. She illustrated one last book: Elizabeth von Arnim's The April Baby's Book of Tunes (1900). In that year Ruskin died, a devastating blow for Greenaway. She was already suffering from breast cancer, a condition which she concealed from friends and family. In July 1900 she had an operation, but the cancer had now spread to her chest. She died at her home, 39 Frognal, Hampstead, on 6 November 1901; her body was cremated at Woking on 12 November, and on the following day her ashes were placed in the family plot in Hampstead cemetery.

Reputation and achievement

A posthumous exhibition of Greenaway's work was held at the Fine Art Society in 1902, a biography by Marion Spielmann and G. S. Layard appeared in 1905, and a Greenaway memorial fund was established. Her reputation flourished on the continent and in America, but it was not until the 1920s that it revived in Britain as collectors began to buy her work. The centenary of her birth led to a spate of new articles and books, and in 1955 the Kate Greenaway medal was established as an annual award for an outstanding illustrator of children's books. Reprints of some of her books have continued into the twenty-first century, her images have appeared on greetings cards, and her original drawings and first editions of her books have continued to fetch high prices in salerooms.

Despite all Greenaway's attempts to pursue the Ruskinian path of high art, both her popularity and her achievement really rest on her work as one of the three great illustrators of children's books in the mid-Victorian period. Her work clearly owes a debt, as contemporaries suggested, to the delicate engravings of Thomas Stothard. The illustrators of her own age with whom she is often compared are Walter Crane and Randolph Caldecott: with them, she promoted the Queen Anne style, a major facet of the aesthetic movement in the 1870s and 1880s. In her idyllic and profoundly nostalgic depictions of vaguely eighteenth-century and slightly stilted children, Greenaway combined strong outlines and a keen ability to arrange and pattern space with the use of a palette of soft, silvery pastel colours (it was not her fault that printers occasionally rendered these colours too crudely). Undoubtedly her range of subjects was narrow, and her illustrations lack both the sophistication of Crane's elaborate images and the visual wit and talent for characterization apparent in Caldecott's work. Nevertheless, as Percy Muir has put it, ‘she created a small world of her own, a dream-world, a never-never-land’ (Muir, 170) which appealed as much to adults as to children. It was a world that continued to be popular: the work of Hugh Thomson and the Macmillan ‘Cranford’ school adhered to the Greenaway tradition in the age of Beardsley. Mark Girouard nicely captures the modern commentator's ambiguous reaction to her illustrations: ‘Many people, when looking through her books, must find revulsion from so much sweetness and quaintness fighting with admiration for her extraordinary skill’. But, he concludes, ‘she is a minor master’ (Girouard, 146).

Rosemary Mitchell

Sources

R. Engen, Kate Greenaway (1981) · M. Spielmann and G. S. Layard, Kate Greenaway (1905) · M. Girouard, Sweetness and light: the ‘Queen Anne’ movement, 1860–1900 (1977) · DNB · I. Taylor, The art of Kate Greenaway: a nostalgic picture of childhood (1991) · W. Ruddick, Kate Greenaway, 1846–1901 (1976) [exhibition catalogue, Bolton Art Gallery, 1976] · The reminiscences of Edmund Evans, ed. R. McLean (1967) · T. E. Schuster and R. Engen, Printed Kate Greenaway: a catalogue raisonné (1986) · R. Engen, Kate Greenaway (1976) · P. Muir, Victorian illustrated books (1985) · J. I. Whalley and T. R. Chester, A history of children's book illustration (1988) · M. Hardie, English coloured books (1906) · b. cert. · CGPLA Eng. & Wales (1901) · E. E. Kellett, As I remember (1936)

Archives

Boston PL, letters · Keats House, Hampstead, London, original drawings, proofs, Christmas cards, and books · Morgan L.

Likenesses

photograph, 1867, repro. in Engen, Kate Greenaway · Elliott & Fry, photograph, 1870–79, NPG [see illus.] · watercolour, 1883 (after self-portrait by K. Greenaway), repro. in Engen, Kate Greenaway · photograph, c.1895, repro. in Engen, Kate Greenaway

Wealth at death

£6281 16s. 1d.: administration, 20 Dec 1901, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–16

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Rosemary Mitchell, ‘Greenaway, Catherine (1846–1901)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2005 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/33536, accessed 18 Oct 2017]

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Chester, England, 1846 - 1886, Saint Augustine, Florida

British, 1864 - 1912

Gateshead, England, 1850 - 1914, Herefordshire, England

Auchlunies, 1825 - 1916, Brighton

Brighton, 1867 - 1962, Kew