Edmund Evans

London, 1826 - 1905, Isle of Wight

Evans, Edmund (1826–1905), wood-engraver and printer, was born in Southwark, London, on 23 February 1826, the son of Henry Evans and his wife, Mary, and baptized on 9 April 1826 at St Mary Magdalen, Bermondsey. Following a brief education at a school in Jamaica Row kept by Bert Robson, an old sailor, in 1839, at the age of thirteen, he became ‘reading boy’ in Samuel Bentley's printing firm in Shoe Lane. When an overseer found that the boy had a talent for drawing, his parents apprenticed him in 1840 to Ebenezer Landells, a wood-engraver who had been a pupil of Thomas Bewick. As Evans wrote later in his Reminiscences: ‘I experienced great enjoyment in my beginning engraving; the work was quite to my liking, and the relief of getting to work at 9 o'clock, instead of 7, made me feel quite a young gentleman’ (Reminiscences, 8). The artist Myles Birket Foster, one year older than Evans, was also apprenticed to Landells, and a friendship grew up between the two young men which developed into a long collaboration; Foster later provided many of the designs which Evans engraved and printed.

When Evans's apprenticeship was completed in May 1847 he started business as a wood-engraver on his own account; he first took small premises in Wine Office Court, Fleet Street, but in 1851 moved to 4 Racquet Court (later expanded to include 116 and 119 Fleet Street). He was soon getting orders from publishers and employing assistants, including his younger brothers Wilfred and Herbert. Although he was a talented engraver in black and white, particularly of landscapes and flora and fauna, Evans made his name by exploiting a growing market for books with illustrations printed in colour. His first printing in colour was for Ida Pfeiffer's Visit to the Holy Land (1852), published by Ingram, Cooke & Co.: he engraved the blocks for three printings, in delicate shades of brown, pale blue, and pale yellow. There was, of course, nothing new about colour printing of this kind at that date: George Baxter's plates had been familiar for nearly twenty years, and colour printing from woodblocks in cheap children's books had been done by the firm of Gregory, Collins, and Reynolds between 1843 and 1849. Evans's undoubted achievement as a colour printer was as a popularizer rather than a pioneer. Although he was generally responsive to minor innovations and improvements—some of which he introduced himself—he was not responsible for the discovery or adoption of any major technological advances and his printing methods always remained based on the wood-engraving technique which dominated mid-century illustration. The new photomechanical methods of the 1890s were to pass the aged printer by.

The profitable basis of Evans's colour-printing business was established when Ingram Cooke asked him to start printing book covers in three colours for the new railway bookstall market. Speed, cheapness, and bright colours were the prime requisites, and Evans was particularly successful in mixing bright inks. He also introduced the use of yellow glazed paper, more serviceable than the previously used white. The yellow-backs, as they were known, were enormously popular. (Evans's own collection of more than 350 proofs of his yellow-back and other book covers passed, via Sir Michael Sadleir, into the Constance Meade collection, now in the Bodleian Library in Oxford.) Evans then turned almost entirely to colour engraving and printing: a popular employer (although an overtrusting businessman), he may have employed as many as thirty engravers during the 1860s and 1870s. His cheap three- or two-colour printing for publishers was sometimes astonishingly poor, but it is his higher quality work that won him his reputation. Sabbath Bells Chimed by the Poets (1856) was his first book with illustrations engraved and printed by him in full colours, after drawings by Birket Foster: with hand-coloured initials, it is a very pretty book indeed. Devised by Joseph Cundall, it was printed by the Chiswick Press, and the illustrations were presumably overprinted on the Chiswick Press sheets, in four or five colours, by Evans. Later editions of the book, in 1861, 1862, and after, were reset and entirely printed by Evans.

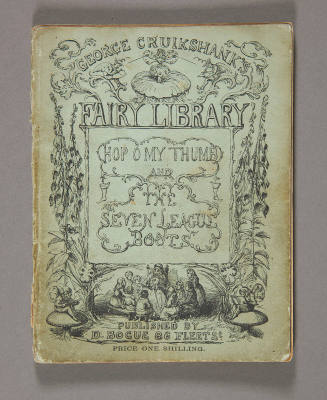

In the 1860s Evans established himself as the leading and the best woodblock colour printer in London. In 1860 Routledge published M. E. Chevreul's The Laws of Contrast in Colour, an important text illustrated with seventeen plates printed by Evans in up to about ten colours, brilliant in colouring and exciting as compositions. In 1864 came the substantial A Chronicle of England, written and illustrated by James Doyle, the elder brother of Richard Doyle: the many small illustrations, set in the text, are as bright as if they had just been painted. Exhibiting Evans's colour printing at its very best, they rival anything that Baxter ever did. Even more splendid was the Longman edition of Richard Doyle's masterpiece In Fairyland (1870), which contained sixteen plates printed by Evans in from eight to twelve colours: it is one of the most entrancing children's books ever made.

The next big development in commercial colour printing in Britain came with the publication of the Toy Books, introduced by Routledge and Warne in the mid-1860s. These children's books consisted of six pages of text and six pages of colour, printed on one side only, bound in paper covers, measuring about 10½ by 9 inches. The first titles were printed by Evans, but soon they became so popular that most of the other colour printers in London were called in. Those printed by Evans and the Dalziel brothers were printed from woodblocks; Kronheim and G. C. Leighton printed mostly from wood or metal, sometimes combined with lithography. The demand for Toy Books became so great that—like other printers—Evans turned publisher, and commissioned the artists himself. He commissioned Walter Crane to illustrate the first of these de luxe books, The Baby's Opera (1877); Crane designed between forty and fifty Toy Books, all printed and many commissioned by Evans, between 1865 and 1886. In 1878 Evans followed up this shrewd and successful move by engaging Randolph Caldecott to provide two Christmas Toy Books, John Gilpin and The House that Jack Built: the illustrator went on to produce two such books every year, sixteen in all, of which many more than a million copies have been printed. They remain in print and are still popular.

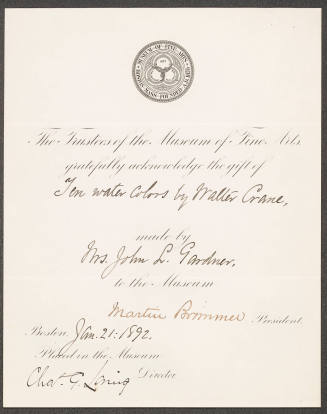

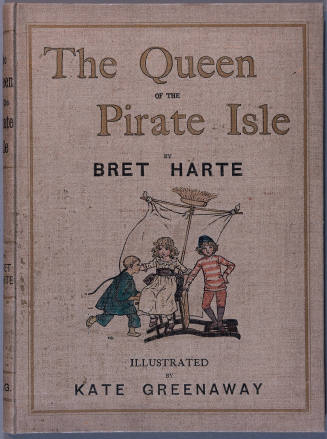

Evans's next protégé was Kate Greenaway: her first commission appears to have been for an Aunt Louisa's Toy Book from Kronheim & Co., Diamonds and Toads (1870), which is far more interesting than her later insipid work. In 1877 she took a book of her own verses and drawings to Evans, who immediately accepted them and obtained Routledge's agreement to publish them in a 6-shilling book to be called Under the Window. He printed 20,000 copies, which soon sold out, and he had great difficulty in keeping up with demand: Under the Window was still in print in 1972. Greenaway never allowed anyone other than Evans to engrave and print her illustrations, clearly recognizing how much Evans's interpretative skills and ability to match medium to style contributed to the final appearance of her work.

In 1864 Evans married Mary Spence Brown, a niece of Birket Foster, and they went to live in the village of Witley in Surrey; their neighbours included George Eliot and the Allinghams and their visitors Kate Greenaway and other artistic protégés. Evans retired from business in 1892—the success of his firm meant that he had left off engraving some years before—and settled in Ventnor in the Isle of Wight. He died there at his home, Belgrave View, Zig Zag Road, on 21 August 1905 and was buried in Ventnor cemetery. His business was carried on by his sons Wilfred and Herbert (he also had three daughters) and was amalgamated with another firm, W. P. Griffith Ltd, in 1953: in 1966 Evans's grandson Rex Evans was managing director.

In his old age Evans wrote his Reminiscences, which were published, with illustrations and a selective list of his colour printing, by the Clarendon Press, Oxford, in 1967. The original manuscript is not now known to exist. The copy used for publication in 1967 was a typescript of 102 numbered pages—uncorrected, with gaps, and clearly never read by Evans. Some of its deficiencies clearly derive from its original: it contains typing errors and numerous inconsistencies and mistakes, such as might be expected in the unchecked reminiscences of a seventy-year-old man. Nevertheless, it offers a unique insight into the nineteenth-century wood-engraving and colour-printing world. It was presented by Rex Evans to the Constance Meade collection, which includes many of Evans's books and proofs.

Ruari McLean

Sources The reminiscences of Edmund Evans, ed. R. McLean (1967) · British and Colonial Printer and Stationer (7 Sept 1905), 3 · R. K. Engen, Dictionary of Victorian wood engravers (1985) · R. McLean, Victorian book design and colour printing, rev. edn (1972) · Bodl. Oxf., Constance Meade collection · ‘Some notes on the history of printing in colour’, British and Colonial Printer and Stationer (31 March 1904), 229–31 · M. Hardie, English coloured books (1906) · DNB · d. cert. · IGI

Archives U. Cal., Los Angeles, MSS, drawings, sketches

Likenesses pencil, repro. in McLean, ed., Reminiscences · photograph, repro. in McLean, ed., Reminiscences

Wealth at death £11,098 18s. 1d.: resworn probate, 13 Oct 1905, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–15

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Ruari McLean, ‘Evans, Edmund (1826–1905)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/33035, accessed 27 Oct 2015]

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Chester, England, 1846 - 1886, Saint Augustine, Florida

British, 1864 - 1912

Preston, England, 1868 - 1936, London

Brighton, 1872 - 1898, Menton, France

Chilvers Coton, Warwickshire, 1819 - 1880, London

Geneva, 1826 - 1897, London