Image Not Available

for Robert Bridges

Robert Bridges

Walmer, England, 1844 - 1930, Oxford, England

Britain's poet laureate from 1913 to 1930. A doctor by training, he achieved literary fame only late in life. His poems reflect a deep Christian faith, and he is the author of many well-known hymns. Wikipedia accessed 10/5/2017

Bridges, Robert Seymour (1844–1930), poet, was born at Walmer, Kent, on 23 October 1844, the fourth son and eighth child of John Thomas Bridges (1805–1853) and Harriett Elizabeth Affleck (1807–1897), third daughter of the Revd Sir Robert Affleck of Dalham, Suffolk.

Ancestry and early years

The Bridges family had been yeoman farmers in the Isle of Thanet since the sixteenth century, but John Thomas Bridges, who inherited the property in the late 1820s, did not want to farm and moved his young family to Walmer, where in 1832 he purchased Roseland, a house with some 6 acres of land perched on a height from which it was possible to look down to the sea and Walmer Castle, one of the coastal forts built by Henry VIII and a residence of the duke of Wellington in his capacity as lord warden of the Cinque Ports. There were several military bases in the area and two of Robert's elder brothers were to enter the forces. Robert's early years were spent in a happy family with Puseyite religious belief, music, and games in the large garden or on the rolling countryside around Upper Walmer or its pebbly beach. The importance of these formative experiences is celebrated in poems such as ‘The Summer-House on the Mound’ and Bridges' memoir of Digby Mackworth Dolben, both of which show his ability to evoke a range of sensory impressions, remembered with astounding precision. It is this capacity to create vivid lines and images that is Bridges' main strength as a poet.

In 1853 Robert faced the first of many tragedies in his life. After a short illness his beloved father died at the early age of forty-seven. The following year his mother married the eminent churchman John Edward Nassau Molesworth (1790–1877), vicar of Rochdale in Lancashire, sold the family property, and moved her family to Rochdale. Robert was sent to Eton College, a school which his eldest brother, John Affleck Bridges (1832–1924), had attended. He was a good but not top student and his love of music, games, and mild pranks meant that he fitted in easily. He began lifelong friendships with Lionel Muirhead, who was a fine artist, the musician Hubert Parry, and V. S. S. Coles, who later became principal of Pusey House in Oxford. Fascinated by language, Bridges wrote poems, exchanging criticism with his ‘cousin’ Digby Mackworth Dolben until, comparing his efforts with those of the great literary figures, he despaired and wrote very little for a number of years. In 1860 his brother George (b. 1836) died; he had been a lieutenant aboard the royal yacht and had married the novelist Samuel Butler's sister Harriet in 1859.

Bridges' years at Corpus Christi College, Oxford (1863–7), were a continuation of his classical education, with leisure time given to music and sport where he was a distinguished oarsman. Among the friends he made at Oxford were William Sanday (later Lady Margaret professor of divinity) and the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins. He belonged to the ascetic, high Anglican Brotherhood of the Holy Trinity. But Oxford was entering a period of considerable change and his religious certainty was undermined by Darwinian debate and German higher criticism. The role religion was to play in his adult life was also altered in 1866 by the death of his younger brother, Edward (b. 1846), who had always had delicate health but with whom Robert had been hoping to live an informally religious life in which he would look after him. The drowning in July 1867 of Dolben, who was very devout, broke another of the religious ties of his youth.

Medical studies and practice

On leaving Oxford, from which he graduated with a second class in literae humaniores, Bridges travelled in the Middle East, partly to test his religious beliefs. He was away from January to June 1868 and returned to find that his elder sister, Harriett Plow (1837–1869), was dying after a murderous attack in which her husband and new-born baby had been killed. Bridges, who like his elder brothers was expected to choose a career, decided on medicine. He spent eight months in Germany learning German, the language of many scientific papers at the time, and then in 1869 registered as a student at St Bartholomew's Hospital, London. The explosion in scientific knowledge of the time was transforming medical training and making it more structured and rigorous. (Bridges later described it as the age of the microscope.) He balanced his heavy medical load with leisure spent with artistic friends, among whom at this period were Samuel Butler, the publication of whose Erewhon (1872) he offered to help finance; Harry Ellis Wooldridge, later Slade professor of fine art; John Stainer, who became university professor of music at Oxford; and Robert Bateman, a painter on the fringes of the Pre-Raphaelite group. Bridges joined the Savile Club in 1872, getting to know Edmund Gosse, Philip Rathbone, and the architect Alfred Waterhouse (1830–1905). In 1873 he published his first volume of poems, which gives hints of the crises through which he had been passing in lyrics such as ‘In my most serious thoughts o' wakeful nights’ and ‘In that dark time’. Most of the poems were written in 1872–3. It was a review of this volume by Andrew Lang that first made Hopkins aware that Bridges wrote verse.

Bridges failed his final medical examinations in 1873 and, unable to retake the papers immediately, spent six months in Italy with Muirhead, Wooldridge, and the Rathbones, who were collectors of art. He learned Italian and as much about Italian art as he could. He then spent July 1874 studying medicine in Dublin. Re-examined in December of that year, he obtained his MB and became a house physician to Dr Patrick Black at St Bartholomew's Hospital. In 1876 he published The Growth of Love: a Poem in Twenty-Four Sonnets, the oblique account of a love affair. The identity of the woman is unknown and he later expanded the volume, adding to its range of subjects and, unfortunately, altering its verb forms and pronouns away from current English. Early in 1876 he spent two extremely busy months working in the Hôpital de la Pitié in Paris. He saw as much French theatre as he could squeeze into his schedule, an experience which heavily influenced the plays he later wrote. It was a year in which he was elected a member of the Royal College of Physicians but also grieved over the illness and death of his youngest sister, Julia (b. 1841), who was a Sister of Mercy and who died from tuberculosis.

Bridges' next medical appointment was as a casualty physician at Bart's, an account of which he published in 1878. The physicians were placed under immense pressure, expected each morning to diagnose the ailments of 150 patients in under two hours. Bridges was exceptionally conscientious, spending significantly more time on each case. In the year he saw nearly 31,000 patients in the casualty ward. In 1878, in addition, he became out-patients' physician at the Hospital for Sick Children, Great Ormond Street, and assistant physician at the Royal Northern Hospital, Islington, giving some 50,000 consultations. The publication of his report on the casualty department of Bart's, in which he was critical of its organization for physicians and patients, probably explains his not being offered any further appointments there. He transferred his efforts to the other two hospitals, becoming full physician responsible for the training of some of the medical students at the Royal Northern. Edward Thompson, a friend in Bridges' last years, later remarked that he had never known anyone as sensitive as Bridges to others' physical suffering (Thompson, 7). Bridges also published in 1879 and 1880 two volumes of poetry which contain some of his finest lyrics, including his experiments in sprung rhythm in ‘London Snow’, ‘The Voice of Nature’, and ‘On a Dead Child’.

In June 1881 Bridges developed pneumonia. He took more than a year to recover and, looked after by Muirhead, spent much of the winter in southern Italy. The long recuperation gave him time to rethink his priorities. The deaths of so many of his siblings meant that he now had a greater share of the family wealth. When his mother, to whom he was devoted, had been widowed again in 1877, he had made a home for her with him in London, and their combined income meant that he no longer needed to earn a salary. In addition, as he later recorded, he had a poor memory and was badly worried by the strain on it at a time when doctors were not yet allowed to specialize and were even expected to remember the recipes for the drugs they prescribed. Since the volumes of poetry he had published had met with an encouraging response, he resolved to give up medicine and spend his time writing.

First writings, marriage, and literary friendships

In August 1882 Bridges and his mother moved to a manor house in the village of Yattendon, near Newbury, Berkshire. The next two decades were ones of great productivity. He wrote eight plays, a masque (Prometheus the Firegiver), a translation of Apuleius's Eros and Psyche, a revolutionary study of Milton's prosody, and more volumes of lyric poems. He collaborated with various musicians, including Hubert Parry and Charles Villiers Stanford, and, with Harry Ellis Wooldridge, produced The Small Hymn-Book: the Word-Book of the Yattendon Hymnal (1899), which was important in the reform of English hymnody and the resuscitation of Elizabethan music.

These were also years of great personal happiness. On 3 September 1884 Bridges married (Mary) Monica Waterhouse (1863–1949), the architect's elder daughter, who was some twenty years his junior [see below]. The couple had three children: Elizabeth (1887–1977), Margaret (1889–1926), and Edward Ettingdene Bridges, first Baron Bridges (1892–1969), secretary to the cabinet. It was to be an exceptionally successful partnership with shared interests, most especially in music and calligraphy. In 1903 Monica and Margaret contracted tuberculosis and for some years the family spent periods living near sanatoriums where the mother and daughter were institutionalized, as well as nine months in Switzerland in 1905–6. In 1907, with money left them by Alfred Waterhouse, the Bridgeses built Chilswell on Boars Hill, near Oxford.

Through Monica, Bridges came to know her cousin Roger Fry, who was the first of several prominent members of a younger generation with whom Bridges was to become acquainted. They included W. B. Yeats, Ezra Pound, Henry Newbolt, Mary Coleridge, Robert Graves, Virginia Woolf, and E. M. Forster, though, despite Bridges' friendliness, only Newbolt and Mary Coleridge seem to have been at ease with him and few publicly acknowledged his assistance or their admiration for his poetry. The friendship with another young man, W. J. Stone, the son of a former master at Eton, prompted Bridges to try writing English verse using classical quantitative metres. He translated parts of the Aeneid and wrote two long discursive epistles and a number of lyrics. The first of the epistles, ‘Wintry Delights’, and the lyric ‘Johannes Milton, senex’ are attractive examples of the method.

In 1909 Bridges published the first of several editions with memoirs of friends. This was Poems by the Late Rev. Dr. Richard Watson Dixon, whose friendship he had made through Hopkins. The second was The Poems of Digby Mackworth Dolben (1911). When he turned for a second time to The Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins (1918)—his first attempt having been shortly after Hopkins's death in 1889—Bridges unfortunately found that his feelings were too complex for a biographical memoir and he wrote instead a critical introduction and, most unusually for a contemporary poet at the time, explanatory notes to the poems. He later composed a memoir to accompany The Collected Papers of Henry Bradley (1928) and an introduction to A Selection from the Letters of Sir Walter Raleigh, 1880–1922 (1928). The memoirs were subsequently republished as Three Friends and are masterpieces of their kind: vivid, informative, and beautifully written. His other prose works included Collected Essays (10 vols., 1927–36) on a range of topics from the writing of poetry, Shakespeare, the relation of words and music, and an important study of John Keats, to shorter pieces which had been published from 1919 to 1930 in the Tracts of the Society of Pure English, an organization of which he was a founder member. These included one on English pronunciation for early use by the BBC.

The poet laureateship and The Testament of Beauty

In 1912 Oxford University Press published Bridges' Poetical Works, Excluding the Eight Dramas in the Oxford Standard Poets series. He was one of only two living poets to be included in the series, and the honour was based in part on the facts that his naturalistic handling of rhythm was influencing younger writers and that the demand for his Shorter Poems had necessitated their reprinting four times in five years. Poetical Works sold 27,000 copies in its first year alone, a popularity that led to Bridges' being offered the poet laureateship a year later when Rudyard Kipling refused it. Had he known the sort of poem ‘written to order’ the post would entail in the First World War, he might not have accepted (and might well not have been asked). His main poetic interest in 1913 was in developing a prosody appropriate to modern subjects that was independent of traditional rhythm and rhyme but, unlike free verse, was able to play off poetic units against syntactic ones. His experiments centred on syllabics, which he developed simultaneously with and independently of the American poet Marianne Moore. The strengths and variety of which the metre is capable can be seen in New Verse (1925) and The Testament of Beauty (1929).

Bridges' contribution to the war effort included belonging to ‘Godley's army’, a regiment of Oxford citizens past military age. The better war poems he wrote can be found in ‘October’ and other Poems and New Verse. He also compiled The Spirit of Man, a very popular anthology of poetry and prose extracts for soldiers and civilians. His son Edward was posted to the western front in the autumn of 1915 and, shortly after the Bridges' home was gutted by fire, was repatriated wounded in February 1917. Fearful of the long-term effect of what he saw as the vengeful nature of the treaty of Versailles, Bridges was a vocal advocate of the League of Nations. His political role gave him more contact with Americans than he had had previously and in 1924 he accepted an invitation from the University of Michigan to spend three months there talking to groups of students, including delivering a fascinating lecture to the medical school on his own medical experience.

In 1926 Bridges' daughter Margaret died, and he and his wife were devastated. Urged by Monica, he tinkered with a poem he had begun two years earlier. Then, after a break, he returned to it and spent the next three years writing what became The Testament of Beauty, the longest of his poems. It is a discursive work, setting out his understanding of man's nature, spiced with scenes and incidents from his experience and reading. When Oxford University Press published it, just in time for Bridges' eighty-fifth birthday in 1929, they were unprepared for its success. Printings could scarcely keep up with demand, and by 1946 it had sold over 70,000 copies. On 3 June 1929 Bridges was awarded the Order of Merit, which was the last of a list of distinctions that included an honorary fellowship of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, an honorary DLitt from Oxford University, honorary LLDs from St Andrews, Harvard, and Michigan universities, a fellowship of the Royal College of Physicians, and an honorary fellowship of the Royal Society of Medicine.

Bridges' health was failing, undermined by cancer and its complications. He died at his home, Chilswell, on 21 April 1930 and was buried at Yattendon. The poet Henry Newbolt, who wrote the obituary for The Times (22 April), spoke of his

great stature and fine proportions, a leonine head, deep eyes, expressive lips, and a full-toned voice, made more effective by a slight hesitation in his speech. His extraordinary personal charm was, however, due to something deeper than these; it lay in the transparent sincerity with which every word and motion expressed the whole of his character, its greatness and its scarcely less memorable littlenesses. His childlike delight in his own powers and personal advantages, his boyish love of brusque personal encounters, his naïve pleasure in the beauty of his own guests and the intellectual eminence of his own friends and relations—none would have wished these away. ... Behind them was always visible the strength of a towering and many-sided nature, at once aristocratic and unconventional, virile and affectionate, fearlessly inquiring and profoundly religious.

(Mary) Monica Bridges [née Waterhouse] (1863–1949) was born at Barcombe Cottage, Victoria Park, Manchester, on 31 August 1863. Her early years were spent at the beautiful estate of Fox Hill, near Reading. The Waterhouses were devout and musical and Monica became a competent pianist and composer. Her mother Elizabeth, née Hodgkin (1834–1918), was a Quaker but joined the Church of England a few years after her marriage. She taught the children painting and handicrafts and encouraged them to share her love of poetry.

In 1878 Alfred Waterhouse bought the Yattendon estate near Newbury and built there a home for his family into which they moved in April 1881. The Waterhouses were the local squires of the village of Yattendon, building a well, equipping a reading-room and lending library, and running evening classes. In the late 1870s, when Monica first met Robert Bridges, she was no more than fifteen or sixteen.

Despite suffering a number of serious illnesses, Monica was Bridges' partner in many of his artistic projects. These ranged from music to modifications of spelling with a set of phonetic founts based on Anglo-Saxon letters, and development of typeface, especially the Fell types of the early sixteenth century which the Bridges brought back into press use by choosing them for the Yattendon Hymnal (1895–9). She helped Harry Ellis Wooldridge to provide Palestrinal harmonization for nearly eighty plainsong melodies used in the hymnal. She also became an expert calligrapher, publishing A New Handwriting for Teachers (1899), which was influential in establishing an italic hand in schools, and helping with a tract on handwriting (S. P. E. Tract XXIII). Bridges placed great trust in her literary judgement, not letting his work out of his hands until she had seen it. She transcribed the pages of The Testament of Beauty as he wrote it between 1924 and 1929 and Bridges instructed the Oxford University Press to rely on her judgement should he die before it were published. In 1927 Monica began to edit small volumes of Bridges' collected essays, partly as an experiment in his extended alphabet. After his death she guided the series to completion in 1936.

From its inception in 1919, Monica participated in meetings of the committee of the Society for Pure English, for which Bridges had written a number of his essays. She collaborated with him on some tracts under the shared pseudonym Matthew Barnes, did much of the secretarial work in the early 1920s, and on Bridges' death became a full member of the committee. Logan Pearsall Smith paid tribute to her ‘enthusiastic interest’ and ‘clear and fine judgement’. Monica remained at Chilswell until 1943, when a bomb damaged it, and she then rented a room from a neighbour. By the time Chilswell could be repaired she was too frail to live there and moved to a rest home in south London run by the Misses Alexander. She died on 9 November 1949 and was buried with Robert Bridges at Yattendon. The family's monument there to Monica and her husband reads ‘In omnibus operibus eius adjutrix’.

Catherine Phillips

Sources

C. Phillips, Robert Bridges: a biography (1992) · The selected letters of Robert Bridges, ed. D. E. Stanford, 2 vols. (1983–4) · H. Newbolt, The Times (22 April 1930) · The Times (May 1930) · The Times (31 July 1930) · DNB · E. Thompson, Robert Bridges, 1844–1930 (1944) · d. certs. [Robert Seymour Bridges; Mary Monica Bridges] · L. P. Smith, ‘Robert Bridges and the S. P. E.’, S. P. E. Tract, 35 (1931), 481–502 · private information (2004) [Bridges family]

Archives

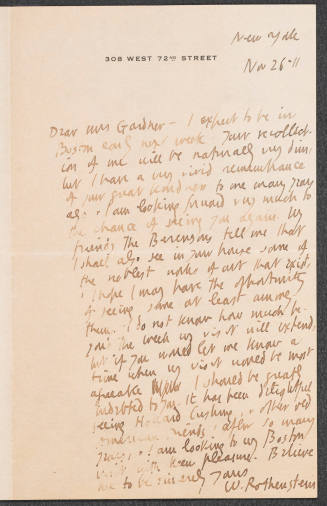

Bodl. Oxf., MSS, corresp., and literary letters, corresp., and MSS :: BL, corresp. with Samuel Butler, Sir Sidney Cockerell, Norman MacColl, E. W. Scripture, Charles Wood · BL, corresp. with George Bernard Shaw, Add. MS 50529 · BL, letters to G. K. Chesterton, Add. MS 73235 · Bodl. Oxf., corresp. with Henry Bradley; letters to A. H. Bullen; corresp. with Samuel Butler; letters to Bertram Dobell; letters to Alfred Fairbank; letters to H. A. L. Fisher; letters to Edmund Gosse; letters to J. W. MacKail; letters to Harold Minto; letters to Gilbert Murray; letters to Henry Newbolt; letters to Logan Pearsall Smith; letters to E. J. Thompson; corresp. with W. B. Yeats · Bodl. Oxf., letters to Lascelles Abercrombie; letters to A. C. Benson · CUL, letters to F. J. H. Jenkinson · Duke U., Perkins L., letters to Edmund Gosse · Harvard U., Houghton L., letters to Sir William Rothenstein · King's AC Cam., letters to E. M. Forster · King's AC Cam., letters to Roger Fry [incl. copies] · RCP Lond., letters to Sir Thomas Barlow; letters to Samuel Gee · Royal College of Music, London, letters to C. V. Stanford · Somerville College, Oxford, letters to Percy Withers · Trinity Cam., corresp. with R. C. Trevelyan · U. Reading L., letters to George Bell & Sons; letters to Sir Hubert Parry and Lord Arthur Ponsonby · Wellcome L., letters to Sir Thomas Barlow and Lady Barlow · Worcester College, Oxford, letters to C. H. O. Daniel

Likenesses

F. Hollyer, sepia photogravure, 1888, NPG [see illus.] · C. W. Furse, oils, 1893, Eton, Marken Library; repro. in D. E. Stanford, In the classic mode: the achievement of Robert Bridges (1978) · W. Rothenstein, lithograph, 1897, BM, NPG · W. Strang, etching, 1898, BM, NPG; repro. in Stanford, ed., Selected letters of Robert Bridges, vol. 1 · W. Strang, gold-point engraving, 1898, NPG · W. Richmond, oils, 1911 · Mrs M. G. Perkins, photogravure, 1913, NPG; repro. in Testament of beauty (1929) · W. Rothenstein, pencil drawing, 1916, Eton · T. Spicer-Simson, incised plasticine medallion, 1922, NPG · W. Stroud, two photographs, 1923, NPG · M. Beerbohm, caricature, 1924 (The old and young self), AM Oxf. · O. Morrell, photograph, 1924, repro. in D. E. Stanford, In the classic mode: the achievement of Robert Bridges (1978) · O. Morrell, photograph, 1924, NPG · A. L. Coburn, photogravure, NPG; repro. in Men of mark (1913) · W. Rothenstein, drawings, repro. in English portraits (1897) · W. Rothenstein, drawings, repro. in Twenty-four portraits (1920) · W. Rothenstein, drawings, repro. in The portrait drawings of W. Rothenstein, 1899–1925 (1926) · photograph, repro. in A. H. Miles, ed., The poets and poetry of the century, 8: Robert Bridges and contemporary poets (1893), frontispiece · photographs, priv. coll.; repro. in Phillips, Robert Bridges

Wealth at death

£6928 10s. 6d.: probate, 26 July 1930, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–16

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Catherine Phillips, ‘Bridges, Robert Seymour (1844–1930)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/32066, accessed 5 Oct 2017]

Robert Seymour Bridges (1844–1930): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32066

(Mary) Monica Bridges (1863–1949): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/75584

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Ledbury, England, 1878 - 1967, near Abingdon, England

Fockbury, England, 1859 - 1936, Cambridge, England

Weybridge, England, 1861 - 1923, Salisbury, England

Saxmundham, England, 1843 - 1926, Sissinghurst, England

Bradford, Yorkshire, 1872 - 1945, Far Oakridge

London, 1845 - 1927, Clonmel, Ireland

Calcutta India, 1776 - 1847, London