Image Not Available

for Mary Wortley Montagu

Mary Wortley Montagu

London, 1689 - 1762, London

LC Heading: Montagu, Mary Wortley, Lady, 1689-1762

Biography:

Montagu, Lady Mary Wortley [née Lady Mary Pierrepont] (bap. 1689, d. 1762), writer, was baptized at St Paul's, Covent Garden, London, on 26 May 1689. She was the eldest child of Evelyn Pierrepont, later first duke of Kingston (bap. 1667, d. 1726), and his first wife, Lady Mary Feilding (1668/9–1692). Her mother had three more children before dying late in 1692. The children were brought up by their Pierrepont grandmother until Mary was nine. (She was now Lady Mary, her father having succeeded his surviving brother as earl of Kingston in 1690.)

On her grandmother's death, Lady Mary passed to the care of her father. In the library of his mansion, Thoresby Hall in the Dukeries of Nottinghamshire, she set herself to ‘stealing’ her education, studying Latin when, she said, ‘everyone thought I was reading nothing but romances’ (Spence, Letters, 357; Spence, Observations, no. 743). At about fourteen she filled two albums with writings: poems, a brief epistolary novel, and a prose-and-verse romance modelled on Aphra Behn's Voyage to the Isle of Love (1684). She had a circle of literate female friends of her own age, and apparently corresponded with two bishops, Thomas Tenison and Gilbert Burnet, who supplemented the instruction of a governess whom she despised.

Marriage and embassy to Constantinople

In 1710 Lady Mary's friend Anne Wortley died, and Anne's brother Edward Wortley Montagu (1678–1761), who had already been dictating his sister's letters to Lady Mary, became her correspondent in his own person. He formally offered himself to her father as a suitor for her, but was rejected because of his conscientious objection to entailing his estate on his hypothetical future eldest son. To family estates at Wortley near Sheffield he and his father were fast adding great holdings of mines in both the Barnsley and the Durham coalfields. To him, over more than two years, Lady Mary addressed a remarkable series of courtship letters, constructing herself as a serious-minded and submissive potential wife to a demanding, even querulous, potential husband.

What provoked their eventual marriage was her father's pressure on Lady Mary to marry another candidate, Clotworthy Skeffington, heir to an Irish peerage. The father (by now marquess of Dorchester) was inflexible. Lady Mary had fallen in love with another, unidentified man, who seems to have been out of the question for marriage. She and Edward Wortley Montagu eloped and were married at Salisbury, apparently on 23 August 1712. (The date comes from an anniversary letter, written by her and annotated by him: he altered the date he first wrote.) For the rest of her life she felt beholden to the husband who had taken her without a portion.

The first two and a half years of Lady Mary's marriage were spent mostly in the country, latterly at Middlethorpe Hall near York. She bore her son (Edward Wortley Montagu the younger) on 16 May 1713, on one of her visits to London. Writings from these years include a poem of wifely submission beginning ‘While thirst of power’ (Essays and Poems, 179), a critique of Addison's Cato, an epilogue to the same play, and the only contribution to The Spectator to be written by a woman.

The accession of George I revolutionized the Wortley Montagus' fortunes. Lady Mary arrived in London at new year 1715 and plunged into both intellectual and court society. For a year she courted both George I and the prince of Wales, as well as striking up friendships with literati like Alexander Pope, John Gay, and the visiting Abbé Antonio Conti. Struck down by smallpox in December 1715, she surprised her circle by surviving. Disgrace at court followed, for during her illness someone circulated the satirical ‘court eclogues’ she had been writing. One of these was read as an attack on Princess Caroline (a reading which disregards the fact that the ‘attack’ is voiced by a character who is heavily satirized). Three of the six poems were illicitly printed by Edmund Curll, upon which Pope, professedly defending Lady Mary, conspired to dose Curll with an emetic, and wrote up and published a grisly account of the outcome.

Lady Mary left London in August 1716 to accompany her husband on his embassy to Constantinople, seat of the Ottoman empire. Owing to the transformation of European politics by the battle of Peterwardein shortly after they set out, and a requirement that Wortley Montagu pick up further instructions at both Hanover and Vienna, they travelled overland, criss-crossing Europe on the way. They reached Turkey in spring 1717, after a fearsome journey through wolf-infested forests and across the battlefield of Peterwardein (where bodies of men, horses, and camels still lay deep-frozen in the snow). Lady Mary sent home long letters describing her travels, and she kept copies for future reworking as a travel book. She laid a foundation of expertise in Turkish culture in three weeks billeted in Belgrade with an efendi, or Islamic scholar, with whom she had wide-ranging conversations on oriental languages, literature, religions, and social customs. She was delighted with the civility of women at a public bath building in Sofia, socially poised and graciously welcoming although stark naked.

Lady Mary's time in Turkey (divided between Adrianople, Constantinople, and Belgrade Village, a country retreat near the latter) turned out to be brief. Her husband, hoping to win great national and personal benefit by brokering a peace between the Ottoman and Austrian empires, found himself recalled, purely, it seems, because of a change of ministry at home. Very reluctantly, the Wortley Montagu family (with a new addition, a baby born on 19 January 1718: the future Mary Stuart, countess of Bute) sailed for home on 5 July 1718. Lady Mary was consoled for leaving Constantinople by the scholarly pleasures of a Mediterranean voyage. She and her husband disembarked at Genoa, crossed the Alps, and made a last stop in Paris, where she observed the peak period of John Law's Mississippi scheme.

1720s: Pope and smallpox

Back at home Lady Mary seems not to have taken up her court career with the same seriousness as before. Her husband acquired houses in Covent Garden and at the newly fashionable Twickenham. He sat in parliament and spent much of his time pursuing business in Yorkshire, whither Lady Mary did not accompany him. Instead she read, wrote, gardened, embroidered, and oversaw the education of her daughter. She edited her travel letters, but decided not to publish them. She wrote a series of outspoken poems on the topic of society's unjust treatment of women. Her friendship with Pope turned to bitter animosity, for reasons which are no better understood today than they have ever been. She formed new friendships: with Molly Skerrett, who became the mistress and eventually the second wife of Sir Robert Walpole, with Lady Stafford, a Frenchwoman settled in England, and with John, Lord Hervey, Walpole's right-hand man in the House of Lords. She included among her friends both Mary Astell and Sarah, duchess of Marlborough. She wrote funny, excoriating letters about the vagaries of fashionable people to amuse her next sister, Frances Erskine, countess of Mar, who was living in penury in Paris with her husband, leader of the first Jacobite rising.

Lady Mary's most important activity during the 1720s, for the world if not for herself, was the introduction to Western medicine of inoculation against smallpox. She had lost her only brother to this dread disease as well as nearly dying of it herself. In Turkey she had discovered that inoculation (with live smallpox virus) was a common procedure in folk medicine, administered to all comers by an old woman who made it her business. Lady Mary and Charles Maitland, the Aberdeen-educated surgeon at the embassy, looked carefully into the local practice, and then with Maitland's help and support she had her nearly five-year-old son inoculated.

Lady Mary was not the first Western European to have a child inoculated while resident in Turkey. But she was the first to bring the practice home. In spring 1721, with an epidemic raging in England, she persuaded a reluctant Maitland to inoculate her small daughter. Maitland, with his career to protect, stipulated the attendance of medical witnesses. One of these, James Keith, had lost several children to smallpox already, and had a little son whom he immediately had inoculated. The practice of inoculating children spread rapidly among those who knew Lady Mary and who had already been bereaved by the disease. Lady Mary made herself available for proselytizing: she visited sickbeds and supported anxious parents, using her own daughter's immunity as a teaching aid. She interested Caroline, princess of Wales, in the procedure; Caroline arranged the famous experiment on prisoners in Newgate gaol. Hard-hitting and frequently slanderous media warfare broke out, abusing and defending the procedure in newspapers and pamphlets, and even from the pulpit. Lady Mary contributed a single, pseudonymous essay to this vituperative controversy. The whole affair made her well enough known for the common people to be ‘taught to hoot at her as an unnatural mother’ who had gambled with her children's lives (Essays and Poems, 35–6). She carried on at least one correspondence (now lost) with a country apothecary on the topic of inoculation.

The year 1728 marked a nadir in Lady Mary's life. Lady Mar (by now her only surviving sibling) succumbed to some form of madness under the strain of her husband's debts and his career as a political turncoat. Lord Mar's brother, Lord Grange (who is known for subsequently immuring his wife on the uninhabited island of St Kilda), wanted to get custody of her to ensure that her pension from the crown would remain with the Erskine family, as the only, inadequate substitute for Mar's confiscated estates. Lady Mary fought Grange in court and had the better of the fight. When he mustered a posse of friends to escort Lady Mar from London to Scotland, Lady Mary secured a warrant and pursued them on horseback, intercepting them at Barnet to bring her sister back.

Pope attacked Lady Mary in his Dunciad that same year: not his first printed attack, but the one which, appearing in a major poetic statement, set the scene for a decade in which almost no important publication of his failed to toss out some damaging allegation against her. Typically, his allegations are false in the main, but fantastically encrusted around some tiny grain of truth. She attempted in vain to silence him by enlisting the aid of shared friends, and wrote a number of ripostes which she did not publish (some of them in collaboration with her cousin the young Henry Fielding, whose patron she was). Among the flood of printed attacks on Pope it is possible that some by her still lie unidentified; but only one is known as almost certainly hers: Verses Address'd to the Imitator of Horace, attributed (on good grounds though without incontrovertible evidence) to her and Lord Hervey as joint authors. This was very probably put into a publisher's hands by Pope himself, who may well have judged that its appearance in print would mitigate the damage that its manuscript circulation was doing him.

1730s: family troubles and love

Information about Lady Mary's life is far sparser for the 1730s than for the 1720s. The younger generation gave trouble. Her son, who had already run away from Westminster School several times, was entrusted to the care of a tutor who had orders to keep him abroad. When he turned twenty-one he came home without permission, and had (in his father's absence) several public, acrimonious rows with his mother. Her niece Lady Frances Pierrepont (daughter of her late brother) eloped from her care, through her daughter's connivance, with a man whom Lady Mary regarded as a gold-digger. Next her daughter reached marriageable age, and Lady Mary found her husband had ambitious plans to secure a wealthy son-in-law. It fell to Lady Mary to give a polite brush-off to one suitor (Lord Egmont's heir), and preserve some surface of civility towards the successful candidate, Lord Bute, who was her daughter's choice but not her husband's. Wortley Montagu followed family tradition and withheld the dowry his daughter had been led to expect. During the courtship, it seems, Lady Mary wrote a play, ‘Simplicity’, an adaptation of Le jeu d'amour et du hasard by Marivaux, which depicts a heroine permitted, even encouraged, by her father to test her suitor under his benevolent supervision.

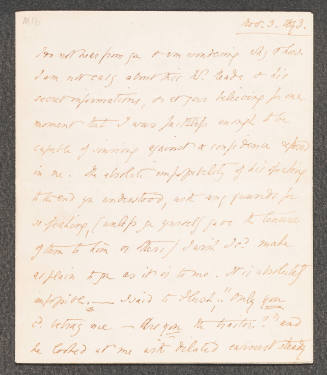

In 1736, the year of her daughter's wedding, Lady Mary fell in love. The object of her affection was Francesco Algarotti, Count Algarotti (1712–1764), a brilliant young middle-class Venetian who later became a respected critic of literature and the arts. He came to England fresh from impressing Voltaire and Mme du Châtelet, and was immediately elected to membership in the Royal Society and the Society of Antiquaries. Lady Mary wrote him love letters which are eloquent, hyperbolic, and frequently in French (the language both of love and of Enlightenment learning). She also wrote him poems. Her friend Lord Hervey was almost as badly smitten with him as she was, and Hervey's letters as well as hers pursued Algarotti when he left England.

Algarotti was slow to return, writing of his intention to come but not carrying it out. It appeared that Lady Mary's life went on as before, or that its most important new direction was her writing and (anonymously) publishing a pro-Robert Walpole periodical entitled the Nonsense of Common-Sense, which ran for nine issues in 1737–8. In its witty and resourceful essays, she challenges lords Chesterfield and Lyttelton (the moving spirits behind the anti-government journal Common Sense) and addresses some topics seldom met with in women's writing, such as industrial wages, interest rates, and censorship.

But at this time her life was bitter to Lady Mary. Her daughter was married and living in Scotland; her son was apparently written off; she had handed over custody of her sister to the sister's now adult daughter. Pope's attacks continued. Molly Skerrett (now Lady Walpole) died in June 1738, Lady Stafford in May 1739. While Lady Stafford lay ill, Algarotti appeared on another brief visit to England. Lady Mary, who had already proposed joining him in Italy, now began seriously planning to do so.

Lady Mary managed her departure with elaborate deceit: nobody but Hervey knew of either her motivation or her intentions. The story told to her husband and others was that she was travelling for her health, and would probably winter somewhere in the south of France. Recurrent rumours that her husband had banished her (according to the painter Joseph Farington, for losing money in financial speculation) are unsubstantiated. Lady Mary wrote to a new correspondent, Henrietta Louisa Fermor, countess of Pomfret, of her eagerness to join her abroad. She packed up her possessions, to be stored for the moment and later, perhaps, to follow her, and had a catalogue made of her library (an informative document which, however, lumps together as ‘pamphlets’ 137 titles which probably included her annotated copies of Pope's individually published poems).

Once she was abroad, Lady Mary's health and spirits improved. She travelled directly to Venice (while hinting to her husband at several episodes of indecision). There she rented a house, explored the city, picked up a number of old friendships (particularly with the savants Antonio Conti and Pietro Grimani, procurator of St Mark, whom she had met at Vienna), and made some enduring new ones (notably with Chiara Bragadin Michiel). She was warmly welcomed into Venetian society, and began holding a weekly salon. Venice pleased her both socially, as a place of freedom, and politically, as an aristocratic republic. All the while, however, she was waiting for Algarotti (who had travelled to Russia) either to join her or to name some other rendezvous.

Next year Lady Mary was on the move. She went from Venice to Florence, where she stayed two months with the Pomfrets. While there she met Horace Walpole (whom she erroneously believed to be full of friendliness and respect). From there she went on to Rome (for sightseeing), to Naples (where she failed to secure admittance to the recently opened ruins of Herculaneum), and back to Rome. On her second spell there her salon was much frequented by British grand tourists. Joseph Spence (tutor to Lord Lincoln, and future professor of poetry at Oxford) interviewed her for his collection of literary anecdotes and transcribed a number of her poems, which were published in 1747–8. She then travelled to Leghorn to receive her baggage, and thence to Turin, where Algarotti was currently an envoy from the court of Berlin, trying to enlist the kingdom of Savoy and Sardinia as an ally of Frederick the Great in the War of the Austrian Succession. (It was Frederick's summons, on his father's death, which had put paid to any intention Algarotti might have entertained of a life with Lady Mary.) During three months of spring 1741, these two odd lovers came to the end of their probably unconsummated affair.

Lady Mary spent that summer at Genoa, where she intervened on behalf of the republic in an international incident which involved a British breach of Genoese law. In the end a British court concurred with her in taking the Genoese side.

1742–1756: Avignon and Brescia

For two years Lady Mary's erratic movements had been dictated by her expectations of Algarotti. They were now dictated by the progress of European war. Italy expected invasion, so she crossed the Alps again, tried Geneva (which she disliked), and wintered at Chambéry. In 1742 she settled at Avignon, where she stayed for four ill-documented years. She did not particularly like the place, but because it was under the dominion of the pope it was safe from attack. By the time of the second Jacobite rising she was finding its population of exiled Scots and Irish dissidents an intolerable irritation, but she did not know how to get away.

In Avignon, Lady Mary mapped out the solitary life she led for the next decade or more. Her gift for languages enabled her to mingle in continental society more than most visiting English, but she preferred to be often alone. The town council made her a grant of a tower in the citadel (now destroyed) and here she lodged some of her books and constructed a belvedere. She made forays away from Avignon: to Orange in 1742 to meet her errant son and write an assessment of him for her husband; and to Nîmes in 1743, for a social function where she petitioned the governor of Languedoc (the duc de Richelieu) for clemency for persecuted Huguenots.

In 1746 Lady Mary made concerted attempts to get away from Avignon. She travelled around Languedoc seeking a place to settle; she discussed possible plans for travel. Finally she arranged with a native of the Venetian province of Brescia, Count Ugolino Palazzi, to escort her as far as Brescia, whence she planned to go on to Venice. She had to pay Palazzi's debts before they could leave; but still she judged the bargain worth while, since a few days later their path led right through the retreating Spanish and advancing Austrian armies. But after arriving at Brescia, at the house of Palazzi's mother, she fell gravely ill; and she got no further on her journey for ten whole years.

Brescia was a singularly lawless province, with a high murder rate. Ugolino Palazzi and his brothers were among the most notorious of its upper-class bandits, who lived largely by extortion backed with threats of violence. Lady Mary was not to know this. She rented a house from the Palazzis, in the Po valley town of Gottolengo. Because the house was dilapidated she improved and furnished it; since it lacked a garden she bought, through Palazzi's agency, a ‘dairy-house’ with gardens and vineyards, several miles off. When all her jewels were stolen during her first autumn in Gottolengo, she suspected Palazzi, yet she did nothing.

During these isolated years Lady Mary sent to her daughter her most personal, philosophical letters, expatiating on topics like the education of girls and the works of the modern novelists. She described her walks, her fishing, her gardening, her farming, and the social habits of her neighbours. She described also the beauties of Lovere on Lago d'Iseo, a holiday resort where she bought another palazzo and lived for months at a time. Many of her undated writings probably belong to these years, though she told Lady Bute that when she wrote the history of her own times she destroyed each section as she completed it. Her letters to her daughter and her husband make no mention of the harassment and anxiety which she later described in a document drawn up with the intention of suing Palazzi. Indeed, midway in her northern Italian sojourn, when a traveller who had attempted to visit her complained of violence from Palazzi, and the Venetian governor of the province enquired into her position, she maintained that she was perfectly at her ease and under no compulsion or restraint.

That was in 1750. From early 1754 she was trying to get away, but something always intervened. Either she fell ill (she had a dreadful bout with gum disease, but was saved by having her mouth cauterized), or her trusted woman-servant fell ill, or floods were up or bridges broken, or the roads were said to be infested with bandits. In spring 1756 she finally realized she was a prisoner. She made her escape with the aid of her secretary, Dr Bartolomeo Moro, and of one of Palazzi's aunts. She did not get off scot-free: all the title-deeds to property she had bought were stolen, and she was informed that in any case most of the sales had been legally invalid.

Final years

But Lady Mary reached her goal, and she shook off Palazzi. She bought a house in Venice and one in Padua, and spent a last few years among society as well as books. Many old friendships were restored (including that with Algarotti, with whom she exchanged letters of wit and philosophic speculation). She made new ones too, many of which are known only from the summaries of letters sent, which she kept at this time as she had done in Turkey. One correspondence which survives is that with Sir James Steuart, the political economist, and his wife, Lady Frances, who were exiled Jacobites. Lady Mary's brilliant, exuberant letters to Sir James suggest something of what must have been the quality of her lost letters to Pope, William Congreve, Hervey, Conti, Montesquieu, and other literary and Enlightenment figures.

Lady Mary's late years in Venice were marred only by a bitter feud with John Murray, the British resident, and Joseph Smith, the art collector, who was British consul there. The grounds for this quarrel seem to have been political, having to do with support for or opposition towards William Pitt; but the mode of it was to torment Lady Mary with insinuations that her learning was not respectable. This made her position harder when in 1761 news reached her of her husband's death, followed by the news that her son had contested the will, not in his own name but in hers.

The activities of Edward Wortley Montagu junior are much canvassed in surviving letters between his parents (who remained on the best of epistolary terms)—although a large batch of letters about him were later destroyed. Lady Mary encountered in many European cities the traces of his passage, in confidence tricks perpetrated and debts unpaid. She had come to believe that her husband ought to disinherit their son and leave his by now immense fortune to their daughter, Lady Bute, the mother of a large family. She had feared he might waver in his purpose to do this; now that he had done it, his will was challenged. This was the reason for her last journey, undertaken late in the season in 1761, when Europe was again at war, and she was suffering from advanced breast cancer.

En route from Venice to London, Lady Mary deposited the manuscript of her Embassy Letters with a protestant clergyman at Rotterdam, Benjamin Sowden, whom she apparently trusted to direct it into the hands of a publisher. (In fact he gave it up to Lord Bute, but not before it had been illicitly copied by two men, one of them the son of the publisher Thomas Becket.)

After arriving in London early in 1762, Lady Mary was a social sensation, like a revenant from another age. But she was not happy: if she had been well enough, she would have set off again for Venice. She evidently made yet more new friendships, since she left to Joshua Reynolds a ring engraved with both their names. She died at Great George Street, Mayfair, Westminster, on 21 August 1762, and was buried the next day in the vault of Grosvenor Chapel in South Audley Street.

Lady Mary was painted many times: by Charles Jervas as a shepherdess in 1710; by Sir Godfrey Kneller in 1715 (a painting which exists in almost innumerable versions or copies) and again in 1722 (a portrait done for Pope, in which she wears authentic Turkish dress brought back from her travels); by Jean-Baptiste Vanmour while she was in Turkey; by Jonathan Richardson once in unobtrusive travelling dress and once in dazzling gold with attendant black boy; and by Carlo Francesco Rusca among emblems including a skull. Another portrait ascribed to Kneller seems to show her in the identical costume to that she wears in Pope's picture, against a background encampment of Serbian tents. Costume and tents are strong circumstantial evidence that this is Lady Mary; but since another version of this picture (at Dulwich Art Gallery) bears the arms of her friend Dorothy (Walpole), Countess Townshend, the National Gallery (which owns a third version) does not accept it as Lady Mary.

Other pictures which claim to be of Lady Mary are too numerous to mention here. Turkish costume, which became widely popular, seems to have been regarded as sufficient grounds for attributions, of which some are feasible but many are not. The authenticated pictures have been often engraved. One particularly interesting engraving shows her portrait in an oval frame, along with matching portraits of the duke and duchess of Portland (son-in-law and daughter of her friend Henrietta Harley, countess of Oxford); the picture of Lady Mary is embellished with attributes to mark her talents and achievements: a trumpet and oak leaves for fame, a globe for travel, a caduceus for medicine, and a mahlstick for painting (or possibly for needlework design).

A number of Lady Mary's poems were printed in her lifetime, either without or with her permission or connivance: in newspapers, in miscellanies, and independently. Though she later told her daughter she had never published anything, this is demonstrably false, even if the only proven case of her active involvement is the Nonsense of Common-Sense. After Curll, Anthony Hammond included her in his New Miscellany of Original Poems, Translations and Imitations, by the most Eminent Hands (1720). It remains unknown whether she engineered the publication of Verses Address'd to the Imitator of Horace, The Reasons that Induced Dr Swift to Write a Poem call'd the ‘Lady's Dressing Room’, and the Answer to the Foregoing Elegy, the last of which is only probably hers. While she was abroad the London Magazine printed a number of her poems, one by one. Horace Walpole was responsible for her Six Town Eclogues, with some other Poems (1747), and in part responsible for Dodsley's inclusion of her the next year in his influential Collection of Poems.

Lady Mary's diary for the years since her marriage was long preserved by her daughter but was finally destroyed, as an act of filial piety. Meanwhile her Letters Written during her Travels appeared in three volumes from Becket and De Hondt (transcribed from the manuscript then held by Sowden) in the year after her death. An apparently pirated edition of her Letters (1764; said to be ‘Printed for A. Homer in the Strand, and P. Milton in St. Paul's Church-yard’) added some inauthentic material, which in 1767 was joined as a fourth volume to the Becket and De Hondt edition. Her Poetical Works (1768) collected pieces which had already appeared in print. In 1803 appeared her Works, edited by James Dallaway, published by Richard Phillips: a skimpy and deplorably edited selection from manuscripts in her family. Their appearance was a concession to Phillips, to prevent him from publishing other manuscripts not held by the family, which were then destroyed. During the nineteenth century two more editions repaired some but not all of Dallaway's inaccuracy. During the twentieth century Lady Mary's letters were edited separately from her essays, poems, and play, and from her longer fictions.

Montagu (like her literary predecessors Aphra Behn and Margaret Cavendish, duchess of Newcastle) had both the capacity and the serious ambition of a major writer. With these went inconsistent social responses, both conformist and resistant, to the path in life marked out by her rank and gender. She defied convention most memorably by her pioneering of inoculation, a course of action unparalleled in the annals of medical advance. Her letters and her poetry, which were admired by her contemporaries and successors, have more recently been overshadowed by her political periodical the Nonsense of Common-Sense (authorship unknown until the mid-twentieth century) and by her longer fiction (particularly the novella entitled in English Princess Docile; authorship unknown until near the end of the twentieth century). Scholarship has yet to catch up with the task of evaluating Montagu as author. But at the same time, the fascination of her life story—including its least visible parts: her quarrel with Pope, her relationship with the north Italian bandit Ugolino Palazzi—continues to upstage her writing in the public mind.

Isobel Grundy

Sources I. Grundy, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1999) · The complete letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, ed. R. Halsband, 3 vols. (1965–7) · Farington, Diary · J. Spence, Observations, anecdotes, and characters, of books and men, ed. J. M. Osborn, new edn, 2 vols. (1966) · J. Spence, Letters from the grand tour, ed. S. Klima (Montreal, 1975) · Lady Mary Wortley Montagu: essays, poems and ‘Simplicity: a comedy’, ed. R. Halsband and I. Grundy (1977); rev. edn (1993) · M. Wortley Montagu, Romance writings, ed. I. Grundy (1997) · M. Wortley Montagu, Selected letters, ed. I. Grundy (1996) · J. McLaverty, ‘“Of which being publick the Publick judge”: Pope and the publication of Verses address'd to the imitator of Horace’, Studies in bibliography (1998)

Archives Harrowby Manuscript Trust, Sandon Hall, Staffordshire, corresp., notes, literary MSS and MSS · Holborn Library, Camden, London, Local Studies and Archives Centre, letters written on travels in Europe, Asia, and Africa · Hunt. L. · JRL, papers · NL Scot., notes · priv. coll., letters :: Biblioteca Civica, Udine, Italy, Manin MSS · Bodl. Oxf., letters to Francesco Algarotti · Col. U., Halsband MSS · Lincs. Arch., letters to P. Massingberd · Lincs. Arch., Monson MSS · Lincs. Arch., Mundy MSS · NA Scot., Mar and Kellie MSS · Sheff. Arch., Wharncliffe MSS

Likenesses C. Jervas, portrait, 1710 · portrait, c.1712–1715 (after G. Kneller), Stratfield Saye, Hants. · G. Kneller, portrait, 1715 · J. -B. Vanmour, group portrait, oils, c.1717, NPG · G. Kneller, portrait, 1719–20, priv. coll. [see illus.] · G. Kneller, portrait, 1722 · C. F. Rusca, oils, c.1739, Gov. Art Coll. · G. Vertue, print, 1739, repro. in Wortley Montagu, Romance writings · C. Watson, stipple, 1803 (after G. Kneller), BM; repro. in The works of the Right Honourable Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, ed.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Kelloe, England, 1806 - 1861, Florence

Portsmouth, England, 1828 - 1909, Box Hill, England

Sussex, 1799 - 1870, Boulogne

Walmer, England, 1844 - 1930, Oxford, England

Kolkata, India, 1811 - 1863, London