William Makepeace Thackeray

Kolkata, India, 1811 - 1863, London

Biography:

Thackeray, William Makepeace (1811–1863), novelist, was born on 18 July 1811 at Calcutta, the only child of Richmond Thackeray (1781–1815), secretary to the board of revenue in the East India Company at Calcutta, and Anne Becher (1792–1864), second daughter of John Harman Becher, a writer for the East India Company, and his wife, Harriet.

Ancestry and early life

Harriet Becher, after the birth of Anne's younger sister (also Harriet), appears to have abandoned husband and children to elope with Captain Charles Christie under whose ‘protection’ she lived until his death in 1805. She then married Captain Edward William Butler of the Bengal artillery in October 1806, John Becher, her legal husband, having died in 1800. The novelist got to know his grandmother as Mrs Butler when he stayed with her in Paris in 1834–5, and when she lived with him in 1840–41 and again in 1847, the year she died. She is said to have been the model for Miss Crawley in Vanity Fair. Anne Becher was brought up by her paternal grandmother, also Anne Becher, whose severe evangelical beliefs did not preclude ambition for a marriage of wealth and position for Anne. When Anne fell in love with Henry Carmichael-Smyth (1780–1861), an ensign of the Bengal Engineers, her grandmother intervened, finally persuading Anne that the young man had died and sending the bereaved girl to India in April 1809 in the company of her sister Harriet, their mother, and Captain Butler. Anne was a beautiful woman and very successful in Calcutta social circles where Richmond Thackeray joined many others suitors, prevailing and marrying her on 13 October 1810. Her sister Harriet had married Captain Allan Graham eight months earlier.

The novelist's father, Richmond, second son of William and Amelia Thackeray, was born at South Mimms on 1 September 1781 and went to India at the age of sixteen to assume his duties as writer. By 1804 he had fathered a daughter by a native mistress, the mother and daughter being named in his will. Such liaisons being common among gentlemen of the East India Company, it formed no bar to his courting and marrying Anne Becher. The novelist's great-grandfather Thomas Thackeray (1693–1760), headmaster of Harrow School, chaplain to Frederick, prince of Wales, and, from 1753, archdeacon of Surrey, had sixteen children. Thomas's fourth son, also Thomas (1736–1806), was a surgeon at Cambridge, and one of his sons, William Makepeace (1770–1849), was a physician at Chester. The youngest son of Thomas the archdeacon, also named William Makepeace (1749–1813), married Amelia Richmond and fathered Richmond, the novelist's father. Amelia was third daughter of Colonel Richmond Webb, who was related to General John Richmond Webb, of Wijnendale fame, described in Henry Esmond. The novelist chose the Webb crest of arms as his own because it ‘was prettier and more ancient’ (Letters and Private Papers, 3.446); and he is said to have credited the Webbs with introducing ‘wits ... into the family’ which was otherwise a ‘simple, serious’ one (F. Bradley-Birt, ‘Sylhet’ Thackeray, 1911, 16).

Five months after William Makepeace Thackeray's birth, Richmond was promoted to the post of collector of the house tax at Calcutta and of the Twenty-four Pergunnahs, a district south of Calcutta. The family may have set up house at the collector's residence at Alipore, though Richmond's will refers to ‘the house in Chowringhee in which I reside’ (Ray, Uses of Adversity, 61). Some time in 1812 Richmond invited a new acquaintance home to dine: Captain Henry Carmichael-Smyth, Anne's supposedly deceased lover. He had been informed by Mrs Becher, who had returned all his letters, that Anne no longer cared for him. Mrs Fuller (the novelist's granddaughter) wrote, ‘After a while the situation became so impossible that Richmond Thackeray had to be told; he listened gravely, said little, but was never the same to Anne again’ (Letters and Private Papers, 1.cxiv; Ray, Uses of Adversity, 63). Thackeray's fiction is dotted with accounts of parental interference in young love.

Richmond Thackeray died on 13 September 1815 leaving an estate worth £17,000. His will directed annuities drawn from the estate of £450 to his wife, £100 each to his sister, Augusta, his son, William Makepeace, and his illegitimate daughter, Sarah, and about £30 in total to Sarah's mother and an old servant. Young William Makepeace was sent at the age of five to England in December 1816, while his mother Anne remained to marry Henry Carmichael-Smyth in the winter of 1817–18. The couple returned to England in 1819.

Thackeray was accompanied on his journey to England by a former colleague of his father, by his cousin Richmond Shakespeare, and by a native servant, Lawrence Barlow. When the ship stopped at St Helena, Barlow took Thackeray to see a man walking in a garden; ‘that is Bonaparte!’ said the servant. ‘He eats three sheep every day, and all the little children he can lay hands on!’ (Ray, Uses of Adversity, 66). William was taken in very briefly by his aunt Charlotte Sarah (Richmond's sister) and her husband, John Ritchie.

Early education

In the winter of 1817–18 Thackeray attended a school at Southampton

of which our deluded parents had heard a favourable report, but which was governed by a horrible little tyrant, who made our young lives so miserable that I remember kneeling by my little bed of a night, and saying, ‘Pray God, I may dream of my mother!’ (Ray, Uses of Adversity, 70)

In the following year he entered a school at Chiswick where he remained until December 1821, after which he was enrolled at Charterhouse School. Summers he spent with the Bechers at Fareham until the return of his mother and Major Carmichael-Smyth in 1819. Though he never returned to India, the India connections of the families that made up the Fareham circle are evident in many accounts of returned East India men, including Jos in Vanity Fair and Colonel Newcome in The Newcomes. Only one work, The Tremendous Adventures of Major Gahagan (1838), is set in India. Thackeray's treatment in the Chiswick school and at Charterhouse, which he attended from 1822 to 1828, may have been better than at the first school at Southampton, but his recollections of school tyrannies and the terrors of school boyhood show up repeatedly in his fiction. His portraits of Miss Tickletoby, Dr Birch, and Dr Swishtail and his descriptions of Slaughterhouse and Blackfriars schools suggest that flogging and fagging were the primary agents of instruction. His recollections were that he had been ‘licked into indolence’, ‘abused into sulkiness’, and ‘bullied into despair’ (ibid., 97). He must have felt keenly the difference between his treatment in England, even among his well-intentioned relatives, and what he had known in India where he was attended by numerous servants and played with by his mother and aunt. Among Thackeray's most convincing fictional portraits are those of young or misfit boys in school, like Dobbin in Vanity Fair, and of the loneliness of boys like Henry Esmond. However, the few surviving letters from Southampton and Chiswick, written under the censoring eyes of schoolmasters, do not betray the pain and misery portrayed in Thackeray's fiction.

Thackeray's academic achievements at Charterhouse were not outstanding, though his natural abilities caused him to rise through the ranks respectably (Ray, Uses of Adversity, 84–6). He was quite near-sighted and, having no spectacles, was unable to take a very active role in games—though, apparently for the amusement of older boys, he and a schoolmate, George Venables, were put to a fight in which the latter flattened the future novelist's nose (Letters and Private Papers, 2.256).

Thackeray spent the summers with his mother and Major Carmichael-Smyth at Addiscombe, near Croydon, until 1825, when they moved to a house named Larkbeare near Ottery St Mary and Exeter, the setting for much of Pendennis. The rector of nearby Clyst Hydon, the Revd Francis Huyshe, became a close family friend and was probably the model for Pendennis's would-be mentor, Dr Portman. In his final two years at Charterhouse Thackeray was a member of the first form and received ‘instruction’ directly from Dr Russell, who, Thackeray complained, refused to acknowledge any of his efforts or achievements and singled him out for put-downs. Thackeray's parodies of Russell began while in school and show up in much of his fiction. In the end Thackeray's formal education was weak, including little if any mathematics and involving a rote approach to classics that did little for the understanding. But Thackeray was a voracious reader and a keen observer of his surroundings. Perhaps the most ingrained notion Thackeray carried away from Charterhouse was a sense of class distinctions; for though the public schools mixed the sons of the very wealthy with those of lesser families, there was a keen sense of community that separated those at public schools from all others. There is more than a little truth in the notion that the Book of Snobs was ‘written by one of them’; for though Thackeray was able to see and depict pretension and overreaching English snobbism, he never ‘forgot his place’ or the codes learned in public school that separated him from less privileged men.

Thackeray's aunt Harriet Graham and her husband both died, leaving a daughter, Mary Graham, who from 1820 lived with the Carmichael-Smyths and as a younger sister to William. She played a Laura Bell to Thackeray's Pendennis and eventually married Colonel Charles Carmichael, the major's brother. Mary and her husband lent Thackeray £500 when hard times struck in 1841, a debt that hung as heavily over him as Pen's debt to Laura in Pendennis.

Years in Cambridge and Germany

Illness in his last year at Charterhouse, during which he reportedly grew to his full 6 feet 3 inches, postponed Thackeray's matriculation at Trinity College, Cambridge, until February 1829. Thackeray was ‘coached’ for college by the well-intentioned Major Carmichael-Smyth. It was appropriate to William Thackeray's paternal family background that he should try to think of himself as a potential scholar. The Thackeray side of the family was well known for its scholars, from the archdeacon, his great-grandfather, to his great-uncles and cousins the physicians, to his cousin Elias, a vicar, and two of his cousins, the provost and vice-provost of King's College, and his cousin by marriage, a professor of political economy. Though Thackeray entered late, he was determined, perhaps under some pressure from his mother's expectations, to read for an honours rather than a pass degree. Thackeray apparently saw little of his tutor, William Whewell, but his private tutor, Henry Fawcett, found Thackeray a ready enough scholar at first. Like Pendennis, he seems to have applied himself with some enthusiasm, studying from eight in the morning to three every day, but before long he decided that private reading would suit his ends better than assiduous attendance at lectures.

Cambridge distractions soon eroded study time and energy, but it was not all wine parties and debates and outings. Thackeray read widely: histories (Gibbon, Hume, Smollett), modern novels and poems—making a special effort with Shelley, whose Revolt of Islam impressed him. And he began to write. He had published a couple of poems and a translation the year before in the Western Luminary, a Devon newspaper, but at Cambridge his contributions to The Snob and, after the long vacation, to its replacement, The Gownsman, began to develop his talents in parody and humour. Having arrived in late February, his first contribution to The Snob was his famous ‘Timbuctoo’, a parody (not submitted, of course) of the prize competition, which Tennyson won that year. By mid-May he was working closely with The Snob's editor, William Williams, contributing six more pieces by the end of term in June.

Thackeray's relatives in Cambridge welcomed him with open arms, but he found their company staid. When he applied to his cousin the vice-provost for advice about his progress toward the end of his first term, it was suggested he hold over and not take the first-year examinations. In the end he did take them—five days of eight-hour exams on mathematics and classical authors. He had been sick before the exams and yet made it to the top of the fourth class ‘where clever “non-reading” men were put, as in a limbo’ (Letters and Private Papers, 1.76).

In the company of William Williams, just graduated and serving supposedly as Thackeray's mathematics coach for the summer, Thackeray went to Paris to learn French and extend his education with continental experience. Williams soon abandoned Thackeray, who discovered for himself museums, artists' studios, and Frascati's gambling opportunities. By the account he sent home, the first visit to Frascati's was a brush with evil that taught him the lesson to avoid gambling, whereas in truth it seems to have whetted his taste for play, which by the end of his second year at Cambridge landed him some £1500 in debt. Thackeray returned to Cambridge in October, where distractions continued to outweigh the honours curriculum in maths and classics. It is not known exactly when Thackeray decided that further pursuit of an honours degree was a waste of time, but the decision formed a part of his break for independence from his mother, to whom he wrote the next year:

You seem to take it so much to heart, that I gave up trying for Academical honours—perhaps Mother I was too young to form opinions but I did form them—& these told me that there was little use in studying what could after a certain point be of no earthly use to me ... that three years of industrious waste of time might obtain for me mediocre honours wh. I did not value at a straw[. I]s it because I have unfortunately fallen into this state of thinking that you are so dissatisfied with me[?] (Letters and Private Papers, 1.138)

Only four contributions to The Snob's successor The Gownsman and two letters home offer evidence of Thackeray's second-year activities at Cambridge. But his circle of acquaintance included important friendships with Henry Alford, John Allen, Henry Nicholson Burrows, Charles Christie, William Hepworth Thompson, and John Hailstone—all members of a debating society formed in imitation of the Apostles (Ray, Uses of Adversity, 128). His other friends included James Spedding, John Mitchell Kemble, A. W. Kinglake, William Brookfield, Richard Monckton Milnes, and Alfred Tennyson. His best friends in the autumn term were John Allen, who influenced him to affirm his religious beliefs, and Edward Fitzgerald, a shy man who shared Thackeray's love of literature and who influenced him to doubt his beliefs. Fitzgerald graduated in December, leaving the field to Allen, who lost out to faster men, including Harry Matthews, the prototype of Bloundel in Pendennis, who seems to have led Thackeray into gambling dissipation in the Lent and Easter terms.

At the examinations that year Thackeray ended in the second class, dashing any hopes of an honours degree. At the Easter break he announced he would spend the vacation with a friend named Slingsby in Huntingdonshire, but instead went to Paris with Edward Fitzgerald, an outing about which, he years later remarked, ‘my benighted parents never knew anything’ (Ray, Uses of Adversity, 126). There is some evidence to believe that Thackeray contracted a venereal disease at this time. In October 1859 he wrote in a familiar strain, ‘My old enemy gives me rather serious cause for disquiet—not the spasms—the hydraulics—a constant accompaniment of those disorders is disordered spirits’ (Letters and Private Papers, 4.154; C. M. Jones, ‘The medical history of William Makepeace Thackeray’, ibid., 4.453–59). It is clear that he spent time in Paris with a woman ten or twelve years his senior whom he met at a masquerade ball. The experience may have been the inspiration for Pendennis's infatuation with both Emily Fotheringay, who was ten years his senior, and with Fanny Bolton—with the sexual element reduced to resisted temptation. Another apparently sanitized account of the meeting with Mlle Pauline appeared in Britannia on 5 June 1841. Thackeray left Cambridge without a degree in June 1830.

Seeking a career

Thackeray's bid for independence at the age of nineteen still entailed getting permission from his mother for his next venture: an extended stay in Germany, learning the language, reading, and getting to know societies other than his own. Intending to join the English society of Dresden, he ended at Weimar for six months, dressed in the uniform of a cornetcy of Devon yeomanry obtained for him by Major Carmichael-Smyth. He reported home on falling in love with two young ladies who abandoned him for better prospects; on meeting Goethe and the intellectual circle presided over by his daughter-in-law, Ottilie von Goethe; on studying German and things in general with Dr Friedrich August Wilhelm Wiessenborn; and on reading and translating Schiller's poetry. He undertook several writing projects but placed none.

Thackeray illustrated Schiller's poem about Pegasus in harness, drawing the winged horse with a cart, an image to which he returned repeatedly as indicative of his own relationship to high art. In Germany, Thackeray was, for the first time in his life, free to follow his own bent, and he cut a relatively successful figure of some grace and significance. Though German philosophy may have been too heavy for him, he was already imbibing the wisdom, scepticism, tolerance, and suspended judgement of Weimar's rather relaxed society. Though still a somewhat self-centred would-be English rake, he was already showing the tendencies of mind that led him to Victor Cousin's philosophy of uncertainty, which he read in 1832 (Colby, 27) and Montaigne's amused, detached observations of life in the Essays, which Thackeray read and reread throughout his life. On his return to England in the early summer of 1831, Thackeray spent a few weeks at Larkbeare before taking up law studies at the Middle Temple in June. He read law, clerked, attended dinners, and disparaged his work in letters home and to Edward Fitzgerald who occasionally came up to London to roam the streets and go to plays with him. He remained in this routine for nearly a year, during which his passion for the theatre and for reading fiction and history were developed more assiduously than the law. Losing any real ambition for the law, and without entrée to the circles of society which his expected fortune and his public school education led him to expect, he spent the year of his maturity in a variety of ‘ungentlemanly’ pursuits as bill discounter, desultory journalist, and artist. His friendship with Harry Kemble that year provided more dissipation, gambling, raucous nights—resulting in repeated entries in his diary vowing reform. His friendship with the editor of Fraser's Magazine, William Maginn, dates from 1832, when Maginn took him to a ‘common brothel where I left him, very much disgusted & sickened’ (Ray, Uses of Adversity, 156), but it is not clear that he was always to react so.

On coming of age on 18 July 1832 Thackeray's first business was to pay old gambling debts, a painful act which did not cure his craving for cards and dice. Nevertheless, with a fortune remaining at between £15,000 and £20,000, there was no reason for him to apply himself seriously to any profession that did not completely appeal to him. With the passage of the Reform Bill Thackeray joined Charles Buller in the campaign for a seat in parliament from Cornwall, which he undertook in spite of his allegiance to the tories and Wellington. Thackeray next spent several months in Paris, enjoying the independence of his inheritance, casting about pleasurably but without purpose, recording feelings of guilt and unhappiness in his diary.

Early in 1833 Thackeray purchased the National Standard for which he and James Hume, as sub-editor, provided the bulk of copy. After ten months the venture ended in failure, but Thackeray had joined the Garrick Club and got to know the London literati to whom he would return after yet another venture into France to take up his next ‘real’ profession: painting. His first attempt to study painting in Paris came in 1833, while he styled himself Paris correspondent for the National Standard, but it appears that his literary and artistic careers were both undertaken as fulfilments of pleasure by a man of some fortune. However, by December 1833 a series of bank failures in India wiped out the bulk of Thackeray's inheritance, leaving him without income. The Standard failed early in 1834, and Thackeray's second opportunity to study art materialized in September when his grandmother Butler moved to Paris and gave him a room. Embarking on what was supposed to be a three-year apprenticeship in the ateliers of a French artist, and thanking God for making him poor, Thackeray appears to have applied himself happily and seriously to his studies only to discover, within a year, that his talent for comic drawings would never develop into satisfactory art. This was a bitter disappointment to a man who had sacrificed a great deal of social pretension to follow a trade generally considered no better than ‘a hair-dresser or a pastry-cook, by gad’, as Major Pendennis remarks of Clive Newcome's parallel decision in The Newcomes. By the summer of 1835, virtually penniless, disgusted with his talent, with the vulgarity of his artist friends, with the moral degradation of his gambling cronies, one of whom committed suicide, and with his own repeated failures to reform or succeed, Thackeray's bohemian sojourn reached a nadir of depression.

Apprenticeship and marriage

But then Thackeray met Isabella Gethin Shawe (1816–1893), second daughter of Matthew Shawe, a colonel, who had died after extraordinary service, primarily in India, and his wife, Isabella Creagh. Isabella was living with her mother and sister on a pension in Paris. It was unlikely that any mother would encourage such a suitor as Thackeray, who, having moved from Mrs Butler's to a dingy den, consorted with painters and gamblers, without profession or expectations. Yet his love for Isabella appears to have focused Thackeray's attention on his condition and given him a purpose and drive that had hitherto been lacking. Through a sudden new industry Thackeray determined to win and wear Isabella as his wife. With the backing of his friend John Bowes Bowes, Thackeray published his first book—Flore et Zéphyr, a collection of captioned lithographs—which gained neither attention nor money. Then his stepfather became a major underwriter for a new journal of radical politics, the Constitutional and Public Ledger; this enabled Thackeray, as Paris correspondent, with an income of 8 guineas a week, to propose to Isabella in April 1836, and marry on 20 August.

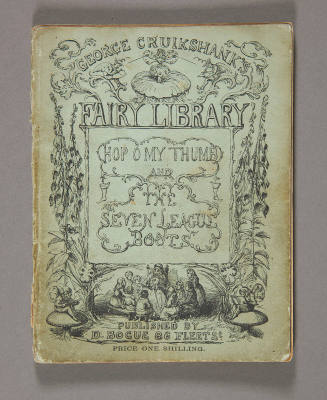

The marriage was, from all accounts, a very happy one, though beset by problems. The mother-in-law, never happy about losing her daughter, especially to Thackeray, proved a virago, serving amply as prototype for the gallery of horrid mothers-in-law in Thackeray's fiction. Then the Constitutional failed, leaving the future novelist—now responsible for a small family—without support except what could be gained by freelance writing. He took his bride to London and began ten years of heavy hack work, living from hand to mouth and suffering one domestic and financial disaster after another. Three daughters were born, Anne Isabella, later Lady Ritchie (1837–1919), a novelist in her own right, in 1837, Jane (who died at eight months) in 1838, and Harriet Marian (‘Minnie’, later the wife of Leslie Stephen) [see Stephen, Harriet Marian] in 1840. Jane's death, Minnie's birth, and an apparent genetic tendency brought on serious depression in Isabella. This was compounded by feelings of worthlessness as mother, wife, and housekeeper and by neglect from Thackeray; finding he could get no work done at home, he spent more and more time away, researching for his travel narratives and writing essays and stories, primarily for Fraser's Magazine. From the demise of the Constitutional in July 1837 to the end of 1840 Thackeray published ninety magazine pieces and his first book, The Paris Sketch Book; he also signed a contract for a book in two volumes on Ireland. During the same time two books of reprints were published, though without benefit to his purse (The Yellowplush Correspondence in Philadelphia and a pamphlet on George Cruikshank). Perhaps this frantic activity kept Thackeray from noticing anything special about his shy wife's condition, but in mid-August 1840, on his return from a two-week trip in the Low Countries gathering materials for a guidebook never written, he was alarmed by his wife's languor and depression.

Two radical changes then affected Thackeray's life: he turned his attention from his work to his ailing wife, and his sense of guilt appears finally to have produced a profound effect on his personality and behaviour well beyond repeated self-recriminations in a diary. His attention to Isabella and his daughters and his acceptance of his part in creating their condition and his responsibility for their future raised his consciousness about their restraints and vulnerabilities, their worth and potential, and about the self-important self-centredness of his own life as well as that of ordinary men, his peers, whose birthright was to enjoy life and use wives and other women kinsfolk as superior servants. Beginning with The History of Samuel Titmarsh and the Great Hoggarty Diamond (serialized from September 1841), his narratives of young men pursuing normal courses of self-fulfilment depict more and more accurately the women who suffered and supported them. Sam Titmarsh's fortunes flare and funk, leaving him chastened and dependent on his resourceful, strong, and loving wife, whose economic contribution to the family equals her husband's. Mary Titmarsh may be based in part on Isabella, but unlike the novelist's wife she proved more resilient and sensible than her husband. Arthur Pendennis, the ‘hero’ of Thackeray's second major work and the narrator of most of his subsequent books, constitutes a major study of masculine self-absorption, learning and relearning and then forgetting to understand the cruelties to women that passed as ordinary behaviour for sons, lovers, husbands, and fathers.

In September Thackeray took the ailing Isabella to Ireland, hoping that the company of her mother and sister Jane would help restore her spirits. During the crossing Isabella threw herself from a water-closet into the sea, from which she was eventually rescued; it was no longer possible to avoid recognition of her mental breakdown. The Irish sojourn, originally planned as a research trip for The Irish Sketch-Book, turned into a domestic battle with the mother-in-law from which Thackeray and Isabella fled after four weeks. In debt to his grandmother and indebted in incalculable ways to his children's nurse, Brodie, who gave up wedding plans to continue caring for the distressed family, Thackeray was also in receipt of an advance from Chapman and Hall for an Irish book which he had been unable to research or write. He returned to his parents in Paris, where he managed, over the next six months, to write ten magazine pieces, a small book (The Second Funeral of Napoleon), a serial novelette (The History of Samuel Titmarsh), and several chapters of a novel never finished (The Knights of Borsellen). From November 1840 to February 1842 Isabella was in and out of professional care, her condition waxing and waning, but in the long run deteriorating until she was placed with Dr Puzin at Chaillot, where she lapsed into a stable, detached condition, unaware of the world around her.

The experience of his mother-in-law's cruelties in contrast to the support of Brodie, his own mother, and Mary Graham Carmichael created in Thackeray deep understanding of women's capacities for cruelty, devotion, generosity, and demands. These insights are apparent in his complex portraits of women such as Amelia Sedley and Helen Pendennis, who exact dreadful tolls from the men they control through helpless love; of women like Blanche Amory, Becky Sharp, and Beatrix Esmond, who exercise control through imperious sexuality; and of women such as Ethel Newcome and Laura Pendennis, whose native intelligence and humour are the objects of male repression and societal control. All these women have secret depths, intelligence, and emotional complexities that Thackeray reveals in ways that some readers have taken to be inconsistency of characterization.

In the six years from the manifestation of Isabella's insanity at the end of 1840 to the start of the serial publication of Vanity Fair in January 1847, Thackeray published 386 magazine pieces and three books, all under pseudonyms. There are over twenty known pseudonyms, the most famous and clearly differentiated being George Savage Fitzboodle, Michael Angelo Titmarsh, Major Gahagan, Ikey Solomons, and Charles James Yellowplush. Thackeray's use of pseudonyms allowed him to develop a remarkable range of ventriloquist voices and a habit of presentation which dominated the later works, written in the person of Pendennis, an admitted alter ego who undergoes subtle analysis and complex criticism by the ‘author’ whose defences of Pendennis are full of apparently deliberate holes. Some would argue that this is a clumsy and inept narrative technique, allowing readers to equate Pendennis with his creator and to conclude, therefore, that Pen's false starts and contradictions represent Thackeray's lack of control over his medium. To those who hold a more charitable view, that Thackeray presents an ironic vision above and beyond that of his narrator, the effect is a sense of ever-increasing narrative complexity and subtlety, a finer and sharper criticism of social conventions.

Having placed his wife in the care of Dr Puzin in 1842 Thackeray returned to London, leaving his daughters for the next four years with his mother in Paris. London was where he could earn by writing what was needed to support his family and make his way in the world. At first he lived in the family house at 13 Great Coram Street, which he shared uneasily with his cousin Mary and Charles Carmichael. His first contribution to Punch appeared, but almost immediately he undertook the long deferred research trip to Ireland, spending five months there. Though he had reviewed the Irish novelist Charles Lever rather roughly, their meeting was cordial and their friendship lasted for life. Thackeray dedicated The Irish sketch-book to Lever, who reviewed it admiringly in the Dublin Review, though he obviously had reservations about the portrait of Ireland, and he later caricatured Thackeray as Elias Howle in Roland Cashel. Willingness to tilt irreverently at older, better-known novelists had already landed Thackeray in hot water with Edward Bulwer, later Lord Lytton; for in Yellowplush (1837) he lampooned Bulwer's inflated literary style and attributed to him grossly inflated self-aggrandizement. When the Yellowplush papers were reprinted in New York in 1852, Thackeray wrote a preface apologizing for the unfairness of the portrait and wrote Bulwer a letter at the same time. In 1855 a collection of Thackeray's Miscellanies published both in London and on the continent of course included the Bulwer lampoons again. Apologies aside, Thackeray never actually recanted his attitude toward Bulwer's style.

On his return to London Thackeray gave up the house, moving first to a hotel and then to fourth-floor lodgings in Jermyn Street. He next undertook trav

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Clifton, England, 1821 - 1896, London

Black Bourton, England, 1768 - 1849, Edgeworthstown, Ireland

Baltimore, 1838 - 1915, New York

Bredfield, England, 1809 - 1883, Merton, England