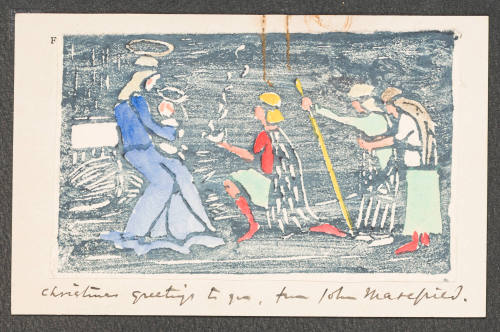

John Masefield

Ledbury, England, 1878 - 1967, near Abingdon, England

Masefield, John Edward (1878–1967), poet and novelist, was born at The Knapp, Ledbury, Herefordshire, on 1 June 1878. He was the third of the six children of George Edward Masefield (1842–1891), solicitor, and his wife, Caroline Louisa Parker (b. 1852). His mother died following childbirth in 1885, after which his father became increasingly unbalanced, until his own death in hospital in 1891. The children were brought up by an uncle and an aunt (who tried to repress Masefield's addiction to reading), and by a succession of governesses. Nevertheless, his early years in the Herefordshire countryside were very happy ones (Smith). In 1888 he was sent to Warwick School and then, in 1891, to HMS Conway in Liverpool, to train as an officer in the merchant marine. Life there was rough and he did not escape bullying, though there were compensations too, and he took delight in the great sailing ships.

In 1894 Masefield sailed for Chile, via the Cape, on the four-master Gilcruix, an experience on which he later drew in one of his finest narrative poems, Dauber (1913). But despite his love of the sea he was an indifferent sailor and was eventually shipped home as a DBS—‘distressed British seaman’. Soon after this, on another voyage, he jumped ship in New York to travel rough in the United States. This was followed by a spell as a barman in Greenwich Village and then by steadier work in a carpet factory in Yonkers. While in New York, Masefield read voraciously, and with the help of the local booksellers discovered such favourite authors as Chaucer, Malory, and the Romantic poets. It was at this time that he realized that poetry was his vocation. On 4 July 1897 he returned to England with, as he said, ‘£6 and a revolver’ (Smith, 49), determined either to find work or to shoot himself.

Back in London, Masefield began to write seriously while working as a clerk. He first attracted attention with Salt-Water Ballads (1902), Ballads (1903), and, in 1910, Ballads and Poems. Some of these poems, such as ‘Sea-fever’ and ‘Cargoes’, have remained popular ever since, providing the first introduction to poetry for generations of school children. Coming after the verse of the fin de siècle, they are strikingly vigorous. Like Kipling, Masefield celebrates the common man—as his poem ‘A Creed’ puts it, ‘Not the ruler for me, but the ranker’—though his focus is on England itself rather than the empire. A poem that was especially important to him is ‘The Wanderer’, which depicts the beauty and decline of the tall ships, thus initiating the theme of defeated endeavour to which he often returned in later books. A crucial event of these early years was Masefield's meeting with W. B. Yeats in 1900, and through him with J. M. Synge in 1903. With Yeats he found literary companionship and an entry into the literary world. Soon after, in 1901, he became a full-time writer.

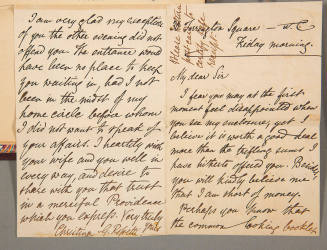

Masefield married Constance de la Cherois Crommelin (1866/7–1960) on 23 July 1903 in London. She was Irish, of French Huguenot descent, eleven years older than he, and considerably better off. She was a graduate of Newnham College, Cambridge: at the time of the marriage she was the proprietor of a girls' school in London, having previously been senior mistress at Roedean. She had some influence on Masefield's social views, particularly on women's suffrage. They had a daughter, Judith (1904–1988), a book illustrator, and a son, Lewis (b. 1910), a novelist, who died in action in north Africa in 1942. Masefield had many relationships—all platonic as far as is known—with other women, often with women older than himself, such as the actress Elizabeth Robins, to whom at one point he wrote as often as nine times in a day, and Florence Lamont, who supported his theatre work, and with whom he had an important correspondence.

In 1911 Masefield published The Everlasting Mercy, which has been described as ‘a bigger literary sensation than ... Barrack-Room Ballads’ (Spark, 3). It is certainly quite unlike most of the verse of the period. Its story of a reformed wastrel was widely admired and debated for its ‘low’ comic dialogue and its revelation of the more squalid side of rural life. The brutally realistic boxing bout is enough to cast doubt on the notion that Masefield was ever a ‘Georgian’ poet. The poem was attacked by clerics, but it was also recited in public houses in the East End of London—not usually an audience for modern verse.

The second decade of the twentieth century saw the publication of most of Masefield's finest verse. Dauber appeared to similar acclaim in 1913. Its demotic dialogue and the vivid description of a storm off the Cape show Masefield as both a naturalist and a romantic, having learned from Conrad and Melville, as well as from Kipling. Indeed, he always saw himself as a teller of tales. In old age he told Muriel Spark that, ‘My main concern has always been to tell stories ... to living audiences’ (Spark, 80–81). At the outbreak of the First World War Masefield, who had previously had pacifist leanings, went with the British Red Cross to the Dardanelles; on his return he published Gallipoli (1916), one of the finest accounts we have of modern warfare. Though an ‘official’ commission, it gives a graphic insight into the life of the common soldier, in both its horror and its heroism. During the war Masefield went to the United States, under government auspices, to help to explain the British war effort, and in 1917 he received honorary doctorates from both Yale and Harvard universities, the first of many such awards. At this time he declined a knighthood (and did so again several times in later years). He preferred to be a common man himself, as well as a poet of the common man.

Masefield's most popular poem, Reynard the Fox, appeared in 1919. It is less disturbing than Dauber, and was perhaps a reaction to the horrors of war. Amy Lowell called it ‘a cry of hunger for the past’ (Sternlicht, 70), though there is nothing dreamy or ruminative in its nostalgia for rural England. The inspiration for the meet is clearly Chaucer's ‘Prologue’, and the hunt itself, seen from the fox's point of view, is as full of pace and dash as of pathos. Perhaps the greatest pleasure the poem offers lies in its observant relish of the natural world. Masefield wrote other fine narrative poems in those years, such as The Widow in the bye Street (1912) but none was so successful. At the same time he was also producing work of many other kinds, from naval history to his essay on Shakespeare as a poet (1911).

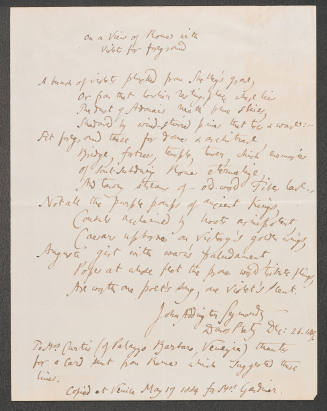

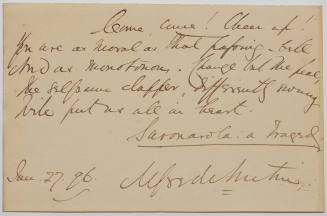

From 1905 until 1926 Masefield was also deeply involved with drama, partly as a result of the influence of Yeats and Synge. His most successful play was The Tragedy of Nan (1909); however, his theatrical work received at best a mixed response. It ranged from versions of Racine to dramas on the life of Christ and involved him in collaborations with, among others, Granville Barker and Gilbert Murray. Perhaps the most significant aspect of these activities was Masefield's championship of live poetry reading. He set up his own theatre in his house at Boars Hill, near Oxford, to which he had moved in 1917, and invited many friends (and successive generations of Oxford undergraduates, including Robert Graves, whose landlord he was) to his productions. Some of this work was continued when he became poet laureate in 1930. This honour set the seal on his popularity and he took its responsibilities more seriously than many of his predecessors had done. Apart from writing much occasional verse, he read his poetry in public widely and often. He also worked tirelessly as president of the Society of Authors (from 1937) and of the National Book League (1944–9). In 1935 he was appointed to the Order of Merit.

Masefield was never simply a poet. He was also a prolific novelist for most of his writing life, particularly novels of action, which ranged, as his poems did, from eighteenth-century seaports to ancient Troy and beyond. Among his most rewarding novels are Lost Endeavour (1910), The Bird of Dawning (1933), and the uncanny Dead Ned (1938). Great claims cannot be made for his fiction, but it is nearly always readable and often vivid. He is better known now as an author of children's books, the best of which, such as The Midnight Folk (1927) and The Box of Delights (1935), have become classics. Beside all this, he regularly published verse—right into old age. He no doubt wrote too much, but there are good poems in all his later books, albeit less vigorous ones than those of his best period. Masefield also wrote several memoirs in his later years, although these tend to conceal as much as they reveal of his early days. By the end of his life his Collected Poems had sold over 200,000 copies—an unprecedented figure for a modern poet, indicating his popularity with ordinary readers. He was also a tireless letter writer; one scholar has estimated that he wrote no fewer than 250,000 letters.

Masefield was essentially a traditional poet and he always thought of himself as a Victorian. He relied on conventional forms and metres and he addressed his verse to the common reader rather than to the literati. After he became laureate his work went increasingly out of fashion; but more recently it has begun to be rediscovered. Readers have ventured beyond the more ‘poetical’ later verse to what Edward Thomas called the ‘fidelity to crudest fact’ (p. 116) of his best work. Masefield's narrative poems are particularly admired. However, his audience now seems mainly confined to devotees of pre-modernist verse, to the general reader, and to schools. His name is not one that figures largely in critical accounts of modern poetry, nor is it much cited by contemporary poets. Masefield's work has perhaps been the victim of its own popularity: many readers do not realize that at its best it is both more challenging and more modern than its conventional reputation would suggest.

In appearance Masefield was tall, thin, and blue-eyed, with what one friend called ‘an expression of perpetual surprise’ (Spark, 32). Everyone remarked on his courtesy and friendliness. His manner was simple and unaffected—never that of ‘the laureate’ or the ‘great man’. He took special pleasure in helping younger writers.

Masefield's wife, Constance, died in 1960 and Masefield himself died on 12 May 1967, at Burcote House, his home near Abingdon, as a result of a gangrenous foot which he refused to have amputated. His daughter looked after him in his final years. On 20 June 1967 his ashes were interred in Westminster Abbey, London, in Poets' Corner, next to Browning's. Another memorial to him might be his own early poem ‘Biography’ (1912):

When I am buried, all my thoughts and acts

Will be reduced to lists of dates and facts.

Masefield cherished the storyteller's traditional anonymity.

David Gervais

Sources

C. B. Smith, John Masefield: a life (1978) · G. Handley-Taylor, John Masefield OM: a bibliography (1960) · C. Lamont, Remembering John Masefield (1971) · S. Sternlicht, John Masefield (1977) · M. Spark, John Masefield (1953) · F. Drew, John Masefield's England (1973) · P. Carter, correspondence, Masefield Society · J. Masefield, In the hill (1941) · J. Masefield, New chum (1944) · J. Masefield, On the hill (1949) · J. Masefield, So long to learn (1952) · J. Masefield, In glad thanksgiving (1967) · A language not to be betrayed: selected prose of Edward Thomas, ed. E. Longley (1981) · b. cert. · m. cert. · d. cert.

Archives

Bodl. Oxf., corresp., papers, and literary MSS · Bodl. Oxf., letters to his family · Bodl. Oxf., papers relating to battle of the Somme · Harvard U., Houghton L., corresp., papers, and literary MSS · Hereford City Library, MSS · Hunt. L., letters · L. Cong., letters · London Library, letters · LUL, Sterling Library, MSS · LUL, watercolours and drawings, photographs and papers · New York University, Fales Library, letters · NL Scot., letters · University of Arizona, Tucson, corresp. · V&A, theatre collections, letters · V&A, theatre collections, letters and papers relating to The coming of Christ · Yale U., Beinecke L., letters and literary MSS :: BL, corresp. with Sir Sydney Cockerell, Add. MS 52735 · BL, letters to Harley Granville-Barker, Add. MS 4789 · BL, corresp. with League of Dramatists, Add. MS 56854–56856 · BL, letters to Lillah McCarthy, Add. MS 47897 · BL, letters to George Bernard Shaw, Add. MS 50543 · BL, corresp. with Society of Authors, Add. MSS 56575–56626 · Bodl. Oxf., letters to Robert Bridges · Bodl. Oxf., letters to Celia Brown · Bodl. Oxf., letters to Nevil Coghill · Bodl. Oxf., letters to J. L. L. Hammond · Bodl. Oxf., letters to Phyllis Horne · Bodl. Oxf., letters to Grace Hunter · Bodl. Oxf., corresp. with Gilbert Murray · Bodl. Oxf., corresp. with Audrey Napier-Smith incl. two albums of watercolours and photographs · Bodl. Oxf., corresp. with H. W. Nevinson and E. S. Nevinson · Bodl. Oxf., letters to James Shelley · Bradford Art Galleries and Museums, letters to Butler Wood · CAC Cam., letters to Cecil Roberts · Col. U., letters to Cyril Clemens and literary MSS · CUL, letters to Siegfried Sassoon · Dorset County Museum, Dorchester, letters to Florence Hardy · Forbes Magazine, New York, corresp. with John Galsworthy · Harvard U., Houghton L., letters to Sir William Rothenstein · JRL, letters to Manchester Guardian · King's AC Cam., letters, mainly to Charles Ashbee · King's AC Cam., letters and postcards to Rupert Brooke · Litchfield Historical Society, Connecticut, letters to Dorothy Bull · London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, corresp. with Sir Donald Ross · LPL, letters to G. K. A. Bell · LUL, corresp. with Thomas Sturge Moore · LUL, letters to Ethne Thompson · News Int. RO, corresp. with The Times · NL Scot., letters to Lilian Adam Smith · NL Scot., letters to Alice V. Stuart · PRONI, letters to Margaret Dobbs, Mic 152 · Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow, corresp. with Sir Ronald Ross · Royal Society of Literature, London, letters to Royal Society of Literature · U. Birm. L., letters to Ada Galsworthy · U. Birm. L., letters to Francis Brett Young · U. Leeds, Brotherton L., letters to Edmund Gosse · U. Leeds, Brotherton L., letters to Thomas Moult · University of Kent, Canterbury, letters to Hewlett Johnson

SOUND

BL NSA, performance recordings

Likenesses

W. Strang, oils, 1912, Man. City Gall. · A. L. Coburn, photogravure, 1913, NPG · E. Kapp, drawing, 1917, Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham · W. Rothenstein, drawing, 1920, FM Cam. · J. Lavery, oils, 1937, priv. coll. · H. Coster, photographs, 1940–50, NPG · F. Man, photograph, c.1945, NPG · M. Gerson, photograph, 1961, NPG · H. Lamb, pencil drawing, NPG · T. Spicer-Simson, plasticine medallion, NPG · W. Strang, etching (after his oil portrait, 1912), NPG [see illus.] · W. Strang, oils, Wolverhampton Art Gallery · portraits, repro. in William Strang RA [1980] [exhibition catalogue, Sheffield, Glasgow, and London, 6 Dec 1980 – 28 June 1981]

Wealth at death

£71,162: probate, 6 Nov 1967, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–16

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

David Gervais, ‘Masefield, John Edward (1878–1967)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Sept 2013 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/34915, accessed 20 Oct 2017]

John Edward Masefield (1878–1967): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34915

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Surbiton, Surrey, 1863 - 1920, London

Walmer, England, 1844 - 1930, Oxford, England

Bristol, 1840 - 1893, Rome

Partick, Scotland, 1872 - 1948, Monte Carlo

Fockbury, England, 1859 - 1936, Cambridge, England

London, 1830 - 1894, London

Headingley, England, 1835 - 1913, Ashford, England

Great Yarmouth, 1824 - 1897, London