Image Not Available

for Henry Taylor

Henry Taylor

Bishop Middleham, England, 1800 - 1886

Taylor, Sir Henry (1800–1886), poet and public servant, was born on 18 October 1800 at Bishop Middleham, co. Durham, the youngest of three sons of George Taylor (1772–1851), gentleman farmer and classicist, and his first wife, Eleanor Ashworth (d. 1801?), the daughter of a Durham ironmonger who shared her husband's literary interests. Shortly before his wife's death, George Taylor had resettled his family at St Helen Auckland, where he farmed and pursued his classical studies for the next eighteen years, publishing an occasional essay in the Quarterly Review. Although preferring a quiet, retired life, George Taylor served briefly as secretary to the commission on the poor laws in the early 1830s before family concerns forced his resignation. In 1818 he married Jane Mills (1770–1853), long-time family friend; she became a devoted companion and adviser to the young Henry, though unfortunately she was as emotionally reserved as his father. On his marriage George Taylor moved to the village of Witton-le-Wear, where he lived until his death thirty-two years later.

In his Autobiography Henry Taylor describes his childhood home as sombre, marked by his father's melancholy following the death of his first wife. George Taylor educated his three sons at home, and Henry confessed that by comparison with his talented, older brothers he proved an indifferent scholar, acquiring, literally, little Latin and less Greek. In 1814 his father permitted him to follow his desire to go to sea. In April he went aboard the Elephant as a midshipman, later being transferred to a troopship and finally a frigate; between them these postings took him to Canada and near the United States at the end of the Anglo-American War of 1812–14. In December he was discharged, finding life aboard ship suited neither his character nor his health. He returned home where he read widely in his father's library. When he was sixteen, he obtained, through the offices of Charles Arbuthnot, then secretary of the Treasury and a family friend, a clerkship with the storekeeper-general. At first he lived in London with his brothers until, in 1818, they contracted typhus and died shortly after within the same month. Following their deaths, Henry continued for a short while in London on his own before being transferred to Barbados. His duties came to an end in 1820 when his department was consolidated with another branch of the Treasury, and he returned a second time to his father's house.

For the next three years Taylor lived quietly at home. Looking back, he called this time ‘dull, almost to disease’ (Autobiography, 1.43). He filled his days with miscellaneous reading, ranging from Machiavelli and Hume to the Koran and Milner's Church History. He also improved his Latin and Greek and taught himself Italian, translating Ariosto and reading widely in Italian poetry. At night he devoted himself to writing his own poetry. He had read the popular poets and novelists of the day—Scott, Byron, Moore, and Campbell—and composed long narrative poems on exotic topics in the manner of Byron. He also wrote his first verse drama, a tragedy on the story of Don Carlos. Apart from these Byronic juvenilia, he began his literary career in earnest. In 1822 he made his publishing début, submitting an essay on Moore's Irish Melodies for the Quarterly Review. The Quarterly editor William Gifford invited his new contributor to submit another essay, which he soon did. He also found his articles welcome at the London Magazine. The success of these first attempts at journalism encouraged him to venture to London in 1823 to earn his living by his pen. These early literary efforts were encouraged by his stepmother and her cousin Isabella Fenwick, a woman of independent means who was for many years a close friend and neighbour of Wordsworth and, while Taylor's senior by some years, one of his most intimate literary confidantes until her death in 1856.

During the early 1820s Taylor began to form friendships with important literary contemporaries as well. He met and corresponded with Wordsworth, visited Coleridge often at Highgate, and developed an especially close bond with Southey, despite differences of age, temperament, and politics. The two toured Holland, France, and Belgium in 1825 and again in 1826, and Southey wrote the only favourable review of Taylor's first published drama, Isaac Comnenus (1827). In London, Taylor also became a frequent guest at Samuel Rogers's literary breakfasts, and he joined the debate society frequented by John Stuart Mill, Charles Austin, and other ‘radical, Benthamite, doctrinaires’ (Autobiography, 1.77) where he spoke against Benthamite principles and for pragmatic reform.

Taylor's need to earn a living by writing was permanently altered in 1824 when Sir Henry Holland recommended him for a clerkship in the Colonial Office, based on his prior colonial experience as well as his literary abilities. Taylor immediately distinguished himself and in January 1825, despite his youth, was appointed senior clerk for the Caribbean colonies (initially at £600 per annum, later £900), a post he held until his retirement in 1872. In the Colonial Office at that time his status as a senior clerk gave him certain privileges. Colonial secretaries and under-secretaries allowed a large part of the administrative load to devolve on the senior clerks. Taylor even had direct access to the colonial secretary, especially during the period (1846–52) when his friend Henry George, the third Earl Grey, held the post.

Taylor dealt with the West Indian colonies during the agitation that led to the end of slavery in 1834, the brief but troubled apprenticeship period that followed, and the subsequent difficulties of a post-slavery society. Taylor supported emancipation, but distrusted the ability of black West Indians to be self-governing. As a result, he favoured an apprenticeship plan to effect a transition from slavery to freedom as well as safeguards against what he foresaw as abuses by the planters who remained in control of local assemblies, except in crown colonies. When abuses led to a premature end of the apprenticeship period in 1838, Taylor argued that West Indian assemblies needed to come more directly under crown control or he predicted disaster would follow. For Taylor, the 1865 Gordon riots in Jamaica were exactly that disaster, and resulted in the Jamaican assembly relinquishing sovereignty to the crown, a move he had argued for in 1838 and that he claimed would have prevented such riots. While he supported Governor Eyre's controversial restoration of order following the Gordon uprising, the uprising itself was in his mind the inevitable result of failed policies.

Taylor took little part in the political questions of the day, except on two notable occasions: first, when he came to the defence of his close friend Charles Eliot, British plenipotentiary in China, who in 1840 was attacked in both parliament and the press for ‘gunboat’ diplomacy to protect British merchants, an action which precipitated the First Opium War; and, second, when he published a pamphlet, Crime Considered (1869), addressed to Gladstone, then prime minister, on certain proposed reforms in the penal code, especially as they applied to the colonies, including his controversial support for corporal punishment.

Taylor was an astute observer of the day-to-day workings of government bureaucracy, and he published a frank yet ironic look at those operations in The Statesman (1836), a work composed of maxims and practical advice based on his career in the civil service. The manuscript was reviewed by his Colonial Office colleagues and friends, Edward Villiers, James Spedding, editor of Francis Bacon, and Gladstone. Contemporaries regarded the work as too cynical, even Machiavellian, but it has since become something of a minor classic, remaining in print throughout the twentieth century. Taylor's superiors offered him advancement, including the under-secretaryship, but various reasons always kept him from taking advantage of proffered promotion. In 1859, when a severe asthmatic attack nearly forced his retirement, he was allowed to work at home rather than in the Downing Street offices.

Working in the Colonial Office brought Taylor friendships with a number of the leading statesmen of the time. One particular friendship with Thomas Spring Rice, secretary for war and colonies in Melbourne's first cabinet, eventually led to his marriage to the secretary's daughter Theodosia Alice Spring Rice (1818–1891) on 17 October 1839, following a three-year courtship marked by a break in relations owing to Taylor's religious diffidence. Despite their differences in age (he was nearly twenty years her senior), their home life was by all accounts happy and affectionate, full of the pleasure of company and friends and the complete opposite of the sombre home of his youth. The couple settled first in London, in Blandford Square, moving in 1845 to Ladon House at Mortlake on the Thames. In 1853 they built a house designed by Alice abutting Sheen Common where they lived until Taylor's retirement. They had five children. The eldest son, Aubrey, died on 16 May 1876, and a daughter, Una, wrote Guests and Memories (1924), a memoir about her parents, their Bournemouth summer home purchased in 1861, and the notable guests they entertained there, in particular, Aubrey De Vere, James Spedding, Benjamin Jowett, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Mary Shelley and her son Sir Percy. Their eldest daughter was the biographer Ida Alice Ashworth Taylor.

Despite his appointment in the Colonial Office and the often long hours required of him there, Taylor pursued his career as a poet, publishing five novel-length verse dramas and a volume of lyric poems. Following the failure of Isaac Comnenus, Taylor worked for seven years on his next historical drama and produced his greatest success in 1834 with the publication of Philip Van Artevelde, a tale drawn from Froissart and Barante in which he blends political conflict with domestic drama in an Elizabethan style but with a modern emphasis on psychological states more than dramatic action. In Van Artevelde Taylor also championed a more restrained poetic style against what he regarded as the excesses of the school of Byron and Shelley. Aware of going against popular taste, he provided Van Artevelde with a preface that set forth at length his critique of Byron and Shelley whose poetry, despite its powerful feeling and beautiful imagery, lacked, in his view, moral reflection and the balance of passion with reason. For his contemporaries, the ‘Preface’ to Philip Van Artevelde signalled a significant shift in poetic taste, corresponding to Carlyle's call to set aside Byron for Goethe.

The publication of Van Artevelde was widely and extensively reviewed, including in the Revue des Deux Mondes. It brought Taylor immediate fame, and he was briefly lionized by Lady Holland and other London hostesses, and was ever afterwards referred to by close friends as Philip Van Artevelde Taylor. His contemporaries compared the accomplishment to Shakespeare's, and William Macready was so taken by the work that he staged an abridged version which, however, ran for only six nights. But Taylor never again achieved the popular success of Philip Van Artevelde. In 1842 he published Edwin the Fair, a work even he came to regard as deficient in dramatic interest. For his next play Taylor attempted an Elizabethan romantic comedy, The Virgin Widow (1850). He published only one other drama, St Clement's Eve (1862), a return to Barante as a source and his most successful work since Van Artevelde. Although his work is uneven, he did win the regard of contemporaries, including admirers as different as Macaulay and Swinburne, the latter being so genuinely impressed by the historical dramas he sought out the elderly poet's company and friendship in the 1870s. A collected edition of his work in five volumes appeared in 1877–8, but following his death his poetry quickly sank into obscurity and has not been reprinted since.

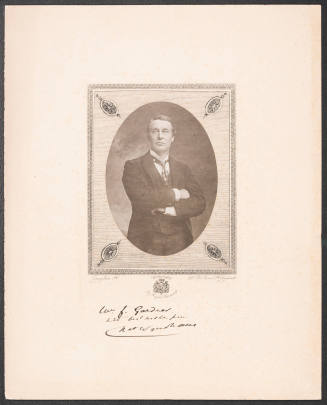

In his later years Taylor received a number of honours. Oxford University awarded him the DCL in 1862 and he was made KCMG in 1869 for his contributions in the Colonial Office. Although he stopped writing poetry, he did revise his plays for the collected edition, and continued to see close friends, such as De Vere, Tennyson, and his irrepressible Freshwater neighbour Julia Margaret Cameron, who found his features extremely handsome and used him frequently as a model for her photographs. He died at his home, The Roost, Bournemouth, on 27 March 1886, survived by his wife, who died on 1 January 1891, and his youngest son Harry and three daughters.

Taylor sought fame as a poet, yet, ironically, it is his prose which has remained significant. His Autobiography has proved invaluable to historians of the Colonial Office and West Indian affairs. Likewise, The Statesman provides a portrait of the Colonial Office and civil service in the years preceding the Northcote–Trevelyan report. Even of his historical dramas, only the ‘Preface’ to Philip Van Artevelde is still read and then as a classic statement of the shift in taste from Romantic to Victorian, even though the play itself, among all Taylor's work, is most deserving of being remembered. In her photographs Julia Margaret Cameron appears to have given Taylor a fame more lasting than any of his writings, as she has immortalized the calm face, pensive eyes, and magnificent flowing beard he grew after the 1859 asthmatic attack left him unable to shave.

Mark Reger

Sources

H. Taylor, Autobiography, 1800–1875, 2 vols. (1885) · U. Taylor, Guests and memories: annals of a seaside villa (1924) · Correspondence of Henry Taylor, ed. E. Dowden (1888) · W. Ward, Aubrey de Vere: a memoir (1904) · D. M. Young, The colonial office in the early nineteenth century (1961) · D. J. Murray, The West Indies and the development of colonial government, 1801–1834 (1965) · W. L. Burn, Emancipation and apprenticeship in the British West Indies (1937); repr. (1970) · DNB · H. G. Merriam, Edward Moxon: publisher of poets (1939) · M. Weaver, Julia Margaret Cameron, 1815–1879 (1984) · The Times (30 March 1886), 10

Archives

BL, MS autobiography, Add. MS 39179 · Bodl. Oxf., corresp., papers, diaries, and literary MSS · Bodl. Oxf., letters · Hunt. L., letters · U. Durham L., papers concerning slavery :: BL, corresp. with W. E. Gladstone, Add. MSS 44355–44490, passim · BL, letters to Lord Stanmore, Add. MSS 49199, 49236, 49240 · Bodl. Oxf., corresp. with James Ingram; corresp. with Lord Kimberley · CUL, corresp. with Sir James Stephen · NA Canada, letters from Sir Thomas Frederick Elliot · NL Scot., corresp. with A. R. D. Elliot; corresp. with Sir T. F. Elliot · NL Scot., letters to Sir Alexander Hope · NL Scot., corresp. with Lady Minto · TCD, letters to W. E. H. Lecky and Elizabeth Lecky · U. Durham L., corresp. with third Earl Grey · Wordsworth Trust, Dove Cottage, Grasmere, letters to Wordsworth family

Likenesses

L. Macdonald, marble bust, 1843, NPG · J. M. Cameron, photographs, 1864–7 · J. M. Cameron, photograph, 1865, NPG [see illus.] · O. Rejlander, carte-de-visite, NPG · G. F. Watts, oils, NPG · photographs, Bodl. Oxf., Sir H. Taylor album of Cameron photographs

Wealth at death

£7719 6s. 4d.: probate, 13 May 1886, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–16

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Mark Reger, ‘Taylor, Sir Henry (1800–1886)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/27030, accessed 24 Oct 2017]

Sir Henry Taylor (1800–1886): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27030

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Terms

Coventry, England, 1847 - 1928, Tenterden, England

Liverpool, England, 1808 - 1876, Menton, France

Sydney, Australia, 1866 - 1957, Boars Hill, England

Warwick, 1775 - 1864, Florence