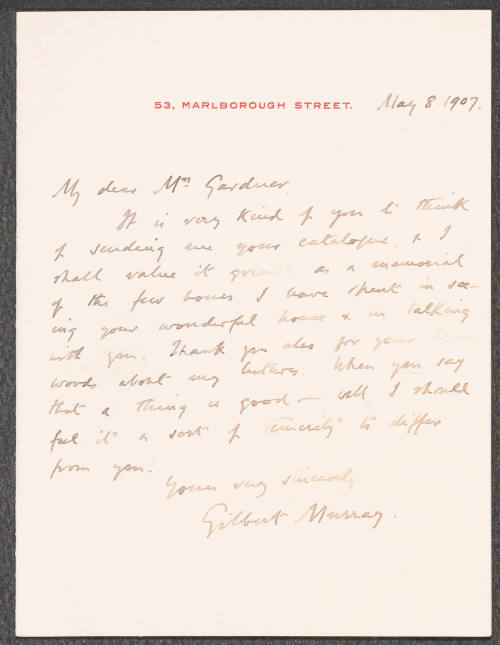

Gilbert Aimé Murray

Sydney, Australia, 1866 - 1957, Boars Hill, England

Murray, (George) Gilbert Aimé (1866–1957), classical scholar and internationalist, was born in Sydney, Australia, on 2 January 1866, the second son of Sir Terence Aubrey Murray (1810–1873) and his second wife, Agnes Ann, née Edwards (c.1835–1891). Murray's father, a prosperous stock farmer, had been since 1862 president of the legislative council of New South Wales; his elder brother Sir (John) Hubert Plunkett Murray (1861–1940) later became governor of Papua. The family thus belonged to a colonial élite, though Murray's paternal ancestors had been expropriated from their Irish estates by the English in the seventeenth century and the Murrays thus tended to be ‘agin the government’. Murray's first name came not from W. S. Gilbert, as has been supposed, but from another maternal relative, Gilbert Edwards. In his childhood and youth Murray was known as George; he became Gilbert on his marriage in 1889. In 1875 he was sent to Southey's, a boarding-school 80 miles from Sydney. The bullying of pupils and mistreatment of animals he witnessed there prompted a lifelong detestation of cruelty in any form.

Education and marriage

As Sir Terence's fortunes declined, the Murrays moved into progressively smaller houses. Four years after his father's death in 1873 George was taken to England by his mother to complete his education. This began with a year at a dame-school in Brighton and continued at Merchant Taylors' School, one of the nine leading (Clarendon) public schools, then still in London. Here Murray did well in rugby and won several prizes for his work as well as learning a little Hebrew. Francis Storr, head of the modern (non-classical) side of the school and an intelligent Liberal, became a strong influence and a friend. Murray now began to read Spencer and Comte, and especially J. S. Mill, a lifelong influence, whose philosophical radicalism was reinforced for Murray by the idealism of Shelley. In 1884 he went on to St John's College, Oxford, to which the school was linked, with scholarships which eased a financial burden his mother could hardly have borne.

Already an accomplished composer in Latin and (especially) Greek, Murray was coached before he went up to Oxford by the well-known classical tutor J. Y. Sargent, who had examined at Merchant Taylors'. In his first year he won two university classical prizes, the Hertford and the Ireland—the former open to first- and second-year students, the latter to all years—as well as scoring forty runs in the freshmen's cricket match. He proceeded to gain first classes in both classical moderations (1885) and literae humaniores (1888), and to gain three more prizes for composition and the Craven scholarship (1886). His precocious gifts led to friendship with several Oxford scholars, including three eccentrics: Thomas Snow (his college tutor), Robinson Ellis, and David Margoliouth. He was also befriended by Arthur Sidgwick of Corpus Christi College, whose liberalism and instinctive feeling for Greek resonated with Murray's talents and assumptions.

By the end of his student career Murray had already become involved in political debate, and had spoken several times at the Oxford Union. His support of home rule for Ireland was predictable but placed him in a small minority. His allegiance to Mill was tested, but not broken, by the idealist critiques developed in Oxford. Religion, too, was explored, and the agnostic Murray formed a friendship with the Anglican Charles Gore, then head of Pusey House. Several colleges offered him fellowships, and in 1888 he chose New College (taking an examination which the college had offered to waive). By this time he had finished his first work, the utopian adventure Gobi or Shamo; after several rejections, with support from Andrew Lang it was published by Longmans in 1889.

In 1887 Murray met Rosalind Howard, later countess of Carlisle, and with other promising young men was invited to the family home, Castle Howard. Here he met, and promptly fell in love with, his hostess's beautiful eldest daughter Lady Mary Henrietta (d. 1956). At first rejected, he paid court for two years, powerfully supported by Mary's mother, who when her daughter attempted to make conditions, overruled them. The engagement was finally announced in October 1889. By this time Murray was in a position to support a wife, since he had in July been elected to the chair of Greek at Glasgow and could expect an income of £1350 a year. His youth—he was twenty-three—and a lack of evidence of his social standing caused concern among the electors, but were swept aside by glowing academic testimonials and the support of Mary's father (the ninth earl of Carlisle) and James Bryce. The couple were married on 2 December 1889 at Castle Howard by Benjamin Jowett. The arrangements were made by the countess of Carlisle and Murray's mother was in effect excluded from the occasion, which remained a source of bitterness until her death in 1891.

Professor of Greek at Glasgow

At Glasgow Murray entered a teaching environment very different from that of Oxford. He faced large classes (100 was not uncommon) of beginning students, some of them older than their new professor; most of them had never previously encountered Greek, which was compulsory for the general degree. Murray was obliged to collect and bank the student fees which formed part of his professorial income, and to mark large quantities of scripts, though in this he was helped by two assistants. Luckily he discovered a natural authority as a teacher and became a successful lecturer, though he intensely disliked the disciplinary aspects of the role. The contrast was noticed between Murray's unforced eloquence and the plainer style of his predecessor Richard Claverhouse Jebb. In his inaugural lecture Murray followed Jebb in taking a wide view of his subject, declaring that ‘Greece, not Greek, is the real subject of our study. There is more in Hellenism than a language, although that language may be the liveliest and richest ever spoken by man.’

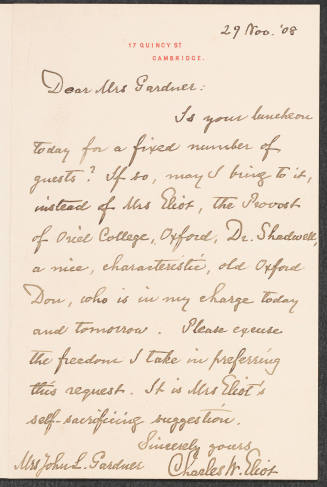

On his appointment Murray became a member of a local élite. He and Lady Mary played their part in social functions, and he made some firm friends, including A. C. Bradley; but their determined liberalism alienated some of his colleagues. In 1889 Murray became a director of the local workers' co-operative, and he and his wife shopped at the local Co-op. In politics he held to a Gladstonian Liberalism, and remained loyal to the teaching of Mill and of his follower John Morley. His public criticism of official policy in the Anglo-Transvaal War placed him in a somewhat beleaguered radical Liberal minority. He also campaigned consistently for teetotalism, a speech to the university's Total Abstinence Society being printed as Claims of Total Abstinence (1894). The Glasgow teaching year ran from November to April, and thus left ample time for writing, though Murray suffered from a series of illnesses, which led in 1892 to his securing a year's leave on medical grounds. Much of this period was spent on what was to be his only return to Australia. In 1893 he circulated other scholars with a proposal for a series of classical texts. This came to nothing, as did a plan to compile an index to Euripides; but his ideas may have influenced D. B. Monro, Ingram Bywater, and Charles Cannan, who were planning what became the Oxford Classical Text series. In 1896 Murray accepted an invitation to contribute a text of Euripides. On all these projects he received much-appreciated advice from the great German Hellenist Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff (1848–1931), to whom he wrote (in Greek) in 1894 after reading the latter's celebrated edition of Euripides' Heracles. Murray sent some of his most promising pupils to Wilamowitz's seminar, the first being Dorothy Murray (no relation) in 1901. The coincidence of name perhaps led to the supposition by his pupil Maurice Bowra and a later regius professor, Hugh Lloyd-Jones, that Murray himself studied under Wilamowitz. The encounter with Wilamowitz, whom he did not in fact meet until the latter's visit to England in 1908, was the most important of Murray's scholarly life: he was exhilarated by Wilamowitz's breadth of scholarship and his concern to bring ancient Greek literature to life, his commitment to the staging of his own translations of Greek drama, and his love (which Murray shared) of the plays of Ibsen. As Murray said in his presidential address to the Classical Association in 1918, ‘The Scholar ... must so understand as to relive’.

The other major product of Murray's time in Glasgow was his History of Ancient Greek Literature (1897), based on his student lectures. The book is eloquent, but though enthusiastically reviewed by his friend Verrall, had a mixed reception among classical scholars. In his preface Murray wrote that ‘to read and re-read the scanty remains now left to us of ancient Greek literature is a pleasant and not a laborious task’; the Cambridge Greek scholar Henry Jackson wrote in his copy, ‘Insolent puppy’. The major weakness of the book was that it fell between two stools, the short inspirational essay and the longer, more comprehensive account. Nevertheless it was several times reprinted.

In 1897 Murray was urged by his doctor to resign his chair on the ground of ill health, and in 1899 finally did so. One of his medical advisers encouraged him to apply for a pension under a contractual clause relating to permanent incapacity; but he later became reluctant to sign a certificate, and Murray withdrew his application. The Murrays, with their children Rosalind (b. 1890), Denis (b. 1892), and Agnes (b. 1894), moved to Churt in Surrey, to a house bought for them by Lady Carlisle. It was on her financial support that Murray now relied until 1905. The nature of his illness is unclear, but it is likely that both physical and psychosomatic illness played a part. An additional factor was the health of their daughter Rosalind: she had had diphtheria and pneumonia and was, Murray claimed, ‘absolutely forbidden to live in Glasgow or anywhere near’ (letter to David Murray, 31 March 1899, U. Glas., Archives and Business Records Centre, Mu.22–f.7 [10]). Rosalind was eventually dispatched abroad in the care of companions, and did not emerge into ordinary society until she was eighteen. In these early years the Murrays' marriage was not always harmonious. As well as concerns about their own and their children's health, they had clashes of temperament to deal with, and serious quarrels can be detected in their correspondence, even where it was later weeded by their daughter Rosalind and by Murray's secretary Jean Smith to remove evidence of disagreement.

While at Churt Murray began working on Euripides for the Oxford Classical Text series; his text appeared in three volumes in 1902, 1904, and 1909. For the first volume he relied heavily on material sent by Wilamowitz, but in 1901 he travelled to Paris, and in 1903 to Florence and Rome, to inspect manuscripts of the plays. The volumes were several times reprinted and enjoyed a long life, being replaced only by the text of James Diggle (1981, 1984, 1994). In his preface the new editor praised Murray's sober judgement, though he was less impressed by his care in collating manuscripts. Murray himself wrote to Bertrand Russell on 7 May 1901 that ‘It is like laboriously cleaning a very beautiful statue’ (Bodl. Oxf., MS G. Murray 165.13); in 1908, in the final stages of the project, he called it a ‘disgusting task’ (West, 118). This may explain why in 1906 Murray refused an invitation from Oxford University Press to produce an Oxford Classical Text edition of Sophocles; a task which he unsuccessfully urged on Wilamowitz in the following year. But it was in any case not Sophocles but Euripides, with his psychological insight, rationalism, and scepticism—not least towards established religion—who attracted Murray.

The other major task Murray worked on at Churt was a series of translations of Euripides and Aristophanes. Published from 1902 onwards, they were widely performed on stage, and made Murray's name in theatrical circles. They were also taken up by amateurs, including working-class groups. Murray gave readings from them in schools, universities, and elsewhere, impressing his audiences with his beautiful voice. Even in his late eighties his voice retained much of its beauty: in a review of Wilson's Murray Peter Levi described it as ‘preposterously golden’ (The Independent, 28 Jan 1988). It later became fashionable (a fashion led by T. S. Eliot) to decry the style of the translations as a too-faithful echo of Swinburne and Morris. Their original auditors, however, must have found in them a clarity and eloquence missing from the stilted language of many contemporary translations from Greek literature. Murray's reading of the Hippolytus at Cambridge in 1902 brought praise from Bertrand Russell, a cousin of Lady Mary's, to whom he became very close. He also met Rudyard Kipling, but while admiring his work he was repelled by him.

Murray's involvement with the theatre went well beyond these translations. During his recuperative sea journey in 1892–3 he had begun a play, Carlyon Sahib, a rather grim utopian tale set in India. Its production in 1899 was not a success, but by this time Murray had come into contact with leading members of the theatrical world, notably the critic William Archer, the actor–manager Harley Granville Barker, and the playwright and critic George Bernard Shaw. Of these the first became a firm friend, the second produced plays for Murray, and the last caricatured him, his wife, and his mother-in-law in Major Barbara (1905): Murray's character Adolphus Cusins was played by Barker. Archer advised Murray on his second play, Andromache, an attempt to write a tragedy for modern times. It was produced in 1901 but failed, though it impressed some severe critics, including Shaw and A. E. Housman. The philosopher Henry Sidgwick found it ‘very spirited and excellent reading: but it seemed to me that between deliberate erudite barbarism and spontaneous natural modernity what we used to call the “Hellenic spirit” has somehow slipped through’ (Sidgwick to H. G. Dakyns, 7 May 1900, Schultz collection, Newnham College, Cambridge). Murray's venture into theatrical life brought him into contact with several leading ladies, and led to quarrels with Lady Mary. In 1908 he admitted to her that ‘I do become charmed by a certain kind of beauty ... these rather emotional friendships do come drifting across my heart’ (Wilson, 144), but reaffirmed his love for her, while insisting on the right to act according to his own judgement.

Murray also made academic friends in this period, including the Cambridge classical scholars Arthur Verrall and his friend Jane Harrison. In both cases their styles of work resonated powerfully but only partially with his own. Verrall, whom he had met in Switzerland in 1894, was an eloquent re-creator of Euripidean drama with a strong theatrical sense, but his interpretations were vitiated by rationalist fantasy. Some of the emendations he offered of Euripides' text Murray described as ‘subtle and attractive’, but treated with caution. Harrison was the moving spirit of what has been called Cambridge ritualism: the reinterpretation of Greek tragedy as a product of ritual practices [see Cambridge ritualists]. She, Murray, and her protégé Francis Cornford exchanged ideas about the new potential of anthropology for the analysis of Greek literature and religion, and (unusually for the time) contributed to each other's books. Thus Harrison's Themis: a Study of the Social Origins of Greek Religion (1912), which was dedicated to Murray, included his ‘Excursus on the ritual forms preserved in Greek tragedy’. Murray, however, always remained unwilling to abandon his vision of a liberal and progressive Hellenism for Harrison's focus on primitive origins and chthonic religion. He recognized that each generation had constructed its own picture of Greece—the ‘serene classical Greek’ of Winckelmann was a phantom—but, while acknowledging that ‘there is more flesh and blood in the Greek of the anthropologist’, insisted that ‘he is ... a Hellene ... without the spiritual life, without the Hellenism’ (Murray, A History of Greek Literature, 1897, xv).

Professor of Greek at Oxford

In 1905 the family moved to Oxford, after Murray accepted an offer of a fellowship at New College. At Oxford he found several talented undergraduates, including J. D. Denniston and Arnold Joseph Toynbee, later to become his son-in-law. In 1908 Murray was appointed regius professor of Greek in succession to Ingram Bywater; he had been dubious of his fitness for the post, and was ready to work with another candidate, the Scottish Hellenist John Burnet. In the same year Wilamowitz visited Oxford, giving two addresses in translations made by Murray; and in his inaugural lecture at Oxford Murray quoted Wilamowitz's declaration that ‘ghosts will not speak till they have drunk blood; and we must give them the blood of our hearts’, pleading for a revivifying of Greek studies. To this end he urged a reconstruction of the Oxford classical course to make it more integrated, wider in scope, and less mechanical in its training. For much of his time there, until he retired in 1936, Murray worked to broaden what he saw as an unduly limited and unintegrated Greats curriculum of history and philosophy: literature hardly figured, being largely confined to the first half of the preliminary (moderations) course, and the subjects which did were rarely placed within a wider context. To remedy this he organized a series of lectures prefatory to the course; these came to be known as the ‘Seven against Greats’ (a reference to Aeschylus's Seven Against Thebes, in which a band of heroes attacks the seven-gated city). The metaphor was apt for a challenge mounted from without to a system of teaching dominated not by professors, but by college tutors. Murray himself was never a ‘college man’, though he proved a staunch supporter of Somerville College until his death.

The most contentious issue Murray faced on taking up his chair, however, was that of compulsory Greek—a requirement made by Oxford (and Cambridge) of all students. The debate on whether it should be maintained, which had begun in 1870, had flared up recently, and Murray, with some heart-searching, adhered to his commitment to ‘Greece, not Greek’. He became a leading spokesman for the abolition of the requirement by the university, making a number of enemies in the process. In 1909–10 he pressed a compromise position which was rejected. The issue was raised again after the First World War, and compulsory Greek was finally abolished in March 1920. By this time Murray was an influential member of the prime minister's committee on the position of classics in the educational system, appointed in 1919. In its report, published in 1921 and in part written by Murray, the committee concluded that while the position of Latin was fairly secure, Greek was in a precarious position, being taught to under 5 per cent of secondary school pupils.

At Glasgow Murray had considered a political career, but after his resignation resolved to devote himself to Greek literature, and refused several invitations to stand for parliament. Nevertheless he continued to speak in public about causes dear to his heart, including women's suffrage (he supported the suffragists but not the suffragettes). An important educational initiative in which Murray was involved for the rest of his life began when he agreed to act as general editor of the Home University Library in 1911. This series of short books, written by experts in an accessible style and aimed at the intelligent reading public, proved very popular; by the end of 1913 over a million had been sold. Murray's own contribution was Euripides and his Age (1913). In it he presented the poet as a radical and freethinker; the book belonged to a contemporary revaluation of a dramatist whom the Victorians had regarded as inferior to Aeschylus and, especially, Sophocles. If this was his best-known book, perhaps his best was The Rise of the Greek Epic (1907), based on a series of lectures at Harvard. In it Murray attempted to mediate between unitarian (single-author) and analytical (multipe-author or disintegrationist) views of the Homeric poems by seeing them as the products of a coherent tradition which moved steadily towards the expurgation of cruder elements in favour of a higher humanity. (In an appendix he discussed the possibility that some passages in the version handed down had been affected by bowdlerization.)

Another American lecture series, at Columbia in 1912, produced Murray's Four Stages of Greek Religion (1912). Here he again argued for a progressive Hellenism, highlighting the virtues of fifth-century Athens and reacting against the primitivist emphases of Jane Harrison. The book revealed its author to be a reverently agnostic rationalist with a maturing scepticism about religion.

International relations and Liberalism

After the outbreak of war in 1914 Murray became increasingly involved in government activities, his initial doubts about Britain's declaration of war having been overcome by Sir Edward Grey's speech to the House of Commons on 3 August 1914. He wrote several pamphlets for the bureau of information, including The Foreign Policy of Sir Edward Grey (1915), and made lecture tours of Sweden and the USA. In 1917, despite the rise to power of Lloyd George, whose policies he detested, Murray became a civil servant and worked part-time for the Board of Education, whose president was his friend H. A. L. Fisher. He used his position to help those imprisoned as conscientious objectors, notably Bertrand Russell. Throughout the war Murray was involved in discussions about international peace, some of them within the League of Nations Society (1915), whose vice-president he became in 1916. In 1919 he was persuaded to stand as a Liberal parliamentary candidate for Oxford University; he did not campaign and barely saved his deposit.

By this time Murray was working for the League of Nations Union (1918), and on the foundation of the League of Nations itself in 1920 he began a long association which lasted until the Second World War, working with his friend Robert Cecil. In 1921 he attended the league's assembly by arrangement with his friend Jan Smuts, to whom he remarked on the ‘rather large proportion of small dark Latin nations’ (Murray to Smuts, 8 Oct 1921; Murray, 185). He joined the league's committee of intellectual co-operation on its foundation in 1922 and succeeded Cecil as its chairman in 1928. Between the wars Murray was tireless in chairing international meetings, mediating, conciliating, and smoothing over differences. A proposal by George V to offer him membership of the Order of Merit in 1921 was blocked by Lloyd George; he was eventually appointed in 1941. (He had refused offers of knighthood in 1912 and 1917.) His name had also been on the list of the peerages that the Liberal government was contemplating creating if a forced creation became necessary in 1910 to get its budget through the House of Lords.

All this outside activity inevitably curtailed the time Murray spent on his university duties, and in 1923 the vice-chancellor, Lewis Farnell, asked Murray if his League of Nations Union duties were compatible with retaining his chair; Murray responded by offering up to half his salary to fund a readership in Greek. This was subsequently filled by Edgar Lobel. It was for Murray's efforts in the field of international relations that he became best-known, and he was a powerful inter-war Liberal presence; his stature was such that in 1929 Ramsay MacDonald's government considered asking him to become ambassador in Washington. Yet he was never an ordinary Liberal: his mind has been described as ‘freakishly individual’, and some found him ‘oppressively virtuous and intellectual’ (Bentley, 171). After his defeat in 1918 he stood unsuccessfully as candidate for the Oxford University parliamentary seat on five further occasions (1919, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1929). His political choices had in some ways led him into the wilderness. Like other Liberals, he had been sidelined by the growth of the Labour Party, and in Oxford his commitment to Asquith had distanced him politically from Herbert Fisher, who supported Lloyd George. Murray's drift away from party politics led him in the 1930s to a dead-end destination: the well-intentioned but bloodless Next Five Years Group, whose manifesto he signed in 1935.

The Murrays had moved in 1919 to their final home, Yatscombe on Boars Hill outside Oxford; after 1921 their finances were bolstered by inheritances from the earl and countess of Carlisle. They had difficulties with their two youngest children, Basil (b. 1902) and Stephen (b. 1908), and the health of the eldest son, Denis, had never recovered from his internment during the war. Denis died prematurely in 1930, Basil in 1937. The most serious blow, however, was the death of their daughter Agnes from peritonitis in 1922. This may have deepened Murray's involvement in the Society for Psychical Research, of which he had been president in 1916. He had taken part in psychic séances since the turn of the century and was regarded as having strong telepathic powers. Changes in relations within the family were manifested in part in religious commitments. In 1925 Lady Mary joined the Quakers, for whom she worked devotedly. Rosalind converted to Catholicism in 1933, and in 1939 published The Good Pagan's Failure, an anti-rationalist manifesto containing thinly veiled criticism of both her parents.

In the 1930s Murray played a major part in efforts to relocate and employ German refugee scholars. His collaboration with William Beveridge of the London School of Economics led to the foundation in 1934 of the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning, in which he worked with the Aristotelian scholar David Ross and with Walter Adams. One of the most notable refugee scholars brought to Oxford was Eduard Fraenkel, who was in 1935 elected to the Corpus chair of Latin. Fraenkel played a large part in advising Murray on the Oxford Classical Text edition of Aeschylus, to the point where Murray became tired of his somewhat peremptory admonitions. Advice was also forthcoming from Ludwig Radermacher of Vienna and from Denys Page. The resulting text, which appeared in 1937, was not well received, and has indeed been described as perverse and eccentric (Lloyd-Jones, 209). It is perhaps significant that in the lengthy discussion of his predecessors in his massive edition of the Agamemnon (1950), Fraenkel makes no mention of Murray. Murray in turn found Fraenkel's edition Germanic, lacking in taste despite all its learning: a judgment which echoed the contrast he had made during the First World War between English sensitivity to style and Teutonic systematic learning (‘German scholarship’, Quarterly Review, 223, 1915, 330–39). A later revision (1955), accomplished with the help of Eric Dodds, Edgar Lobel, and Paul Maas, suffered from a failure to take adequate account of the work of the Polish scholar Aleksander Turyn on the manuscript tradition of Aeschylus. It was sharply criticized after Murray's death by a combative young Cambridge scholar, who quoted the remark of the car designer Alec Issigonis that a camel was a horse designed by a committee (R. D. Dawe, The Collation and Investigation of Manuscripts of Aeschylus, 1964, 9–10). The replacement Oxford Classical Text, edited by Denys Page (1972), makes no mention of Murray's text—another significant silence. A general book on Aristophanes (Aristophanes, 1933) also received little critical acclaim. It was not a major work of scholarship, and the preface opens with the statement: ‘There is little or no research in this book’; but it includes a notable discussion of the poet's skill as a parodist.

Murray's retirement from his chair in 1936 was marked by two collaborative volumes reflecting the breadth of his work: Greek Poetry, a set of academic essays, and Essays in Honour of Gilbert Murray, a wide-ranging tribute by eighteen friends. The appointment to the regius chair was in practice made by the prime minister, and Murray approached Stanley Baldwin with suggestions. The Oxford candidates were the learned but dry John Denniston and Maurice Bowra, whose scholarship Murray thought lacking in ‘quality, precision and reality’ (Murray to Baldwin, 2 June 1936 Bodl. Oxf., MSS G. Murray 77.138–40). His preferred candidate was Eric Dodds—also admired by Fraenkel—who was duly appointed to succeed him. Murray's intervention was unwise, breaking as it did the convention that one should not influence the appointment of a successor, and caused some scandal in Oxford; but in the event Dodds proved a worthy holder of the chair.

The League of Nations remained a major preoccupation for Murray after his retirement, but its fortunes declined after its failure to prevent or end the Ethiopian war of 1935–6. Murray later declared that he and his colleagues had overestimated the reasoning powers of the masses and underestimated the strength of nationalism; nor had they realized that the league could not function properly unless the USA joined it. His continuing commitment to the league's ideals was reflected in his being elected president of the United Nations Association three times after the Second World War. Yet he became in this period increasingly conservative in his views. In 1950 he voted Conservative; in 1955 he was pleased with the Conservative election victory, and remarked that ‘nearly all the educated people I meet are Liberal, but vote Conservative’ (Wilson, 391). In 1956, to the surprise and alarm of some fellow Liberals, he supported the Anglo-French military action in Suez, regarding Nasser's nationalization of the canal as a barbaric encroachment on the civilized world. Within the United Nations Murray felt that ‘We lie at the mercy of a mass of little barbarous nations, intoxicated with their own nationality who constitute a great majority of the Assembly’ (ibid., 392).

Death and reputation

From 1952 onwards Lady Mary was unable to cope with ordinary social life. Her death in September 1956 was a heavy blow for Murray, who became noticeably more frail. He himself died at Yatscombe on 20 May 1957 and was, according to his wishes, cremated. His final days gave rise to a controversy which was magnified by the religious divisions between his children. Shortly before his death he was visited by a Roman Catholic priest, but it remains unclear whether any rites were administered or, if so, whether Murray was capable of requesting or understanding them. A newspaper interview given by his (Catholic) daughter Rosalind led to a bitter argument within the family, and to public protests against his interment in Westminster Abbey, which nevertheless took place there, at the request of the United Nations Association, on 5 July 1957.

Murray's reputation as a scholar has suffered posthumously. Like his friend and fellow Hellenist J. W. Mackail, as a young man he abandoned plans to go to Germany to learn the methods of systematic research which were so highly developed there. Though his mastery of Greek gave him great insight into ancient texts, examining the minutiae of their transmission was not his forte, and in this area he remained a gentleman amateur. It is remarkable by modern standards that though regius professor of Greek for twenty-eight years, Murray published only a handful of articles in classical journals: indeed he once expressed a ‘physical abhorrence for writing in periodicals’ (West, 119). Nor did he produce commentaries on ancient texts, like his predecessor and successor in the Oxford chair. His interest

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Fockbury, England, 1859 - 1936, Cambridge, England

Edinburgh, 1860 - 1920, Cintra, Portugal

founded Edinburgh, 1795

Boston, 1834 - 1926, Mount Desert, Maine

Rome, 1834 - 1903, Saint Leonards, England