Charles Wyndham

Liverpool, 1837 - 1919, London

Charles Culverwell's education, like much of his life, was cosmopolitan. He went to boarding-schools in England, Scotland (where he took part in amateur theatricals at St Andrews), Germany, and France. In Paris he frequented the Comédie-Française and the Palais Royal: the acting styles of each inspired his future mastery of high comedy and farce, and the Palais Royal supplied much of his repertory, ‘Englished’ in adaptation. His father sent him to King's College, London, to read medicine; but the student spent all available time acting at a tiny amateur house near King's Cross and theatre-going in the West End, where first he saw the light comedian Charles James Mathews, whose style of performance was to prove as strong an influence as the Parisians. None the less he became a licentiate in midwifery and MRCS (1857), and, after experience at hospitals in Ireland and Germany, a licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries and MD in the University of Giessen (1859). Uniquely, at Charing Cross Hospital in 1903, he addressed a roomful of medical students in the dual capacity of actor and doctor; but there is no public evidence of his having employed his medical skills after 1865, and by 1883 his name had disappeared from the medical registers.

The practice of Dr Charles Culverwell, which was set up at 3 Great Marlborough Street, London, failed. It was on 30 November 1860—when appearing as Captain Hawksley in an amateur performance of Tom Taylor's Still Waters Run Deep at the Royalty Theatre, Soho—that he first used the name Wyndham. The choice was apparently random, but was retained as his stage name ever after, and was ratified for all purposes by deed poll on 8 October 1886. As Charles Wyndham (and from 1902 Sir Charles) he worked his peculiar magic upon audiences in North America, Germany, Russia, and the West End of London, beguiling them with a rare and practised skill. He was tall, straight, and slender, with broad shoulders and long legs. In his youth his voice was harsh and inflexible, which for years he tried to conceal by speaking fast. His quickfire delivery and rugged good looks qualified him until middle age for the dashing young hero of Victorian farce. Then, in the final decade of the nineteenth century, when he switched to the more measured elder statesmen of Henry Arthur Jones's ‘society dramas’, he grew more attractive still. A slightly crooked mouth and heavy eyelids lent him a quizzical or mystified look that only enhanced his appeal. As his wavy hair turned from brown to silver his charisma increased. Seldom in fifty years on the stage did he fail to capture the men's admiration or the women's hearts. With the sole exception of Ellen Terry, no British player of his era surpassed his ability to sway the audience by the power of personal charm. Appropriately, the first time he used his new name he played a seducer.

On 8 February 1862 Wyndham turned professional actor, reappearing at the Royalty in the title character of an anonymous trifle, Christopher of Carnation Cottage. That same year he sailed for America, enlisted in the Federal army as a medical officer, and served almost to the end of the civil war. Acting Assistant Surgeon Culverwell was close to the horrors of battle. Scarcely ever would he speak of them; their effect upon him was evident, long after, in his determined support of British disabled servicemen by means of charity performances at his own theatres during the South African War and the First World War.

Wyndham's American début was made on 14 April 1863 at Grover's Theatre, Washington, as Osric to the Hamlet of John Wilkes Booth, who in 1865 assassinated President Lincoln. He landed the job by brandishing notices of his London performances without saying he had written them himself. For most of the rest of the war he alternated stage costume and uniform, and suffered in each. More than one theatre manager dismissed him for incompetence; but, undaunted, he set his sights in earnest on the English stage, and returned to London and to the wife he had left behind. Five years had passed since his marriage to Emma Silberrad (c.1837–1916) at the parish church of St Matthew, Brixton, on 27 June 1860. A merchant's child, but also a moneyed German aristocrat, she was the granddaughter of a prince of the Holy Roman empire, Baron Silberrad of Hesse. By marrying into this house of merchant princes Wyndham was spared the fear of destitution that plagued other actors.

In the autumn of 1866, having returned to the Royalty, Wyndham danced as well as acted himself into favour as Hatchett in F. C. Burnand's burlesque of Douglas Jerrold's Black-Eyed Susan. Other London engagements followed, most notably (in 1867–8) the inaugural season at the Queen's Theatre, Long Acre, with Ellen Terry, Henry Irving, and J. L. Toole. There he repeated the seducer Hawksley. London had been reached without hard apprenticeship in the stock companies of provincial towns, but it was not all advantageous. Wyndham lacked repertory experience, and hence versatility—as he found when attempting the part of Cyrano de Bergerac (in an adaptation of Rostand's play of that name) at Wyndham's Theatre on 19 April 1900. He was in his element, though, when acting in rattling and often risqué farces—such as Clement Scott's The Great Divorce Case (15 April 1876), James Albery's The Pink Dominoes (31 March 1877), and W. S. Gilbert's Foggerty's Fairy (15 December 1881)—especially when at the Criterion, an intimate basement theatre at Piccadilly Circus where he presided, first as co-manager, then in sole charge, from 1875 to 1899, and where he continued to have a decisive interest until his death. In ‘Criterion farce’, translated from French originals with names and places Anglicized, faithless husbands and suitors were seen in the most favourable light. Men in the audience smirked approvingly, and women swooned. No one was ever more able than Wyndham to commend the transgressor. He moved about the stage with perfect ease; every gesture had been rehearsed in a mirror, and to ensure a fluid use of the hands he never carried a stick. His wonderful naturalness was his greatest legacy to the next generation of actors.

Costume pieces overtook farces at the Criterion, and for six years Wyndham concentrated on showing off his legs in tight breeches. T. W. Robertson's David Garrick (in which he played Garrick, 13 November 1886), Boucicault's London Assurance (as Dazzle, 27 November 1890), and eighteenth-century comedies by Goldsmith, Sheridan, and O'Keeffe were produced. David Garrick became his chief piece; but many thought his finest achievement of all was the portrayal of mellow, titled men of the world, cynical but tender, in the plays that Jones moulded for him—Viscount Clivebrook in The Bauble Shop (26 January 1893), Sir Richard Kato QC in The Case of Rebellious Susan (3 October 1894), Dr Carey in The Physician (25 March 1897), Colonel Sir Christopher Deering in The Liars (6 October 1897), all at the Criterion, and Sir Daniel Carteret in Mrs Dane's Defence (9 October 1900) at Wyndham's. Charles Haddon Chambers's The Tyranny of Tears (6 April 1899) and H. H. Davies's The Mollusc (7 October 1907), both at the Criterion, were among other plays that exploited his charm. Wyndham's appeal to women of all ages was immense. His voice, when excited, had a catch in it, which men thought rasping. To women it was a caress. Wyndham in his sixties, on the stage at least, was the sort of man women liked to be scolded by.

From the Criterion's profits Wyndham built Wyndham's Theatre in 1899 and the New Theatre (later renamed the Albery) in 1903, in both of which he had a managerial share to the end of his life. His was a record of continuous and simultaneous West End management that probably no actor will equal. As a manager he was indefatigable. He pioneered the ‘flying matinée’—an out-of-town performance by a company playing the same evening in London. Between 1874 and 1878 he produced numerous plays for matinées at the Crystal Palace, Sydenham, using actors who were occupied in the West End. Earlier still, in 1870, he had formed the Wyndham Comedy Company and toured the American midwest for three years with a largely Robertsonian repertory; but an American farce, Bronson Howard's Saratoga (with Wyndham perpetually poised on the brink of matrimony with one girl or another), went down better. Having bought the British rights, he commissioned an adaptation, and on 24 May 1874 starred at London's Court Theatre in Brighton, the Anglicized version. It became Wyndham's standby. His Criterion company was in 1882–3 the first English troupe ever to reach America's west coast. He took them to the United States three more times between 1889 and 1910. In 1887 and 1888 he acted Garrick in German (his own translation), first in Silesia and Berlin, then at St Petersburg before Tsar Alexander III and the tsarina. For an English actor–manager of those days Wyndham's international experiences were exceptionally long and diverse.

From 1905 to 1919 Wyndham served as president of the Actors' Benevolent Fund. He excelled at after-dinner speaking, and belonged to the Garrick, Savage, Beefsteak, Eccentric, and Green Room clubs, though seldom went. He also joined the Players' Club of New York. Only on the stage, however, could he relax. Keeping fit with long walks, he got away with playing Young Marlow in Goldsmith's She Stoops to Conquer at the age of fifty-three and the scarcely less youthful Charles Surface in Sheridan's The School for Scandal at sixty-nine; but by the time of his final appearance, as Garrick at the New Theatre on 16 December 1913, he had long suffered from aphasia, which severely affected his work, and may explain the absence (unusual for an actor–manager) of an autobiography. Occasional outbursts against subordinates, including women, belied his reputation for gallantry.

Wyndham's wife, from whom he separated in 1897, died in January 1916. On 1 March of the same year, at Chertsey register office, Surrey, he married Mary Charlotte Moore (1861–1931), the daughter of Charles Moore, a parliamentary agent, and for a quarter of a century the widow of the dramatist James Albery. She was twenty-four years his junior. An entrancing actress of comedy, she had become his leading lady in 1885, his mistress soon after, and in 1896 his business partner. Wyndham, suffering from pneumonia and senility, died on 12 January 1919 at their home, 43 York Terrace, Regent's Park, London, survived by her and a son (Howard Wyndham, who was also a theatre manager) and daughter from his first marriage. He was buried on 16 January at Hampstead cemetery, and left a fortune of nearly £200,000.

Both Wilde and Shaw thought Wyndham the ideal comedy actor. His stage persona was the model for John Worthing in Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest and the young heroes of Shaw's The Philanderer, Arms and the Man, Candida, and You Never Can Tell. He was then nearing sixty. Those plays were offered to Wyndham in preference to other managers—with the exception of The Importance of Being Earnest, which was dangled first before Charles Hawtrey, who could not afford it. Wyndham instantly snapped it up, but later, thinking his schedule was full, gave it to George Alexander. Had he ever produced plays of Wilde's or Shaw's, with himself in the parts conceived for him, Sir Charles Wyndham might have figured more considerably in the development of drama. As it was, he left other monuments: Wyndham's Theatre, and the establishment of English farce in a full-length form.

Michael Read

Sources

W. Trewin, All on stage: Charles Wyndham and the Alberys (1980) · Lady Wyndham [M. Moore], Charles Wyndham and Mary Moore (privately printed, Edinburgh, 1925) · T. E. Pemberton, Sir Charles Wyndham (1904) · F. T. Shore, Sir Charles Wyndham (1908) · W. L. Courtney, ‘Sir Charles Wyndham: an appreciation’, Daily Telegraph (15 Jan 1919) · G. Rowell, ‘Wyndham of Wyndham's’, The theatrical manager in England and America: player of a perilous game, ed. J. W. Donohue, jun. (1971), 189–213 · G. Rowell, ‘Criteria for comedy: Charles Wyndham at the Criterion Theatre’, British theatre in the 1890s: essays on drama and the stage, ed. R. Foulkes (1992), 24–37 · Daily Telegraph (13 Jan 1919) · The Era (15 Jan 1919) · Manchester Guardian (13 Jan 1919) · Morning Post (13 Jan 1919) · The Times (13 Jan 1919) · J. M. Bulloch, ‘Sir Charles Wyndham's family, the Culverwells’, N&Q, 168 (1935), 290–94

Archives

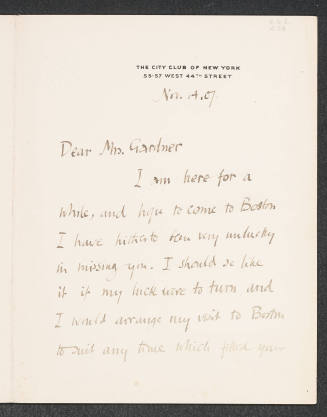

BL, letters to George Bernard Shaw, Add. MS 50553 · U. Nott. L., letters to Lady Galway

FILM

BFINA, performance footage

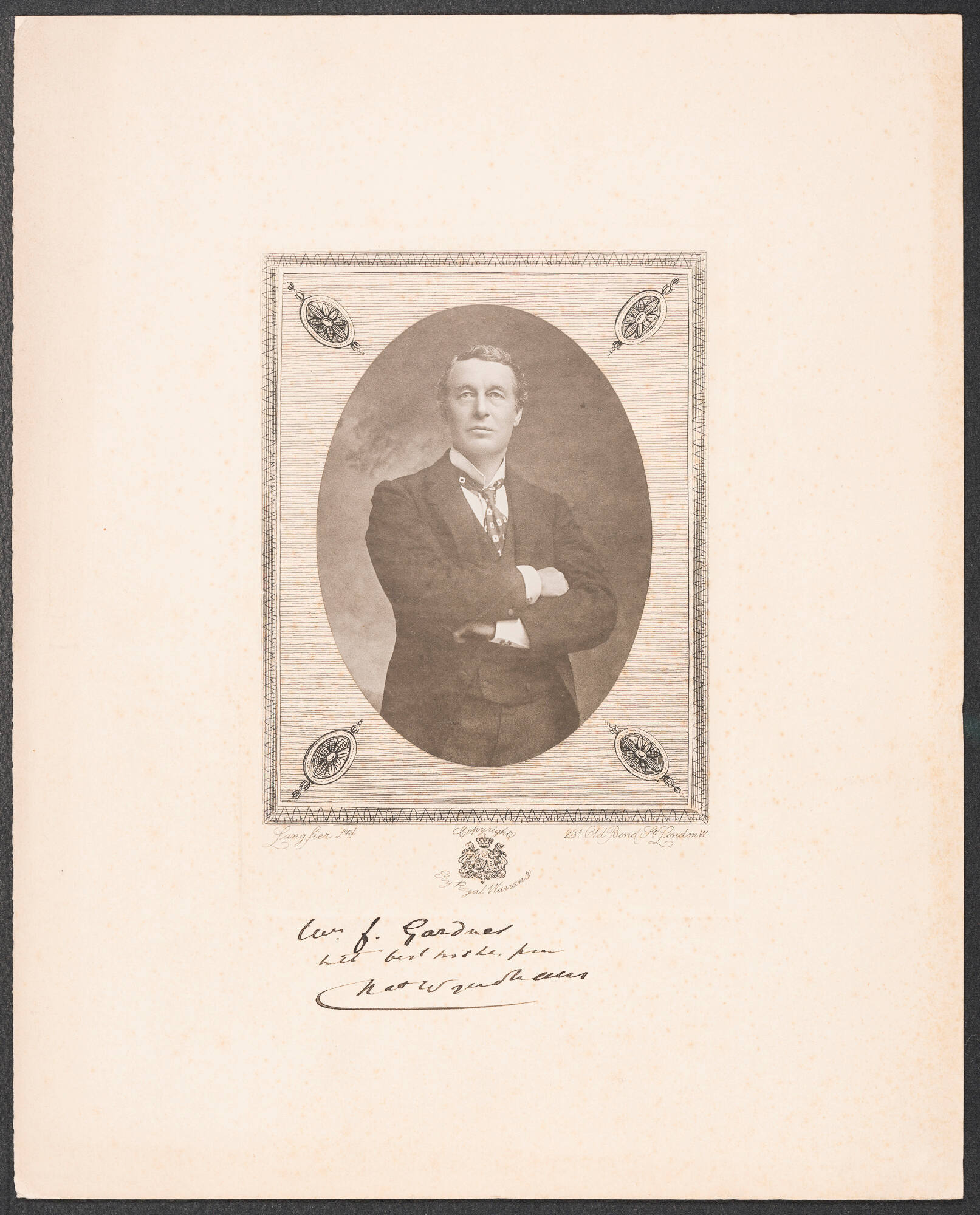

Likenesses

Barraud, cabinet photographs, 1888, NPG · Barraud, carte-de-visite, 1888, NPG · J. Pettie, oils, exh. RA 1888 (as David Garrick), Garr. Club · H. Furniss, caricature, pen-and-ink drawing, c.1905, NPG · Ash, caricature, mechanical reproduction, NPG; repro. in VF · Barraud, photograph, NPG; repro. in Men and Women of the Day, 2 (1889) · M. Beerbohm, caricature, drawing, V&A · M. Beerbohm, caricature, drawing, U. Texas · L. Bertin, woodburytype photograph, NPG · S. P. Hall, pencil sketch, NPG · Langfier, cabinet photograph, NPG [see illus.] · photogravure photographs, NPG

Wealth at death

£197,035 14s. 11d.: probate, 4 April 1919, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Michael Read, ‘Wyndham, Sir Charles (1837–1919)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/37051, accessed 6 Aug 2013]

Sir Charles Wyndham (1837–1919): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/37051

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Coventry, England, 1847 - 1928, Tenterden, England

Keinton Mandeville, England, 1838 - 1905, Bradford, England

Saxmundham, England, 1843 - 1926, Sissinghurst, England