Wilfrid Philip Ward

Ware, England, 1856 - 1916, London

The three great Victorian archbishops of Westminster, Nicholas Wiseman, Henry Edward Manning, and Herbert Vaughan, loomed large in Ward's childhood. According to family legend, Wiseman placed his biretta on the boy's head and told him ‘You will be a Cardinal’ (Ward, The Wilfrid Wards, 1.20), but the great unseen influence upon him, the ghost at this cardinalitial banquet, was that of John Henry Newman, whose University Sermons had formed his father's philosophy, but who had become a lost leader to the Wards by distancing himself from the new nineteenth-century trend towards ultramontanism.

Ward was sent to school at Downside Abbey, near Bath, in 1868–9, and then returned to St Edmund's, near Ware. His father encouraged his interest in Newman's philosophy of religion, and he took the external University of London BA (matriculated 1872, graduated 1876). He was enrolled in 1874 as a student at Manning's ill-fated Catholic University in Kensington, where he profited from the expert philosophical instruction of Father Robert Francis Clarke, though he later regretted his father's refusal, on religious grounds, to send him to his own alma mater, the University of Oxford. In 1877, on Vaughan's advice, he tried his vocation to the priesthood at the English College, Rome. He was touched there by romanità, the spirit of Roman Christianity, and enjoyed being organist in the college chapel, but was dissatisfied by his Roman philosophical teaching as simply relying on past authority. In 1878 ill health forced him to leave Rome for the seminary of Ushaw College in co. Durham, where he was choirmaster and wrote the music for an operetta, The Gambler of Metz. Bishops Vaughan and Ullathorne confirmed his growing sense that he had no clerical vocation, so he abandoned the idea of ordination and left Ushaw in 1881.

Ward half-heartedly entered at the Inner Temple, London, to become a barrister, while the contempt of one of his sisters (he did not record which one) and fear of his father's anger strangled at birth his fleeting impulse to become an opera singer. He began to see his vocation as one to advance English Catholic intellectual life, but recognized that there was no official encouragement or structure for such a career outside the priesthood. His only academic positions were to be as examiner in mental and moral philosophy for the Royal University of Ireland (1890) and a member of the royal commission on Irish university education in 1902. Otherwise his influence was as a freelance scholar and journalist, albeit one with a private income from the sale of the family living. His first essays, inspired by Newman's theory of belief, appeared in The Nineteenth Century (1882–3) and the National Review (1884), and were republished as The Wish to Believe (1885) and The Clothes of Religion (1886). The latter attacked the laissez-faire apologist Herbert Spencer and the positivist Frederic Harrison. His works were praised by William George Ward and by another of Newman's disciples, Richard Holt Hutton, editor of The Spectator, and were commended by Newman himself.

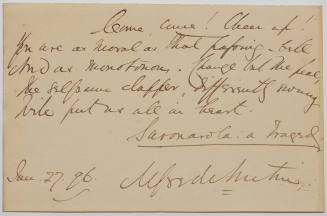

Newman's writings, especially his University Sermons (1843) and Grammar of Assent (1870), helped Ward to absorb and transcend the overwhelming and overbearing legacy of his father. He discharged his filial and intellectual obligations first by editing Ward senior's Essays on the Philosophy of Theism (2 vols., 1884) and then by writing his two-part biography, William George Ward and the Oxford Movement (1889) and William George Ward and the Catholic Revival (1893). These volumes, which reconstructed the Tractarian and Roman Catholic controversies of the early and high Victorian eras, included two essays of particular historical merit: ‘The Oxford school and modern religious thought’ (in the first biography) and ‘The Catholic revival and the new ultramontanism’, written with the help of Friedrich von Hügel (in its sequel). His vivid, penetrating, and affectionate evocation of the formidable, lovable, infuriating, and dogmatic personality of his father has left the elder Ward with a reputation as one of the most colourful characters of the high Victorian era. In addition to applying personal knowledge to historical analysis, Ward's work on his father's biography strengthened or created his ties with his father's friend and neighbour on the Isle of Wight, Lord Tennyson, and with other former members of his father's Metaphysical Society such as Thomas Henry Huxley, Henry Sidgwick, and Frederic Myers. This encouraged him, with the help of A. J. Balfour, Charles Gore, and Edward Talbot, to found in 1896 the Synthetic Society for the learned discussion of religious belief, with a few former surviving Metaphysicals (James Martineau, Hutton, Sidgwick, Myers) as well as some new members (Lord Hugh Cecil, George Wyndham, A. V. Dicey). The membership embraced nonconformists, an Irvingite (Henry Percy, Lord Warkworth), high- and broad-church Anglicans (including Henry Scott Holland and Hastings Rashdall), G. K. Chesterton (before his conversion to Catholicism), and some Catholics, notably the modernists George Tyrrell and von Hügel. The society was dissolved in 1908.

These contacts encouraged Ward in his role as a ‘liaison officer’ (M. Ward, The Wilfrid Wards and the Transition, 1.96) between Catholicism and other religious traditions, and in gathering first-hand historical material on the last generation of eminent Victorians. Ward's marriage on 24 November 1887 to Josephine Mary (1864–1932), the second daughter of James Robert Hope-Scott of Abbotsford (1812–1873) and his second wife, Victoria Howard (1840–1870), herself daughter of the fourteenth duke of Norfolk, brought Ward closer to the fifteenth duke, to whom he became an adviser on theological and ecclesiastical affairs, as over the admission of Catholics to Oxford in 1895, the validity of Anglican orders in 1896, and later the modernist controversy (1907–10). The Wards had five children, one of whom, the precocious Wilfrid Hope Ward (1890–1902), died young; the eldest, Mary Josephine Ward (1889–1975), known as Maisie, was to be a considerable influence on the golden age of English Catholic intellectual life between the wars, and her books about her father remain the best sources for his life.

Ward's interest in ecclesiastical biography was confirmed by his unsuccessful attempt with the duke of Norfolk, Vaughan, and Baron von Hügel to censor or prevent the publication of Edmund Sheridan Purcell's scandalous biography of Henry Edward Manning which appeared in 1895. Yet Purcell's indiscretions had the advantage of leaving no hiding place for ecclesiastical secrets. The truth looked so much more edifying than Purcell's account of Manning's alleged unscrupulous ambition that Ward could be frank when his mentor Herbert Vaughan, by then a cardinal, asked him to write The Life of Cardinal Wiseman (2 vols., 1897). This careful documentary history combined a lively critical narrative of high religious politics with a warm portrait of the most exuberant of the great English ecclesiastics of his generation. It also led to Ward's most ambitious undertaking, a life of his intellectual patron, Cardinal Newman.

Ward's projected biography of Newman had the support of the latter's successor as superior of the Birmingham Oratory, Ignatius Ryder, who had, however, been excluded by Newman from any use of his papers, which were jealously guarded by the cardinal's executor, William Neville. After Neville's death the work began to reach proof stage in 1907, when the fathers of the Birmingham Oratory, who had custody of Newman's correspondence, were appalled to find that Ward thought Newman's philosophy to have been incidentally condemned by Pius X's anti-modernist encyclical Pascendi (1907). Ward was known to be a friend of the Jesuit George Tyrrell, who had appealed to Newman's work to defend himself against accusations of modernist errors. As editor of the Dublin Review from 1906, Ward was vulnerable to criticism from hyper-orthodox Catholics. His friendship with von Hügel, who was equally tarnished with a reputation for modernism, hardly helped him; indeed, the baron's correspondence with other radical scholars was the nearest that Catholic modernism ever came to being a movement, and compromised all his associates. It was at Cardinal Rampolla's insistence that in 1911 Ward withdrew his wholly orthodox epilogue to the Wiseman biography, ‘The exclusive church and the Zeitgeist’, after it had been denounced to Rome. The biography which Ward eventually completed was almost wholly devoted to Newman's life as a Catholic, his forty-four years as an Anglican being dispatched in one chapter of fifty-two pages. In this respect Ward was writing a Roman Catholic ‘Tract for the Times’ on the need for orthodoxy to be self-critical, though this preoccupation hardly appears on the smooth surface of the narrative. Yet Ward was a ‘prodigious blab’ (The Letters and Diaries of John Henry Newman, ed. C. S. Dessain and others, 31 vols., 11–31, 1961–77, 11.xix), ‘vehement, rash and excitable’ (M. Ward, The Wilfrid Wards and the Transition, 1.103), and given to writing angry letters which his wife and daughter tried to stop him from posting. His temperament was not one conducive to mental peace, and in the anti-modernist climate in the church Ward's theological view of a careful, critical, and discriminating, if not a ‘liberal’, Catholicism obscured to hyper-orthodox Catholics the great gulf which lay between him and a modernist like Tyrrell, who denied fundamental credal doctrines. The Oratorians also disliked Ward's stress on the suffering side of Newman's personality, as if he were ‘hyper-sensitive, a souffre-douleur’ in Abbot Butler's phrase (The Letters and Diaries of John Henry Newman, ed. C. S. Dessain and others, 31 vols., 11–31, 1961–77, 11.xx). They also mistrusted the intellectual dialectic of the work, which argued that Newman's Catholicism had dissented strongly from both the liberal Catholicism of Richard Simpson and Sir John Acton and the new ultramontanism of William George Ward and Manning, trying instead to hold the balance between the two schools by combining the critical sense of the one with the orthodoxy of the other. This was, at least in part, a backward projection of Ward's own difficult mediating position between modernists and integralists and, in part, his own final resolution of his father's great battle with Newman, in Newman's favour. After extensive revision, The Life of John Henry Cardinal Newman (2 vols.) appeared in 1912 to critical acclaim, but the Oratorians declined to publish a third volume of letters on the grounds that ‘it would make the letters subordinate to Mr Ward's presentation of Newman’ (The Letters and Diaries of John Henry Newman, ed. C. S. Dessain and others, 31 vols., 11–31, 1961–77, 11.xix).

Ward also edited the 1864 and 1865 editions of Newman's Apologia (1913). According to the later editor of Newman's diaries and correspondence, Charles Stephen Dessain, Ward's ‘best work on Newman’ appeared in his Lowell lectures in America in 1914 (The Letters and Diaries of John Henry Newman, ed. C. S. Dessain and others, 31 vols., 11–31, 1961–77, 31.328). These were edited with his lectures on biography at the Royal Institution (1914–15) as Last Lectures (1918) by his wife, who wrote a long introductory study for them. She also wrote eight novels with religious themes, including One Poor Scruple (1899) and Great Possessions (1909). Ward himself also wrote a study of the Irish Catholic convert poet Aubrey de Vere (1904) and about 250 articles and reviews, some of which were collected and published as books (Witnesses to the Unseen, 1893; Problems and Persons, 1903; Ten Personal Studies, 1908; Men and Matters, 1914). Still valuable as primary sources, mingling personal reminiscence and private knowledge and anecdote with wide reading, their main theme was the enduring value of the great Victorians' contribution to the perception of religious truth.

Ward was a strong conservative who opposed home rule for Ireland, and after 1914 campaigned among Catholic circles for the allied cause. In 1915 he inherited the Isle of Wight family fortune from his eccentric elder brother, Edmund Granville (1853–1915), who had died during the war when property was in the doldrums, and had left several times the value of the estate to the Catholic Church and Catholic education. Ward's humiliation in trying to reach a financial settlement with the church after the long dark night of the modernist controversy made him ill, and he contracted cancer. He died at The Nook, Holford Road, Hampstead Heath, London, on 9 April 1916, and was buried on the family estate at Freshwater on the Isle of Wight. The family estates passed to his elder surviving son, Herbert Joseph Ward (b. 1896).

Sheridan Gilley

Sources

M. Ward, The Wilfrid Wards and the transition, 1 (1934) · M. Ward, The Wilfrid Wards and the transition, 2 (1937) · M. Ward, Unfinished business (1964) · M. J. Weaver, Letters from a ‘modernist’: the letters of George Tyrrell to Wilfrid Ward, 1893–1908 (1981) · M. J. Weaver, ‘A bibliography of the published works of Wilfrid Ward’, Heythrop Journal, 20 (1979), 399–420 · E. Kelly, ‘Newman, Wilfrid Ward, and the modernist crisis’, Thought, 43 (1973), 508–19 · W. J. Schoenl, The intellectual crisis in English Catholicism (1982) · W. Sheed, Frank and Maisie: a memoir with parents (1986) · S. Gilley, ‘Wilfrid Ward and his life of Newman’, Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 29 (1978), 177–93 · S. Gilley, ‘An intellectual discipleship: Newman and the making of Wilfrid Ward’, Louvain Studies, 15 (1990), 318–45 · S. Gilley, ‘New light on an old scandal: Purcell's Life of Cardinal Manning’, Opening the scrolls: essays in Catholic history in honour of Godfrey Anstruther, ed. D. A. Bellenger (1987), 166–98 · W. Ward, William George Ward and the Oxford Movement (1889) · W. Ward, William George Ward and the Catholic revival (1893) · CGPLA Eng. & Wales (1916)

Archives

priv. coll., family MSS · U. St Andr. L., corresp. and papers · Westm. DA, letters :: Birmingham Oratory, corresp., mainly relating to his biography of J. H. Newman · Borth. Inst., corresp. with second Viscount Halifax · Herefs. RO, letters to earl of Lytton · NL Ire., letters to first and second barons Emly · U. Hull, Brynmor Jones L., letters to Ruskin · U. St Andr. L., von Hügel MSS

Likenesses

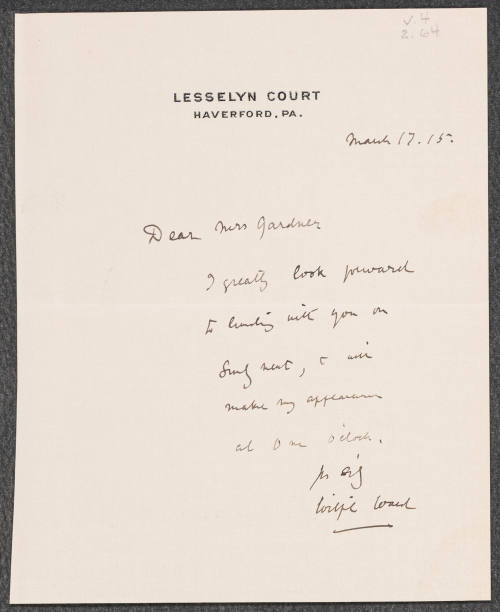

J. Cameron, photograph, 1871, repro. in Ward, The Wilfrid Wards, vol. 1, frontispiece · photograph, c.1913, repro. in Ward, The Wilfrid Wards, vol. 2, frontispiece [see illus.]

Wealth at death

£10,658 16s. 4d.: probate, 21 June 1916, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–16

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Sheridan Gilley, ‘Ward, Wilfrid Philip (1856–1916)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2007 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/36737, accessed 24 Oct 2017]

Wilfrid Philip Ward (1856–1916): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36737

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

London, 1801 - 1890, Birmingham, England

Headingley, England, 1835 - 1913, Ashford, England

Preston, Lancashire, England, 1859 - 1907, London

Ambrières, France, 1857 - 1940, Ceffonds, France

Harrow, England, 1829 - 1888, London

Roxborough, Ireland, 1852 - 1932, Coole, Ireland