Image Not Available

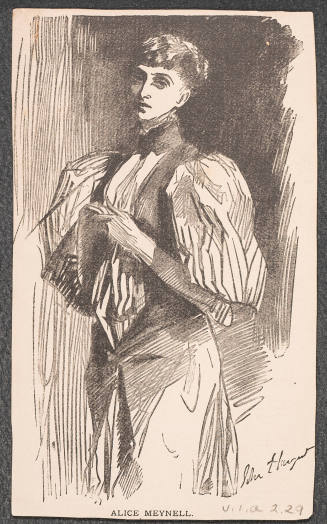

for Francis Thompson

Francis Thompson

Preston, Lancashire, England, 1859 - 1907, London

LC heading: Thompson, Francis, 1859-1907

found: Brit. authors of the 19th cent., 1936: p. 618 (Thompson, Francis Joseph; b. 12/18/1859; d. 11/13/1907; poet and essayist.

Biography:

Thompson, Francis Joseph (1859–1907), poet and writer, was born on 18 December 1859 at 7 Winckley Street, Preston, Lancashire. He was the second son of Charles Thompson (1819–1896), a physician specializing in homoeopathic medicine, and Mary Turner Morton, (1822–1880), who came from a Manchester business family. An older brother had died at birth the previous year and two sisters, Mary and Margaret, were born in 1861 and 1863, after the family moved to a more spacious home in nearby Winckley Square. In 1864 they settled in Ashton under Lyne on the outskirts of Manchester. Both parents were converts to Roman Catholicism who like hundreds of others had followed Cardinal Newman's lead as a direct result of the Oxford Movement. In addition they were influenced by the solid and unemotional faith of the north-country families who had survived the penal days and developed in consequence a characteristic independence of outlook. They passed these influences on to their son, whose firmly grounded faith was to withstand severe tests. But although two uncles, Edward Healy Thompson and John Costall Thompson, had published minor collections of poetry and prose, there was no precedent in the family background for Francis's poetic career. His love of poetry was clear from the start, while according to his sister Mary he ‘wished to be a priest from a little boy’ (Boardman, 18). In 1870, at the age of eleven, he was sent to St Cuthbert's College, Ushaw, near Durham, for an education designed to lead to the priesthood.

From there Thompson acquired his knowledge of Catholic liturgy and there too he began to keep the notebooks which became a lifelong habit. Starting with the ‘Ushaw College notebook’ they number well over a hundred, mostly cheap exercise books, filled with drafts at all stages for his poetry and prose and interspersed with ideas and comments on anything from the issues of the day to memos for nightshirts or trouser buttons. They reveal more clearly than any other source his erratic and unpractical temperament, contrasted with the methodical care that characterizes his method of poetic composition. With a few exceptions the ‘Ushaw College notebook’ gives little indication of the future poetry, but it shows his schoolboy enthusiasm for the Romantic literature of the time, overriding other interests. Its rich, sensuous imagery and its visual qualities are reminiscent of his early favourite, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, while his preoccupation with medieval themes and ideas are clearly influenced by Tennyson as well as the Pre-Raphaelites. These inclinations were not considered compatible with a priestly vocation and in 1877 he left Ushaw to start a medical training at Owens College, Manchester, soon to become part of the Victoria University of Manchester.

Here Thompson struggled on for the next six years, escaping whenever he could to the city library and art gallery. The training left him with the nightmarish memories of the contemporary operating theatre and dissecting rooms that give his poetry some of its most compelling imagery. But it also left him with his lifelong respect for science and its contributions to the modern world. Shortly before his twenty-first birthday his much loved mother died from a painful disease for which opium was the only relief. Almost certainly it was this which gave rise to his own addiction to the drug. During his creative years he was to learn to keep it in check and, contrary to the view of some critics, such as J. C. Reid or G. Grigson, until his last months it was seldom excessive. But it was undoubtedly so during the three years following the final break with his family soon after it became clear he would never make it to the medical profession.

Thompson went to London in the autumn of 1885 and after a few months' desultory employment he was driven to live on the streets. The few pennies he could earn by calling cabs and selling matches went on the opium that was his only respite. The notebooks surviving from these years, damp-stained and often now barely legible, are the most poignant witnesses to his mental and physical suffering. Yet there was another side, for the notebooks record many small acts of kindness from his fellow outcasts. One such encounter stands out from the rest. In autumn 1887 he came close to suicide, from which he was rescued by a prostitute who took him back to her lodgings and looked after him through that winter. Nothing is known of her or of their relationship except that she encouraged him to write his poetry and it continued until the turning point came for him the following spring.

A year before, in February 1887, Thompson had sent some manuscripts of poems and an essay to Wilfrid Meynell, editor of the Catholic literary journal Merry England. But they were mislaid for the intervening months until, on finding them, Meynell recognized their merit and tried unsuccessfully to trace the poet. He therefore printed one of the poems, ‘The Passion of Mary’, in the Easter issue of his journal: and Thompson, by an almost incredible chance, heard of it. But it took several meetings with Wilfrid Meynell and his wife, Alice, a poet in her own right, before he would agree to leave the streets and accept their hospitality. He did so when the street girl, aware she would be a hindrance now rather than a help, disappeared from her lodgings. Despite his efforts to find her she had gone from his life: but never from his grateful memory, as entries in the notebooks testify as well as poems both published and hitherto unpublished.

A period of recuperation was needed and in February 1888 Thompson went to stay at the Premonstratensian priory in Storrington, Sussex. Here, having overcome the symptoms of opium withdrawal, his poetic gifts appeared at last in two major poems, the ‘Ode to the Setting Sun’ and ‘The Hound of Heaven’. Different as the two are, both poems take the theme of death and rebirth beyond the specific Christian context, relating it to some of humanity's most universal aspirations. In both, these aspirations are expressed through a wealth of cosmic imagery that is unique to Thompson. In ‘The Hound of Heaven’, his best-known poem, the flight of the soul from God reaches from within ‘the labyrinthine ways’ of the human mind with its ‘Titanic glooms of chasmèd fears’ to ‘the gold gateways of the stars’ (ll. 3, 8, 26). When the flight is over, the self-confrontation that follows takes place in a cosmic setting centred on ‘the hid battlements of eternity’ (l. 145) and the cry of Everyman against his human limitations:

Whether man's heart or life it be which yields

Thee harvest, must Thy harvest fields

Be dunged with rotten death?

(ll. 152–4)

Though the poem is rooted within Thompson's Catholic background, his later experiences had widened his vision to embrace, in the final resolution, a restoration that extends beyond any particular creed.

Thompson was back in London early in 1890, spending most of his days at the Meynells' home assisting them with their journalistic work. Here he met the varied circle of their friends and colleagues who, according to the Meynells' daughter Viola, were marked by ‘strong independent views, not afraid to be the exception’. In their company his shabby, nondescript appearance went with his diffident manner, recalled by Viola as ‘silent, repetitive or irrelevant’ (V. Meynell, 65, 86). Yet when roused he could be eloquent on subjects where he felt confident and he shared in many of their more liberal views. His prose writings for the Meynells' journals were often critical of the social and religious attitudes of the time. The most notable was the essay ‘In Darkest London’, which appeared in Merry England (January 1891; the version printed in The Works of Francis Thompson, 1913, contains unacknowledged deletions as well as additions from other sources). It drew on his own experiences in showing up the inadequacy of the provisions made for the homeless. With the outstanding exception of the Salvation Army the prevailing response to the population of the streets was too often one of condemnation. You had to deserve mercy, divine or human.

Apart from his poetry and other writings Thompson was developing another interest, begun in the library and art gallery in Manchester and not discarded even during the dark years on the streets. Until turned away on account of his ragged clothing he would spend hours at the Guildhall Library or the National Gallery. Now he was again spending his free time reading widely on all aspects of ancient beliefs and the symbolism by which they were expressed. He kept his studies within the privacy of his notebooks since for Catholics such preoccupations were highly suspect. But his knowledge of these subjects enhances many of his poems, as can now be recognized in the wider context that he had in mind.

During 1892 the demands of journalism, the loneliness of his lodgings, and the need for time to write his poetry began to tell and the Meynells were aware that Thompson was again taking opium. So they arranged, and he had to agree, for a visit to the Franciscan friary at Pantasa, Flintshire, where he was to remain for the next four years. The magnificent scenery of the Welsh mountains combined with the spiritual and intellectual stimulus of the community gave rise to a period of intense creativity. His first volume of poetry, Poems, appeared in 1893 and provoked strong reactions for and against. Sister Songs, two long poems addressed to two of the Meynell children, was published in 1895 while he was preparing his most extensive collection, New Poems (1897), to which the critical responses showed how little the ideas behind his poetry were appreciated. Most of the more notable poems are concerned with one or another aspect of the incarnation of supernatural life within the human and natural order. In ‘From the Night of Forebeing’ he reinterprets the Easter liturgy of the resurrection in terms of renewal in the natural world and within his own soul. ‘Assumpta Maria’ celebrates the bodily assumption of the Blessed Virgin into heaven as the ultimate effect of incarnation as he understands it. Furthermore he identifies the role of the Blessed Virgin as queen of heaven with the pagan goddesses who were her precursors. Significantly, after his death the central three stanzas were deleted from all editions published to date. But by now Thompson was full of doubts as to the future of his poetry. Drawing down the supernatural, as it were, within the natural world, might be only a short step from an over-identification with materialistic aims and values that would undermine all he desired his poetry to express. It must wait for an age when harmony between the three orders of existence, supernatural, natural, and human life, would be recognized as essential to the continuing well-being of creation as a whole.

Thompson's friendship with Coventry Patmore contributed to this dilemma. Though it was fruitful in their shared interest in ancient religions and symbolism, Thompson was unable to accept the extent of the older poet's identification between divine and human love—underlined as it was by a mutual infatuation for Alice Meynell which Thompson, unlike Patmore, was able to surmount (Boardman, 232–4). Thompson was aware that his creative life as a poet was waning by this time. But after his return to London, shortly after Patmore's death in 1896, in the prose writings of his later years he was constantly exploring the ideas and aims of the poets of the past and of his own day. His numerous reviews and carefully structured essays have been unfairly neglected, as also the monograph Health and Holiness, published in 1905 with a preface by George Tyrrell—already a controversial figure on account of his ‘modernist’ views. Here Thompson's study of the relations between spiritual and physical health is well ahead of his time. His later odes, although usually commissioned for public occasions, contain passages worthy of his earlier work.

During these years Thompson's friendship with Katharine Douglas King, known as Katie, could have developed further if his circumstances and temperament had been different. They shared their concern for the London poor and her novels of London life, drawn from her own experiences, still await recognition. Her death in 1900 left him with little to lighten his last years apart from his lifelong enthusiasm for cricket and writing the humorous verse that he usually kept to the privacy of his notebooks. Lines from his unfinished poem ‘At Lords’ have become part of cricket literature but others of his cricket poems remained virtually unknown until the publication of the new edition of his work in 2001.

Towards the end of his life Thompson's opium habit increased, mainly to relieve the symptoms of his declining health. He did not then or at any time suffer from tuberculosis, as has been generally believed. Drawing on his medical knowledge he himself diagnosed the disease as beriberi, originating from his years of deprivation and complicated by the opium and his erratic way of life. This has been professionally confirmed by a medical expert in retrospective diagnosis (Boardman, 314–15, 392, n. 14). The best likeness of Thompson dates from these last months in the pencil sketch by Neville Lytton.

Thompson died on 13 November 1907 at the Hospital of St John and St Elizabeth, London, and was buried on 16 November at Kensal Green Roman Catholic cemetery. The only possessions at his lodgings were some old pipes, the toy theatre he had played with as a child, and a tin trunk full of papers. These were manuscripts and notebooks accumulated over forty years, from which Wilfrid Meynell edited both poetry and prose for publication in journals and in the so-called Works of Francis Thompson (3 vols., 1913). The extent of Meynell's alterations and deletions has not been recognized, as all subsequent editions were based on the Works. The new edition of the poems restores original texts and adds others hitherto unpublished.

Brigid M. Boardman

Sources B. M. Boardman, Between heaven and Charing Cross: the life of Francis Thompson (1988) · J. E. Walsh, Strange harp, strange symphony: the life of Francis Thompson (1968) · The letters of Francis Thompson, ed. J. E. Walsh (New York, 1969) · E. Meynell, The life of Francis Thompson (1913) · V. Meynell, Francis Thompson and Wilfrid Meynell (1952) · O. Chadwick, The Victorian church, 2 vols. (1966–70) · K. Chesney, The Victorian underworld (1970) · H. Jackson, The eighteen nineties: a review of art and ideas (1988) · D. Matthew, Catholicism in England, 1598–1935, rev. 2nd edn (1948) · T. M. Parssinen, Secret passions, secret remedies: narcotic drugs in English society, 1820–1930 (1983) · H. Mayhew, London labour and the London poor, 4 vols. (1861–4) · M. Secker, The eighteen nineties (1948) · The poems of Francis Thompson, ed. B. Boardman (2001) · J. Thomson, Francis Thompson, the Preston-born poet (1912) · b. cert.

Archives Boston College, Massachusetts, corresp. and papers · Harris Library, Preston, commonplace book, poetical MSS, letters; notebooks and literary MSS · Indiana University, Bloomington, Lilly Library, corresp. and writings · Lancashire Library, Preston, commonplace book, poetical MSS, letters, notebooks, and literary MSS · State University of New York, Buffalo · Ushaw College, Durham, commonplace book

Likenesses Elliott & Fry, photograph, 1880–89, NPG [see illus.] · E. Meynell, oils, 1906, priv. coll. · N. Lytton, chalk drawng, 1907, NPG · N. Lytton, pencil sketch, 1907, Boston College, Chesnut Hill, Massachusetts, J. J. Burns Library · N. Lytton, pastel sketch, 1945, Boston College, Chesnut Hill, Massachusetts, J. J. Burns Library · J. Lavelle, oils (after N. Lytton), Boston College, Chesnut Hill, Massachusetts, J. J. Burns Library · E. Meynell, plaster cast, NPG

Wealth at death no possessions apart from MSS and other papers

© Oxford University Press 2004–15

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Brigid M. Boardman, ‘Thompson, Francis Joseph (1859–1907)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/36489, accessed 16 Oct 2015]

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Fockbury, England, 1859 - 1936, Cambridge, England

Worcester, 1859 - 1939, Worcester

Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England, 1852 - 1948, Pulborough, England

Ledbury, England, 1878 - 1967, near Abingdon, England

Bradford, Yorkshire, 1872 - 1945, Far Oakridge

Kolkata, India, 1811 - 1863, London

Walmer, England, 1844 - 1930, Oxford, England