Edith Wharton

New York, 1862 - 1937, Val-d'Oise, France

LC Heading: Wharton, Edith, 1862-1937

Wharton, Edith (24 Jan. 1862-11 Aug. 1937), writer, was born Edith Newbold Jones in New York City, the daughter of George Frederic Jones and Lucretia Rhinelander. To all appearances Edith Newbold Jones, as the youngest child of a well-to-do couple of fashionable old New York, led a privileged childhood and adolescence, which included winters in Paris, summers in Newport, Rhode Island, and the social season in New York, with its lavish balls and elegant dinners. But according to "Life & I," an unusually candid autobiographical fragment written in the early 1920s, Wharton's early years were anything but secure. She depicts herself as a deeply anxious child because of her cold and distant mother. As a bookish girl lacking in self-confidence, Wharton saw herself falling short of her mother's and her society's expectations for a young woman, whose purpose in life was to make a socially advantageous marriage. As Wharton saw it, Lucretia Jones thwarted her natural inclinations, depriving her of a regular supply of writing paper, accelerating the date of her debut (so that Wharton would have less time to read), and preventing an engagement with a man of Wharton's choosing. Wharton spent most of her early years retreating into the world of "making up," as she called her irresistible passion for telling stories, which prepared her for a career as a professional novelist and writer. By the time she was sixteen, Wharton had published several poems and had written a novel, Fast and Loose (first published in the Apr. 1978 issue of Redbook), to which she appended parodies of literary reviews.

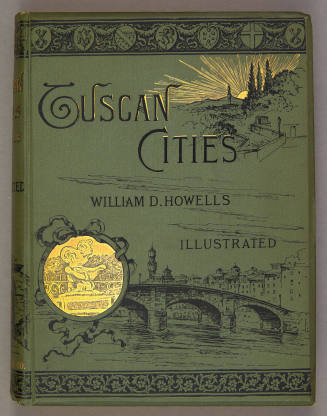

In 1885 Edith Newbold Jones married Edward "Teddy" Robbins Wharton of Brookline, Massachusetts, who shared Edith's love of dogs, horses, and outdoor activity. The two, who remained childless, were poorly matched, however. Teddy had little understanding of and appreciation for his wife's intellectual life; Edith had little stomach for the social rituals in which the easygoing Teddy flourished. From the very start, their conjugal life was a disaster, with Edith blaming her mother for her sexual ignorance, which did "more than anything else to falsify & misdirect my whole life." Wharton could escape the constrictions of old New York only when the couple traveled in Europe each winter, where Wharton began to cultivate a circle of friends that included French writer Paul Bourget, art critic Bernard Berenson, and essayist Vernon Lee (Violet Paget). Her European travels were the basis for her early published work. Her first book, The Decoration of Houses (1897), written with architect Ogden Codman, was the result of her observation of European architecture and interior decoration; the essays collected in Italian Villas and Their Gardens (1904), Italian Backgrounds (1905), and A Motor Flight through France (1908) first saw publication as travel articles popular in magazines such as Scribner's and Century. Wharton's travel writings are noteworthy on several counts: she was one of the first writers to realize the potential of the automobile to change the face of travel; more important, she demonstrated an ability to capture local atmosphere, an extensive knowledge of history, art, and culture, and an exceptionally sensitive eye for detail and nuance.

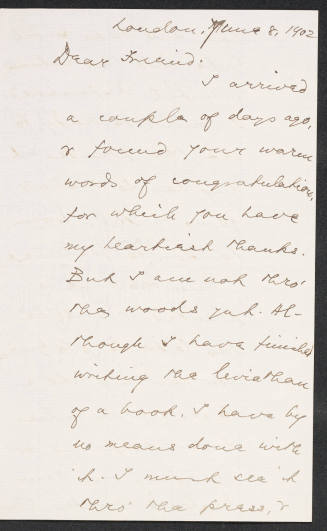

At the same time she was writing her travel essays, Wharton was also publishing short stories, so much so that her publisher, Charles Scribner's Sons, proposed several collections of her fiction. These volumes--The Greater Inclination (1899), Crucial Instances (1901), and The Descent of Man (1904)--were delayed by a series of psychosomatic illnesses, most likely brought on by the frustration of her marriage to Teddy, a frustration heightened by her intellectual and professional growth as her circle of friends expanded and her confidence as a writer grew. The publication of her first novel, The Valley of Decision (1902), clearly reflects this confidence. A novel of settocento Italy, The Valley of Decision was favorably compared to George Eliot's Romola. It showcases Wharton's painstaking research and introduces a theme that dominates her subsequent fiction: striking a balance between the stability of tradition and the inevitability of change.

The Valley of Decision also brought Wharton to the attention of Henry James, a novelist whom she had long admired, but it was Wharton's next novel, The House of Mirth (1905), that solidified a vigorous friendship that flourished until James's death in 1916. This friendship, documented in Lyall H. Powers's Henry James and Edith Wharton: Letters, 1900-1916 (1990), included frequent motor trips on the Continent and in the United States, shared acquaintances, and an amicable professional rivalry. James praised The House of Mirth as "altogether a superior thing"; more important, the 1905 novel, a popular and critical success, marked Wharton's debut as a talented and perceptive critic of American manners. The House of Mirth, with its strong naturalist overtones, chronicles the final years of Lily Bart, a young woman without parents or fortune, who must "barter" her beauty for an advantageous marriage. Her fine moral sensitivity, however, repeatedly gets in the way of social and practical expedience; the novel ends as she dies, alone and poor, in a boardinghouse. With this novel Wharton recognized, as she would note in her 1934 autobiography, A Backward Glance, that her true subject was the society of old New York and "its power of debasing people and ideals"; Wharton's best work is that in which she explores her ambivalence for old New York's continuity of tradition and its "frivolity."

Although Wharton invested in the construction of "The Mount," a mansion near Lenox, Massachusetts, completed in 1902 and incorporating the principles of design described in The Decoration of Houses, her interests increasingly lay in Europe, particularly in France. Included among Wharton's friends was an American-born journalist, Morton Fullerton, who wrote for British and French newspapers. By 1909 the two were involved in an affair (despite Fullerton's reputed engagement to his cousin Katherine Fullerton) that lasted two years. In this affair Wharton finally attained sexual fulfillment, which in turn enabled her to explore the darker sides of the human psyche. This exploration is evident in the highly popular 1911 novel Ethan Frome, which describes the love triangle of Ethan Frome, his wife Zeena, and his wife's cousin Mattie Silver, set in the winter isolation of aptly named Starkfield, Massachusetts. This novel presented a departure from Wharton's usual subject, the social elite of New York, as does the 1917 novel Summer, which Wharton herself characterized as her "hot Ethan." Also set near Starkfield, Summer recounts the sexual awakening of Charity Royall, who marries her guardian the lawyer Royall after Lucius Harney impregnates and abandons her.

Wharton's relationship with Fullerton and the mastery of her craft--by 1912 she was a well-regarded writer of fiction who commanded substantial prices for her work--further widened the gap between Wharton and her husband, who on his side contributed to the breakdown of the marriage by his own sexual escapades and by what Wharton perceived as increasingly erratic behavior. In 1913 Edith divorced Teddy, though she contributed to his medical expenses as his mental and physical condition deteriorated; he died on 7 February 1928. Wharton's divorce was clearly a watershed in her emotional life. She never remarried, though she did maintain a close friendship with Walter Berry, whom she had known since her teens, who frequently traveled with her, and whose death on 12 October 1927 she deeply mourned. Another watershed of sorts, World War I, occurred a year after her divorce. Wharton enlisted her pen in persuading the United States to come to France's aid. In Fighting France (1915), a series of essays based on her visits to the front lines, she wrote eloquently of her "vision of all the separate terrors, anguishes, uprootings and rendings apart . . . all the thousand and one bits of the past that give meaning and continuity to the present--of all that accumulated warmth nothing was left but a brick-heap and some twisted stove-pipes." She also worked tirelessly to help Belgian refugees, establishing schools and orphanages for them in Paris. King Albert of Belgium awarded her the Medal of Queen Elizabeth and named her chevalier of the Order of Leopold, while the French government recognized her work by making her a chevalier of the Legion of Honor and sending her to French Morocco to report on the efforts of General Hubert Lyautey to modernize the colony. In Morocco (1920), her last travel book, chronicles her travels through Morocco accompanied by Berry and includes vivid descriptions of religious festivals, colorful souks, and the harems, which she compared to ornate sepulchers.

While the 1910s were years of upheaval in Wharton's life, the same decade saw the publication of a series of masterpieces: Ethan Frome; The Reef (1912), a somewhat Jamesian analysis of a troubled relationship; The Custom of the Country (1913), a scathing critique of a predatory American girl and the society that spawned her; and Xingu and Other Stories (1916). With The Age of Innocence in 1920, a new note entered Wharton's fiction: mourning for "the old ways"--the decencies of life and the need for continuity and tradition--forever lost in the cataclysm of the Great War. The Pulitzer Prize-winning novel is Wharton's finest expression of her ambivalence over tradition and modernity. In telling the story of Newland Archer, who must choose between the stability of a safe marriage and the excitement of an affair, Wharton delicately balances the constricting power of convention with the bittersweet recognition that "after all, there was good in the old ways," particularly in contrast to the present, a "kaleidoscope where all the social atoms spun around on the same plane."

As Wharton surveyed her native land from the vantage point of France, she was increasingly dismayed by the rampant materialism and vulgarity of the 1920s. Her novels during this period--The Glimpses of the Moon (1922), A Son at the Front (1923), The Mother's Recompense (1925), Twilight Sleep (1927), The Children (1928), and Hudson River Bracketed (1929), as well as the four novellas collected in Old New York (1924)--condemn a society gone awry while attempting to come to terms with issues of the day such as eugenics, companionate marriage, and the culture of advertising. Critics maintained that by expatriating herself, Wharton had lost touch with what was admirable in American culture. Although her popularity declined throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Wharton's work continued to sell in spite of the economic depression and changing tastes in literature. An indication of Wharton's stature as a writer was the award of an honorary doctorate of letters from Yale University in 1923. She was the first woman Yale so honored, and the June ceremony in which she received the award was the occasion of her final visit to the United States.

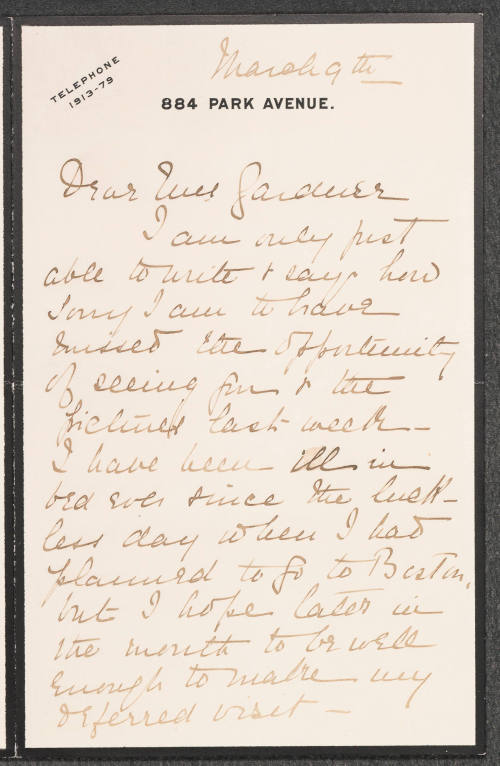

From October 1933 to April 1934 the Ladies' Home Journal published a series of autobiographical essays by Wharton. These were later published as A Backward Glance. Wharton's autobiography recounts her childhood years of reading, describes her European travels, sketches her approach to writing (which she had discussed more fully in The Writing of Fiction in 1925), and paints affectionate portraits of her friends, with Henry James's being the most vivid. What is most notable about A Backward Glance, however, is what it does not tell: her criticism of Lucretia Jones, her difficulties with Teddy, and her affair with Morton Fullerton, which did not come to light until her papers, deposited in Yale's Beinecke Rare Book Room and Manuscript Library, were opened in 1968.

In her later years, after the war, Wharton devoted herself to writing; to renovating two residences in France, the Pavillon Colombe in Saint-Brice-Sous-Fôret and the Chateau Sainte-Claire in Hyères, on the French Riviera; and to gardening. Wharton's niece, Beatrix Jones Farrand, assisted her in the planning of the grounds at Pavillon Colombe and Sainte-Claire. Her final years were marked by the deaths of close friends and beloved dogs. Wharton died at Pavillon Colombe after a series of strokes. She is buried near Walter Berry in the Cimetière des Gonards at Versailles; her gravestone bears the epitaph she chose: Ave Crux Spes Unica.

In the years following Wharton's death, her novels and short stories continued to be read. Serious criticism and scholarship were sparked, however, by the opening of her papers in 1968 and the publication of two major biographies: R. W. B. Lewis's Edith Wharton: A Biography (1975) and Cynthia Griffin Wolff's A Feast of Words: The Triumph of Edith Wharton (1977). With these two works, coinciding with the growing interest in women's writing and women's studies, the fiction of Edith Wharton was recognized as a significant contribution to American literature. Although during her lifetime Wharton wrote numerous short stories, several volumes of travel essays, nonfiction, poetry, and an autobiography, her fame rests primarily on her novels, particularly those in which she examines and critiques American manners and culture. In her writing, Wharton exhibited that rare ability to combine artistic integrity with popular appeal. Her themes--the necessary price an individual pays to be a part of society, and the conflict between stability and change--continue to remain relevant to the American experience.

Bibliography

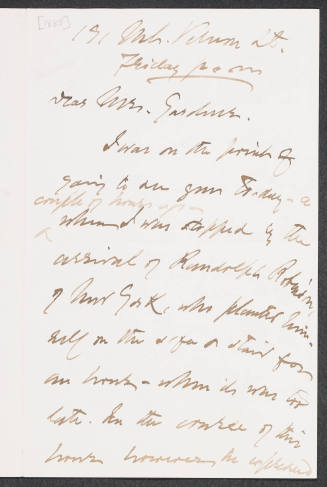

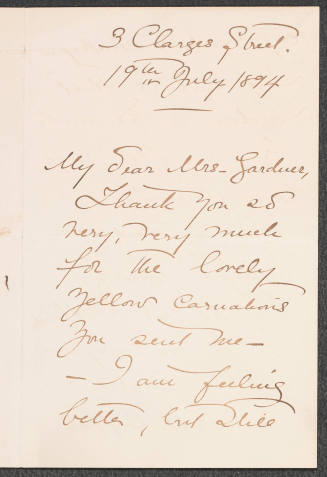

The majority of Wharton's papers--notebooks, manuscripts, professional and personal correspondence, and photographs--is in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book Room and Manuscript Library, Yale University. Diaries, some correspondence, and estate documents can be found at the Lilly Library, Indiana University: The Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas, Austin, holds Wharton's letters to Fullerton. Other major collections of letters are held by the William Royall Tyler Collection, Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C., and by the Harvard Center for the Study of Renaissance Art at Villa I Tatti, Settignano, Italy. Additional letters are at the Robert Frost Library at Amherst College and at Harvard University's Houghton Library. The Scribners archive in the Firestone Library at Princeton University contains the largest collection of Wharton's correspondence with her publishers. In addition to those novels discussed above, Wharton wrote The Fruit of the Tree (1907), The Marne (1918), and The Gods Arrive (1932); The Buccaneers, uncompleted, was published posthumously in 1938. Novellas include The Touchstone (1900), Sanctuary (1903), and Madame de Treymes (1907). Wharton's short stories can be found in the two volumes of The Collected Short Stories of Edith Wharton (1968). See Wolff, Feast of Words, for a complete bibliography of her work, fiction and nonfiction, including reviews and essays. Lewis's and Wolff's biographies--the former a good source for the day-to-day details of Wharton's life, the latter an analysis of the relationship between Wharton's life and her writing--have been supplemented by two additional works. Shari Benstock, No Gifts from Chance: A Biography of Edith Wharton (1994), details Wharton's dealings with her publishers. Eleanor Dwight, Edith Wharton: An Extraordinary Life (1994), an illustrated biography, includes numerous photographs of Wharton, her friends, her homes, and her gardens. For bibliographies of secondary works, see Kristin O. Lauer and Margaret P. Murray, Edith Wharton: An Annotated Secondary Bibliography (1990), and regular updates in the Edith Wharton Review.

Judith E. Funston

Back to the top

Citation:

Judith E. Funston. "Wharton, Edith";

http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-01745.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Tue Aug 06 2013 11:50:25 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Martins Ferry, Ohio, 1837 - 1920, New York

Conway, Massachusetts, 1841 - 1904, New York

Château Saint-Leonard, France, 1856 - 1935, Florence

Butrimonys, Lithuania, 1865 - 1959, Florence

Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1871 - 1950, Washington, DC

Norwich, Connecticut, 1865 - 1952, Paris

Richmond, Virginia, 1863 - 1945, Charlottesville, Virginia