William Dean Howells

Martins Ferry, Ohio, 1837 - 1920, New York

They were rescued in 1852 by radical allies from Ashtabula County, Ohio, which sent an antislavery congressman, Joshua Giddings, to Washington. The family printed the Ashtabula Sentinel, "the voice of Giddings," in Jefferson, Ohio, and slowly paid for their property.

Howells learned sympathy for liberty and social justice at home. Beginning to set type in childhood he acquired habits of hard work that remained to his deathbed. My Literary Passions (1895) and Years of My Youth (1916) tell how the autodidact, schooled largely in the printshop, mastered languages and literatures. Toiling furiously during the hours after he had set a man's daily stint of type, he read English literature and got a literary use of Spanish, Latin, French, and German. Bewitched by the ironies of Heinrich Heine, he distanced himself from earlier passions for Alfred Lord Tennyson and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. He would always feel ambivalent toward romantic and antiromantic sensibilities, though to think and write according to his antiromantic vision made him distinctively Howells.

In all, Howells wrote "about 200 books wholly or in part," say Gibson and Arms. His first publication, a poem, came in 1852. Between 1860 and 1921 appeared thirty-six novels, twelve books of travel, ten volumes of short stories and sketches, seven of literary criticism, five of autobiography, four of poetry, three of collected drama, and two presidential campaign biographies. There were many hundreds of essays, reviews, editorials, speeches, poems, farces, and miscellanea--some of them collected. He published in sixty-four magazines and nineteen newspapers and conducted eight different serial columns. At a time when the media were predominantly literate, Howells was the major presence. This was especially true during the 1890s.

Country newspapers before the Civil War served political interests. In the family shop Howells breathed politics, and he succeeded as a legislative reporter to a Cincinnati newspaper before he was twenty. In 1858 he jumped to an editorial post on the Republican Ohio State Journal in Columbus and became a poet and critic and man-about-town in the city. By 1861 he had placed poetry, fiction, and criticism in nationally conspicuous magazines (Knickerbocker, Saturday Press, Atlantic Monthly) and had published a collection of verse (Poems of Two Friends, 1860) and a campaign biography of Abraham Lincoln. In 1861 Lincoln's secretaries John George Nicolay and John Milton Hay helped this deserving Republican win appointment as the U.S. consul in Venice.

On 24 December 1862 Howells married Elinor Mead (Elinor Mead Howells), a painter and illustrator, at the American embassy in Paris. As Merrill and Arms say, "Their marriage was fulfilling and their life together brimming with fun." She sprang from an extraordinary tribe: John Humphrey Noyes was an uncle and Rutherford B. Hayes a cousin; among her brothers were Larkin Mead the sculptor and William Mead the architect. The Howells had three children, and all were artistically gifted. John Mead Howells became a leading architect.

Elinor Mead Howells seemed to her husband to possess as a critic something akin to absolute pitch. In the retrospect of Years of My Youth he said that "she became with her unerring artistic taste and conscience my constant impulse toward reality in my work." Through the insights of Ginette de B. Merrill it is clear that Elinor Mead was one of the significant women of her era.

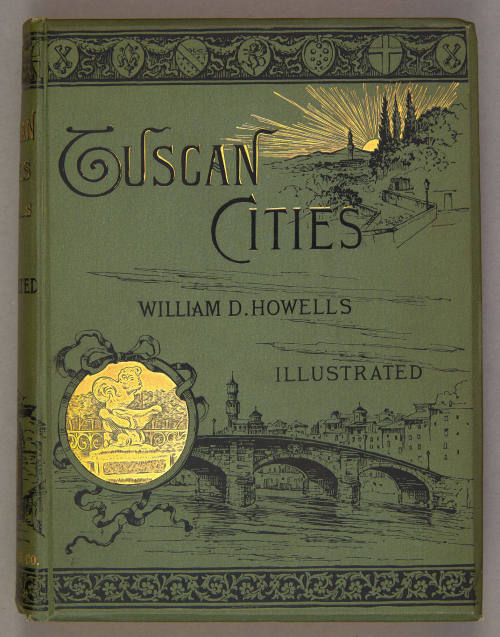

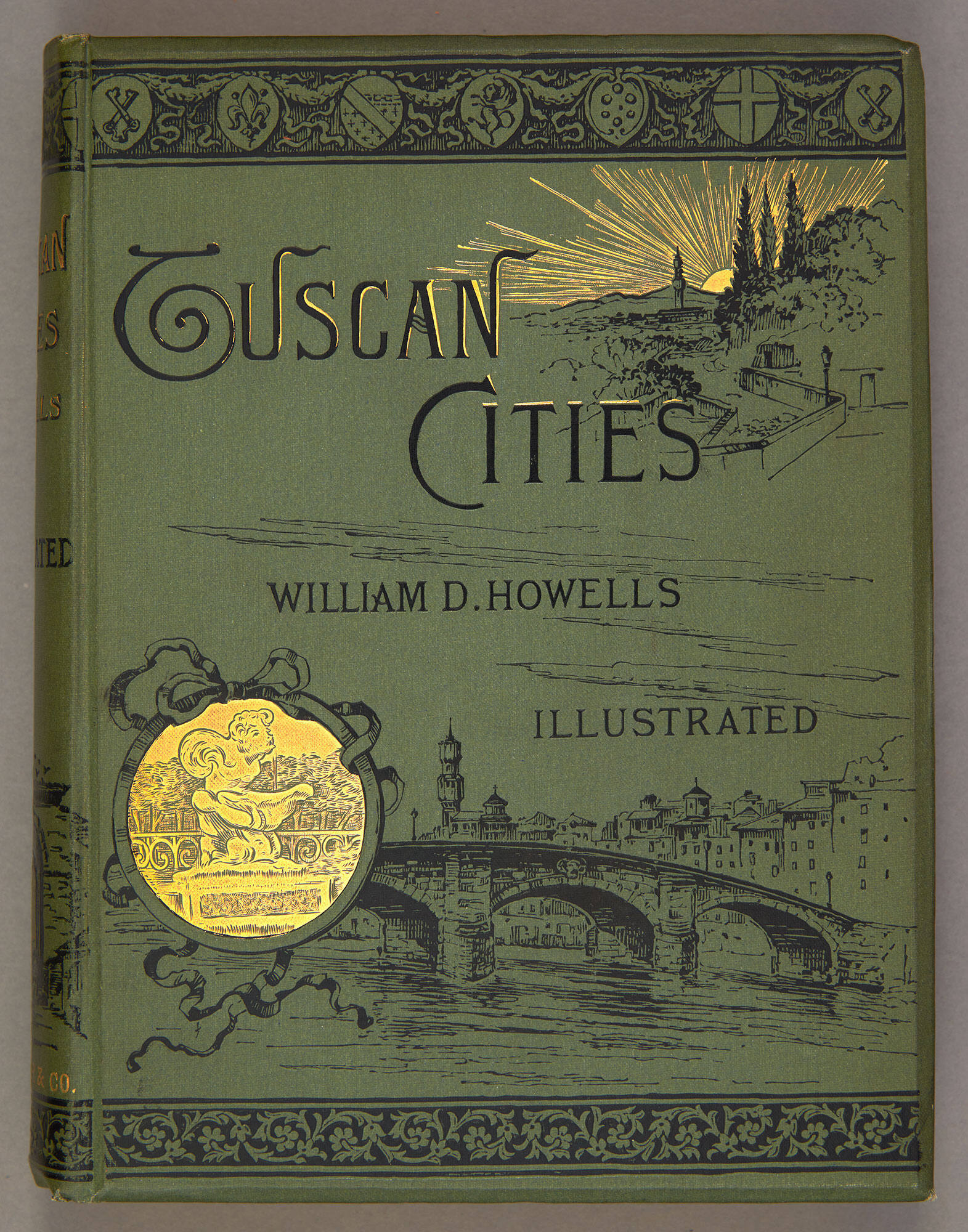

It is not true, though H. L. Mencken casually said it was, that Howells's books had "no . . . ideas in them." Perhaps Howells was too sensitive for Mencken. "Mr. Howells," wrote Hamlin Garland in 1892, "has come to stand for the most vital and progressive principle in American literature" and speaks to "the more radical wing of our literary public." Garland's Howells had begun to emerge with Venetian Life (1866). In Venice the Western radical and Heinesque ironist recognized that the contemporary common life of the people in a ruined and antiromantic city groaning under Hapsburg tyranny interested him, not the dreams of Lord Byron, James Fenimore Cooper, or John Ruskin. The charm of his book has kept it alive to this day. By the time Mark Twain published The Innocents Abroad (1869) he would find Howells, already master of much the same reductive vision, waiting to review the book and applaud him. It began a friendship good for life.

Home from Italy, Howells discovered that the same vision succeeded when he applied it to American realities (Suburban Sketches, 1871; Their Wedding Journey, 1872). Success led him to thoroughly fictional narrative in A Chance Acquaintance (1873) and to paired discoveries. He wished, as he told his friend Henry James (1843-1916), to confront one American sort, the "unconventional"--the native, common, democratic--with the "conventional"--the Europeanized, urban, aristocratic--American type. And, as he wrote his father, his preference for the "unconventional" American elated him: it proved that he felt "the true spirit of Democracy."

Howells experienced that elation, that adventure in ideas, at a time when some critics have believed that he was smothered under the conventionalities of Boston and Cambridge. In fact he had launched what Annie R. M. Logan called in 1890 "A series appropriately entitled 'Boston Under the Scalpel' or 'Boston Torn to Tatters.' " When he came home after the Civil War, Howells went to New York to establish a literary career. He was scarcely settled into a job on E. L. Godkin's Nation when James T. Fields came to recruit him as assistant editor of the Atlantic Monthly.

That was the best job in the world for Howells. He began work on 1 March 1866, his twenty-ninth birthday. The literary nation took note. A western phenomenon, poet, critic, and authority on contemporary Italian literature was now second in command of the flagship American magazine. He lived in Cambridge, close to the press to which proof corrections took him. In truth, Howells hardly ever lived in Boston: only a relatively few months in 1883-1884 and again in 1890-1891 before he moved to New York on 8 November 1891.

For about a dozen years, from 1866 to 1878, Cambridge seemed "the perfect home." The Howells family moved around in it so regularly that they appeared nomadic. The Fireside Poets Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809-1894), Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and James Russell Lowell were Harvard professors with national reputations. Howells, with his gift for friendship, won theirs and would focus Literary Friends and Acquaintance (1900) on them because by that time they and Old Cambridge were dead, and decorum allowed him to stand as a privileged witness. Longfellow admitted Howells to the weekly sessions of the Dante Club. Holmes gave him spiritual counsel. Lowell took him on long walks and talked for hours on end about literature and how to build a career. Only hints, however, of other, more important associations in Cambridge appear in Literary Friends. At that moment the town sparkled as one of the most exciting intellectual centers in the United States.

Fields assigned Howells to recruit new writers for the Atlantic; Howells obliged, and his coevals felt gratified. Business aside, he formed friendships with three older men: Henry James, Sr. (1811-1882), Charles Eliot Norton, and Francis Child. But the true galaxy consisted of people about his own age: William James, Henry James (1843-1916), and Alice James; Henry Adams (1838-1918) and Brooks Adams; John Fiske (1842-1901); and the younger Oliver Wendell Holmes (1841-1935).

In Cambridge, Howells learned to deal with the chief ideas of his day. The intellectual atmosphere was intense, stimulating, international: philosophic and scientific as well as aesthetic. New thought, especially Darwinism in its permutations, agitated the town and forced its way into the book reviews in the Atlantic--of which Howells had charge and wrote many. His fiction became increasingly sophisticated in fine novels like A Foregone Conclusion (1875) and The Undiscovered Country (1880), as he learned techniques and stances from new literary passions like Turgenev. He began to write a novel a year.

In 1881 Howells resigned his editorship to devote himself to fiction. His vision deepened and darkened in works like A Modern Instance (1882), The Rise of Silas Lapham (1885), and Indian Summer (1886). Losing the moral euphoria of the postwar years and uneasy about industrializing, urbanizing America, Howells and his generation felt qualms about romantic, democratic American life. His work began to look to humane values: the ethics of "the economy of pain" (Lapham) and "complicity" (The Minister's Charge, 1887) and "solidarity" (Annie Kilburn, 1889). Tolstoy hit him with a force almost equal to religious conversion. In A Hazard of New Fortunes (1890), he discovered another basis for his concern with ethical principles. It may be that the sins of evil persons find vicarious atonement in the suffering of the good.

The years 1886 to 1891 were a time of "black care" for Howells despite the fact that the period began with a stroke of wonderful professional luck. The good luck came in the contract he signed with Harper & Brothers in 1885. For an annual salary of $10,000 he was to write a novel a year to be serialized in Harper's Monthly, plus a monthly column on subjects of his choosing. The money and security were, he said, "incredibly advantageous." "The Editor's Study" began in January 1886 with a bang. Soon Howells became a fighting critic who espoused the modern, the democratic and common, even contending for "the superiority of the vulgar" over Matthew Arnold and against British resistance to international literary realism. He argued for sociopolitical compassion and reform even to the point of socialism. The wide public for Harper's Monthly discovered in the "Study" Edward Harrigan and James A. Herne, Dostoyevsky, Emily Dickinson, Hamlin Garland, William James, Harold Frederic, and the contemporary Spanish realists. Howells praised American women local colorists and George Washington Cable, Henry James, Emile Zola, Mark Twain, John William De Forest, and, of course, Tolstoy. The "Study" employed terms like "neo-romantic" and "effectism." Opponents both native and transatlantic fired back a barrage of often slanderous retort.

The last "Study" appeared in March 1892, but during its course Howells passed through events so momentous they made the troubles of his critical controversies trivial by comparison. His daughter Winifred was stricken with a mysterious illness and died in 1889. Her health had been blighted for nine years, and she spent most of the years after 1886 in sanatoriums.

Simultaneously, Howells faced the most menacing crisis of conscience in his life. On May Day 1886 American labor unions went on strike for an eight-hour workday. In Chicago the police were murderously violent in putting down the strike. On 4 May police tried to break up a mass protest in the Haymarket Square. Someone threw a bomb, and several policemen were killed. With no actual suspects available, authorities rounded up eight Anarchists, tried them for murder on charges of advocating and inciting to violence, found them guilty, and sentenced seven of them to be hanged. Howells felt morally outraged: they were to be hanged for expressions of opinion. He thought their opinions "frantic" but considered the miscarriage of justice intolerable. He published letters in the New York Tribune and the Chicago Tribune in which he argued for gubernatorial clemency to commute the death sentences.

Howells stood alone among American celebrities in this act of conscience and common sense. The press ridiculed and damned Howells and rejoiced when four Anarchists were hanged on 11 November, a fifth having committed suicide. Howells risked his professional reputation for a moral principle. Luckily he lost only his fight for liberty of speech and conscience, not his livelihood. The popular success of A Hazard of New Fortunes, which dealt with issues of wealth and poverty, capital, labor, socialism, urban crisis, and violence, vindicated him.

Many students of Howells have ignored all or most of his last thirty years. Yet much of his best work, including a number of developments and departures, took place during these years. Howells stepped forward into the nascent modernist movement. Between 1890 and 1900 he published thirteen novels, four memoirs, and a book each of poetry, criticism, and collected essays. He ran three series of columns. He championed Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Stephen Crane, Frank Norris, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Charles Chesnutt, Abraham Cahan, Thorstein Veblen, Henrik Ibsen, and George Bernard Shaw, demolished Max Nordau, and defended Anna Karenina and The Kreutzer Sonata. He developed as a feminist, an anti-imperialist, an egalitarian, and a socialist. He moved toward psychological realism and produced utopian romances.

Other important books from the 1890s are: The Shadow of a Dream (1890), a pre-Freudian study of a complex sexual triangle; A Boy's Town (1890), which fascinated Dr. S. Weir Mitchell for its insights into childhood terror; An Imperative Duty (1893), a miscegenation novel praised by W. E. B. Du Bois; The Quality of Mercy (1892), the study of a business man turned fugitive embezzler; A Traveller from Altruria (1894), a utopian romance; Stops of Various Quills (1895), a collection of dark, modernist poetry; and The Landlord at Lion's Head (1897). During the 1890s Howells was virtually a literature in himself.

Psychic motives partly spurred Howells's prodigious output. Against the Haymarket crisis and the "Study" fight he reacted with creative indignation. His daughter's illness and death almost silenced him, but he rebounded because work was his solace and refuge. He carried a message to the disintegrating world: The World of Chance he called it in an interesting novel of 1893. New personal economic realities also motivated him. With other publishers wooing him, Howells and the Harpers agreed to disagree before his contract expired. On 1 January 1891 he became a freelancer. At the end of the year he moved to New York to edit Cosmopolitan magazine, owned by a reform-minded millionaire. Howells hoped, as he said, "to do something for humanity as well as the humanities." But he and the millionaire had misunderstood each other, and Howells was free again by June.

Howells's work was serialized in various periodicals, but Harper & Brothers published his books. Howells was shocked, then, when Harper & Brothers failed in November 1899. As soon as he could, however, George Harvey, the new head of the firm, struck a bargain with Howells. This new contract was much like the original: he was to produce a book a year and conduct the famous "Editor's Easy Chair" column monthly. The Harpers were to have first refusal of everything he wrote, but he could publish for extra pay in their Weekly or Bazar or in the ancient North American Review, which Harvey owned personally. Howells did place editorials in the Weekly, major criticism in the North American, and material especially for women in Bazar. He also recruited novelists, among them Edith Wharton, Robert Herrick, Henry B. Fuller, George Ade, and of course Henry James, for a new Harper stable.

Though the fighting realist, social critic, and anti-imperialist tended to appear in the North American and the Weekly, it is not true that pungency deserted "The Editor's Easy Chair" under Howells. The best of his literary criticism and his best poetry appeared in the period 1900-1916. Among the novels of the last decades, The Kentons (1902); The Son of Royal Langbrith (1904); Through the Eye of the Needle (1907), the sequel to his utopian romance; The Leatherwood God (1916); and The Vacation of the Kelwyns (1920) have notably caught the attention of critics in later generations. Questionable Shapes (1903) and Between the Dark and the Daylight (1907) gathered excellent short stories, mainly supernatural, but including "Editha," a favorite choice of classroom anthologies. The travel books of the period, especially London Films (1905), Certain Delightful English Towns (1906), and Seven English Cities (1909), draw present-day interest. My Mark Twain (1910) is a unique literary memoir. The Mother and the Father (1909), with its sinewy blank verse, seems always about to be rediscovered.

With the younger generation he tried to lead into a new realism Howells had bad luck. The best died tragically young, a "generation lost": Frederic in 1898, Crane in 1900, Norris in 1902. He never hit it off with Theodore Dreiser, though Howells put "The Lost Phoebe" into his Great Modern American Stories (1920). A third of the pieces anthologized in that volume were written by women, including some by older friends like Sarah Orne Jewett, Mary Wilkins Freeman, and Alice Brown, and others by newer friends like Edith Wharton, Edith Wyatt, and Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Gilman's "The Yellow Wall Paper" was a special case: Howells had secured its first publication in 1892 and was first to reprint it.

Honors were heaped on Howells as he aged. An evanescent town and a five-cent cigar took his name. He presided over the first meeting of the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1900 and served as its president until 1904. He then became a charter member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and its president for life. He played a leading role in founding the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. The celebration of his seventy-fifth birthday was a national event; President William H. Taft attended. Howells died in New York City. To mainstream America, so far as it cared, he became an icon--required reading in many high schools. And a new professional generation took him as a target for iconoclasm.

In his time Howells was famous for the personality that still shines through his letters and his art. Who else could have been the intimate friend of both Henry James and Mark Twain? Howells charmed women and men with wit, extraordinary verbal facility, kindness, and gentleness. Yet to overlook his mastery of every mode of irony is to overlook Howells. Irony requires plural habits of thought and complex vision. With a deep capacity to suffer, he forged his personality in the fires of inner conflict. His ironies could be delightfully funny; "droll" was a word he loved so well that he used it as a verb. He consciously released aggressions and resentments into critical irony. His dark ironies were deadly, and he knew the power of tragic irony. Nevertheless, to fail to grasp the implications of his self-irony, his self-deprecation, is to lose Howells altogether.

He realized that he might have been a greater artist had he written less. But he could hardly have helped being Howells as he was. The great reputation that declined disastrously during the last decade of his life began to revive at the centennial of his birth in 1937. His name has risen slowly but steadily since. His place in literary and cultural history is established. Editing of his work and his correspondence has become a minor industry.

At the low point of Howells's reputation modernist critics condemned him as "feminine" and "shallow" and "smiling" and "squeamish" to the point of ignoring sexuality. During the second half of the twentieth century, however, revisionist studies challenged such notions, and taste changed over time. The "feminine" came to be seen as a good in itself. "Shallow" Howells disappeared before perception of the serious social and moral critic, a prescient and complex ironist. "Smiling" Howells was set beside a man often conflicted and anguished, with his own sort of tragic vision. In place of the "squeamish" Howells, readers recognized an artist in whose work sexuality, carefully coded, is richly present.

The late twentieth-century essays on Howells by Gore Vidal and John Updike are a milepost. In " 'The Peculiar American Stamp' " (New York Review of Books, 27 Oct. 1983), Vidal characterizes him as "a master of irony" who "wrote a half-dozen of the Republic's best novels" with an "avant-garde realism" in which may be found "a darkness sufficiently sable for even the most lost-and-found of literary generations." In "A Critic at Large: Howells as Anti-Novelist" (New Yorker, 13 July 1987) and "Rereading Indian Summer" (New York Review of Books, 1 Feb. 1990) Updike sees an artist who is not only postmodern, but avant-garde: a natural antinovelist. Where Vidal is struck by Howells's "lapidary" sentences, Updike responds to the "felicity" of the style--as Twain and James did a hundred years before. Updike finds Howells "fascinated and truthful" about sex. Sex in Howells's novels, says Updike, "surfaces in sudden small gestures or objects of fetishistic intensity." Most of all, "today's fiction . . . has turned, with an informal--a minimalist--bluntness, to the areas of domestic morality and sexual politics which interested Howells. . . . Howells' agenda remains our agenda."

Bibliography

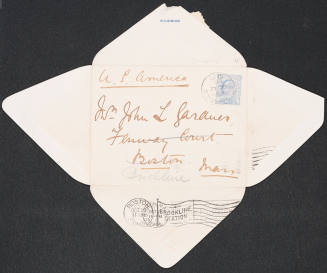

The central collection of Howells's papers is held by the Houghton Library, Harvard, though important collections exist in many places. A Bibliography of William Dean Howells, ed. William M. Gibson and George Arms (1948), marks the beginning of serious Howells studies, and it remains the standard. Also indispensable are the major collections of published letters: Life in Letters of William Dean Howells, ed. Mildred Howells (1928); Mark Twain-Howells Letters, ed. H. N. Smith and Gibson (1960); W. D. Howells: Selected Letters, ed. C. Lohmann et al. (6 vols., 1978-1983); and If Not Literature: Letters of Elinor Mead Howells, ed. Ginette de B. Merrill and Arms (1988). The nineteen volumes thus far published of A Selected Edition of W. D. Howells are important for their editorial materials as well as the texts. Significant other collections of Howells's writings are The Complete Plays of W. D. Howells, ed. Walter J. Meserve (1960); W. D. Howells as Critic, ed. Edwin H. Cady (1973); and The Early Prose Writings of William Dean Howells (1853-1861), ed. Thomas Wortham (1990). Also see Critical Essays on W. D. Howells, 1866-1920, ed. E. H. Cady and Norma W. Cady (1983).

The main biographies are Edwin H. Cady, William Dean Howells: Dean of American Letters (1958); Van Wyck Brooks, Howells: His Life and World (1959); and Kenneth S. Lynn, William Dean Howells: An American Life (1971). Studies mainly focused on the early life include James Woodress, Howells and Italy (1952); Olov Fryckstedt, In Quest of America: A Study of William Dean Howells' Early Development (1958); John W. Crowley, The Black Heart's Truth: The Early Career of W. D. Howells (1985); Cady, Young Howells & John Brown: Episodes in a Radical Education (1985); and Rodney D. Olsen, Dancing in Chains: The Youth of William Dean Howells (1991).

Among the major critical volumes are O. W. Firkins, William Dean Howells: A Study (1924); Everett Carter, Howells and the Age of Realism (1954); George N. Bennett, William Dean Howells: The Development of a Novelist (1959); George C. Carrington, The Immense Complex Drama: The World and Art of the Howells Novel (1966); Kermit Vanderbilt, The Achievement of William Dean Howells (1968); George N. Bennett, The Realism of William Dean Howells, 1889-1920 (1973); and Elizabeth S. Prioleau, The Circle of Eros: Sexuality in the Work of William Dean Howells (1983). The best obituary is by Booth Tarkington, "Mr. Howells," Harper's Monthly, Aug. 1920.

Edwin H. Cady

Back to the top

Citation:

Edwin H. Cady. "Howells, William Dean";

http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-00803.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 15:36:21 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Salem, Indiana, 1838 - 1905, Lake Sunapee, New Hampshire

Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1836 - 1907, Boston

South Berwick, Maine, 1849 - 1909, South Berwick, Maine

Plainfield, Massachusetts, 1829 - 1900, Hartford, Connecticut

Bordentown, New Jersey, 1844 - 1909, New York

Newport, Rhode Island, 1842 - 1901, Phoenix, Arizona

Hartford, Connecticut, 1833 - 1908, New York

Pierrepont, New York, 1859 - 1950, White Plains, New York

Philadelphia, 1855 - 1936, New York