Joseph Pennell

Philadelphia, 1857 - 1926, New York

Pennell, Joseph (4 July 1857-23 Apr. 1926), etcher, lithographer, and illustrator, was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the only child of Larkin Pennell, a shipping clerk, and Rebecca A. Barton. The family came from a long line of Quaker farmers. He left the family farm for a shipping office in Philadelphia, where he spent his early years. Influenced by the work of American artists exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art during the centennial year in 1876, he made an early decision to become an illustrator, much to the disquiet of his parents. Having failed to gain admission to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, he became a clerk at the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Company and attended drawing classes in the evening at the newly founded Pennsylvania School of Industrial Art. He was an industrious student, practicing his drawing during quiet moments at the office. He also studied etching and lithography at the school, under the supervision of the architect Charles Marquedant Burns. Burns's enlightened teaching methods led Pennell to regard him as an early mentor.

During the 1870s Pennell refined his etching technique through his contact with Stephen J. Ferris, an etching enthusiast and skilled technician. Ferris was generous with his knowledge, allowing Pennell to assist him in the studio and observe him at work. In addition, he introduced Pennell to contemporary Spanish art, an early stylistic influence, especially on his illustrative work. By 1880 Pennell had abandoned his clerkship for further study at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, to which he applied again and was accepted; his teachers there included Thomas Eakins. As well as experimenting with etching technique, he pursued his interest in urban subjects. In etchings of Philadelphia like Black Horse Inn Yard (1880; Library of Congress) and Yard of the Plow Inn (1881; Minneapolis Institute of Arts), he favored historic views of the city, an interest he would retain throughout his life. He also established himself in a studio and received his first commission from Scribner's Magazine, celebrated for the quality of its illustration (Apr. 1881). The drawing was followed by others of well-known landmarks like the White House. Pennell's association with the magazine, which became known as The Century Magazine in November 1881, lasted some thirty years and coincided with the golden age of American illustration.

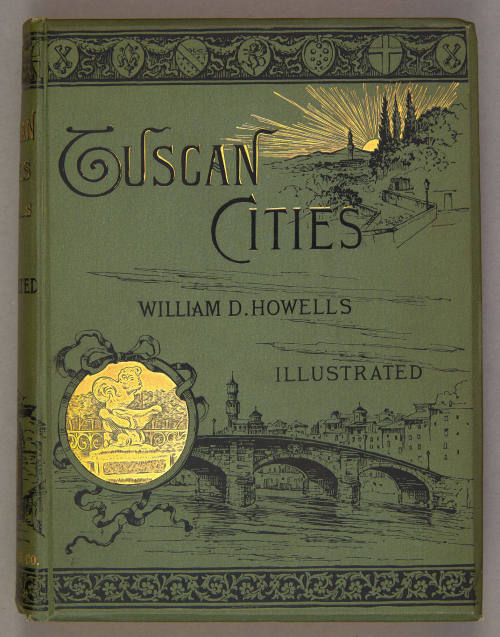

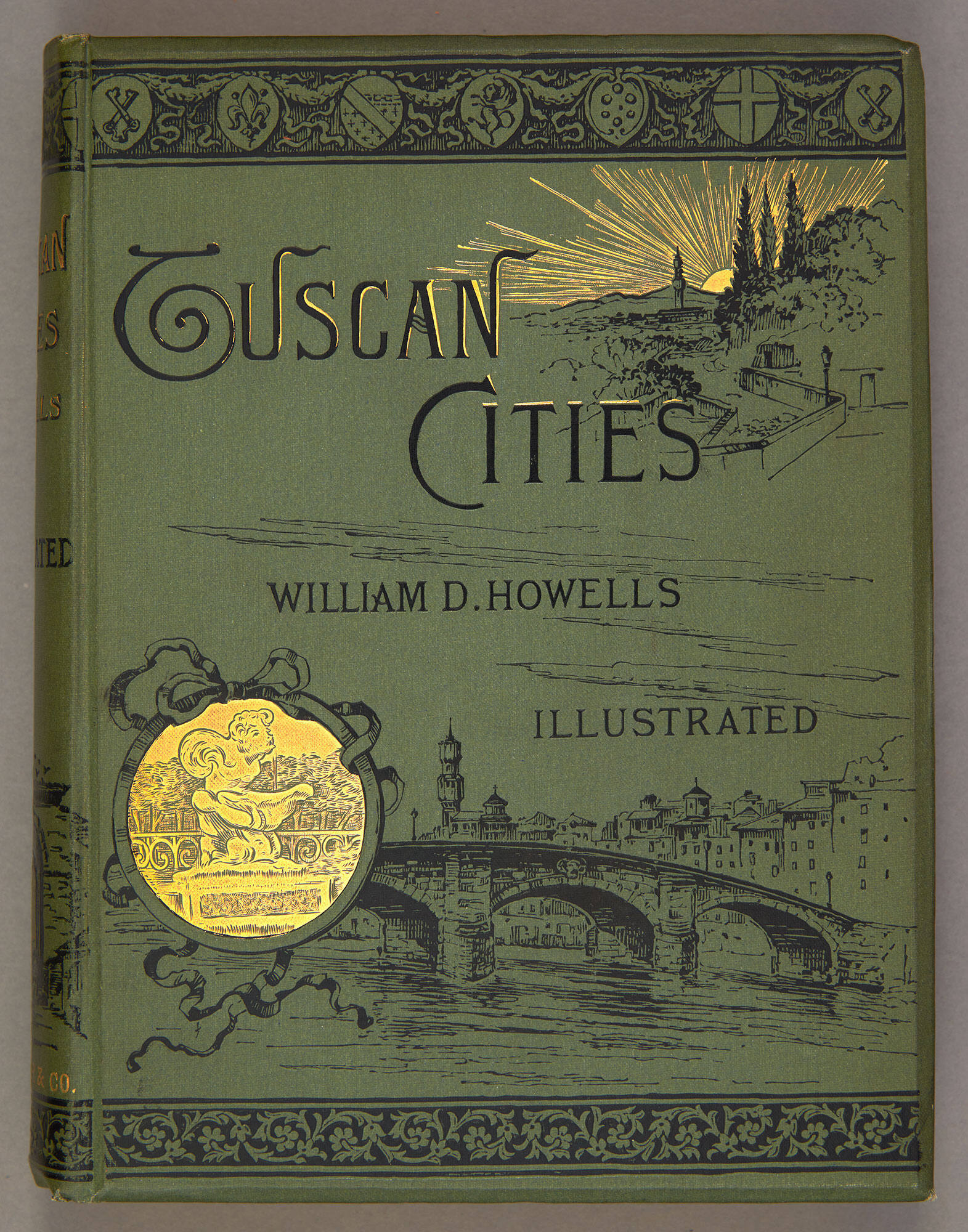

Pennell spent the winter of 1881-2 in New Orleans, Louisiana, working on illustrations for a series of articles on Louisiana and the Creoles by George W. Cable. During his sojourn Pennell encountered Oscar Wilde, whose enthusiasm for the work of James McNeill Whistler fired his budding interest in the artist. Whistler's advocacy of subject matter taken from modern urban life and meticulous craftsmanship appealed to Pennell. The illustrations for Cable became Pennell's first major success and a second commission followed from Scribner's for ten etchings to accompany a series of articles on Tuscan cities by William Dean Howells, published in 1884. The two commissions secured his reputation and pushed him to the forefront of the burgeoning etching movement in America. From 1883 onward, he was a regular exhibitor at the New York Etching Club. An invitation followed from the publishing firm, Cassell's, to contribute to a series of etchings by contemporary artists. By 1883 Pennell had been elected to both the Pennsylvania Academy Art Club and the newly formed Philadelphia Society of Etchers.

Pennell made his first visit to Europe in 1883 when, armed with his Scribner's commission, he left for Italy. His taste was for the picturesque crumbling old quarters of towns like Pisa, Siena, and Florence. His interest lay in portraying undiscovered lanes, doorways, and vistas. His Ponte Vecchio (1883; Library of Congress) was a departure from conventional tourist views of the city of Florence. Pennell's concern was to create a vivid contrast between light and shade, using crisp, delicate lines to indicate details that stirred his interest, as in Ponte San Trinita, Florence (1883; Library of Congress). His reputation was further enhanced by journeys to Scotland, England, and Ireland. In England he chronicled a tricycle ride from Coventry to Chester in an illustrated article for the Century (Sept. 1884). The article launched his career as a travel writer-illustrator. His travels took him all over the world, to places as far apart as the Scottish Hebrides and Greece. He traveled mostly by bicycle and later by motorcycle.

In 1884 Pennell married Elizabeth Robins. Shortly after their marriage, they left for England to work on illustrations of English cathedrals and of the London suburb of Chelsea; they decided to make London their permanent home. They collaborated on numerous works on travel and art, including A Canterbury Pilgrimage (1885), Italy from a Tricycle (1885), An Italian Pilgrimage (1887), and Lithography and Lithographers (1915). They worked incessantly on their travels, sometimes on several commissions at once. The etching Doorway, Venice (1884; Library of Congress) documents this period. Frank Duveneck, an American artist living in Venice, later became Pennell's regular companion on etching expeditions around London.

In London, Pennell's connections at the Century gave him access to artistic and literary circles. He associated with leading figures of the day, including Henry James and John Singer Sargent. Other acquaintances included the surgeon-etcher Francis Seymour Haden and Philip Gilbert Hamerton. He also followed the socialist activities of William Morris and George Bernard Shaw. Pennell never committed himself to any one ideological cause, however, although he was an active member of the British National Liberal Club. Cycling became a serious passion. He promoted the interests of the sport through his involvement with cycling organizations like the British Cyclist Touring Club and contributed to the popular magazine, Bicycling World.

In 1888 Pennell succeeded Shaw as art critic of the Star newspaper. He joined a band of outspoken so-called New Critics of the 1880s and 1890s who challenged the artistic orthodoxies of the day. He became a vocal critic of the Royal Academy, the most powerful artistic institution in Britain and perennially under fire for its restrictive exhibition policies. Pennell's irascible temperament and uncompromising views on art often antagonized others, although it was said that in private his manner was more congenial. Pennell's publisher remarked that "Mr Pennell had his own ideas about everything . . . When dining in his company, it was interesting to observe the effect of his frank criticisms on people who did not know him well" (Grafly, pp. 371-72). He traveled constantly--to Hungary in pursuit of gypsy subjects and to France on a commission to portray French cathedrals. He also portrayed subjects closer to home in the Whistler-inspired etching Smithfield Market (1887; Library of Congress), part of the Easter Set of etchings published in 1894. During the 1890s, Pennell turned his attention increasingly to pen and ink, rather than etching, due to its particular suitability for modern methods of reproduction. He wrote on the subject in Pen Drawing and Pen Draughtsmen (1889). As a prolific illustrator, he was keenly interested in reproductive processes and diligent in his efforts to show others how these might be best applied to art.

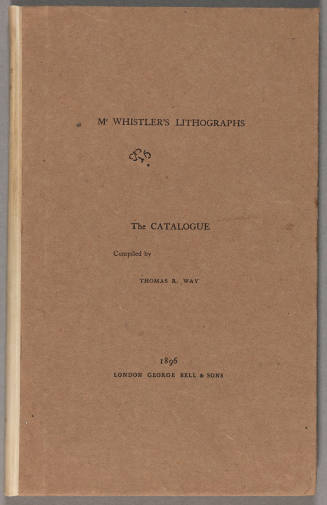

Pennell's friendship with Whistler was an important aspect of his career from this period onward. He and his wife became Whistler's most devoted admirers and later his biographers with their The Life of James McNeill Whistler (1908). They also wrote several other books about Whistler. Pennell's journalism and his appointment as art editor of the Daily Chronicle in 1895 provided a ready-made opportunity to champion the work of talented artist-illustrators like Aubrey Beardsley and Charles Keene. Although this appointment was short lived, Pennell went on to become associated with key British illustrated magazines of the 1890s, including the Yellow Book, the Savoy and the Butterfly. Pennell contributed the etching Le Puy (1894; Library of Congress) to the first volume of the Yellow Book in 1894. He also became a leading member of the Senefelder Club, a body dedicated to the revival of artistic lithography.

In addition to his picturesque depictions of landscape and architecture, Pennell's graphic work during his mature career chronicled the industrial landscape of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. From about 1908 onward, he portrayed the furnaces and smoking chimneys of British and American industrial towns like Sheffield and Pittsburgh. He also embarked upon a series of etchings of West Coast cities, including San Francisco. The new urban skyline of Chicago and New York with its ever taller skyscrapers became another major obsession during this period. In the skyscrapers of New York, portrayed in New York from Brooklyn Bridge (1908; Cleveland Museum of Art), Pennell saw echoes of the Italian towers and cathedrals he had recorded many years earlier. Pennell's concern was to show the impact of human activity upon the landscape. To Pennell, the soft, grainy, atmospheric effects that could be obtained through lithography provided an admirable means of portraying these industrial subjects. His experiments in lithography also encouraged a shift in artistic direction. The crisp, linear approach he had taken to drawing in his earlier work gave way to an emphasis on creating broad areas of tone. In 1912 a series of lithographs, including The Gates of Pedro Miguel Lock (1912; Library of Congress), recorded the construction of the Panama Canal. " 'I went because I believed that at the Canal I should see the Wonder of Work, the picturesqueness of labour, realized on the grandest scale,' " Pennell later declared in response. The occasion also inspired his portrayals of wartime European and American munitions factories during World War I, including the lithograph Furnaces at Night (1916; Library of Congress). By 1917, depressed by wartime Europe, he returned to America for good. Numerous honors came his way, including membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1921. From 1922 to 1926, he taught at the Art Students League in New York. Having absorbed Whistler's working methods during the 1890s, Pennell sought with characteristic rigor to pass on his legacy to future generations of students. Still working ceaselessly and active in public life until the end, he died in Brooklyn, New York. Throughout his career, Pennell played an instrumental role in increasing appreciation of the art of the print. In contrast to the accepted view of etching and lithography as little more than reproductive processes, Pennell believed that the two media were worthwhile methods of artistic expression in their own right. Inspired by the master printmaker Whistler, he worked tirelessly to increase the status of etching and lithography through teaching and writing. He promoted the highest standards of craftsmanship toward this objective through regular contributions to newspapers and periodicals. Through his work as an illustrator, he popularized the idea of the illustrated travel adventure. He illustrated the works of many celebrated authors of the period, including Henry James and William Dean Howells. Historical architecture interested him keenly. Like his compatriot, the etcher Otto Bacher, he traveled extensively around Europe, recording picturesque views of its towns and cities. In addition, Pennell left behind him a remarkable chronicle of the ever-changing cityscape of early twentieth century America.

During his lifetime Pennell enjoyed an international reputation in the graphic arts. He inspired a new generation of twentieth-century American printmakers through his wide-ranging artistic contacts in America and Europe. Together with his wife, he took numerous practical steps to encourage the printmaker's art, establishing a bequest at the Library of Congress to fund the purchase of prints by living Americans. As an illustrator, his openness to technical innovation and contributions to American illustrated magazines mark him as an important figure in American illustration during the late nineteenth century; nevertheless, the extent of his artistic originality remains a matter of debate. Pennell might best be regarded as a minor master of printmaking, but a major figure in the development of the graphic arts in America, who was among the first to be inspired by the new urban skyline of American cities.

Bibliography

The most comprehensive collections of Pennell's work, including prints, drawings, and pastels, are in the Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress. Pennell is also represented in other public collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City; the New York Public Library; the Corcoran Gallery of Art and the National Museum of American Art, Washington, D.C.; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Mass.; the Art Institute of Chicago; the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, Philadelphia; and the Cleveland Museum of Art. The Manuscripts Division of the Library of Congress has extensive archival information about Pennell, including correspondence, press clippings, and other material related to his career. See also the Archives of American Art, Washington, D.C.

An autobiographical account of Pennell's career is Adventures of an Illustrator (1925). The standard biographical source is Elizabeth Robins Pennell, The Life and Letters of Joseph Pennell (1930); see also Dorothy Grafly, "A Pennell Memorial Meeting, Philadelphia, May 18," American Magazine 17 (1926). For information about his published work, see Victor Egbert, A Checklist of Books and Contributions to Books by Joseph and Elizabeth Robins Pennell (1945); for his etched work, see Louis A. Wuerth, Catalogue of the Etchings of Joseph Pennell (1928); For critical discussion of Pennell, see "The Constant Advocacy of Joseph Pennell, Dean of American Printmakers," in James Watrous, American Printmaking: A Century of American Printmaking, 1880-1980 (1984). Pennell's lithographic work is discussed in Clinton Adams, "The Imperious Mr. Pennell and the Implacable Mr. Brown," in Aspects of American Printmaking, 1800-1950, ed. James F. O'Gorman (1988). The exhibition catalog The Pannell Legacy: Two Centuries of Printmaking (1983-1984) highlights the rich resources of the Pennell Collection at the Library of Congress. See also Anne Cannon Palumbo, "Joseph Pennell and the Landscape of Change" (Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Maryland, 1982).

Patricia de Montfort

Back to the top

Citation:

Patricia de Montfort. "Pennell, Joseph";

http://www.anb.org/articles/17/17-00667.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Tue Aug 06 2013 12:33:27 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Philadelphia, 1855 - 1936, New York

Surbiton, Surrey, 1863 - 1920, London

1833 - 1916, Franklin, Massachusetts