Bernard Berenson

Butrimonys, Lithuania, 1865 - 1959, Florence

Intent on becoming a writer and novelist, Berenson set off for Europe in June 1887 for what was to be a one-year trip funded by several people who later sought his advice on art matters, including Isabella Stewart Gardner, Edward Warren, and James Burke. During his extended sojourn Berenson studied Italian Renaissance paintings throughout Europe's museums, galleries, and churches and started accumulating a monumental collection of photographs of Renaissance paintings.

While in Europe, Berenson read Giovanni Morelli's writings on Italian Renaissance art in which Morelli reattributed paintings, using his "scientific" method. According to Morelli, analytic observation of human figures in paintings revealed characteristics that could be used to authenticate works based on artists' styles. After meeting Morelli in May 1890, Berenson divined his new calling to a friend: "We shall give ourselves up to learning, to distinguish between the authentic works of an Italian painter of the 15th or 16th century, and those commonly ascribed to him."

While in England in August 1890, Berenson spent time with art historian and women's advocate Mary Costelloe, who hailed from Pennsylvania and who would eventually become his wife and professional cocontributor. A year later Mary left her husband, Irish barrister Frank Costelloe, and her two daughters to accompany Berenson on his travels.

Berenson's first book, The Venetian Painters of the Renaissance (1894), traced the development of Venetian art between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries. The publication resulted from substantial reworking of one of Mary Costelloe's essays. Her detailed notes from their trips formed the index of Venetian painting, which comprised almost half the book. Generally well received, the publication established Berenson's reputation in Europe and America as an authority on the period.

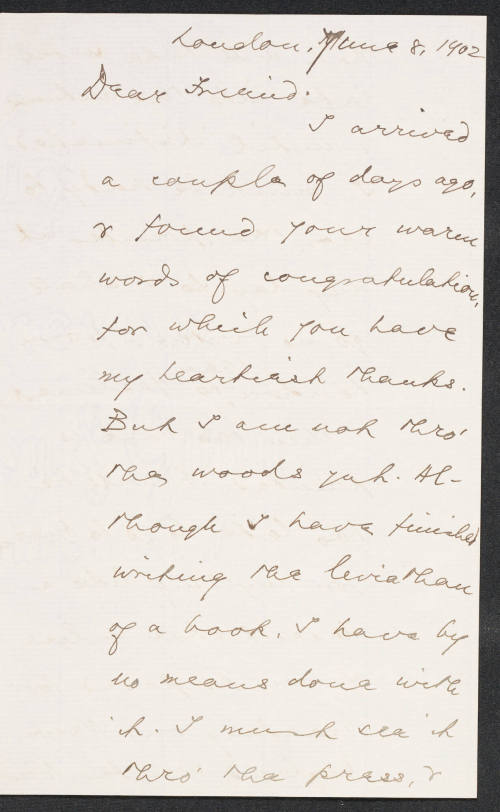

Berenson defined his connoisseurial principles, stemming from Morelli's theories, in his 1894 essay, "The Rudiments of Connoisseurship (A Fragment)," anthologized in The Study and Criticism of Italian Art, Second Series (1902). He wrote that by subjecting a painting to a battery of "tests" used to identify similar traits in specific properties, such as eyes, hands, landscapes, and fabric folds, one could identify a painting's creator by comparing other works by the same painter. Berenson's devaluation of documentation in ascertaining authorship was his most controversial assertion. Using this "scientific" method of morphological analysis, Berenson examined the work of a relatively unknown Venetian painter in Lorenzo Lotto: An Essay in Constructive Art Criticism (1894).

Berenson's first foray into art consultation was locating and acquiring several impressionist works and one Renaissance painting for Burke in 1892. In 1893 a group of American collectors in Rome engaged Berenson's expertise on several paintings. By 1894 Berenson's advisory career was gaining momentum as he began a long-term relationship with American financier Theodore M. Davis.

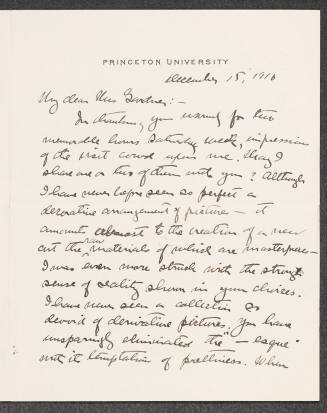

In June 1894 Isabella Stewart Gardner embarked on a yearlong European trip, during which she and Berenson began a collaboration that lasted for thirty years, until her death. For a percentage fee Berenson located Renaissance paintings and negotiated their prices on Gardner's behalf. Gardner's aspirations to assemble the finest art collection in Boston encouraged Berenson to acquire many masterpieces that formed the nucleus of her private museum.

Published in 1896, Berenson's The Florentine Painters of the Renaissance surveyed artists from the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries and introduced his theory of "ideated sensations." The Florentine artists, wrote Berenson, excelled in conveying tactile values and movement in two-dimensional representation, thus affording the viewer a unique visceral experience. Thus, a painting's formal elements should evoke life-enhancing responses from their viewers. Likewise, Berenson concluded that the artists he examined in The Central Italian Painters of the Renaissance (1897) specialized in illustration and "space composition," or the ability to compose a viable sense of depth within a two-dimensional construction.

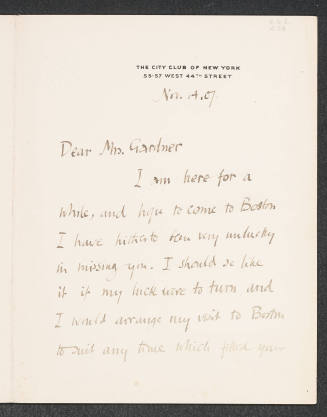

The North Italian Painters of the Renaissance (1907) was the final book in his "four gospels" on Italian painters and was his hardest to complete because this selection of artists' works did not fit his theories of ideated sensations. He focused instead on the dangers of "prettiness" and the lack of life-enhancing qualities. In all of the subsequent editions of the four surveys, Berenson never altered his text. He did, however, spend the rest of his life correcting and supplementing the extensive lists of attributions at the end of each book.

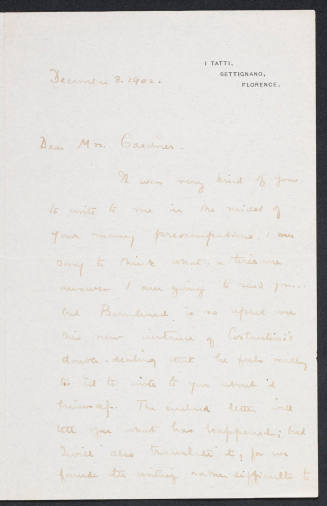

After Costelloe's husband died in 1899, she and Berenson married in 1900 and settled into "Villa I Tatti," a house built in the sixteenth century just outside Florence. The Berensons, who had no children together, kept the villa for the rest of their lives, regularly entertaining American expatriates and scholars, such as Edith Wharton and Henry James, as well as European artists and writers, including Oscar Wilde and Berenson's brother-in-law Bertrand Russell. Berenson bequeathed the three-story house and his vast collection of photographs and books to Harvard University, which runs a fellowship and study program at this center for Italian Renaissance studies.

Berenson's greatest art historical contribution was published in 1903: The Drawings of the Florentine Painters: Classified, Criticised, and Studied as Documents in the History and Appreciation of Tuscan Art with a Copious Catalogue Raisonné. The two-volume book was widely praised for its extensive text and 180 plates of many previously unpublished drawings that shed new light on the development of these Renaissance painters. It also confirmed Berenson's reputation as an extremely thorough and knowledgeable connoisseur, for he had visited eighty museums and seventy private collections in Europe to gather his material.

Also in 1903, the Berensons traveled to the United States, where they met several important collectors, including Henry Walters in Baltimore and Peter Widener and John Graver Johnson in Philadelphia, all of whom enlisted Berenson's advisory services to enhance their collections. Berenson later wrote catalogs of Widener's and Johnson's collections (published in 1913 and 1916, respectively).

The nature of the art trade and Berenson's close association with it drew suspicion in some art historical circles. Since Berenson was paid by commissions, the more paintings he attributed to masters, the more he profited. His standard commission was 10 percent, but he sometimes took as much as one-third to one-half of the net. Berenson once sold a Pinturicchio Madonna from his own collection to Gardner at a large profit. In 1905 the Metropolitan Museum of Art bought an El Greco on Berenson's advice, unaware until afterward that he received £1,700 for the sale. He was occasionally involved in smuggling out of Italy works headed for America.

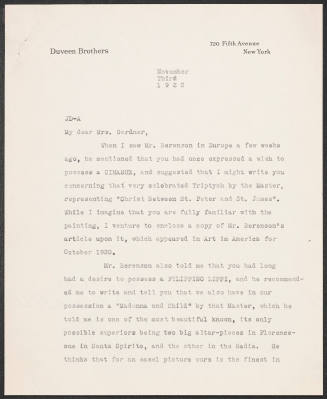

Although Berenson worked with numerous dealers throughout his lifetime, none was more notorious than Joseph Duveen. After meeting Berenson in 1906, the dealer sought the expert's imprimatur for myriad sales over the next thirty years. A formal arrangement cloaked in secrecy was initiated in 1912, with Berenson receiving 25 percent of net profits. With Berenson's attributions, often sent by wire using code names, Duveen sold many masterpieces to American collectors, including John Pierpont Morgan and Andrew Mellon. Duveen's questionable transactions (the firm had paid the U.S. Customs Service $1.8 million to settle a customs claim in 1911), bullish behavior, incessant inquiries, and disagreement over Berenson's attributions eventually led Berenson to terminate the partnership in 1937.

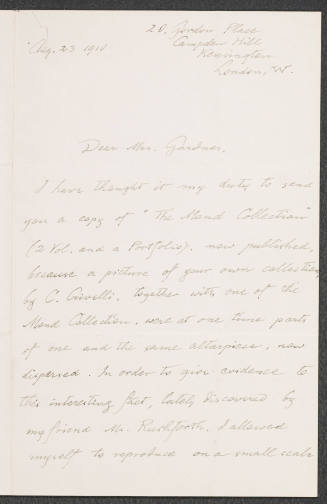

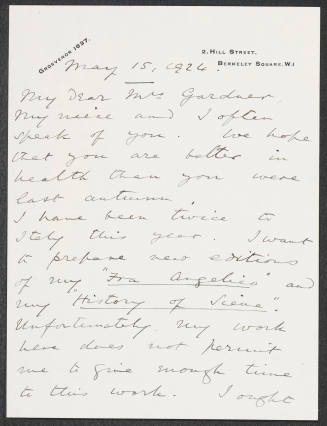

Berenson's later scholarly writings, none of which had as much impact as his four "gospels," included Venetian Painting in America (1916), The Study and Criticism of Italian Art, Third Series (1916), Essays in the Study of Sienese Painting (1918), and Studies in Medieval Painting (1930), as well as books on artists Stefano di Giovanni Sassetta (1909), Alberto Sani (1950), Caravaggio (1953), and Piero della Francesca (1954). His Aesthetics and History in the Visual Arts (1948) expanded on his theories of ideated sensations and "life-enhancing" qualities in art. He was one of six contributing writers to the inaugural issue (Jan. 1913) of Art in America, a magazine subsidized by Duveen to educate American collectors.

Berenson remained in Europe during both world wars. At the recommendation of his friend Edith Wharton, Berenson was employed as a translator and negotiator to the American Army Intelligence Section during World War I. Because of his Jewish heritage and anti-Fascist beliefs, Berenson was hidden by friends just north of I Tatti during World War II. His diary entries written during his exile were published in 1952 as Rumour and Reflection, 1941-1944.

Until his death Berenson continued consulting, primarily for dealer George Wildenstein, and writing. He regularly published articles in the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera, and he wrote several books on art theory that were not well received critically, in part because he lambasted modern art trends. He died in Florence, Italy.

Among Berenson's greatest contributions to the field of art were his Italian Renaissance scholarship and his impact on American public and private collections (he once boasted that most Italian paintings had come to America with "my visa on their passport"). He mentored many American art historians, including John Walker and Sydney J. Freedberg, who studied at I Tatti and worked at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., as director and chief curator, respectively. Despite his vehement disdain for modern art, Berenson's formalist rather than contextual approach to art interpretation anticipated modern reductionist aesthetics propounded by formalist critics such as Clive Bell, Roger Fry, and Clement Greenberg.

Bibliography

Much of Berenson's correspondence remains at the Berenson Archive, Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, Villa I Tatti, Florence. Berenson's early books on the four regions of Italian Renaissance art were combined into one volume in 1930 titled Italian Painters of the Renaissance. The three-part series The Study and Criticism of Italian Art presents several of his early articles. Bibliografia di Bernard Berenson, comp. William Mostyn-Owen (1955), lists his writings complete to that date (see Samuels for additional materials). The most thorough Berenson biography is Ernest Samuels, Bernard Berenson: The Making of a Connoisseur (1979) and Bernard Berenson: The Making of a Legend (1987). Other biographic sources include Berenson's autobiography, Sketch for a Self-Portrait (1949), and Forty Years with Berenson (1966), written by his companion Elisabetta "Nicky" Mariano. See Mary Berenson: A Self-Portrait from Her Letters and Diaries, ed. Barbara Strachey and Jayne Samuels (1983), for Berenson's wife's contributions to his career; Colin Simpson, Artful Partners: Bernard Berenson and Joseph Duveen (1986), on the relationship between the art expert and the dealer; and Mary Ann Calo, Bernard Berenson and the Twentieth Century (1994), on Berenson's interest and influence on modern art and aesthetics. An obituary is in the New York Times, 8 Oct. 1959.

N. Elizabeth Schlatter

Citation:

N. Elizabeth Schlatter. "Berenson, Bernard";

http://www.anb.org/articles/17/17-00066.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 10:30:20 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated4/2/25

Germantown, Pennsylvania, 1864 - 1945, Florence

Northamptonshire, 1851 - 1924, Oxford

Deep River, Connecticut, 1868 - 1953, Princeton, New Jersey

Lavenham, United Kingdom, 1864 - 1951, Fiesole, Italy

Vilna, 1868 - 1954, Santa Barbara, California

Château Saint-Leonard, France, 1856 - 1935, Florence

near Treviso, about 1459 - 1517, Conegliano or Venice